Thanks to the Twitter Files, we’ve known for a while that the company’s official censorship partnerships extended far beyond the United States. In Australia, for instance, the company had extremely close contact with the Department of Home Affairs (DHA), whose responsibilities include oversight of national security, law enforcement, border control and the country’s lead intelligence agency, the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO).

Just-released Freedom of Information Act documents reveal that Twitter received 4,213 requests from the DHA over a period of years, as reported in The Australian. However, the information gleaned from the request by Senator Alex Antic revealed little regarding the reasoning behind these requests, nor just how close the relationship was.

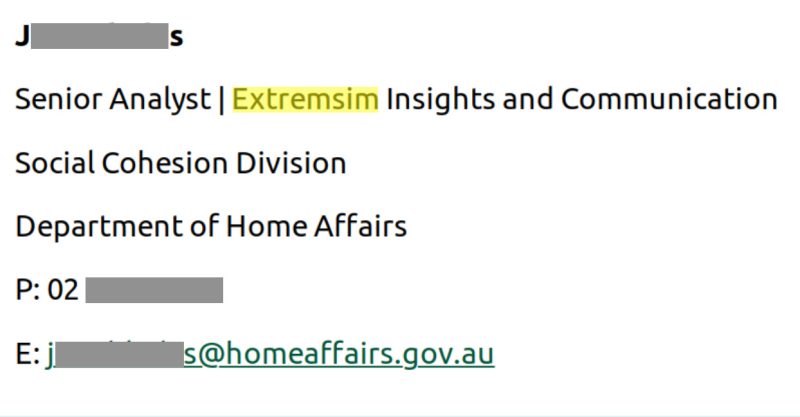

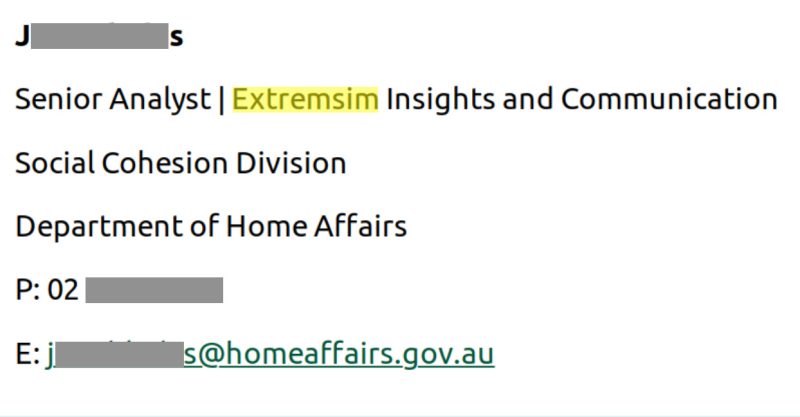

In the #TwitterFiles, Racket found 18 DHA emails, collectively requesting 222 tweets be taken down. Jokes and information that later turned out to be true were frequently included in the censorship requests, which came from something called the “Social Cohesion Division” of the DHA’s “Extremism Insights and Communication” office, not that DHA staffers were entirely sure of their spelling in every case:

This is anti-disinformation 101: a group that can’t spellcheck becoming the “fact-checking” authority for an entire nation, and as we’ll later learn, globally. The same level of care was seemingly paid to requests and the value of free speech more broadly.

Housing Covid-19 censorship management in an intelligence office normally dedicated to monitoring political extremism mirrors the broader global trend highlighted by earlier #TwitterFiles reporting — namely, that with the wind down of the War on Terror, the intelligence community has switched its attention to Countering Violent Extremism. This, in turn, provided broader cover for the censorship of disfavoured internal groups, like for instance vaccination skeptics or even just anti-lockdown activists.

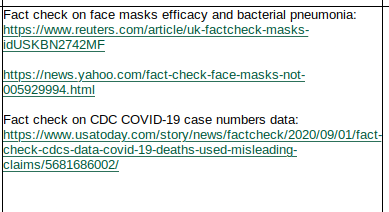

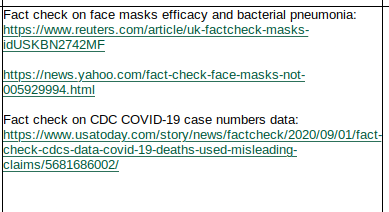

Whether or not any staff had public health expertise remains unknown. The DHA rarely provided evidence for their counterclaims and where they do, they rely on “fact-checking” organizations like Yahoo! and USA Today, rather than on Australia’s own scientists.

It’s not possible to establish what public health competencies existed within a team dedicated to “extremism” and “social cohesion” that appear to have avoided making use of Government scientists.

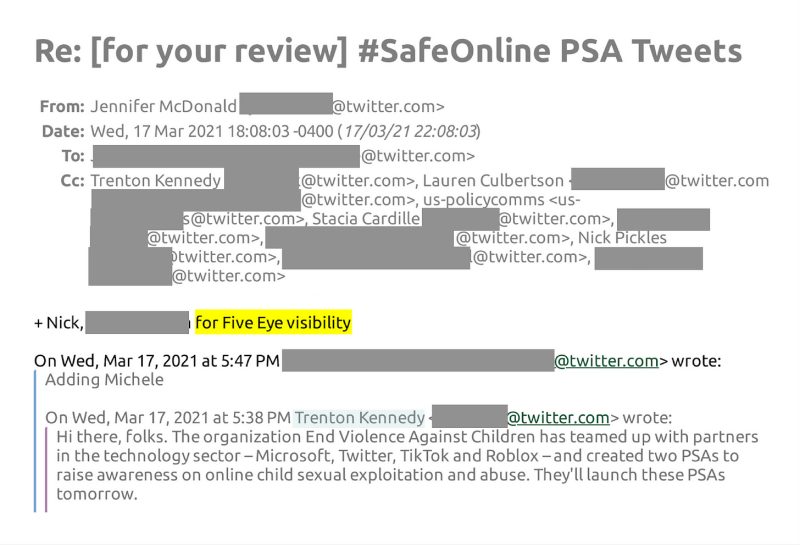

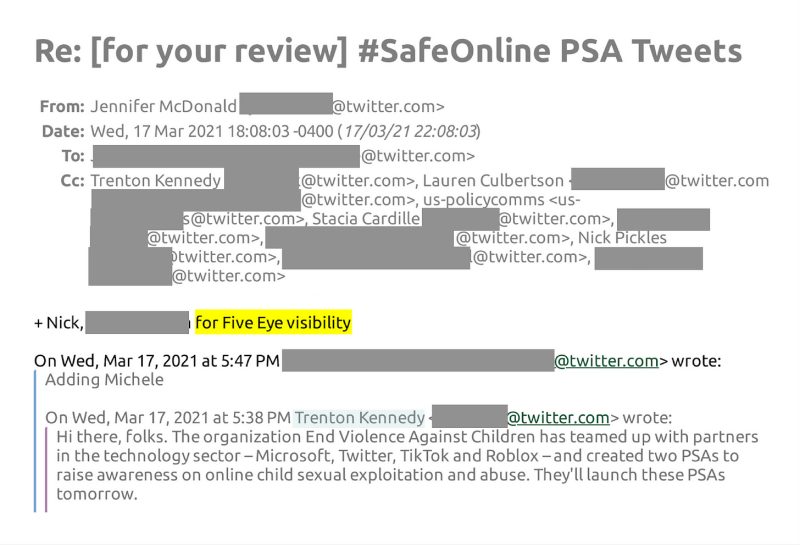

Twitter staffers were under no illusion about who they were working with. On one occasion, a staffer suggested adding senior executives to an email chain for enhanced “Five Eye Visibility” on a series of Public Service Announcements. “Five Eyes” is the term given to the intelligence-sharing group that includes the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

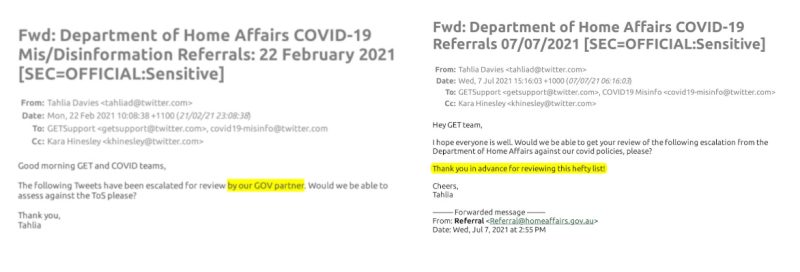

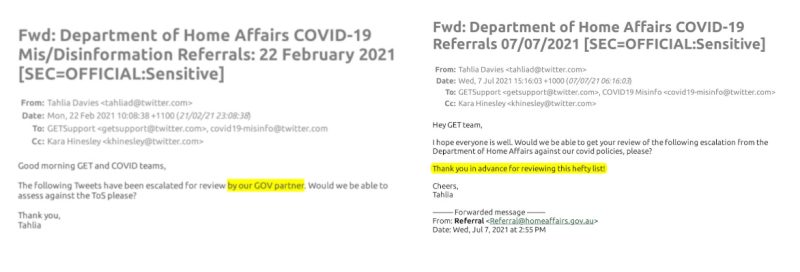

As is the case with American counterparts, Twitter didn’t just seek to comply with government requests, but frequently referred to the DHA as a “partner.” Twitter’s hospitality also left them open to large-scale requests. “Thank you in advance for reviewing this hefty list!” was the response when DHA sent 44 requests on July 7, 2021:

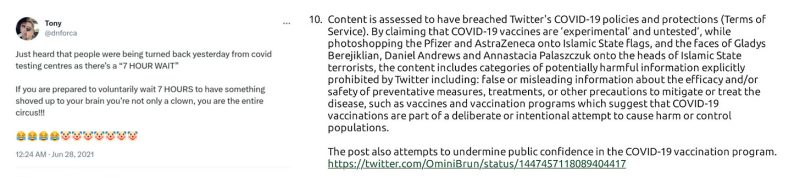

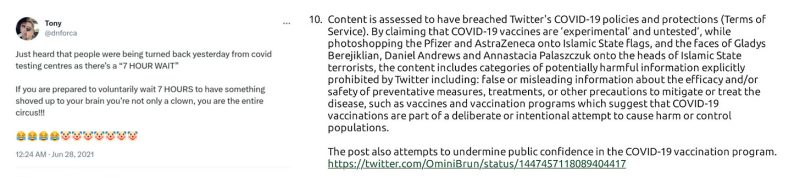

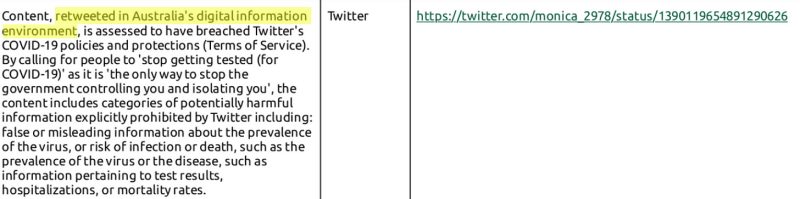

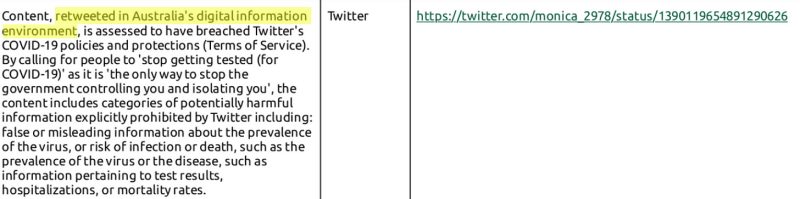

These “hefty lists” included jokes, accounts with as few as 20 followers, claims that turned out to be true, and non-Australians “circulating a claim in Australia’s digital information environment.”

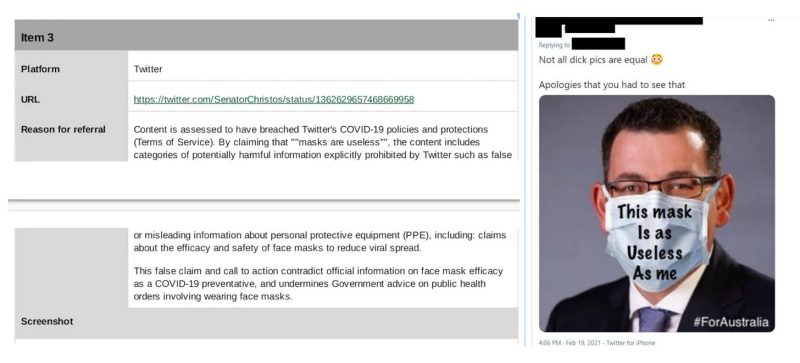

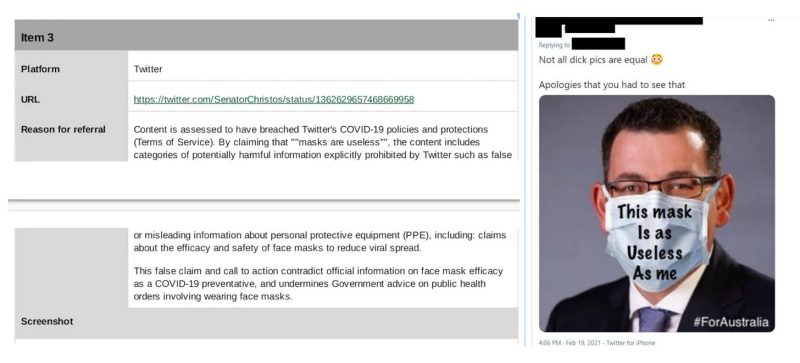

Even a humorous commentary on masks was deemed too much for the fun police. In one case, a mere reply to a tweet claiming “masks are useless” was considered to have contradicted “official information,” making it “potentially harmful”:

DHA called upon Twitter’s own policy that penalized questioning the efficacy of masks. This is ironic, considering a recent Cochrane Review meta-study of masks concluded, “The pooled results of RCTs [randomized control trials] did not show a clear reduction in respiratory viral infection with the use of medical/surgical masks.” Cochrane is considered the gold standard in medical meta-analysis. (The author admits to previously being an enthusiastic mask tragic).

Regardless, the conclusion of DHA and Twitter was that “government officials” should never be challenged, and that discussing contested topics requires banishment to digital Siberia, to say nothing of what used to be a time-honored Australian tradition of poking fun at authority. (The account in question has been suspended).

Similarly, in the “can’t take a joke” category, the DHA apparently believed that a Tweeter thought that the swab used for PCR testing really was “shoved up to your brain.” Or, perhaps they didn’t really believe that, and just wanted the user off the Internet. There’s no way to tell. (The DHA declined a request for comment). At least this request was denied:

In an even greater example of micro-management, the DHA targeted the tiniest of accounts. One doctor caught in the censorship dragnet had just 20 followers. Another Tweet that DHS asked to take down recommended the use of steroids for treating Covid-19, which has since become a common hospital protocol. Despite not garnering a single like and only one retweet, the “Extremsim” team wanted the tweet removed.

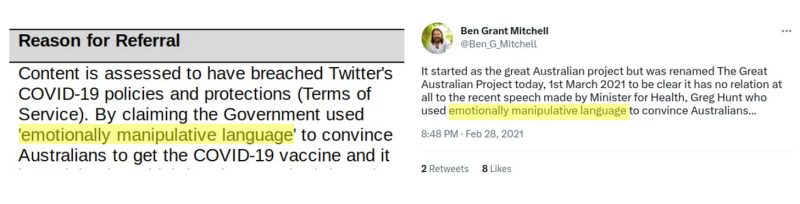

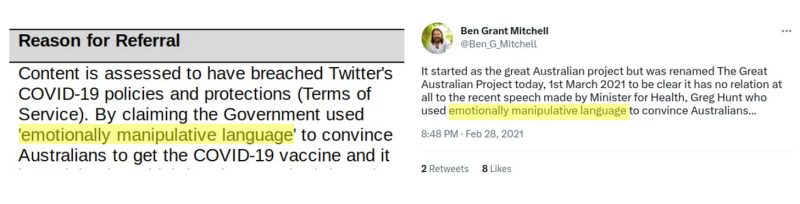

The DHA went well beyond even pretending to police mis- and disinformation. In one case, they argued a post should be removed because a user claimed the government — specifically the Minister for Health — had used “emotionally manipulative language.” The tweet in question (below) garnered just 8 likes and 2 retweets, and again escaped the micro-managers.

In some places the DHA seemed to deem itself sovereign over the entire Internet, targeting non-Australians under the spurious logic that they were “circulating a claim in Australia’s digital information environment.” Essentially, Australians appeared to be asserting jurisdiction even over non-Australian accounts, and in some cases, content that inspired complaints looks to have been pulled entirely from Twitter. What was the legal basis for a foreign government flagging the content from non-citizens for removal?

During the Covid-19 crisis, the Australian government appears to have taken the same approach as its Five Eye cousins, freely mixing concepts of violent extremism and “social cohesion” with legitimate concerns of citizens regarding government panic, lack of expertise, and overreach. From our review, little to none of the content that was flagged came from “extremists.” Rather it was and is from everyday Australians and foreigners who disagreed with government policy. Some of their claims are indeed far-out and/or at least esoteric, but “characters” are part of life, and being unusual doesn’t justify a dragnet approach to censorship.

The Australian stereotype of mocking self-important authorities was tepid at best during the crisis, and what questioning of authority did take place appears to have been quickly memory-holed by the spell-checkers-turned-fact-checkers at the Department of Home Affairs “Extremsim” team. With each passing day, Idiocracy is looking more and more like prophecy.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.