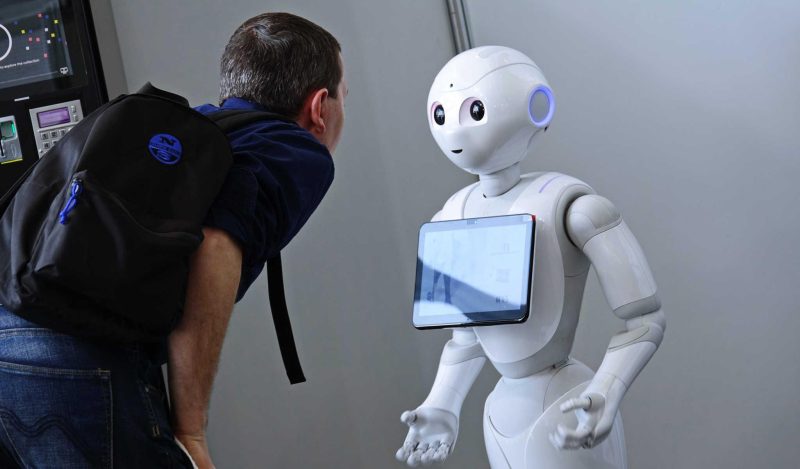

The expression “artificial intelligence” seems fitting for any entity that does not take responsibility for its words. ChatGPT and the like remind us that machines are not human beings and human beings are not machines. Machines do not approve and disapprove as human being do. Machines do not have sentiments. They do not have a conscience. They do not have moral responsibility.

We do.

Our moral responsibility extends to all of our conduct, including our discourse.

Our discourse flows from our thoughts. Thinking, too, can be regarded as a form of conduct. Even when alone, when you think, words emerge.

Our moral responsibility, therefore, extends to picking our words to communicate our meaning. “There are certain terms in every language,” wrote David Hume, “which import blame, and others praise; and all men, who use the same tongue, must agree in their application of them.”

Here I invite you to pick your pejoratives. If we pick our pejoratives alike, then we “use the same tongue,” as Hume puts it.

First, a few words to justify the rumination: By thinking about whether disapproval is built into a word, we see whether our words necessarily express a sentiment. If they do express a sentiment, our words may oblige us to justify the sentiment. Readers may be happy to enter into your sentiment. But sometimes the sentiment is itself up for debate.

By seeing disapproval more clearly, we see more clearly what exactly it is that we disapprove of. Is it lobbyists we disapprove of, or is it only certain privileges that certain lobbyists seek? Are there good lobbyists as well as bad? How about good rent-seekers?

Also, this rumination may help you realize how pervasively disapproval suffuses your discourse, even if communicated only by implication or connotation rather than denotation. Even if you give something a grade of A+, you select that object for approval, as compared to salient contrary or opposing objects. Since you evaluate constantly, it is good to see clearly where and how you evaluate.

Certain words are freighted with a negative connotation or valence. But the issue is not about how you hear others using a word. It is about how you use the word.

The question to ask yourself is: “When I use the word, do I build in disapproval, necessarily?”

Put another way: “As a word in my active vocabulary, is that word necessarily pejorative?”

In what follows I consider only nouns.

Some words, clearly, are used with disapproval built-in, such as:

balderdash

baseness

bigotry

blemish

defect

degeneracy

error

flaw

folly

fool

mistake

vice

It would be odd to hear someone use any of those words while approving of the thing signified by the word. The oddness might be humorous. I think of a saying of the famed movie mogul Samuel Goldman: “We need some new clichés!”

And some words have neither approval nor disapproval built-in:

belief

opinion

judgment

practice

tradition

custom

Sometimes it is just a question of how the word is used. Consider the word corruption. That might seem to belong on the necessarily-pejorative list. But bribery is called corruption, and sometimes bribery is praiseworthy. Consider the film Schindler’s List. The protagonist, Oskar Schindler, bribed government officials to save Jews. That “corruption” was praiseworthy. However, when the word corruption is used with respect to moral character, it is necessarily pejorative.

Anyway, we may think of a bucket of words that clearly have disapproval built-in, and a bucket of words that do not necessarily have disapproval built-in. But some words are not so clear. Consider the next list. Some of the words shown below float between those two buckets. When you use any of the words on the following list, is disapproval by you necessarily built-in? Is the word, in your active vocabulary, necessarily pejorative?

atavism

bias

corruption

cult

demagogue

discrimination

dogma

dogmatist

faction

fanaticism

groupthink

ideologue

ideology

interest group

lobbying, lobbyist

prejudice

propaganda

religion

rent-seeking

scofflaw

selfishness

slogan

superstition

When you use a word on that list, is it possible that you would ever use it in a neutral or approving way? These are questions to ask yourself, to discourse responsibly.

My chief goal here is to prompt you to think about your own semantic practice. Does a word, as you use it, have disapproval built into it?

Meanwhile, allow me to tell you a little about my own semantic practice.

Some of my choices

I use the following and with built-in disapproval: atavism, bias, cult, faction, groupthink, ideologue, propaganda, rent-seeking, selfishness, and superstition. Those, for me, are necessarily pejorative—although possibly in a gentle or sympathetic way, as with superstition, sometimes.

The others I either do not use at all or use under a policy of the word not necessarily being pejorative. Some are close calls. The following words are in my active vocabulary and are not necessarily pejorative: discrimination, dogma, ideology, interest group, lobbyist, prejudice, and religion.

Now I offer remarks about foregoing words.

Ideology, ideologue: A lot of people use ideology as necessarily pejorative. For example, R.V. Young defines ideology as “a set of preconceptions about how the world ought to be that displace any genuine perception of the world itself.” But I do not use ideology so narrowly. I use it only in regards to politics, to signify political bent and habits of thought.

One could use “political view” or “political opinion” or “political inclination,” but “ideology” often seems more apt. As for ideologue, I can go along with treating that as necessarily pejorative, to mean someone who twists things to serve his ideology. Those who use ideology as pejorative have a parallel idea in mind: A political bent and habit of thought that is systematically or fundamentally twisted away from the pursuit of wisdom. To signify that, I would say something like “false ideology” or “foolish ideology.”

Dogma and dogmatist are similar. For me, dogmatist is necessarily pejorative, but dogma is not. In Symbolism and Belief (1938), Edwyn Bevan, a buddy of C.S. Lewis, wrote, “A durable religion must involve dogma”, and, “dogma seems to be one of those things which exist in order to be transcended and negated, which yet must be there in order that the act of transcending and negating take place.”

Selfishness is necessarily pejorative for me. It means too focused on one’s own reputation, fame, fortune, and comfort—the “too” implying to a degree that makes action bad for the whole, at least on the margin. Provocative book titles include The Virtue of Selfishness and Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids. Those titles don’t work for me.

Atavism, for me, means not only a throwback, but a throwback not sufficiently subdued, corrected, avoided, or rechanneled—a blameworthy throwback. It is necessarily pejorative, in my usage, as it was in Friedrich Hayek’s.

Faction: Necessarily pejorative for me, and, it seems, for David Hume, who wrote:

As much as legislators and founders of states ought to be honoured and respected among men, as much ought the founders of sects and factions to be detested and hated; because the influence of faction is directly contrary to that of laws. Factions subvert government, render laws impotent, and beget the fiercest animosities among men of the same nation, who ought to give mutual assistance and protection to each other. And what should render the founders of parties more odious is, the difficulty of extirpating these weeds, when once they have taken root in any state. (Hume, “Of Parties in General”)

And for James Madison, too, faction was necessarily pejorative:

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. (Madison, Federalist 10)

Groupthink is necessarily pejorative. In the seminal work Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes (1982), Irving L. Janis begins by examining a number of well-known fiascoes, including the Bay of Pigs and escalation in Vietnam. Janis starts with defectiveness and seeks to explain the absence of correction. He defines groupthink as “members’ strivings for unanimity overriding their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.” He declares the term’s “invidious connotation.”

Rent-seeking I treat like selfishness, groupthink, and faction, as necessarily pejorative. To me, rent-seeking means the seeking of some kind of lucrative privilege, conferred by government, detrimental to the public good.

Propaganda is a close call, but I go with necessarily pejorative. Demagogue too is a close call, but I lean toward not necessarily pejorative.

Again, my goal here is merely to frame the question and prompt you to think about your own semantic practice. You are trying to persuade your reader to disapprove as you do. By thinking about the matter, you may clarify the disapproval that you are communicating. For example, when you call some group a faction, are you expressing disapproval? If so, the reader may expect you to justify the disapproval.

Take responsibility for the tongue you shall use. Part of that is picking your pejoratives.

Karl Krauss said: “My language is the common street prostitute that I turn into a virgin.”

And Michael Polanyi said: “The words I have spoken and am yet to speak mean nothing: it is only I who mean something by them.”

We might ask: Does someone or something mean something by the words generated by ChatGPT? If so, who, or what?

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.