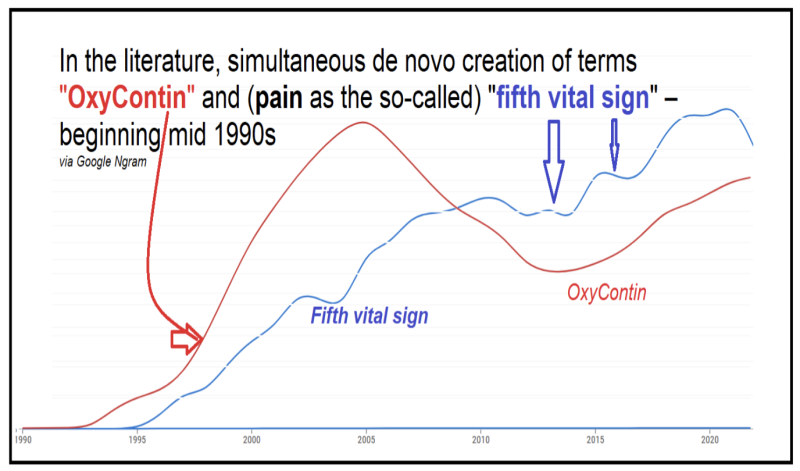

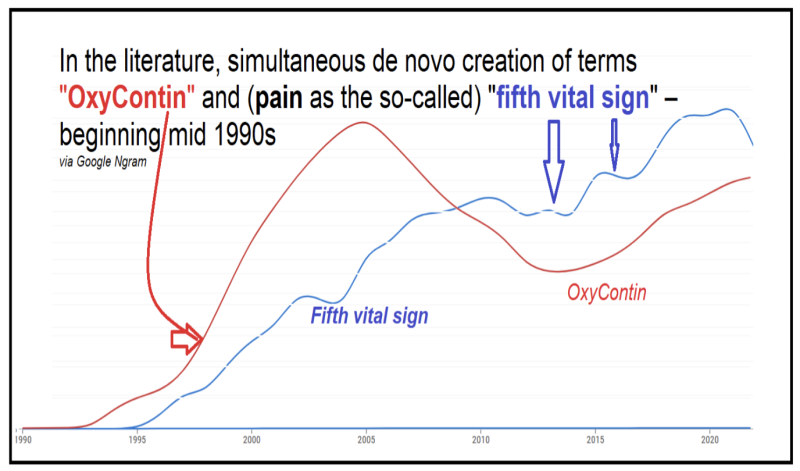

Purdue Pharma’s story unfolds as a Shakespearean tragedy. Like Julius Caesar, whose ascent was made possible by those who later betrayed him, Purdue rose on the government’s push for broader pain management—“pain as the fifth vital sign”—and FDA approvals of its products.

The company addressed a legitimate medical need but became the scapegoat when perceptions (of a long pre-existing) opioid crisis erupted. Stabbed in the back by the very institutions that once supported it, Purdue bore the brunt of public and legal fury (like King Lear’s Cordelia, to add a Shakespearean metaphor), while the systemic issues that enabled the crisis—unchecked prescriptions, pill mills, illicit drug trade (heroin, fentanyl), and government-supported maintenance therapies—remained relatively untouched.

Purdue Pharma: Opioid Crisis Villain, or Easy Target?

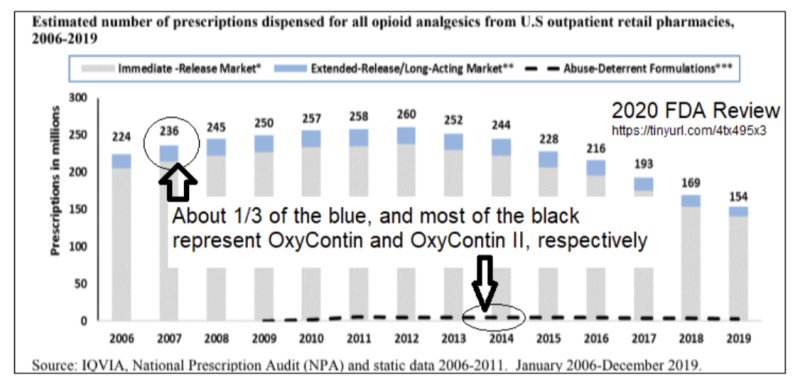

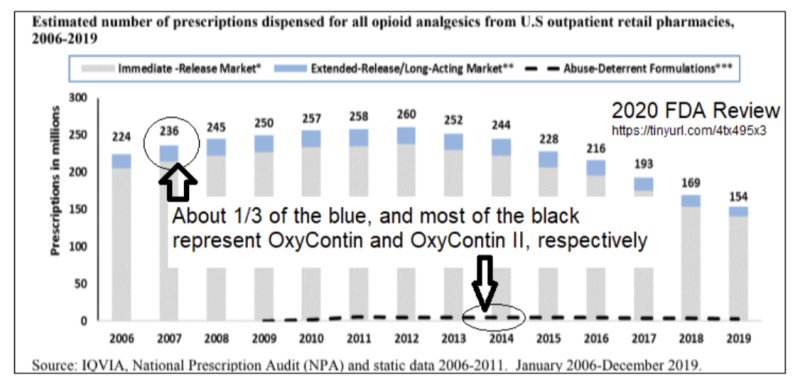

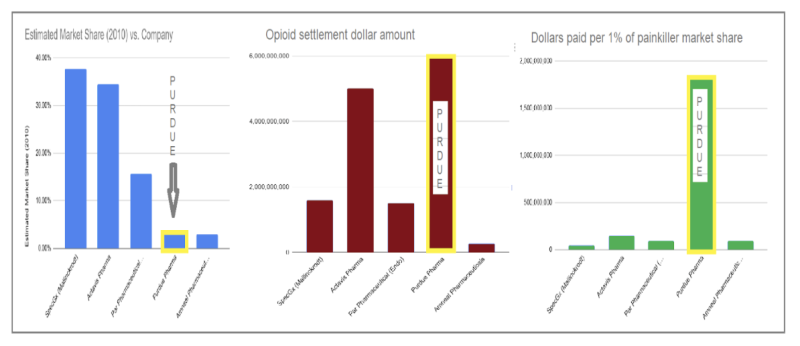

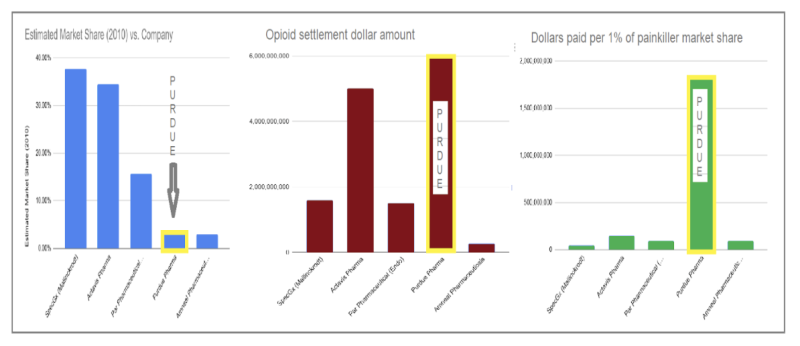

Purdue Pharma became synonymous with the opioid crisis, largely due to high-profile lawsuits and media portrayals in Painkiller and Dopesick. Yet, Purdue’s OxyContin maximally held only 4% of the opioid painkiller market, dwarfed by companies like Mallinckrodt, Actavis, and Endo Pharmaceuticals, which together produced 88% of opioids.

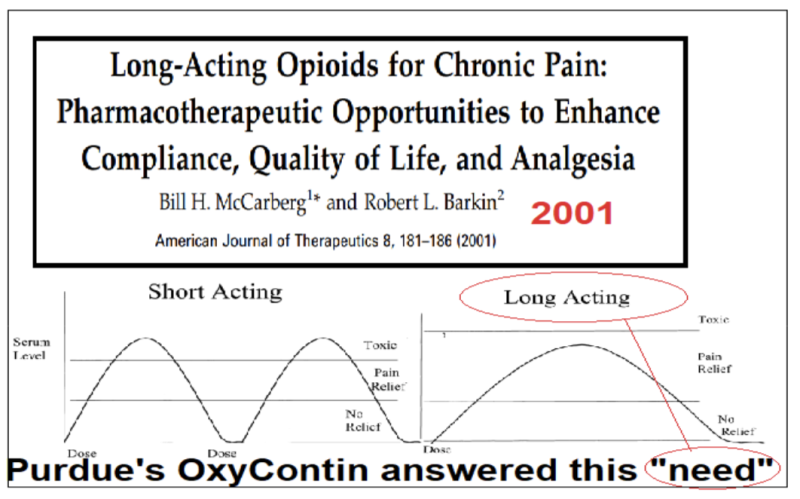

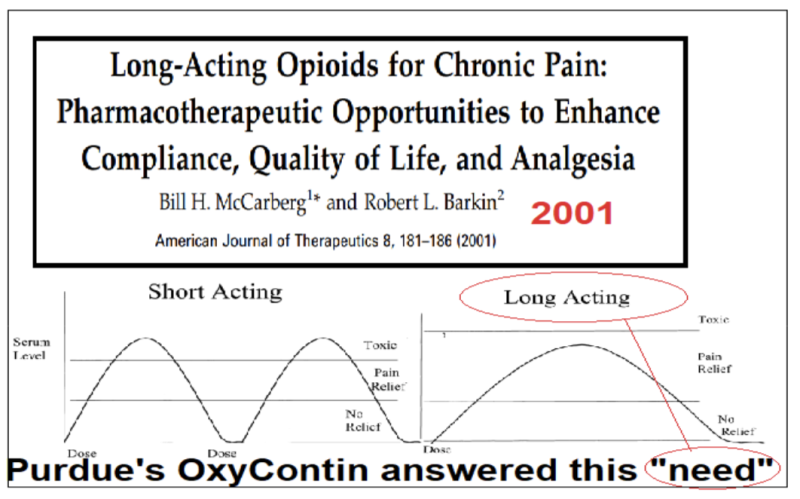

Purdue stood out not because it flooded the market, but because it had developed a “boutique” product (and more importantly in the aftermath, at “boutique” prices)– one crafted in response to the prevailing medical thinking of the time, which emphasized the need for long-acting opioids in managing chronic pain. Studies like 2001’s Long-acting Opioids for Chronic Pain concluded that “long-acting opioids offer distinct advantages over short-acting opioids” by enhancing compliance, quality of life, and stable pain relief.

Purdue’s 1996 OxyContin was precisely aligned with this prevailing medical consensus.

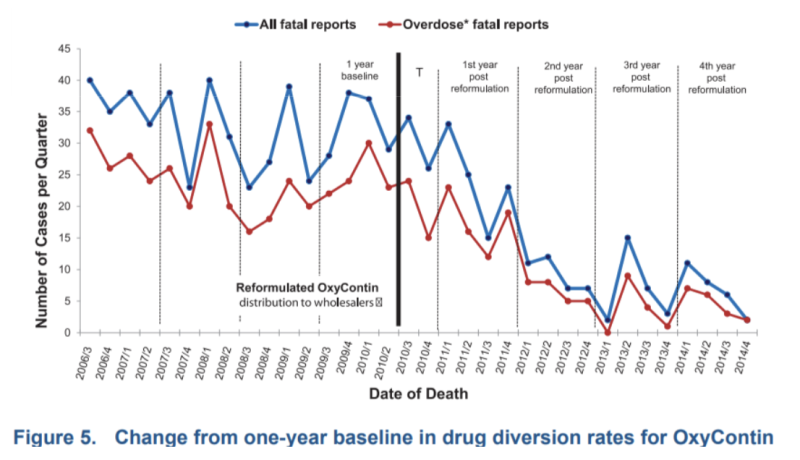

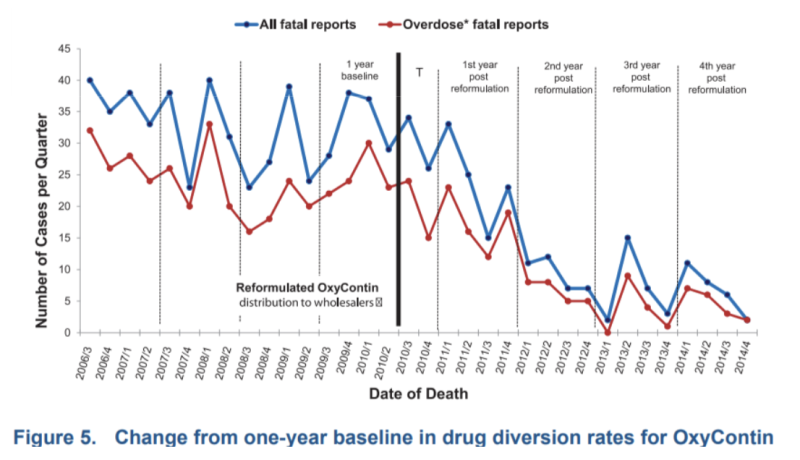

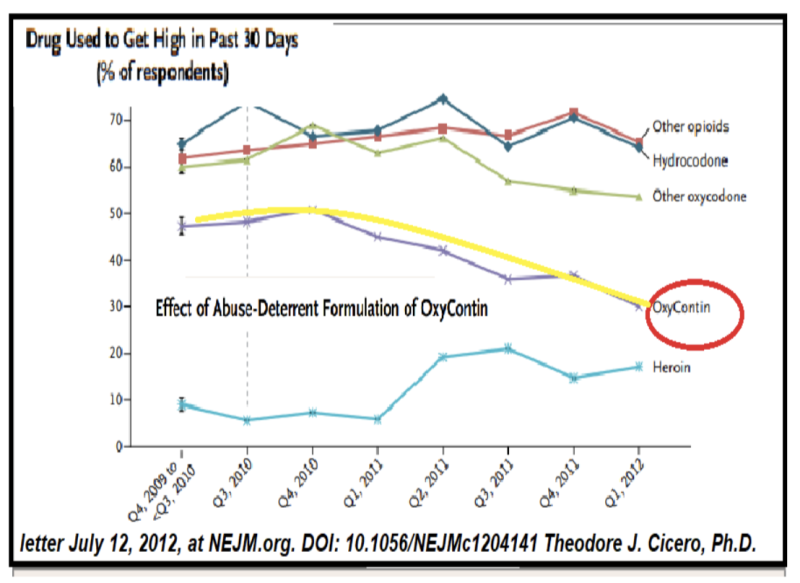

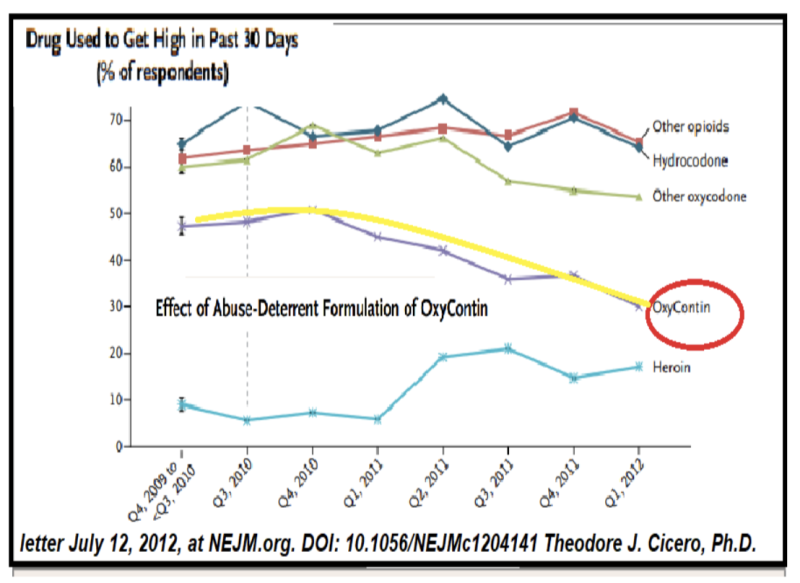

In 2010, Purdue went a step further with the introduction of a groundbreaking “abuse-deterrent formulation” (ADF)—what we might call “OxyContin II”—designed to make tampering difficult and misuse not worth the effort. This reformulation, which had required substantial investment and innovation, was the first of its kind and proved IMMEDIATELY effective in curbing abuse.

In an industry dominated by generic manufacturers producing much simpler morphine analogues, Purdue’s innovation was rare, and the FDA found it so compelling that similar ADF principles were later applied to government-endorsed drugs like Suboxone (to prevent duplication of methadone’s easy diversion).

“(OxyContin II is)…a step in the right direction,” said the FDA’s Bob Rappaport, MD, in 2010.

According to the lawsuit(s), Purdue’s actions “fed the addiction” of a generation, causing widespread harm. Yet this focus on Purdue ignores the broader context, akin to blaming doughnuts for obesity while running a bakery.

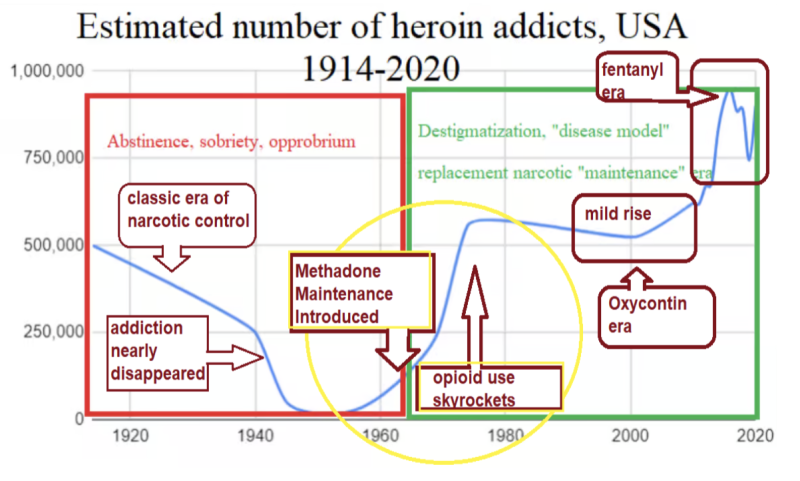

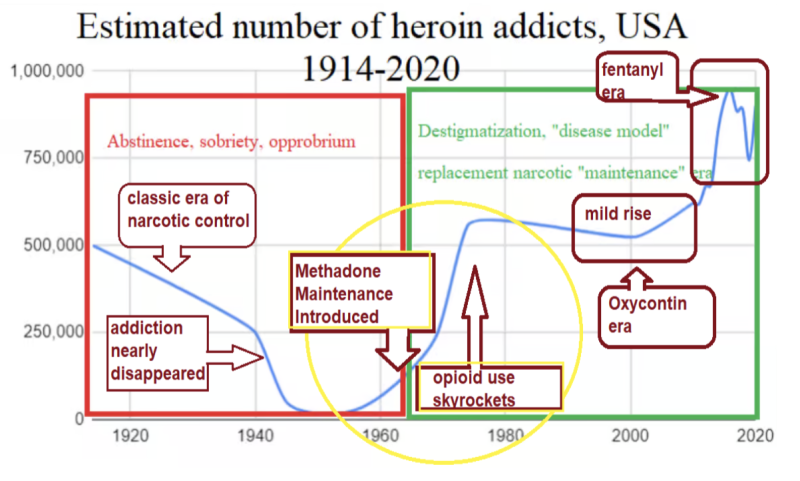

Government-endorsed methadone and Suboxone have long expanded the narcotic user base, priming the opioid crisis. The roots of this epidemic trace back to the 1960s, with the shift toward “medicalizing” addiction through maintenance therapies, which significantly increased baseline narcotic use and dependency. For a detailed historical perspective and market analysis, see my “Methadone Maintenance Ignited America’s Opioid Crisis.”

The irony is stark: despite holding only a 3.3% market share, Purdue paid settlements at a rate 43 times higher than the largest opioid producer. Precisely like a wealthy spouse in a bitter divorce, Purdue bore the brunt of public and legal outrage, while poorer industry players without abuse-deterrent strategies escaped scrutiny. The government killed Purdue, yet (as with post-settlement tobacco) opioids remain with the challenge (e. g. fentanyl) greater than ever.

Purdue’s Original Intent

Purdue Pharma’s intent in marketing OxyContin was not to create (or expand) an opioid epidemic. Opioids have always been uniquely reliable—performing exactly as intended, consistently relieving pain — and inducing a sense of pleasure, whether from physical or psychological relief, so intense it may have recipients “coming back for more;” often to the point of addiction. Unlike any other drug, opioids deliver this effect universally, across individuals and even across species, making them both powerful and perilous. This precise, consistent effect creates a complex marketplace with three types of users:

- those with legitimate pain needs,

- those who began with valid prescriptions but slid into misuse, and

- individuals seeking opioids purely for recreational highs, without initial pain.

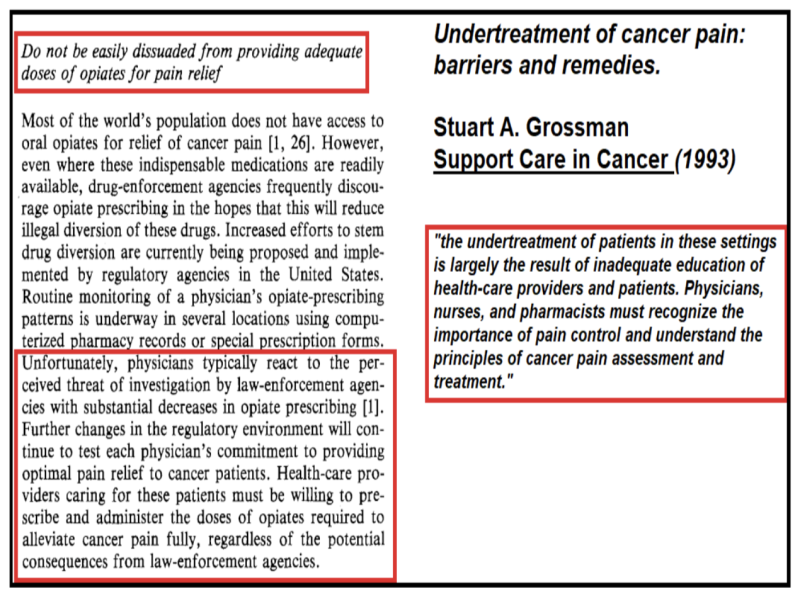

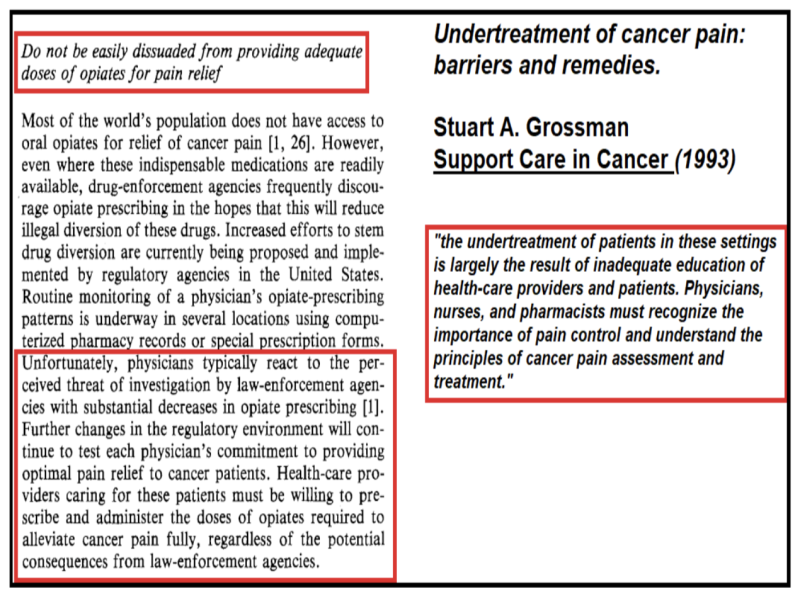

Studies at the time (1990s) pointed to an under-treatment of pain, especially chronic pain, as many doctors were cautious about prescribing narcotics.

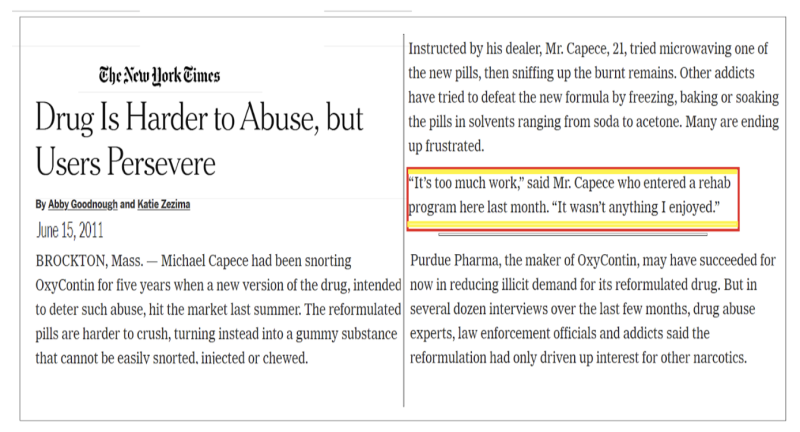

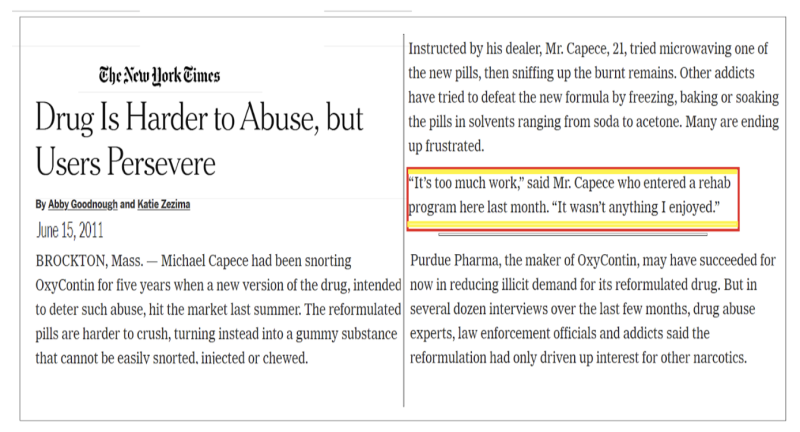

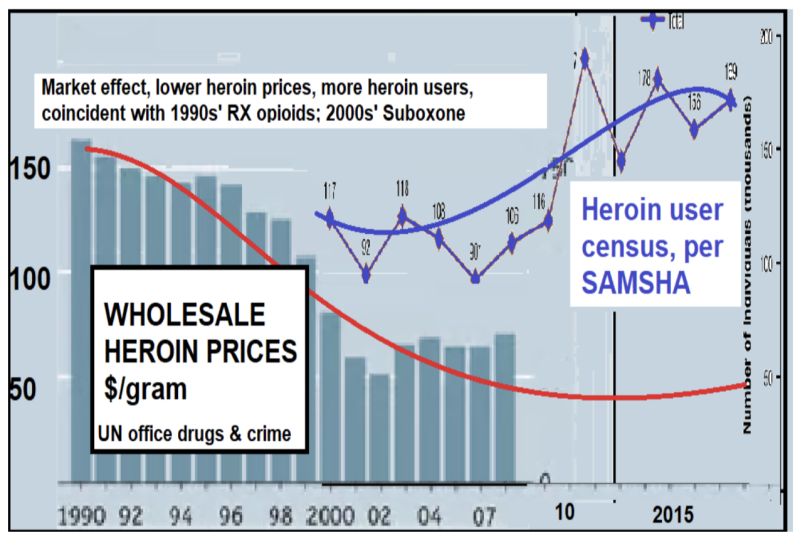

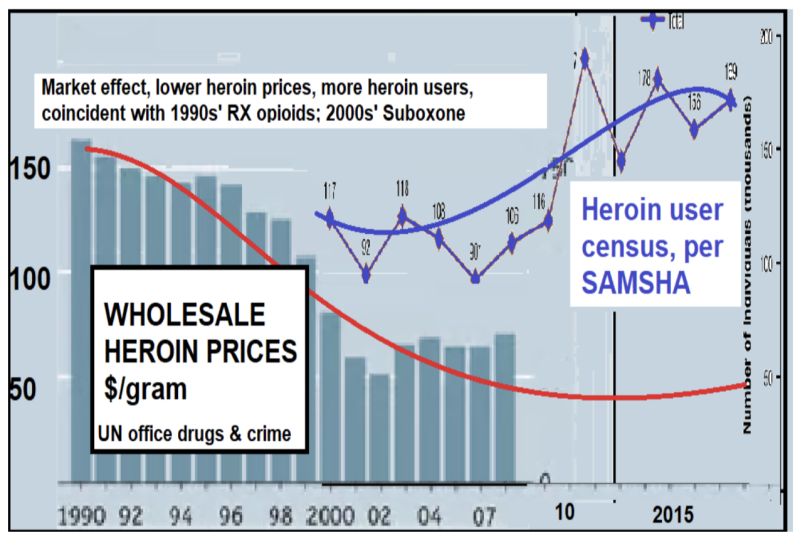

Purdue’s OxyContin sought to address this need with a time-release formula aimed at reducing abuse. One “recreational” user noted, “Most people that I know don’t use OxyContin (II) to get high anymore. They have moved on to heroin.” Among those using opioids to “get high,” OxyContin use dropped while heroin use nearly doubled. According to Theodore Cicero et al. (2012), “Of all opioids used to get high in the past 30 days, OxyContin use fell…whereas heroin use nearly doubled.” The abuse-deterrent formula successfully curbed misuse of OxyContin…

…notwithstanding intrepid Times reporters’ tips for solo “users.”

Purdue’s Historically Contingent Marketing

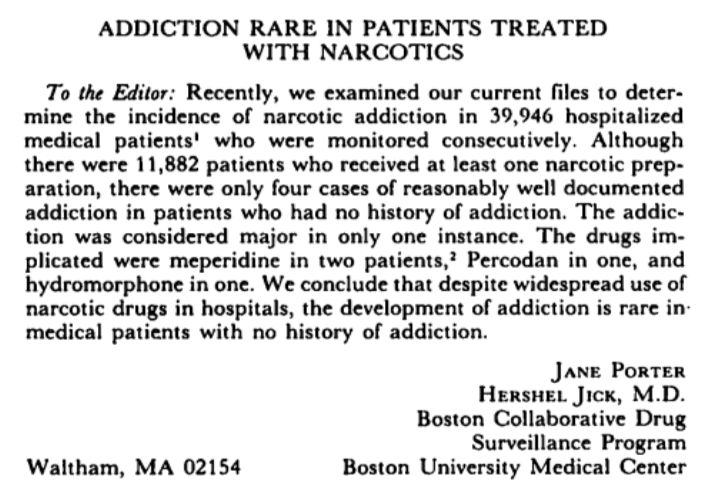

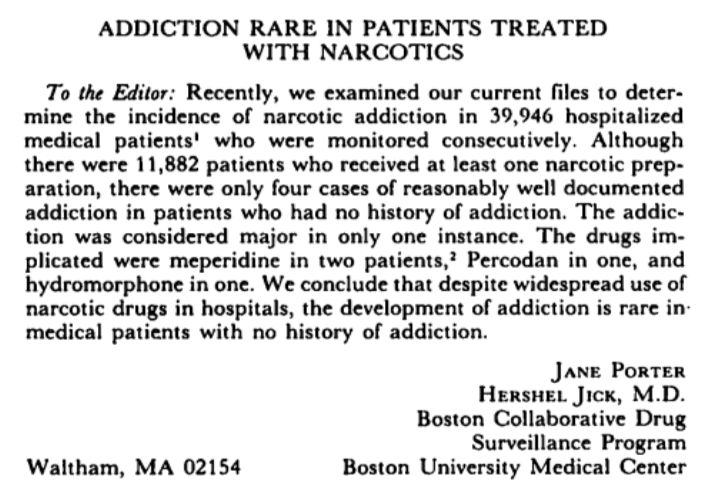

Purdue’s marketing efforts relied heavily on studies that suggested addiction was a minimal risk when opioids were used properly for pain management. A now infamous reference was this 1980 letter to the New England Journal of Medicine that claimed the addiction risk for patients with no history of drug abuse was less than 1%.

While later criticized, this study and others like it (as incorporated into the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Pain’s 1987 report “Pain and Disability… Perspectives”) helped push Purdue (and medicine in general) towards the idea that opioids could be safely prescribed for conditions that had traditionally been treated with more caution or left untreated.

Purdue Pharma’s target audience for OxyContin was never the “addict” demographic but those unfortunates in genuine physical pain via illness or injury.

Purdue positioned (and informed) these patients as distinct from recreational drug users, emphasizing that if doctors monitored prescriptions properly, addiction risk would remain low. And Purdue wasn’t necessarily wrong. Critics argue that it downplayed addiction risks and blurred the line between medical and recreational use; yet, like yesteryear’s slavery and today’s sexual identity surgeries, Purdue’s approach reflected its own time: a healthcare landscape that saw pain relief as an urgent need.

Just as law enforcement and personal safety rely on firearms, opioids retain their essential role in pain management — even if risks of criminal elements’ abuse persist and overshadow the valid use of such tools. To fault Purdue alone misses the broader, unresolved challenge: balancing legitimate medical need with the risk of dependency. The divide between therapeutic and illicit opioid use is not Purdue’s creation but a societal dilemma yet to be fully addressed.

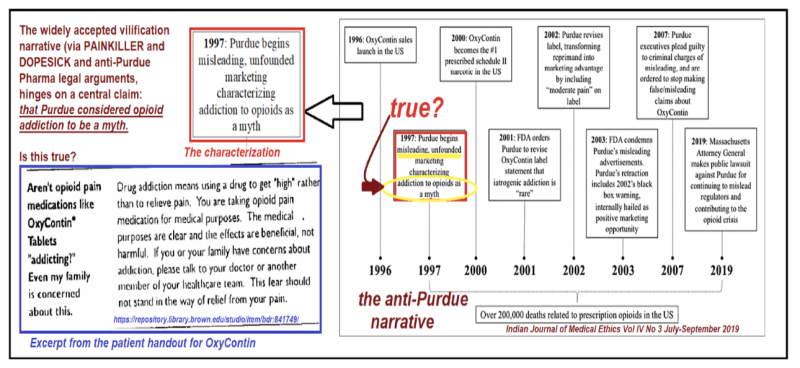

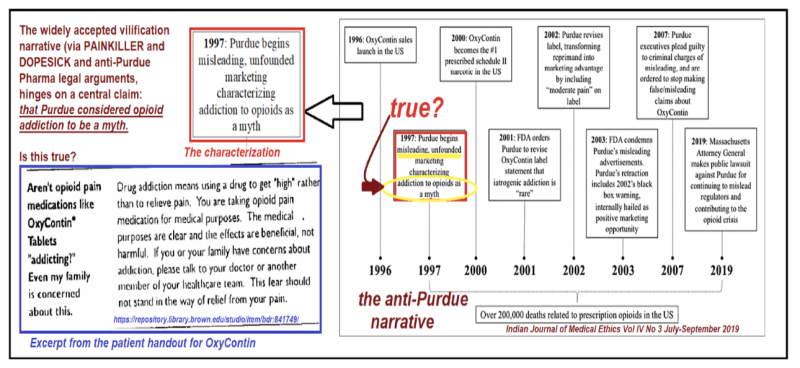

This chart highlights the assumptions that underlie the anti-Purdue narrative—particularly the claim that Purdue misled the public by downplaying opioid addiction risks (see red boxes, below). These critics interpret Purdue with hindsight bias. The actual language used in Purdue’s educational materials, as shown at left, acknowledges risks without advocating misuse. Promoting condom use does not endorse sexual violence; Purdue’s focus on legitimate pain doesn’t encourage opioid diversion.

When Intent Meets Reality: The Emergence of Pill Mills and Prescription Abuse

The flaw in Purdue’s model wasn’t so much in its initial intent, but in what happened once OxyContin entered the broader healthcare system and the market. In theory, physicians were meant to monitor patients closely, ensuring that prescriptions were used for legitimate purposes. But in practice, the system became ripe for exploitation. Certain physicians, driven by financial incentive or indifference, began overprescribing the drug. “Pill mills” sprung up across the country, where doctors would write prescriptions for wholesale doses of OxyContin with little medical justification or interaction.

As a primary-care physician, I witnessed patients coming into my office claiming “allergies” (sic) to lower-dose opioid medications (like Percocet), in an effort to obtain more potent OxyContin. The black market for OxyContin flourished, eventually settling at ~$1 per gram. The flow of OxyContin buoyed by “fifth vital sign” mentality created a leaner, more competitive landscape for narcotics. Heroin dealers adapted by lowering prices and expanding their “customer” base of “users.”

The Bigger Picture: Is Purdue the Real Smoking Gun?

“Because that’s where the money is.”

(why Willie Sutton robbed banks)

Through high-dosage methadone maintenance, the government itself normalized opioid dependency, creating fertile ground for heroin dealers—independent actors as ineradicable as mosquitoes. Government-financed replacement narcotics daily deliver eight times the “high” of peak OxyContin.

Purdue’s fixed resources and corporate visibility made it a prime target for legal action. This approach mirrors past lawsuits against the tobacco industry, and even the gun industry, where the company that provides the legal, adult-only item—whether a smoke or a firearm—became the focal point of litigation, regardless of misuse by end-users. In fact, many of the same lawyers who targeted Big Tobacco adopted the same legal tactics against Purdue, casting the company as the public face of a multifaceted epidemic. Notably, pornographers and sex workers; marijuana and psychedelic dealers (many operating illegally) avoid these strong-arm tactics.

Financial motives drive this selective focus. The NFL, despite not having the highest concussion rates—sports like cycling, snowboarding, and gymnastics surpass it in injury frequency—was targeted for its deep pockets. Like the Sacklers, the NFL was forced to pay out billions for the harm linked to its product. But unlike the Sacklers, the NFL survives, protected by public affection as ‘America’s game.’ The Sacklers had no such goodwill; even the universities and museums that gladly took their donations had no qualms about cutting ties and erasing the family name (with the exception of Harvard!) while conveniently keeping the funds.

The Sacklers were sacked, their assets and reputations torched, much like cities sacrificed to BLM sentiments. Fickle society: are we addressing real issues—or just picking socially acceptable targets to burn?

Like a goose fattened by policies encouraging opioid access, Purdue was plump with profits when the state carved out its liver—a pâté de foie gras feast of settlements—while leaving the deeper, systemic issues it helped create untouched.

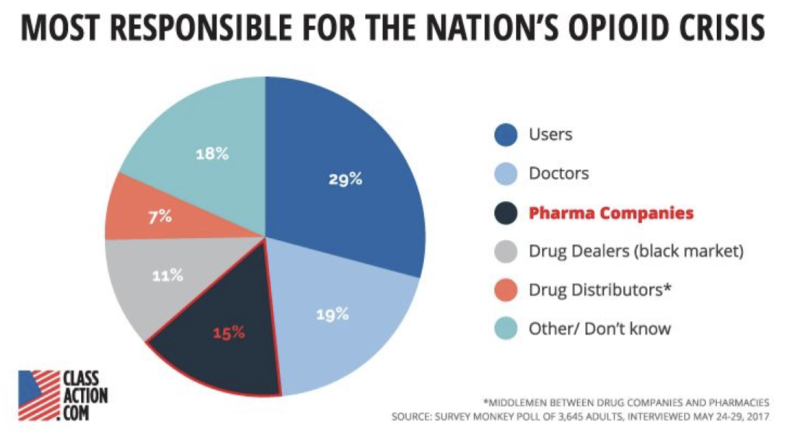

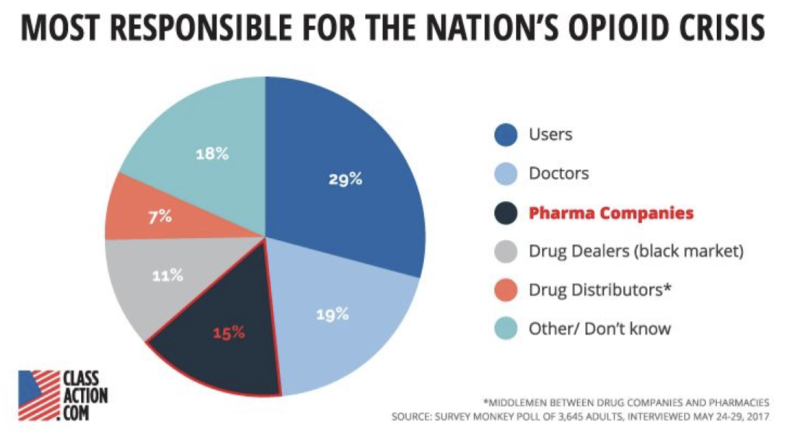

Addendum, QUIZ: which entity is missing in the public imagination as an opioid epidemic causative agent? See this Fortune magazine 2017 poll, via classaction.com.

The opioid epidemic exploded one-hundredfold with the unprecedented introduction of narcotic maintenance “therapy,” methadone—an approach never applied to other addictions like alcohol, cocaine, gambling, or sex.

This unique exception, rooted in the medical profession’s ability to prescribe and profit, reveals a troubling partnership between government policy and corporate gain. Just as taxpayer-funded research paved the way for the Covid-19 pandemic through gain-of-function experiments in Wuhan, the government’s blind spot—or complicity—in fostering addiction treatment models fueled by profit underscores its failure to protect its citizens. When the government errs, it doesn’t just fail—it enables catastrophe.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.