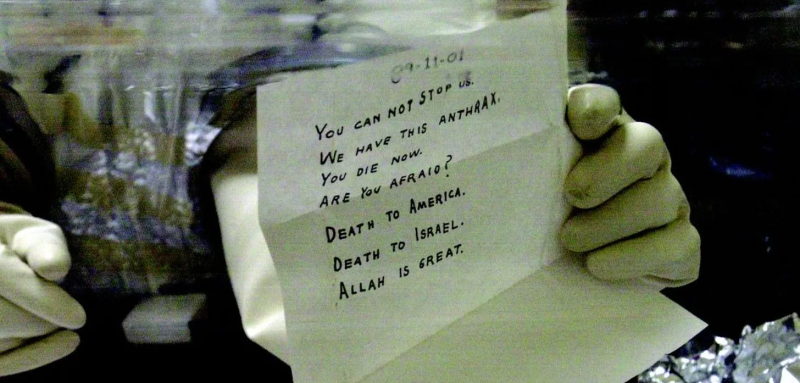

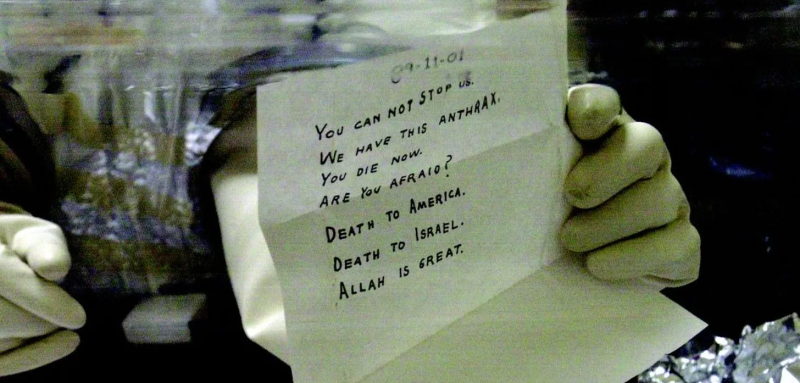

When analysing the 2001 Anthrax attacks in America—a deadly act that unfolded just a week after 9/11, where letters laced with lethal, lab-grade Anthrax spores were sent to prominent media outlets and US Senators, claiming the lives of five people—the official narrative quickly begins to unravel, leaving behind a trail of unsettling questions.

The FBI regarded the Amerithrax investigation as “one of the largest and most complex in the history of law enforcement.”

An FBI science consultant concluded that the powder used in the attack was made with a rare laboratory strain of Anthrax known as Ames, used in research labs worldwide.

In the FBI science briefing’s opening statement of Dr. Vahid Majidi, he stated:

It is the forensic information that determined the source of the 2001 bacillus anthracis mailings to be derived from a unique pool of spore preparations known as RMR-1029 that was maintained at U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, Maryland (USAMRIID).

Notably, the same USAMRIID labs at Fort Detrick were temporarily shut down after failing CDC inspections due to safety concerns in the summer of 2019.

According to the FBI investigation:

In August 2008, Department of Justice and FBI officials announced a breakthrough in the case and released documents and information showing that charges were about to be brought against Dr. Bruce Ivins, who took his own life before those charges could be filed.

For 18 years, Dr. Bruce Ivins had been a senior biodefense researcher at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Fort Detrick, Maryland. Ivins also happened to be co-inventor on two United States patents for anthrax vaccine technology. He died on July 29, 2008, from a paracetamol overdose.

In a ProPublica, PBS Frontline, and McClatchy joint investigation, intriguing details surrounding the case were presented. Notably, long before Ivins became the prime suspect, he had sent his superiors an email offering to help them trace the killer. In his email, Ivins said he had several variants of the Ames strain that could be tested in “ongoing genetic studies” in an attempt to trace the origins of the powder that had killed five. He mentioned several cultures by name, including Ames anthrax that had been grown for him at an Army base in Dugway, Utah.

However, according to prosecutors, this was Ivins’ attempt to hide his guilt by submitting false samples of his Dugway spores in order to mislead the FBI’s investigation. They claimed that “tests on those samples didn’t display the telltale genetic variants later found in the attack powder and in sampling from Ivins’ Dugway flask.”

Yet, records discovered by PBS Frontline, McClatchy, and ProPublica in 2011 revealed publicly for the first time that “Ivins made available at least three other samples that the investigation ultimately found to contain the crucial variants.”

According to ProPublica’s joint investigation:

Paul Kemp, who was Ivins’ lawyer, said the government never told him about two of the samples, a discovery he called “incredible.” The fact that the FBI had multiple samples of Ivins’ spores that genetically matched anthrax in the letters, Kemp said, debunks the charge that the biologist was trying to cover his tracks.

What is even more “incredible” is that the Ames strain database at Iowa State University was destroyed on the orders of the FBI, according to Francis A. Boyle, Professor of International Law, who drafted the Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act of 1989 which passed into law. He stated:

FBI’s decision to order the destruction of the Ames strain database was an obstruction of justice, a federal crime…That collection should have been preserved and protected as evidence. That’s the DNA, the fingerprints right there.

The New York Times reported:

The Iowa State archive was destroyed on Oct. 10 and 11, after relatively brief deliberations with the F.B.I.

The FBI’s glaring omission of crucial evidence concerning Dr. Bruce Ivins’ spore samples and the destruction of the Ames strain database raises urgent questions: why did the Federal Bureau of Investigation appear to be sabotaging its own investigation and in doing so “obstruct justice?”

Could it have been a deliberate effort to shape a narrative more aligned with agenda than truth?

ProPublica’s joint investigation went on to reveal:

To many of Ivins’ former colleagues at the germ research center in Fort Detrick, Md., where they worked, his invitation to test the Dugway material and other spores in his inventory is among numerous indications that the FBI got the wrong man.

What kind of murderer, they wonder, would ask the cops to test his own gun for ballistics?

Furthermore, a 2008 New York Times article reported:

Almost a hundred other people were known to have had access to cultures from the flask [source of anthrax powder], and the scientists say they have no opinion as to whether Dr. Ivins, who committed suicide last month, was the culprit. Some former colleagues and other experts have questioned whether the government was right in suspecting Dr. Ivins, a researcher at the Army Medical Institute of Infectious Diseases in Fort Detrick, Md.

The Hartford Courant reported on further alarming evidence surrounding the story. The following is an extract from the article: “Anthrax Missing From Army Lab.”

Lab specimens of anthrax spores, Ebola virus and other pathogens disappeared from the Army’s biological warfare research facility in the early 1990s, during a turbulent period of labor complaints and recriminations among rival scientists there, documents from an internal Army inquiry show.

The 1992 inquiry also found evidence that someone was secretly entering a lab late at night to conduct unauthorized research, apparently involving anthrax. A numerical counter on a piece of lab equipment had been rolled back to hide work done by the mystery researcher, who left the misspelled label “antrax” in the machine’s electronic memory, according to the documents obtained by The Courant.

In addition, Ivins’ personal emails from 2007, (a year before he died from an overdose) could be viewed as further supporting evidence that the “FBI got the wrong man.”

I’m just so beat. I was at the grand jury for five hours, 3 hours on one day and 2 hours on the next. The questions were so accusatory on so many fronts…I’m not planning on jumping off a bridge or something, so don’t think I’m going suicidal or something. I honestly don’t know what anybody can do…I don’t think there’s much anybody can do. I search emails and documents, trying to find things, trying to help, and look at what it gets me. It makes me wish that I had never gone into biomedical research. (May 24, 2007)

A few months later, the Army microbiologist wrote:

Do you realize that if anybody gets indicted for even the most remote reason with respect to the anthrax letters — something as simple as not locking up spore preps to restrict them from only people in our lab — they face the death penalty? Playing any part, even a minor part such as providing information about how to make spores, or how to make them in broth, how to harvest and purify that could wind up putting one or more hapless persons on death row. Not pleasant to think about. (June 10, 2007)

On August 6, 2008, a federal prosecutor declared that Army researcher Bruce Ivins was the sole person responsible for creating and mailing the Anthrax spores that killed five people in 2001. After a 7-year FBI investigation, the “most complex” case was closed.

Notably, Robert S. Mueller took over as FBI director only a week before 9/11 and the Anthrax-letter attacks that followed. (Mueller would go on to lead a 2-year investigation into President Donald Trump regarding the alleged Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections. In the end, the investigation found no evidence that President Trump or any of his aides coordinated with the Russian government to interfere in the 2016 US election, although it stopped short of exonerating the President.)

A further troubling aspect involved in the Anthrax attacks is that Larry Klayman, chairman of Judicial Watch, noted that administration officials said that some White House staff began taking the antibiotic Cipro on Sept. 11, before the anthrax attacks. Cipro is an antibiotic that can be used to combat Anthrax.

In 2008, the New York Times reported:

“The legal watchdog…was suing the Bush administration for access to documents about last fall’s anthrax attacks, asserting that top officials may have known that the attacks were coming.” Klayman said ”We believe that the White House knew or had reason to know that an anthrax attack was imminent or under way.”

However, a White House spokesman, Gordon Johndroe, denied that assertion.

The only FDA-approved vaccine (first licensed in 1970) to protect against anthrax is BioThrax, first produced by state-owned vaccine lab, Michigan Biologic Products Institute (MBPI), in Lansing, Michigan. The use of BioThrax expanded significantly, when the US military, concerned that Iraq possessed anthrax bioweapons, administered it to 150,000 service members deployed for the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

Disturbingly, according to a Pubmed study: “about 35% [of Gulf War veterans] later developed a multisymptom disease (Gulf War Illness [GWI]), with prominent neurological/cognitive/mood symptoms, among others.”

Authors of another study published in Vaccines wrote: “We report on a highly significant, positive association between anthrax vaccination and occurrence of Gulf War Illness (GWI).”

At a University of Illinois faculty lecture on April 18, 2002, Francis A. Boyle stated:

Bush and Cheney ordered all U.S. armed forces to take experimental medical vaccines for anthrax and botulin. I had no idea why but the reason why was very simple. It came out later. Under Reagan they had shipped these biological agents to Iraq, Iraq had weaponized them, and we knew full well our troops would be vulnerable. So using some of the same technologies, we put these experimental medical vaccines into our own troops, 500,000 of them. Today they suffer from the Gulf War Syndrome. The Pentagon still denies it, but it is a lie.

In 1998, the flailing, state-owned vaccine lab, Michigan Biologic Products Institute (MBPI) was controversially sold well below market value to the for-profit company, BioPort Corp. (later renamed Emergent BioSolutions). At the time, MBPI had already failed several FDA inspections (1993, 1997).

An article in the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH) outlines the acquisition of MPBI by BioPort. Shortly after securing this pivotal purchase, BioPort was showered with a highly lucrative Department of Defense (DOD) contract.

BioPort paid $ 3.28 million in cash for MBPI, financing the rest of the $ 25 million cost with loans from the state of Michigan. Eleven days after the sale was finalized, in September 1998, DOD awarded BioPort a $ 45 million contract to supply anthrax vaccine to the US armed forces. The contract required the government to pay for up to 75% of the cost of the vaccine, even if the vaccine failed to be licensed for use.

It’s baffling how the US government would lock itself into such a predatory contract—committing to pay up to 75% of a staggering $45 million, even if the vaccine never received approval for use. In some way, it acts as a haunting precursor to the infamous Covid-19 vaccine contracts that followed, where profits for vaccine manufacturers were secured regardless of outcomes or harms caused by their products.

Emergent BioSolutions emerged as the sole producer and supplier of BioThrax to the US military, coincidentally just around the time when the mandatory Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program (AVIP) was set up under the Clinton Administration, that same year, in 1998.

The timing of the acquisition, and the swift financial windfall of the DOD contract all converging at a period when Emergent BioSolutions would play a critical role in supplying the military with BioThrax through AVIP—setting the stage for its meteoric rise in the biodefense industry—paints a picture that feels almost as if it had been planned.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.