Many among us weren’t our top notch picture-perfect version of ourselves when society shut down. But we hadn’t quite tipped into the snowball of declining health and well-being.

We came out of the past two years weathered and afflicted by stress and the isolation of living in such divisive times. Many of our troubles are likely still something we can overcome, without permanently impacting our ability to eventually thrive.

Such luxuries of time and eventual progress are denied of the forgotten children we once served with real and meaningful accommodations.

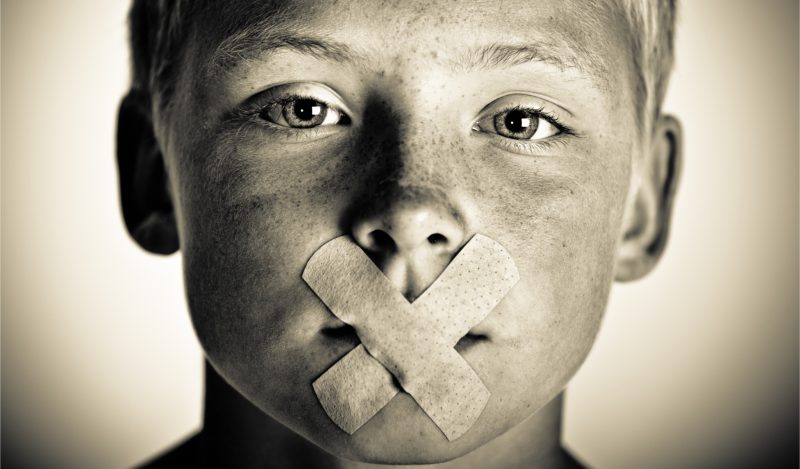

Such grace was denied of Noah, a 4-year old boy from Wisconsin; a playful, social child who is profoundly deaf. When he spent each day of the past year in school with masked, expressionless educators, he received not the just blessing of public accommodation, but a world on mute, cut off from language for the duration of his school day, for during this critical language development stage the lips that he once read as his sole access to understanding his caregivers and peers was denied.

Noah started out with neurotypical language progress, yet suffers from a degenerative form of hearing loss that has only gotten worse as time goes on. Initially, he could only tolerate a hearing aid for about 45 minutes, finding them overstimulating and uncomfortable, but has recently grown accustomed to wearing them for the entirety of his half-day Pre-Kindergarten class.

He knows about a hundred American Sign Language (ASL) hand signs, yet lip reading has been his only access to the teachers who have served him daily, as none of them speak or understand ASL. An interpreter has not been provided until recently, but the district did not have the foresight to hire an employee who elected not to mask, so a foggy window mask on the sole employee responsible for accommodating his needs is yet another obstacle for his family to fight.

Much like the regression of his hearing, his communication as a whole has seen a marked decline. He now avoids eye contact, and it is harder to get him to focus on someone trying to engage with him. He is now nonverbal, but once was capable of saying some words and repeated utterances. Noah plays nicely with neighbor children and does not withdraw during social attempts by peers.

This language decline is not intrinsic. He is trying. The regression that has manifested as a result of this “educational” experience is being done to him. His circumstances are the product of an outright denial of public accommodation for a child with real, immediate needs, by a lazy public school system disregarding the actual harm they are causing.

Noah enjoys tinkering, video games, and has an interest in exploring and dismantling the world around him. Like the volume button of our societal tyranny in recent times, his has been turned all the way down and it has silenced his life, his uncomplaining compliance the price this education system is willing to pay for taking the easy way out.

His sister Sarah, 10, also suffers from significant hearing loss, but already had established friendships before the onset of their shared genetic condition, and is able to tolerate wearing hearing aids for the duration of her school day.

Their condition itself is regressive. Sarah once had the auditory acuity to be able to understand words with her eyes closed, but now cannot decipher what is being said unless able to read lips. She has been asked to try harder to hear her masked, muffled teacher, when asking her instructor to repeat herself, since she relies a great deal on lip reading to supplement her hearing aid.

She is more emotional, and struggles with administrators cutting corners in providing meaningful accommodations, such as failing to provide transcripts of podcasts she’s required to listen to for class. Her hearing is now severely impacted in one ear, with profound hearing loss in the other. She likes talking with friends online and over FaceTime, and enjoys doing her makeup, painting her nails, equestrian riding lessons, swimming, and gymnastics. Sarah has some balance issues, but is still outgoing and enjoys participating in these activities nonetheless.

She is a high-functioning child due to early intervention and meaningful, targeted educational and communication adaptations, which may lead some to perceive her as less impacted by her disability than is her reality.

Thankfully, she has more unmasked peers now that their local mandate was dropped.

Noah has not been as lucky, and there is no guarantee in place by the school system for him to be paired solely with students whose faces he can see. This would require incredibly minimal effort on behalf of his district in the form of a short survey, yet even this small ask remains unaccommodated.

When kids attempt to communicate, but consistently fail to elicit a response from others, they simply stop trying. Irreversible deficits on language and social interaction should be anticipated in such circumstances.

These siblings are the only students with profoundly incapacitating special needs in their school, so it’s not as if school leadership is overwhelmed with needs to accommodate. Both children have the same deaf and hard of hearing teacher for short intervals during the week as their only access to someone who speaks their language.

How Noah is not paired with this educator for the duration of his day is a true misstep and is beyond my comprehension. It is as if they lack the foresight and training in human development to see the outcome of these heinous practices.

When children move to our country from abroad, their parents are accommodated with home language communication and in-school linguistic specialists, helping them cross the bridge from their home language to bilingual territories.

But on a community-wide basis, we have a jaded history of letting our special populations suffer the consequences of poor planning.

Throughout the pandemic, school boards across the country broadcast life-changing information without ASL translators, closed-captioning, or home language translation services, a practice still commonplace after two years. Our myopic understanding of the spectrum of special needs that composes our education populace translates into vast masses of unmet needs.

In the end, all the sacrifices Noah and Sarah have made were for nothing. This school system recently dropped their mask mandate, but still refuses to put Noah with a caregiver whose face they will guarantee he can see, and his current teacher has preferred to wear a mask throughout the pandemic. A cloth mask. Not an N95. Not a PAPR unit. A piece of fabric – unregulated, untested, and expressly non-mitigating for aerosols under every single one of our respiratory protective agencies’ workplace integration standards for airborne viral matter.

Yet instead of surveying their teachers to find a better fit, with someone who doesn’t mind giving a child the slightest bit of dignity (by being more than just a warm body receiving additional funding for his school district for being so inclusive of special populations), his sole ability to communicate remains at the whim of his scared, misinformed teacher.

There are circumstances in which the desires of an employee simply cannot be considered before the real and actual needs of a child. I cannot picture a more restrictive environment for a child with profound hearing loss, while understanding that all students have the right to the least restrictive educational environment under US education law.

Noah and Sarah’s situations warrant an immediate, tailored, extensive, genuinely apologetic response, and immediate language and social intervention strategies to be implemented for this willfully and knowingly isolated little boy.

For the duration of Noah’s educational experience, caregivers have put themselves first, with his needs utterly disregarded, the permanence of their impact on his life and his long-term ability to communicate cruelly displaced by the safety theater imposed by his school system.

We must stop this.

[Names have been changed for privacy of the family, which unfortunately anonymizes the perpetrators of these great offenses.]

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.