After Brownstone Institute republished my last article on New York City emergency department data, friends made me aware of some pushback from a hospitalist on Twitter. Addressing criticism on every platform is not a wise use of time, but enough of my fellow “Team Reality” colleagues engaged the thread to motivate me to respond.

Critique 1: My analysis relied on medical billing codes.

All covid-19 data — indeed, much medical and death data — relies on codes. Codes represent definitions and guidelines. The key in analysis is understanding what the codes do and don’t represent, and being clear about limitations of those codes as applied to the dataset of interest.

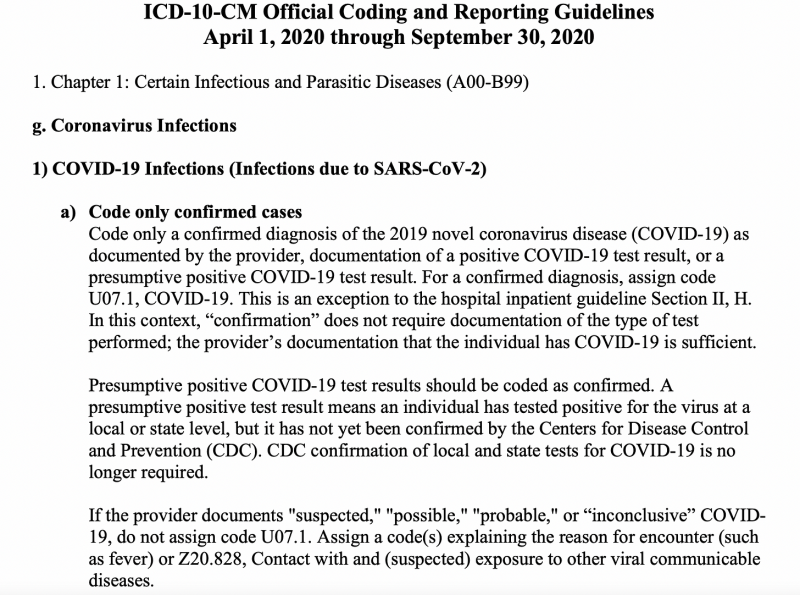

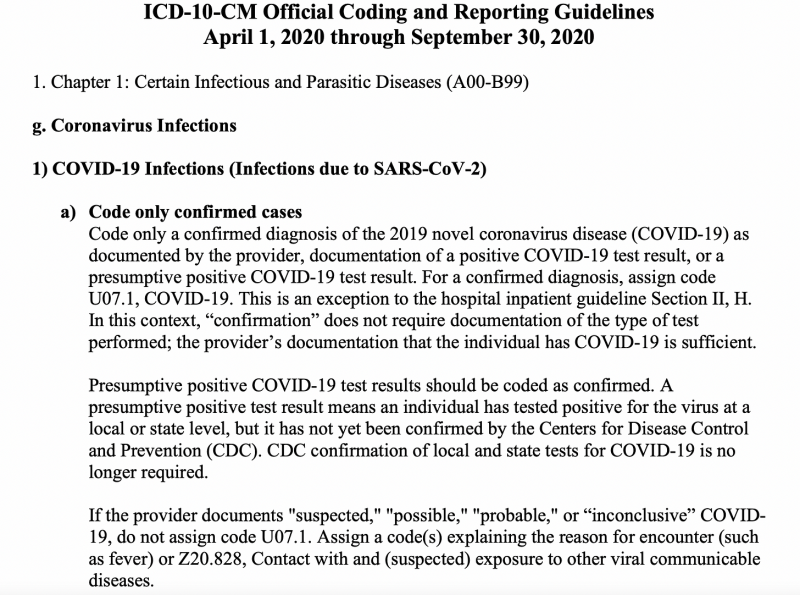

On February 20, 2020, the CDC issued initial guidance for coding encounters related to covid-19.1 The agency updated the guidelines the following month, effective April 1 (screenshot below).

A confirmed case diagnosis did not/does not require a positive covid-19 test result, and a positive test result in the absence of symptoms receives a U07.1 code. I pointed this out in footnote 1 of my November 3rd post.

I could go on and on about the problems our covid case definition hath wrought. (For an excellent primer, see Brock Burt’s thread.) Unfortunately, there is little incentive for officials to be honest about or change it, because doing so would further expose the true toll of vain human efforts to slow/stop an airborne, aerosolized, seasonal respiratory virus that had already been circulating for months, with no real impact on excess death.

One benefit of looking at a range of datasets that rely on the same (bad) case definition, alongside other data that don’t, is that it brings us closer to indicting bad and misleading codes.

Critique 2: Clinically-diagnosed ED visit data “misses” a lot of people who came to the ED with covid.

Whether more people who came to NYC EDs in spring 2020 with covid than were officially diagnosed (at the time or later) is irrelevant to whether city EDs experienced high patient volumes.

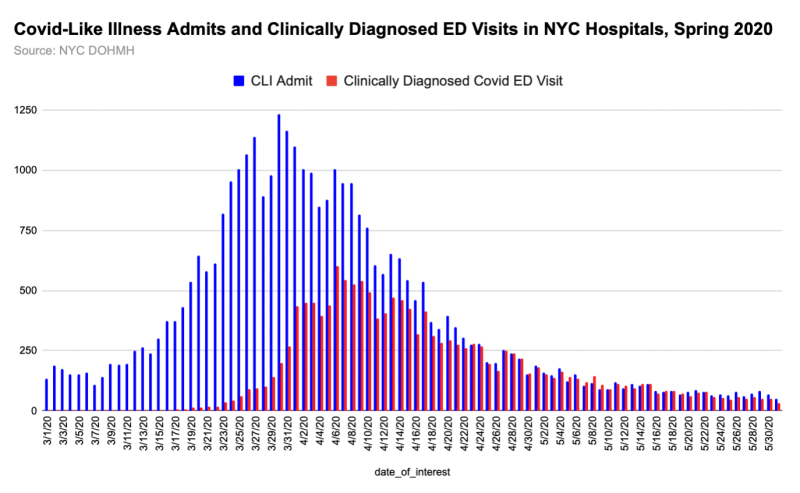

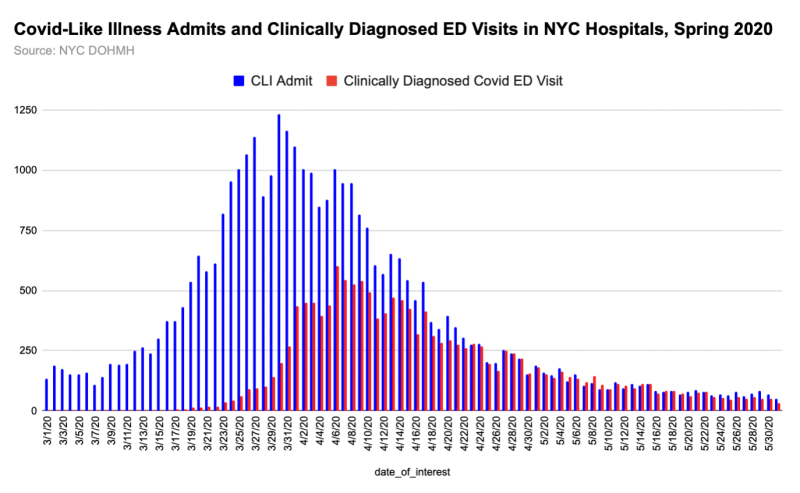

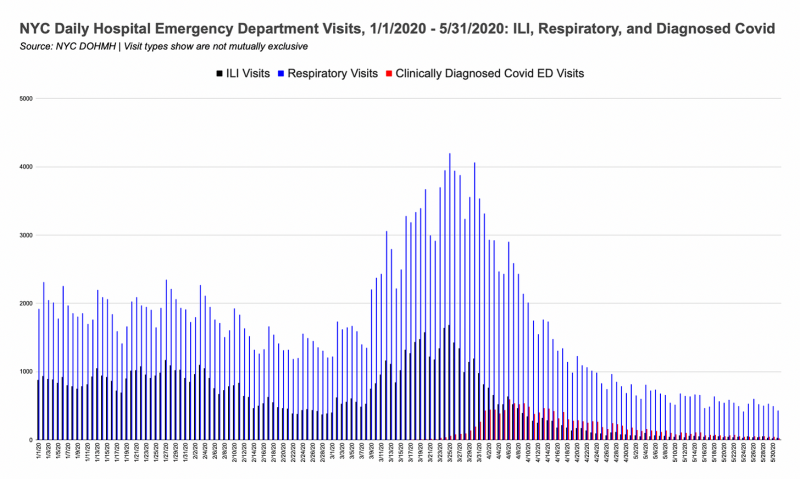

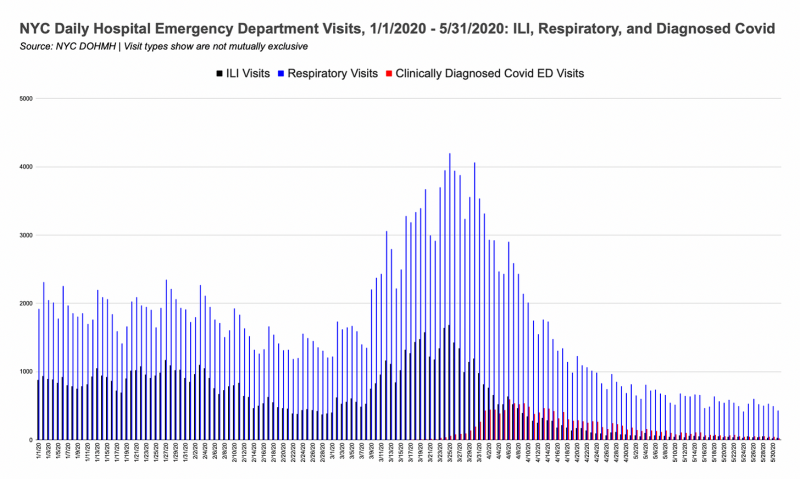

If we want to estimate how many visits potentially didn’t get diagnosed with covid that should have, we can look at 1) the daily number of respiratory visits and influenza-like illness (ILI), and 2) the daily number of admissions for covid-like illness (CLI)2.

Since the CLI definition is very broad — and inclusive of symptoms most closely associated with covid-19 — the difference between CLI admissions and clinically-diagnosed covid visits could represent some portion of any undiagnosed covid among people who came to the ED with symptoms.

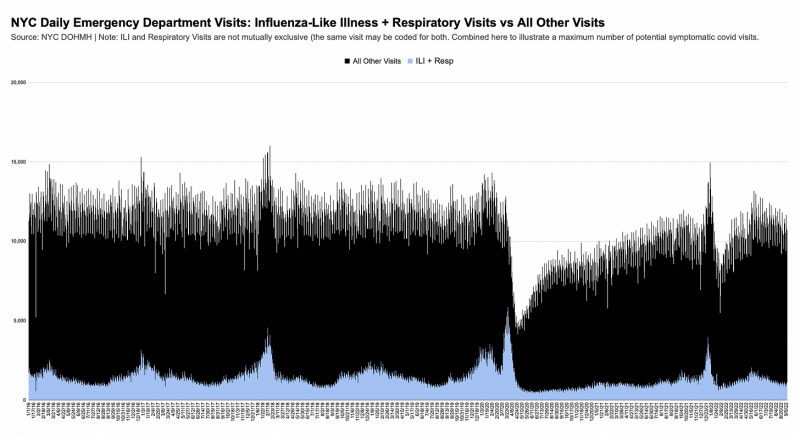

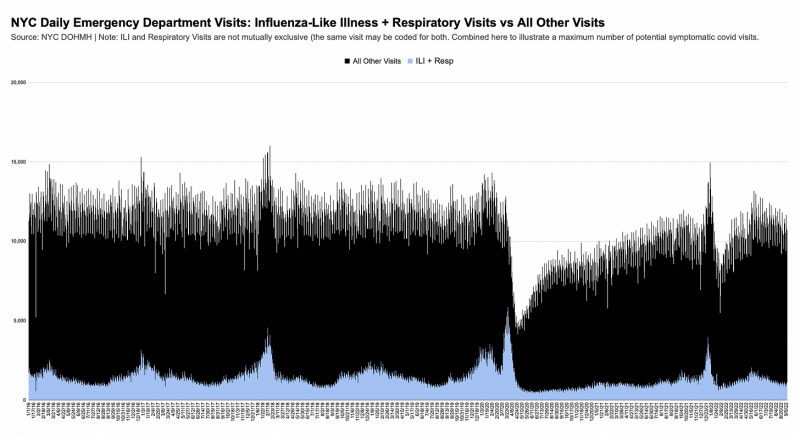

If we want to be even more generous, we could use ILI and respiratory visits combined. The classifications aren’t mutually exclusive, but I’ve added them together in the graph below to show a “maximum” number of people showing up to the ED with any covid-associated symptoms.3

Note that even during the respiratory + ILI spike, ED visit volumes remained normal. It would be extremely bold to assert that 50-75% of people who came to the ED with respiratory symptoms and/or ILI had covid but weren’t diagnosed.

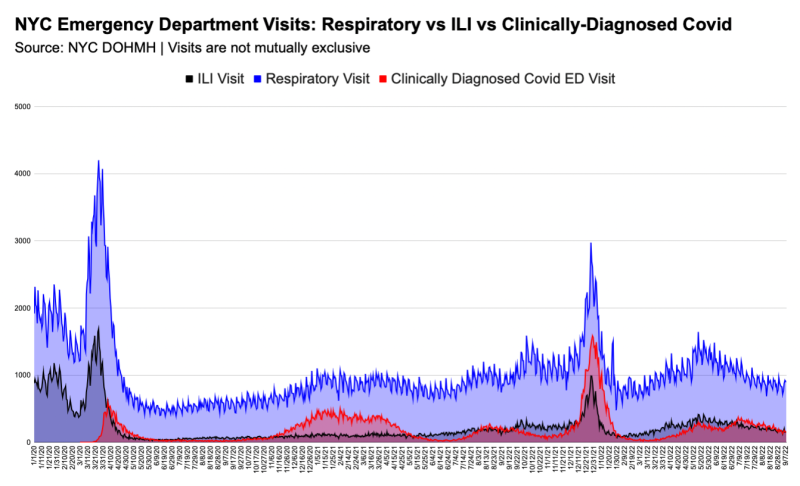

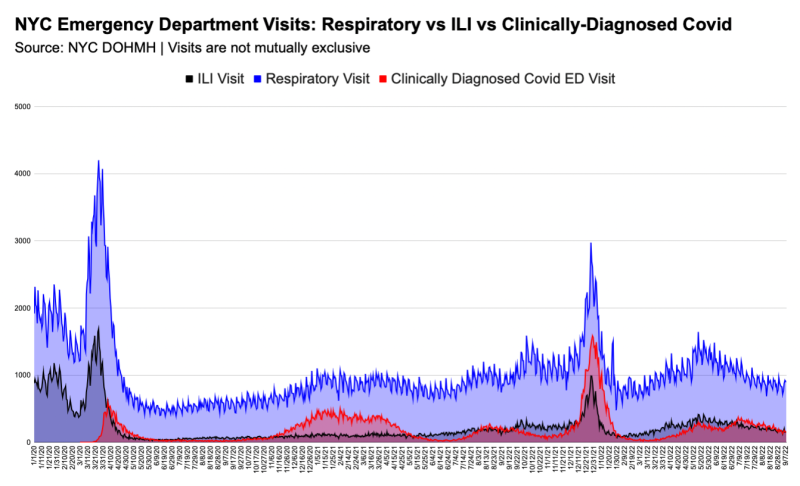

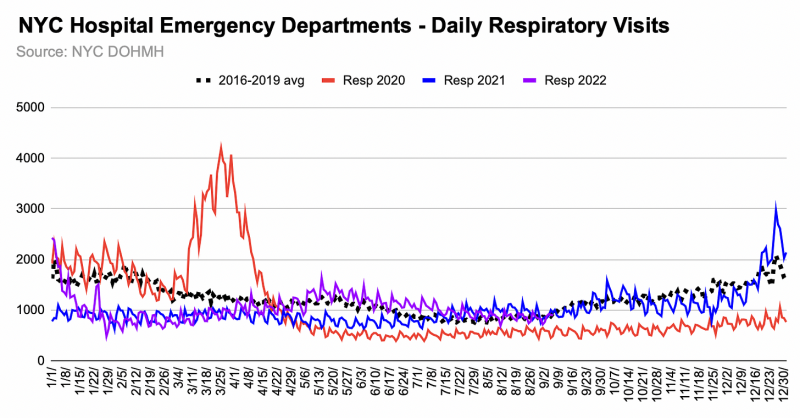

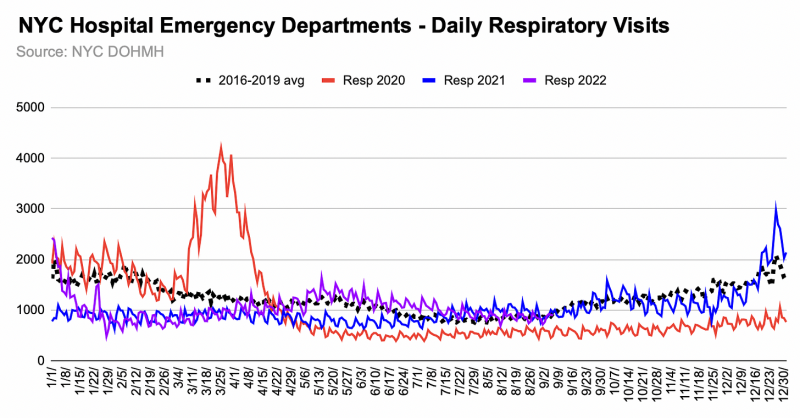

Notably, even though respiratory visits didn’t return to baseline levels until winter 2022, clinically-diagnosed covid visits rose to ~half of respiratory visits in December 2021, and 75% in January 2022. Very strange, indeed, that respiratory visits stayed so low for so long with SARS-CoV-2 circulating everywhere.

We see ILI and respiratory visits spike suddenly as Governor Cuomo issues various orders, but the increase doesn’t last long. I maintain that the timing and magnitude of the rise strongly suggests it was largely panic-induced (as was the spike in EMS calls), rather than attributable to wildfire-esque spread of a virus-deadlier-than-flu that went undetected ‘til lockdowns.4

Critique 3: NYC EDs were overrun by people with covid-19, over capacity for weeks during the initial surge, and had to accommodate critically ill, intubated/vented patients.

The emergency department data I used is citywide and shows visits. To my knowledge, there is no source for how many people are “in” the ED on a given day or time of day. ED “capacity” – if that’s the correct term – can only by inferred from the number and nature of visits.

The hospitalist asserts that I claimed EDs weren’t overrun because there wasn’t a lot of lab-confirmed covid-19 in the ED. This is a misrepresentation of my analysis and the data I showed.

NYC EDs were not overrun, so they certainly couldn’t be overrun by people with covid (undiagnosed or otherwise). And, as I already explained, a clinically-diagnosed covid ED visit did not require a lab-confirmed test.

Data on the daily number of patients intubated citywide and in facility ICUs is available and will be a part of my NYC Inquiry. There is no data source for corroborating claims about ICU-level patients being intubated and vented in EDs. How staff felt in NYC EDs, and why, was not the subject of my November 3rd post.

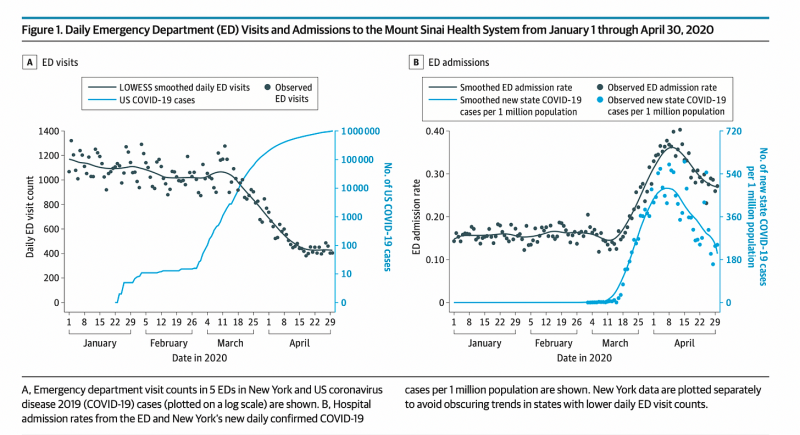

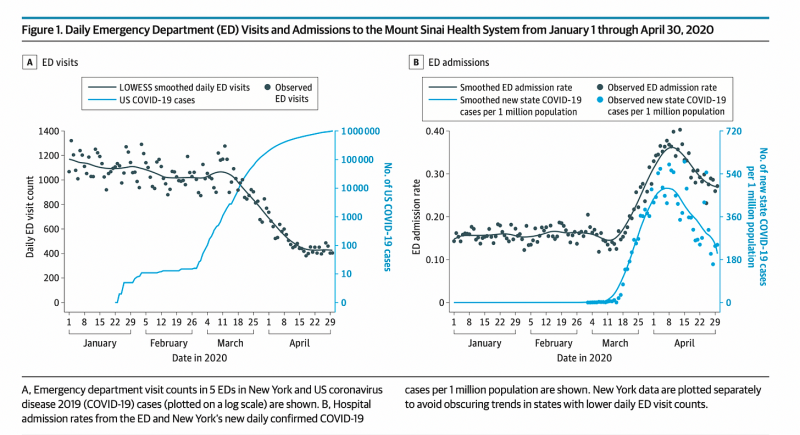

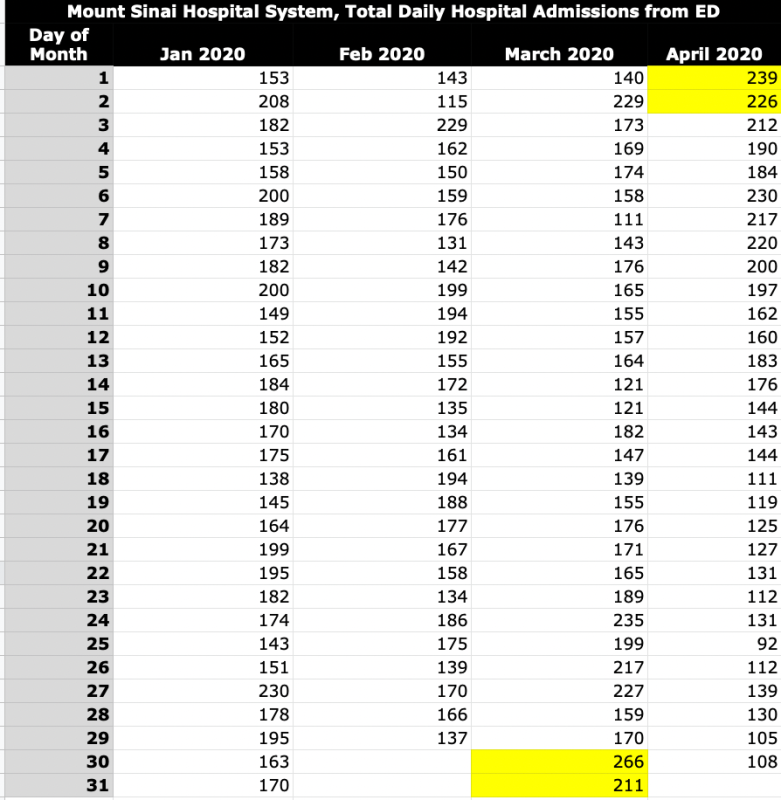

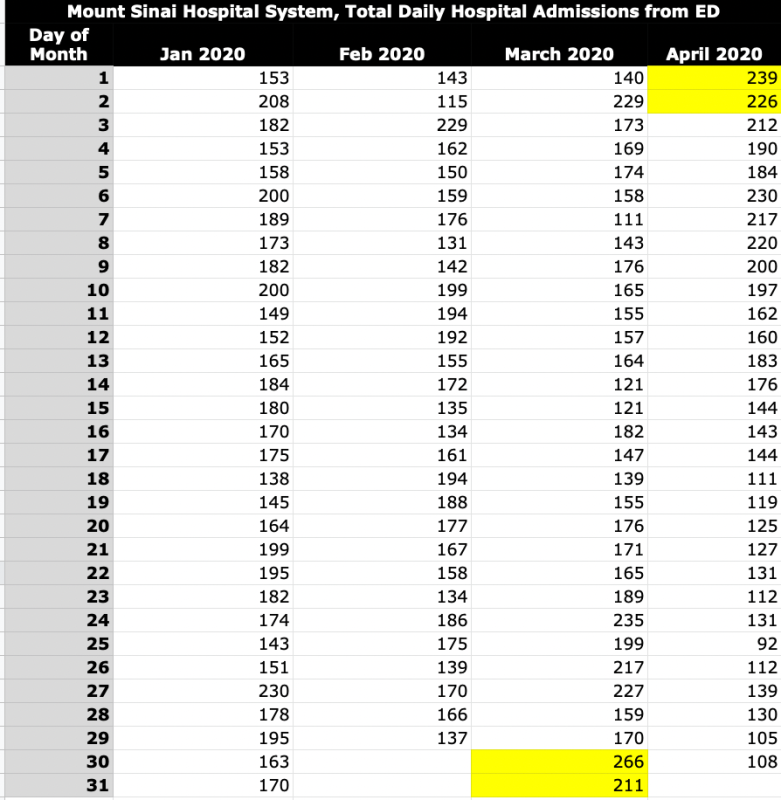

In support of the claim that NYC emergency departments were super-busy, another doctor on Twitter posted a JAMA study, saying it showed a 149% increase in ED admissions in the Mount Sinai Health System in April 2020, alongside a steep decrease in ED visits.

However, graph B in Figure 1 from this study (above) shows admission rates, which were affected by the drop in total visits, and (likely) by the high number of nursing home residents being sent to hospitals (i.e., the quality of patient health).

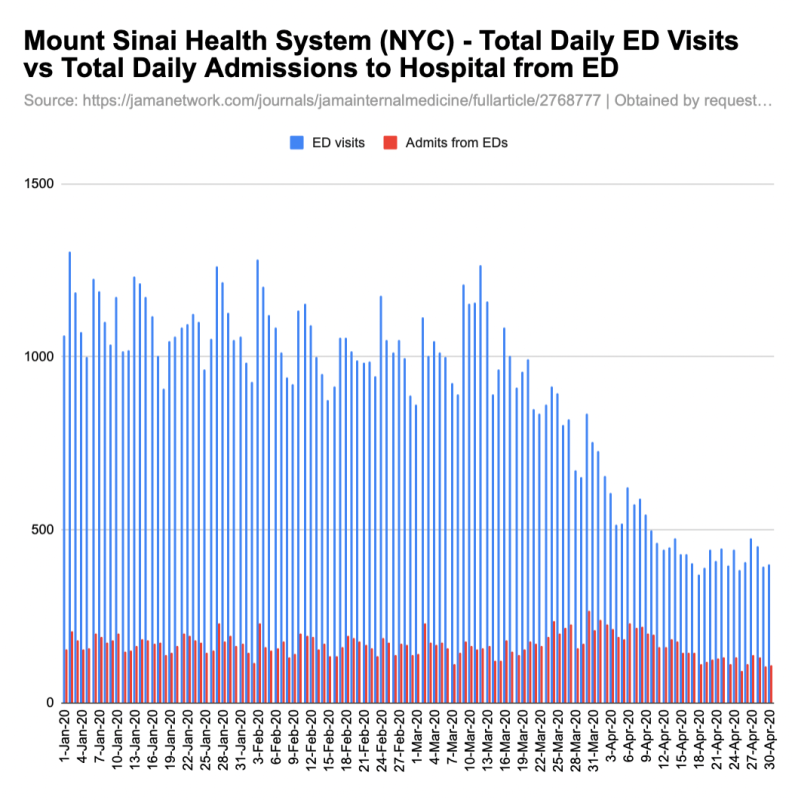

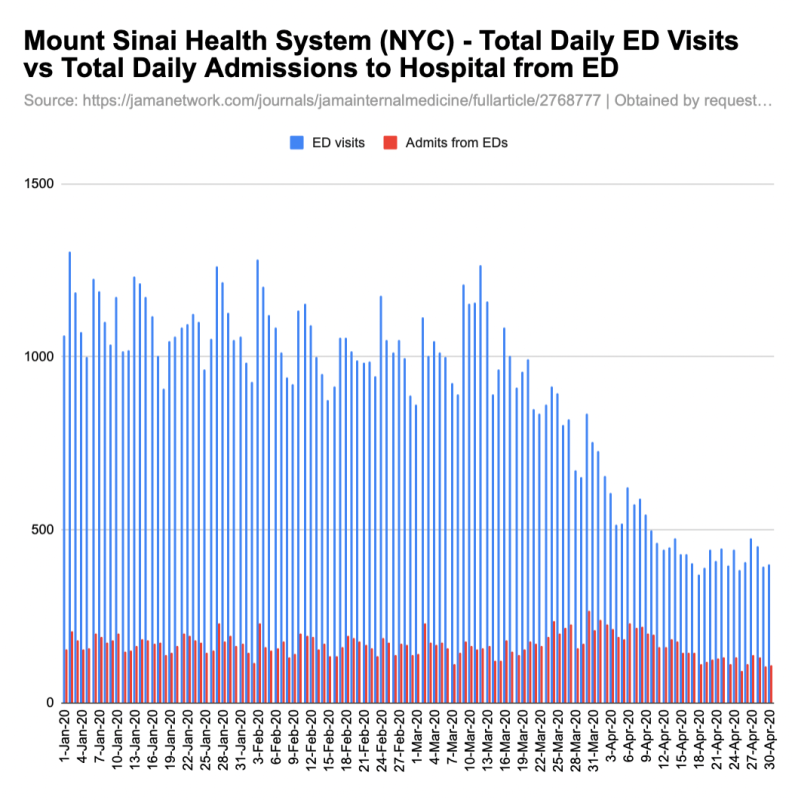

I obtained the underlying raw data for graph B from the study authors. See below for my graph and table.

Mount Sinai’s rise in admissions from the ED was short-lived. The rate increase is more dramatic than the raw-number increase due to the ED visit drop. Without historical data, I can’t say whether the 266 admits from the ED on March 30 was unprecedented, or what admission criteria/protocols were being followed. I don’t have any other information right now about why those patients in the Mount Sinai system were admitted, or whether they were diagnosed with or suspected of having covid-19.

Claim 4: NYC hospitals “had little to no testing in March 2020”. (Implication: If we had more tests, more people coming to the ED would’ve been diagnosed with covid-19.)

Very early on, testing was limited and reserved for those who had traveled to mainland China, had a known exposure to a confirmed covid case, had actual symptoms, etc.

But NYC hospitals had tests in March5. For example, week after obstetricians at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center reported a covid case in an obstetrical patient on March 13, 2020, all women admitted to the labor and delivery unit were being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection.6

While this doesn’t mean every visitor to the emergency room was also being tested, I would expect those most in need of treatment (i.e., with severe symptoms, in high-risk groups) were given a test in the ED or after admission, and were admitted not simply because they tested positive, but because their condition necessitated medical treatment/intervention.

March 13th was also the day New York’s request to approve any lab in the state to do covid testing was granted. In his book, American Crisis: Leadership Lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic, Andrew Cuomo called the approval “a real breakthrough that practically took the FDA out of the lab-approved equation for New York.” Roche’s fully-automated test was also given the green light that day, and the federal government declared covid a national emergency.

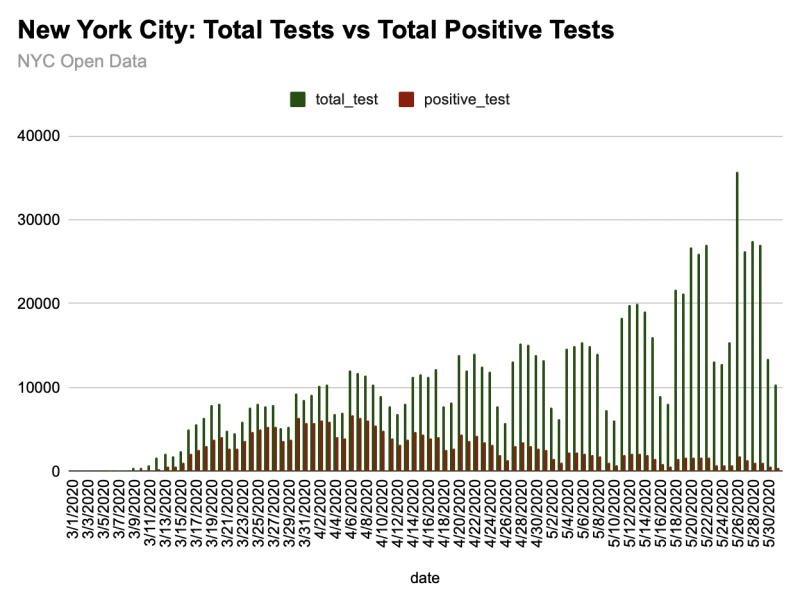

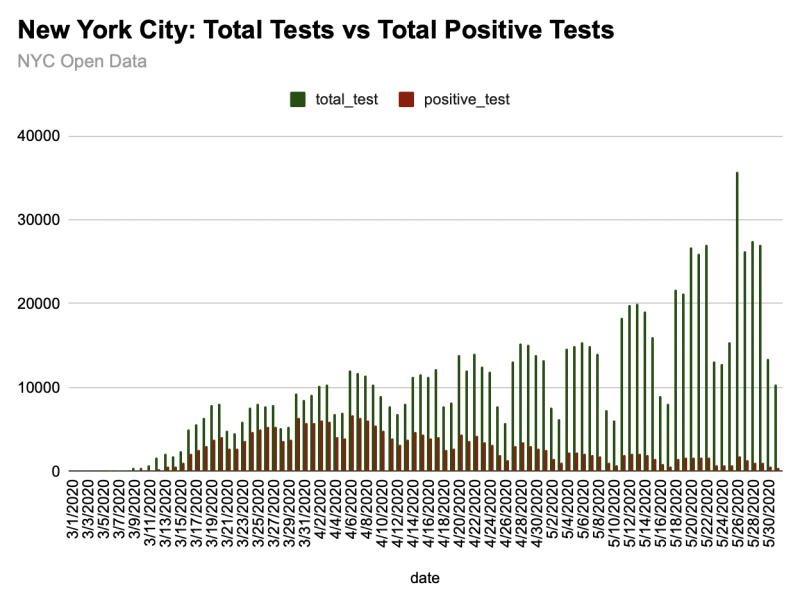

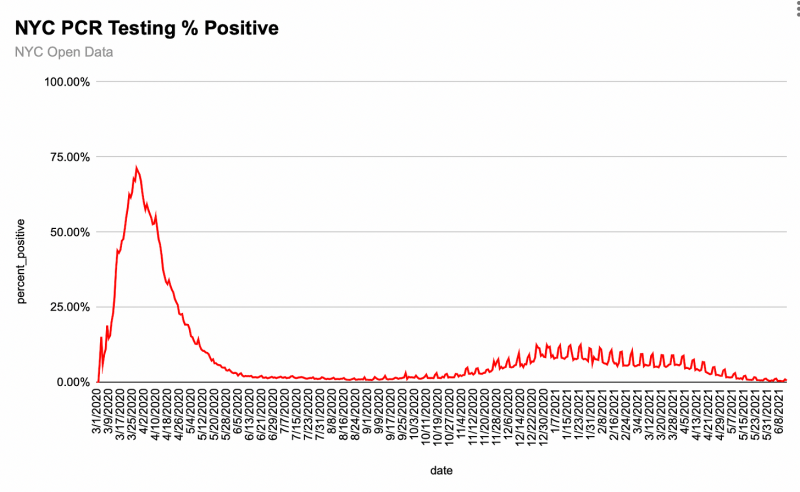

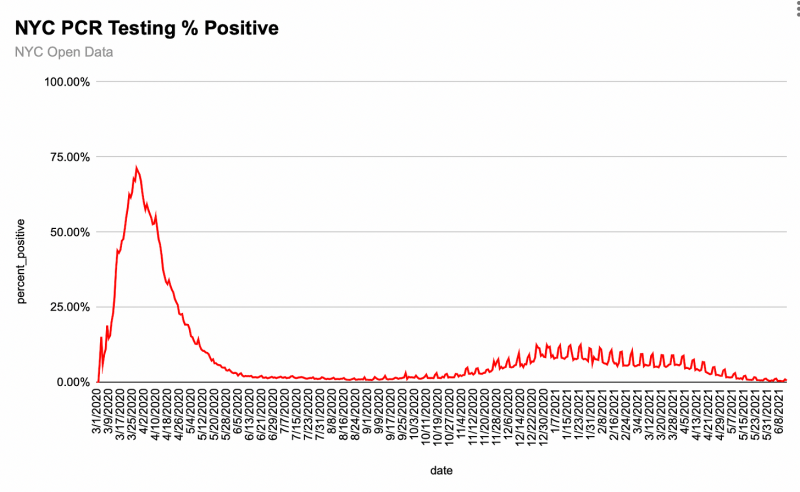

I don’t yet have testing data disaggregated by place, but by early April, the city was giving 10K+ tests a day — mostly in hospitals and nursing homes, if I had to guess.

The positivity rate of 50%-75% apparently didn’t raise questions about whether SARS-CoV-2 had been circulating among millions of people for many months. Instead, it led public health and elected officials to see “spread” and call for more testing.7

Critique 5: Hospitals expanded capacity, non-clinical and non-hospital spaces were used to manage admissions, and census was very high.

This is another criticism that is irrelevant to the analysis I posted. I did not address or show data related to all hospital admissions, nor did I show data on hospital census. I’ll address data on NYC hospital census and capacity in a future article.

Final Thought

I understand that New York City doctors and nurses may find these data challenging to integrate with their “lived experiences” in spring 2020, or may believe that only people who were working in the city’s hospitals at the time – or medical doctors/researchers – should be able to speak to these data.

At this point, I’m not refuting or affirming any person’s or group’s story about those weeks. I’m continuing to examine the numbers, bit by bit, toward developing and strengthening reasonable hypotheses about why NYC is such a “covid outlier” — and whether it’s an exception that proves not just one rule, but many.

1 It’s worth noting that interim guidance for healthcare professionals published in January 2020 was symptom-based, not test-dependent.

2 Covid-Like Illness Admissions: “The number of hospital admissions for influenza-like illness, pneumonia, or include ICD-10-CM code (U07.1) for 2019 novel coronavirus. Influenza-like illness is defined as a mention of either: fever and cough, fever and sore throat, fever and shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, or influenza. Patients whose ICD-10-CM code was subsequently assigned with only an ICD-10-CM code for influenza are excluded. Pneumonia is defined as mention or diagnosis of pneumonia.”

3 Chicago publishes CLI visits to the ED data through 6/2021, but NYC does not. If any reader finds NYC hospital CLI ED visit data, please provide the link in the comments.

4 This week, I received Chicago’s EMS call data for the same time period. I will be posting that in the coming weeks, with a comparison to NYC’s numbers, to further support my *panic* theory.

5 I’m awaiting a response to a records request for daily number of tests administered in NYC hospitals.

6 This wasn’t the only NYC hospital that was universal-screening pregnant women in March 2020. For example: https://search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/en/covidwho-968087 |

7 This dataset’s explainer is interesting: This dataset shows daily citywide counts of persons tested by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT, also known as a molecular test; e.g. a PCR test) for SARS-CoV-2 , counts of persons with positive tests, and the percent positivity. Also included is a calculation of the average percent positivity over a 7-day period. NAAT tests work through direct detection of the virus’s genetic material, and typically involve collecting a nasal swab. These tests are highly accurate and recommended for diagnosing current COVID-19 infection. After specimen collection, molecular tests are processed in a laboratory, and results are electronically reported to the New York State (NYS) Electronic Clinical Laboratory Results System (ECLRS). [emphasis mine]

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.