Twenty years ago, as Director of Resident Education for the Department of Ophthalmology of a midwestern medical school, I was given a new task: transform our training program from structure-based to competency-based. There had been a sea change in medical education. Up until then, our residents spent a prescribed time in certain areas of ophthalmology. It was assumed each resident would learn what they needed in that time bloc. There were evaluations of progress in the residency program and a written and oral examination to become board-certified, but the training was all based on the time spent on the subject.

All that changed when a system of expected Clinical Competencies was proposed and enforced. In February 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) endorsed six general Clinical Competencies that all training programs would use in their teaching and evaluation:

- Patient Care

- Medical Knowledge

- Professionalism

- Systems-based Practice

- Practice-based Learning

- Interpersonal and Communication Skills

It was a monumental task. We had to identify how we designed and tested our curriculum to respond to each of these areas. Although this represented a significant improvement over the structure-based curriculum of the past, it was not without its problems. Basically, it looked backward, testing how well an individual physician would respond to what he or she had been exposed to in their training. The problem became apparent on September 25, 2014 in Dallas, Texas.

Thomas Eric Duncan arrived at Texas Health Presbyterian Dallas and was sent home with the diagnosis of sinusitis. Unfortunately, the real diagnosis was Ebola. Although it was a constellation of errors that moved this from hazard to catastrophe (The “Swiss Cheese” model of James Reason), in more general terms it showed that mere competency did not ensure capability.

Capability looks forward, not merely backward. It is the ability to utilize past learning to solve future problems. In Complexity Theory terms, it allows an individual to deal with the Unknown Unknowns of the Complex Domain in The Cynefin Framework of Snowden and Boone. In this framework, a number of items are used to determine the domains in which the situation occurs: Simple, Complicated, Complex, Chaotic, or Unknown. One such test is the relationship of cause and effect.

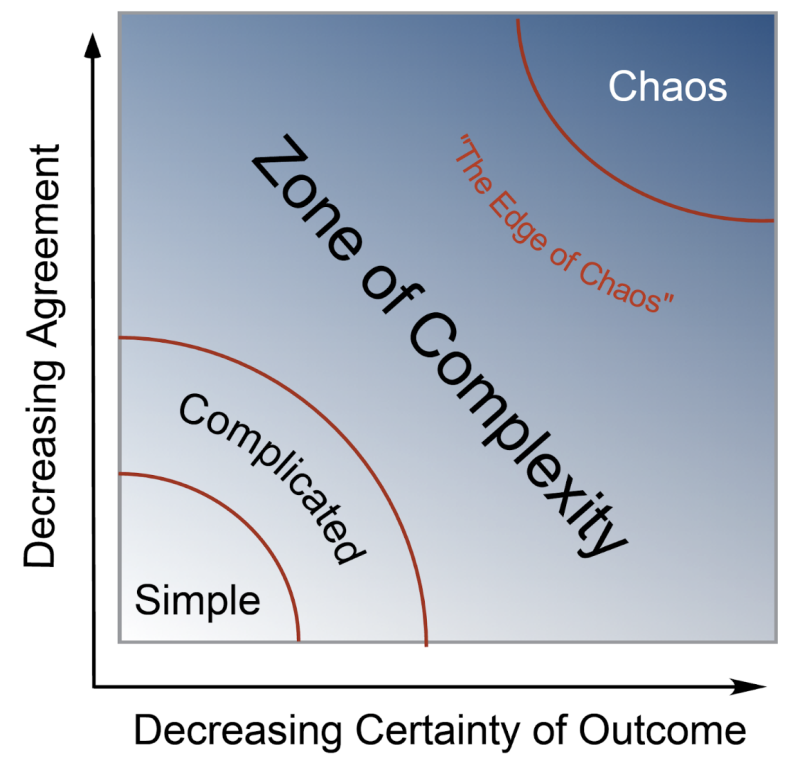

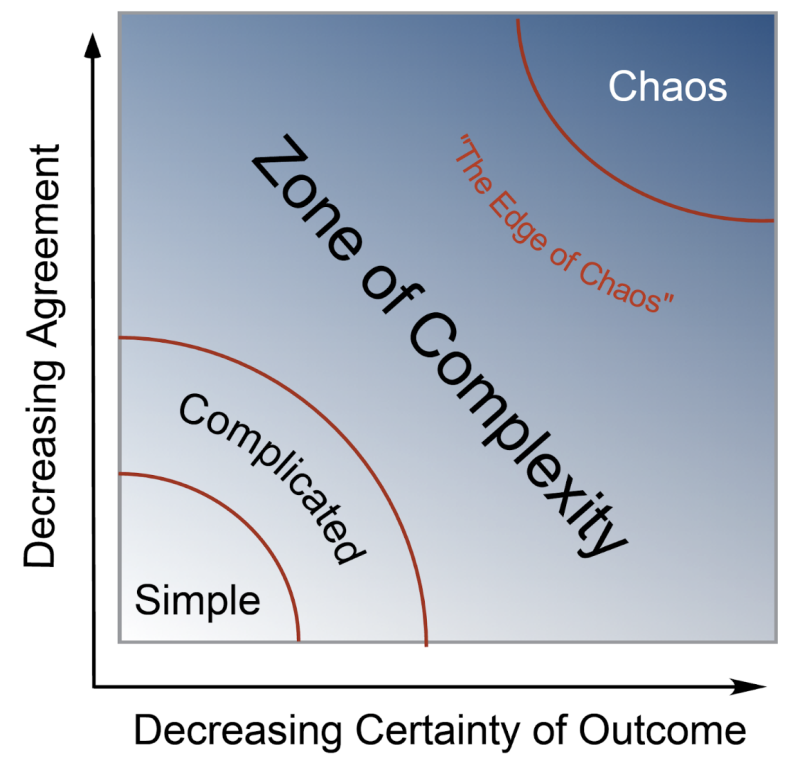

In the Simple Domain, everybody can see the relationship. In the Complicated Domain, only experts can see it. In the Chaotic Domain, cause and effect are no longer related. In the Complex Domain, they are still related, but the relationship can only be appreciated in retrospect: so-called retrospective coherence. Imagine a Sudoku puzzle. It can be challenging to work through to the answer but after the puzzle is completed, it can be checked in seconds. Another test is the Stacey Diagram where Degree of Agreement and Certainty of Outcome are graphed in a two-dimensional plot (adapted from Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. Edgeware: Lessons from Complexity Science for Healthcare Leaders. Irving, TX: VHA Press; 2008; 136–143.):

In 1955, Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham described this as the bottom right pane in the Johari Window in a play on their first names. This is the area in which the individual ventures into the unknown, and experts are of little help because it is unknown to them as well. Scary, but the situation is by no means hopeless! It does require a different set of tools, however. The predictability horizon is short and the relationship between cause and effect will not be understood until the ultimate arrival at the solution. Multiple safe-fail actions (as opposed to one fail-safe plan) are needed. In short, Capability is needed!

In Capability for Complex Systems: Beyond Competence, Stewart Hase and Boon Hou Tay discuss the origins of the “Capability Movement” in the 1980s as a way for industry in the United Kingdom to compete in a shrinking marketplace. Competency was the minimum standard to deal with linear, rational systems. However, success in the Complex Domain, the “unknown unknown” pane in the Johari Window, necessitates a new toolset. Capability becomes an essential component.

In order to develop capability, two components are required: 1) commitment to lifelong learning; and 2) willingness to utilize action research. That action research entails performing the multiple safe-fail pilot projects described by Snowden and Boone and the Little Bets of Peter Sims.

This is precisely what was done with Covid by such visionaries as Derwand, Scholz, and Zelenko, McCullough, Alexander, Armstrong, et al, Tyson and Fareed, Kory, Meduri, Varon, et al and others. It is unfortunate that it appears a concerted effort was directed at cloaking the widespread dissemination of this information. Many lives might otherwise have been saved. Someday, the true scope of the damage done by not recognizing Covid as occurring in the Complex Domain will be recognized.

AI has been touted by many as the salvation of modern medicine. This has resulted in a plethora of articles on the subject. Some of this is from organizations that may have a substantial financial interest in the widespread adoption of this modality. There is no doubt that AI will play a major role in healthcare in the future, but it is important that the true utility, as well as limitations, be understood, not only by healthcare professionals but also by patients. Particularly disturbing is the increasing ability of AI to deceive humans.

I served as the Secretary of Education for the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. We were responsible for oversight of all of the training programs in the United States and Canada. Over decades, we had developed a robust curriculum and expectation of education of the trainees in our programs. They were required to write an accepted thesis and pass a written and an oral exam in order to be awarded Fellowship in the Society.

By the time the fellow applicants reached the stage of the oral exam, they pretty much had been judged to be competent. When I gave an oral exam, I was just looking for that very rare individual who somehow had not developed a sense of responsibility – someone who might be dangerous. I would ask questions about several topics, finally getting to those that really did not have an answer. Either they were beyond the experience of the examinee or were questions that remained unsettled. I wanted the examinee to say, “I don’t know” and then I would probe them on what they would do next. This was in the days when I had not yet understood the difference between merely complicated and truly complex. One person whom I failed (he may actually be the only one) was someone who insisted he knew an answer to a problem that was unanswerable at that time.

It concerns me that AI could perform in the same way but on a massive scale. If it does not know the answer it will “fake it.”

Melanie Mitchell and David Krakauer of the Santa Fe Institute are true experts in AI. They describe AI as more like an extensive library than an entity with true intelligence. AI lacks an understanding of context. I think it was Melanie who said: It may be able to beat you at chess but would fail preschool.

Mark Quirk, Trisha Greenhalgh, Malcolm Gladwell, and Daniel Kahneman all describe the interplay between metacognition and intuition, though they may call it by slightly different names. Metacognition and “evidence-based” may work very well in the merely complicated domain, but intuition or “thinking fast” may play a role when the problem is truly complex. To further muddy the waters, part of the problem may be complicated or even simple, and part complex. The difficulty is in sorting out which tools are needed and when to use them.

It is clear that medicine, like academia, politics, and business, failed society in “The Great Ethical Collapse” of the past four years. We will be sorting out the reasons for this for quite some time, but high on the list will be a complete failure of leadership in all of these areas. The article by Leonard J. Markus and Eric J. McNulty of the T. H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard gets it partly right in citing the need for leaders ready to embrace complexity, make tough decisions amidst great ambiguity, and prioritize personal and organizational resilience. However the authors failed to address the inadequacies of the leadership models of the past, and the fact that virtually all of the current leaders, at least in healthcare, were never trained in the approach they recommend! Will it be possible for them to somehow “throw the switch” and now do the right thing?

In order to make a substantive change in the way medicine and public health are practiced, medical and public health education must be fundamentally reformed. This is the same reasoning of the Flexner Report of 1910. Although subject to a fair amount of revisionist thinking, there is no doubt that this report drastically altered medical education, aligning it with the university model of Europe. It allowed tremendous improvement in dealing with the complicated problems of infectious disease but at the expense of the complex problems of chronic disease. It transformed medicine from improving health to treating disease.

The new reforms must ensure that entry into, and advancement within, the healthcare professions recognize that, while the facility in the STEM subjects is necessary, it is far from sufficient to prevent the disaster of the past four years. Critical thinking, courage, ethics, and moral responsibility must be valued just as highly. Formal training in leadership must also be instituted. Healthcare professionals must see themselves as leaders of patients and not mere treaters of disease. This is far too much to be compressed into the 4 years of professional school and must be started early, preferably in secondary or even middle school.

It is ironic that this problem was already addressed nearly a quarter century ago in the British Medical Journal. In the last of a four-part series on Complexity in Healthcare, Sarah Frazer and Trisha Greenhalgh describe the changes needed in medical education in order to bring about the needed focus on capability. There is so much packed into this article that it is impossible to reproduce it all. This is but a taste:

“Checklist driven” approaches to clinical care, such as critical appraisal, clinical guidelines, care pathways, and so on, are important and undoubtedly save lives. But what often goes unnoticed is that such approaches are useful only once the problem has been understood. For the practitioner to be able to make sense of problems in the first place requires intuition and imagination—both attributes in which humans, reassuringly, still have the edge over the computer.21 Education that makes use of the insights from complex systems helps to build on these distinctly human capabilities…

Adults need to know why they need to learn something and they learn best when the topic is of immediate value and relevance.23 This is particularly true in changing contexts where capability involves the individual’s ability to solve problems—to appraise the situation as a whole, prioritise issues, and then integrate and make sense of many different sources of data to arrive at a solution. Problem solving in a complex environment therefore involves cognitive processes similar to creative behaviour.24 These observations are directly opposed to current approaches in continuing education for health professionals, where the predominant focus is on planned, formal events, with tightly defined, content oriented learning objectives.

Are there any indications that this change in direction for medical education is worthwhile? Fortunately, there are. In two widely separate locations, a focus on fostering capability made a significant and measurable difference. Qulturum, an innovative approach to emphasizing capability in Jönköping, Sweden, has significantly elevated the quality of healthcare across a number of parameters. The NUKA system of care has done the same thing for the Southcentral Foundation in Alaska, winning 2 highly prestigious Baldrige Awards for quality.

This will be a monumental challenge, as those who have spent a professional lifetime climbing to the pinnacle of their profession will not go quietly. But the experience of both of these organizations proves it can be done, and the results are amazing.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.