History Repeated: Forgotten Lessons of Narcotic Substitution

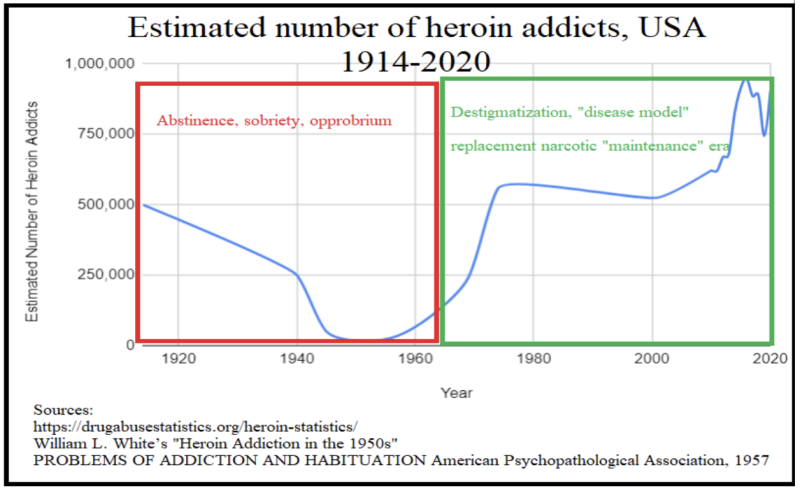

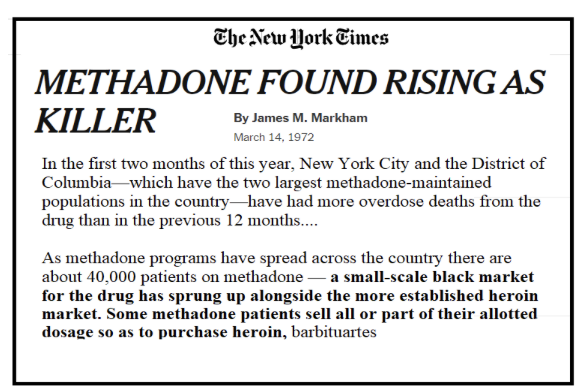

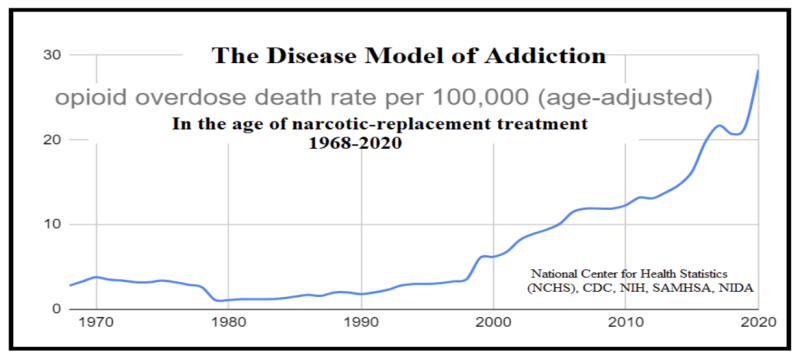

In the shadow of the Netflix series Painkiller, combined with OxyContin documentaries—and the plague of fentanyl overdoses—lies an obscured chapter of America’s opioid epidemic: the 1965 “invention” of “Methadone Maintenance Treatment” (MMT) at Rockefeller University. Its immediately forceful promulgation by the public health establishment multiplied tenfold (!), within a decade, the nation’s number of narcotic-addicted souls.

This vast expansion of methadone use created the metaphorical ‘fertile soil’—within which the later, more notorious vines of the opioid crisis took root and thrived. Certainly, aggressive marketing of Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin and the influx of fentanyl from China (via Mexico) accelerated opioid death rates these last few decades, but the paradigm shift from detoxification to maintenance did it first.

The decades immediately prior, 1923 to 1965—in Prof. David Courtwright’s view, the “classic era of narcotic control; ‘classic’ in the sense of simple, consistent, and rigid”—had brought the reverse, a steep decline in drug abuse. Sobriety, abstinence, and societal disapproval formed the pillars of what had been an enormously successful de-addiction strategy (from the opium, morphine, and heroin addictions of the early 1900s).

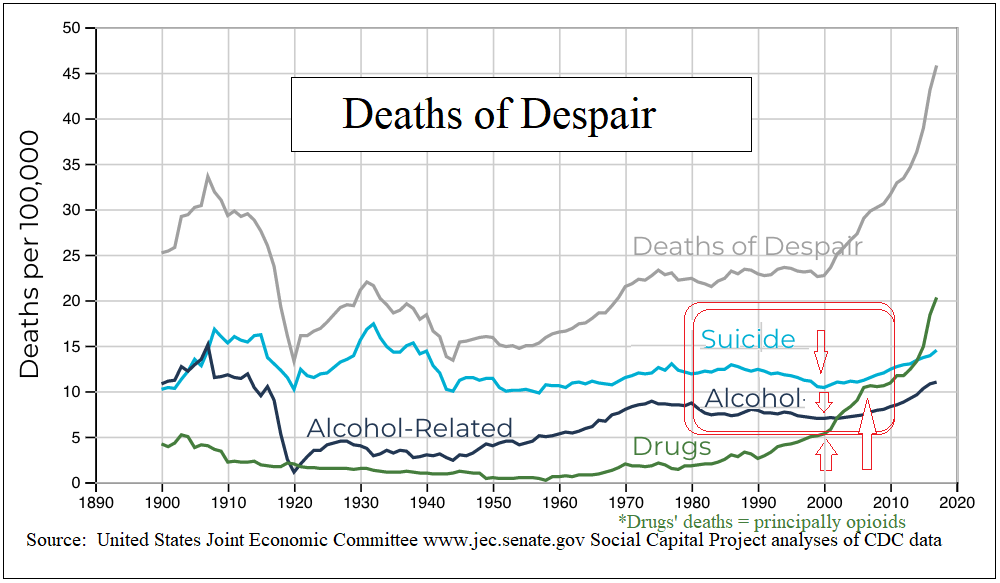

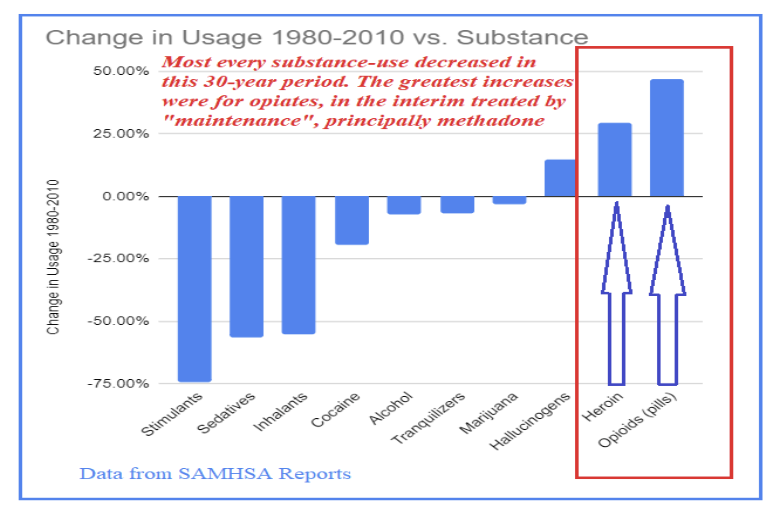

The decades immediately after, within “The Long Boom” (1980-2010), represent the United States’ longest continuous era of prosperity. So-called “deaths of despair” diminished nearly across the board. There were fewer suicides, and deaths by alcohol and drug abuse of every kind declined—except for opioids, the only drug class to have been “medicalized.”

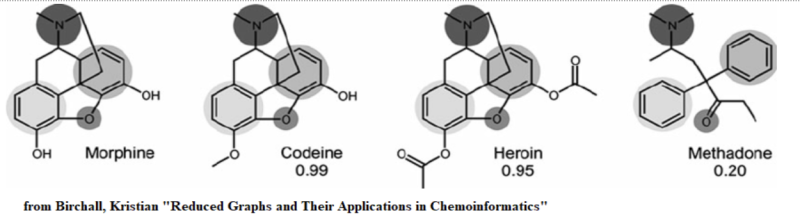

The newly adapted and widely adopted “Disease Model of Addiction” soon analogized narcotics’ methadone with diabetics’ insulin as both requiring long-term “replacement” medication—however, for any similar “disease” of addiction to tranquilizers, cocaine, alcohol, or barbiturates—abstinence (antithetically and hypocritically) remained the endgame. It remains notable that to this day not a single ardent advocate of the Disease Model supports maintaining people on benzodiazepines or cocaine. This glaring contrast cannot be unseen.

This medicalization of opioid addiction, while distinct and perhaps well-intentioned, seems to have backfired decades ago already. Instead of curtailing use, it has fostered an environment where opioid reliance has flourished, outpacing other substances during America’s most prosperous years. This has cast methadone not only as a tool for treatment but also as a potential contributor to the very opiate problem it sought to mitigate.

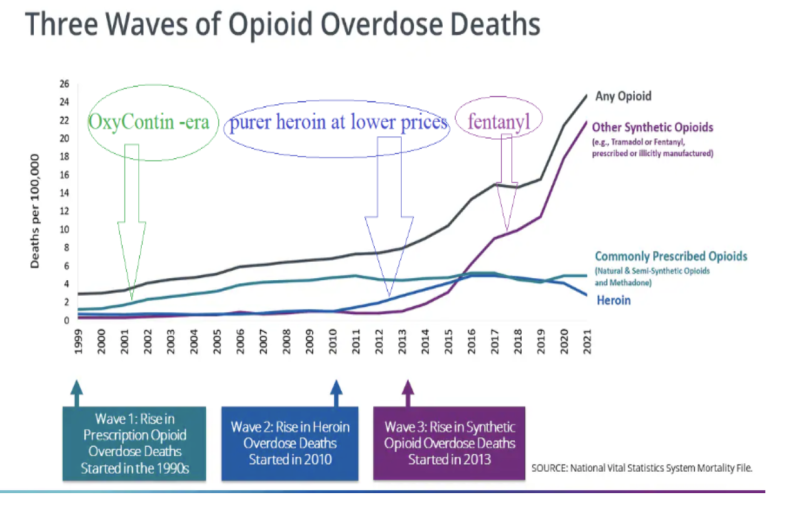

The CDC’s opioid epidemic timeline charts three “waves” (or ever-rising tides) of opioid deaths. It starts with OxyContin, moves through cheaper heroin’s greater reach, and peaks with fentanyl’s deadly surge.

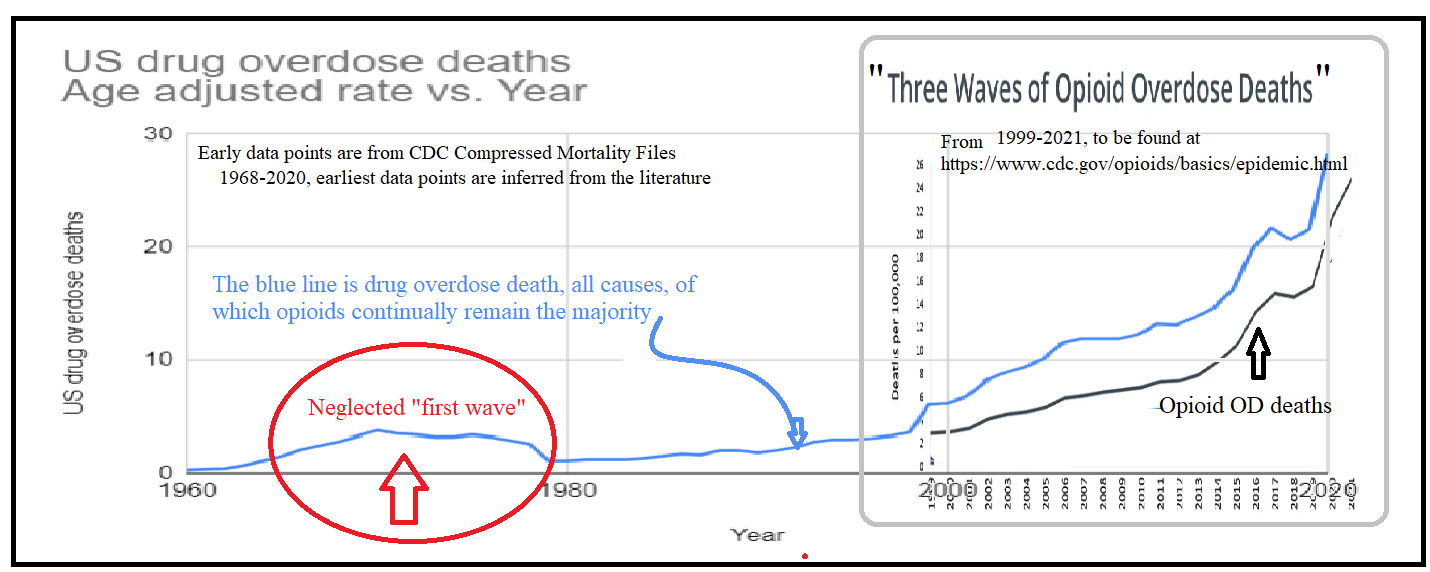

What the CDC’s graph doesn’t show is the prelude, methadone’s neglected, silent swell in the ’70s, a tide that raised all boats, lifting the numbers of those physically bound to opioids long before the CDC’s “Wave 1” (sic) hit.

This next, grander timeline contextualizes this methadone “first wave,” by reaching back to 1914. The 19th century’s taste for raw opium had been superseded by the use of its congener, morphine, (often with the latter’s “treating” addiction to the former)—with predictable results: a new morphine addiction. By the turn of the century, heroin (a.k.a. diacetylmorphine) entered as a similar would-be savior to morphine’s menace, only to become a larger problem itself: half a million heroin addicts (amongst 100 million Americans). Proportionally in 1914, the scale of the opioid crisis was nearly as vast as it is today; however, unlike the modern situation, the problem steadily declined, effectively reaching zero.

In the 1920s, America took a firm stance against opiates, a move that coincided with a period of economic growth and cultural dynamism. The Roaring Twenties were defined by prosperity and progress (and yes, Prohibition), with the nation’s collective focus turned toward innovation and recovery in the post-war era rather than the haze of narcotic addiction. The clear-cut policies of the time, emphasizing sobriety and lawfulness, contributed to a society poised for the demands and victories of the coming war years. It was a time when the choice for health and productivity was clear, and the shadow of heroin receded in the wake of national ambition.

Defiance of historical lessons brought methadone to the forefront of heroin addiction treatment—a deliberate pivot from the proven, ongoing strategies. 1960s-70s health policymakers embraced opioid methadone as MMT, mimicking the old, futile cycle of using one opioid to combat another.

Naturally, this stark reversal was clothed in contemporary scientific lingo, with MMT’s inventors coining and claiming a “metabolic theory of addiction.” Nonetheless, it was a willful spurning of the erstwhile national ethos of resilience and personal responsibility that had successfully reduced the number of opioid deaths to almost zero—setting in motion the enduring opioid crisis we grapple with today that now kills 100,000 Americans every year, almost double the toll of the entire Vietnam War.

Local Crisis, National Response: Methadone’s Misguided Expansion

When France sneezes, the whole of Europe catches a cold.

Metternich, 1848

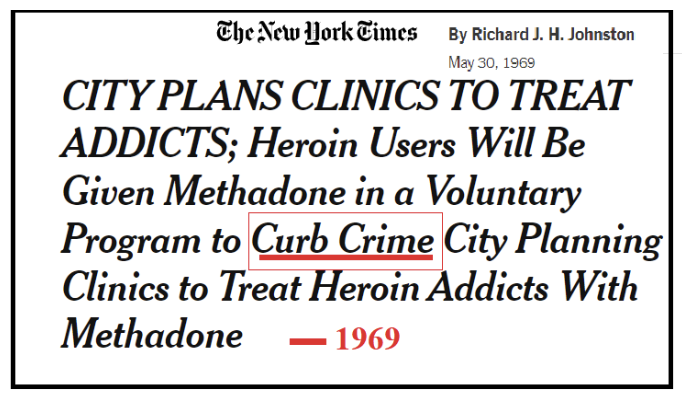

In 1966, the nation’s first methadone clinic emerged (physically and conceptually) from within New York City’s unique situation: with its addiction rates 25 times higher than the rest of the country. The city’s dense urban pathways facilitated a desperate flow from impoverished neighborhoods like Harlem to wealthier districts, fueling thefts to fund drug habits. The city’s solution? Methadone.

Methadone was less about recovery than social sedative: prescribed for upper-class comfort rather than lower-class addicts’ long-term benefit, reflecting a stark shift from faith in recovery to resigned management of symptoms. The Elites decided to keep the Masses pacified. Templating a New York City -problem nationwide played out similarly during Covid-19. Dense, polyglot NYC-borough Queens’ severe (but outlier) inaugural outbreak led to overreactive restrictions applied everywhere else–(then, as previously) fanned by the New York Times’ own viral reach. Nineteen-sixties-era New York Times’ broadly favoring methadone similarly shaped policies nationally, albeit it was perceived as having done so parochially.

Broken Promises, Methadone’s Failure: More Crime AND More Addiction

Let’s set the scene: 1960s’ New York, America’s thriving hub of commerce and culture—albeit with stark socioeconomic and racial divides, faced a social challenge due to heroin addicts principally in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

From William L. White’s Heroin Addiction in the 1950s: “The trend of increased heroin use in poor African American and Latino communities that had begun before WWII continued. Actually, heroin was in the same neighborhoods it had always been in, but who lived in those neighborhoods had changed...[and crucially…]Addiction, as William Burroughs once noted, is a ‘disease of exposure,‘ and those being exposed in the 1950s changed as neighborhoods changed.”

Heroin addiction at the time was far from a national problem. New York City’s relatively small number, ~17,000 individuals, nonetheless comprised fully half of the nation’s heroin addicts (with only 4% of the US population). White continues:

Narcotic addiction had so dramatically declined during World War II that the Bureau of Narcotics planned to make a final push of intensified enforcement to eliminate America’s drug problem. The Bureau continued to boast in the 1950s that the number of narcotic addicts in the U.S. had shrunk to its lowest level in modern history…from 500,000 in 1914, to 250,000 before World War II and to an all-time low estimate of 34,729 (nationwide) [about 1% of today’s cohort].

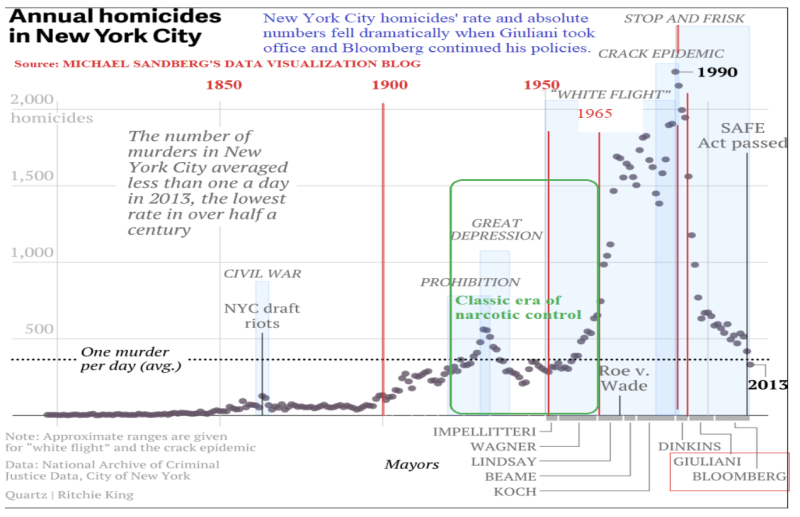

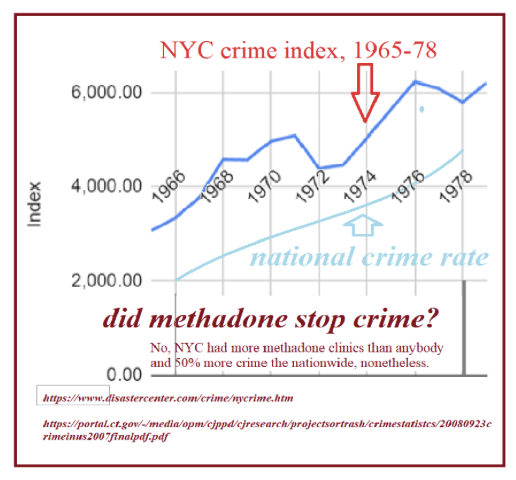

This “classic era” of narcotics control was reflected as well in low crime, and a low homicide rate (as pictured below); (NB: NYC’s population was reasonably static 1930-1990). Certainly numbers were going up in the early 1960s, but no higher than in the 1930s Great Depression. It wasn’t a matter of “drastic times require drastic measures” until after a drastic measure (the policy reversal with MMT) exploded the homicide rate, see 1990’s. Progressives (definitionally) “look forward,” and abjured the disciplines and disciplinary measures that had brought the previous peak down.

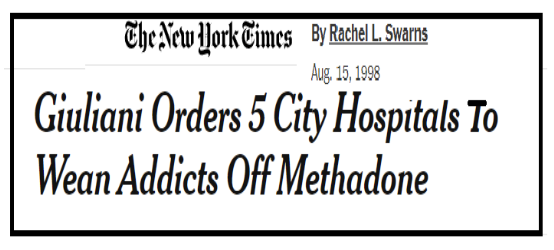

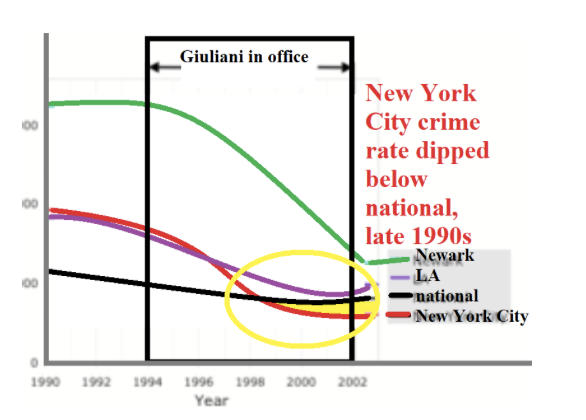

Even at this era’s Great Depression peak, homicides were four times lower than in the 1990’s, 20 years into the methadone era. Conversely, the 35 years pre-MMT were a period of relative calm, with homicide rates low. Correlation is not causation, but there’s a massive uptick in homicides coinciding with MMT-expansion. The ’90s show a dramatic decline, correlating with stricter law enforcement under Giuliani (who did all he could to stop city sponsorship of MMT) and Bloomberg.

Post-de Blasio, again there is a surge in crime. It’s fair to say that methadone, though lingering as a historical “fix” (pun intended), completely failed to tackle the very issue against which it was deployed. The data suggest that both narcotics policy and the underlying social directives influence crime rates. The numbers are real, and give us a clear message that advocates of the Disease Model choose to ignore.

In the early 1960s, New York City’s crime rate ascended, maintaining a steady 50% surplus over the national average. No doubt, it was fueled by the nation’s highest heroin addiction rate and attendant theft. So, the crime-“diagnosis” was correct, but the MMT “cure” (akin to “more leeches”) was likely the cause, and sticking with it only aggravated the underlying narcotic issue, increasing the cohort of users, crime, and deaths. Contrastingly, Giuliani cut crime in half with “broken windows”-policing, dropping New York City BELOW the national average.

In 1970, Dr. Robert Baird of Harlem’s “Help Addicts Voluntarily End Narcotics” sensed this, predicting a methadone-blowback/-debacle:

Methadone is no major breakthrough; it’s a major breakdown. There’s absolutely no difference in substituting methadone for heroin; the end result is the same—you have an individual who is addicted. It’s (been on the streets) since 1945; the kids in Harlem call them ‘dollies’.

For the methadone recipients, a binary formed: stick to the maintenance or sell the dose, an illicit windfall—that created new “proxy” narcotic dealers. The original dealers, far from abandoning their trade, simply expanded their turf. Methadone, intended as a societal salve, instead became a market force, pushing heroin into new territories.

For the methadone-“donors,” safely perched at universities and hospitals, providing a newly-legal substitute for heroin was akin to the contemporary compassionate act of shaving one’s head in solidarity with a cancer patient. However, unlike that uplifting gesture which doesn’t change any medical reality, the methadone program spread the “cancer” of drug use, bringing larger numbers across a broader spectrum of society down to a new level of dependency, and total loss of agency over their lives, tethered as they are to the daily trek to the methadone clinic every morning, being observed to actually consume the drug, and being randomly drug-tested. Methadone patients are not intended by Disease Model advocates to be independent individuals ever again for the rest of their natural lives.

Equality of Misery: Methadone Didn’t Fix Harlem, It Spread the Despair

Echoing Winston Churchill’s critique of socialism—“The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings. The inherent virtue of Socialism is the equal sharing of miseries”—the adoption of methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) created this latter “equality.”

At the risk of having one too many shaved-head analogies, this brings to mind a joke:

A balding man offers $1,000 to have his head look “just like” his hirsute barber’s. The barber proceeds to shave both their heads, completely—making them equally bald, and pockets the cash. The customer is less than thrilled.

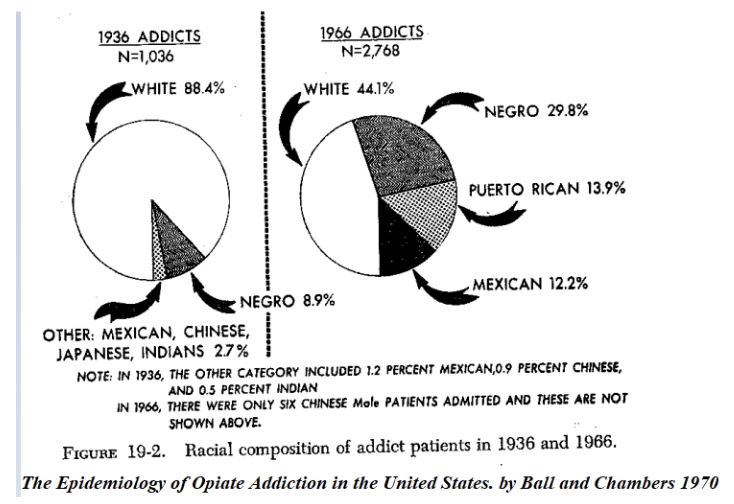

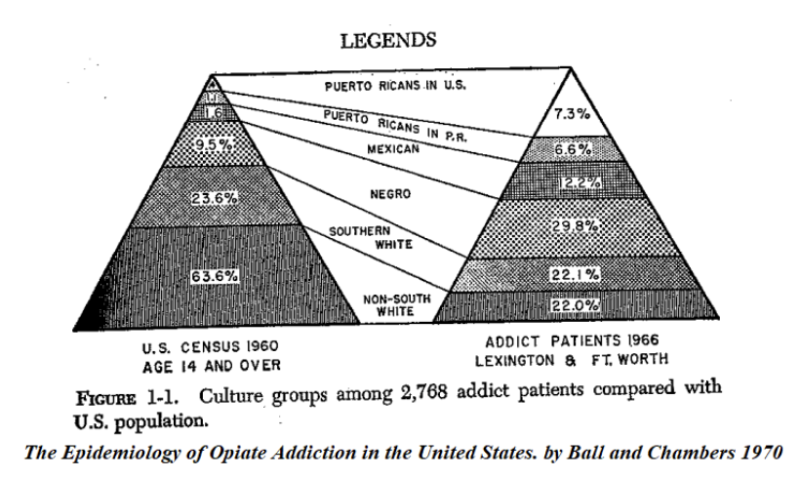

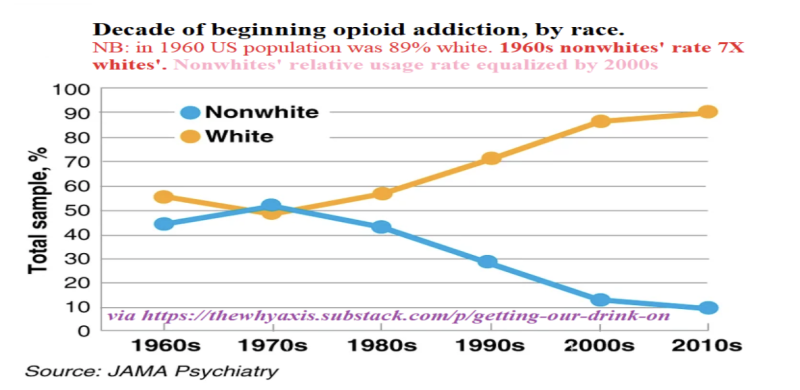

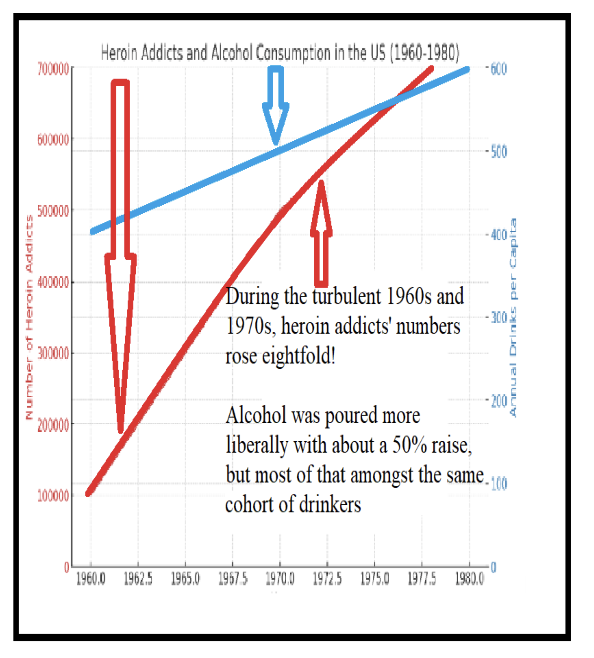

Similarly, methadone maintenance, sold as the medical scientific fix to Harlem’s heroin problem, just spread the misery uniformly nationwide, without truly solving the underlying issue. In 1960, Blacks were seven times more likely to take up heroin. Fifty years later, whites were equally likely as nonwhites. In the meanwhile the total number of addicts had grown 25 times higher.

The resulting industry—here only partially tongue-in-cheek called, “The Methadone Industrial Complex” (MIC)—had, even in its nascent stages, vastly favorable PR, via the local New York Times, public health leaders, and intellectuals. As with Covid-19, decisions were made centrally, federally with ramifications and repercussions rippling outward. The late 1960s saw some additional methadone clinics, but their number vastly proliferated in the early 1970s under federal rules’ relaxation and the passage by Nixon of his 1970 Controlled Substance Act which created a massive federal bureaucracy that superseded state-level health care decisions.

In April 1971, the FDA reclassified methadone from an “investigative new drug” to a “new drug application,” significantly broadening its use. This change scrapped critical safeguards, notably the prohibition against prescribing to pregnant women, resulting in their inability to protect their own newborn babies from the very same narcotic-withdrawal symptoms methadone-prescribers deemed too difficult for the moms to endure. This remains a cruel side effect of policy loosened under the guise of accessibility because addiction (ostensibly) is a disease that needs ongoing treatment.

The most critical shift, however, was the removal of dosage- and treatment-duration caps. This effectively institutionalized and perpetuated patient dependency, transforming methadone treatment into a relentless lifetime subscription model. This model, sustained by regulatory support and licensure, guarantees methadone clinics a sinecure: contributing to an eternally-profitable “methadone industrial complex”—that thrives on sustaining addiction rather than curing it. Their “customers” are forced to keep them in business by the government and the courts.

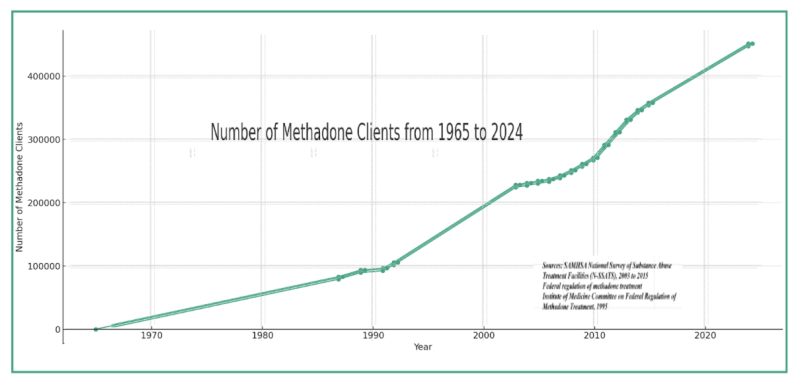

As reflected in the graph below, these relaxed regulations led to an exponential growth in methadone patients—from 9,100 in 1971 to as many as 85,000 by 1973—setting in motion a ‘first wave’ of opioid dependence that foreshadowed later surges.

Framed as a public health solution, methadone clinics, particularly in New York City, grew akin to a “Starbucks for opioids:” perpetuating addiction ensured steady revenue from federal and local funds, despite early warning signs and community resistance.

Mr. Austin said he:

“shuddered to think of the problem East Harlem would face if heroin were made as freely available as methadone.” Mrs. Mildred Brown, chairman of the community board: “One maintenance program wanted to come in and bring 500 addicts with it. I said East Harlem has enough addicts of our own, we don’t need to import any. We have to approach each addict as a human being and find out what motivates his addiction and change it.”

METHADONE PLANS SCORED IN HARLEM April 23, 1972

“Harm Reduction”

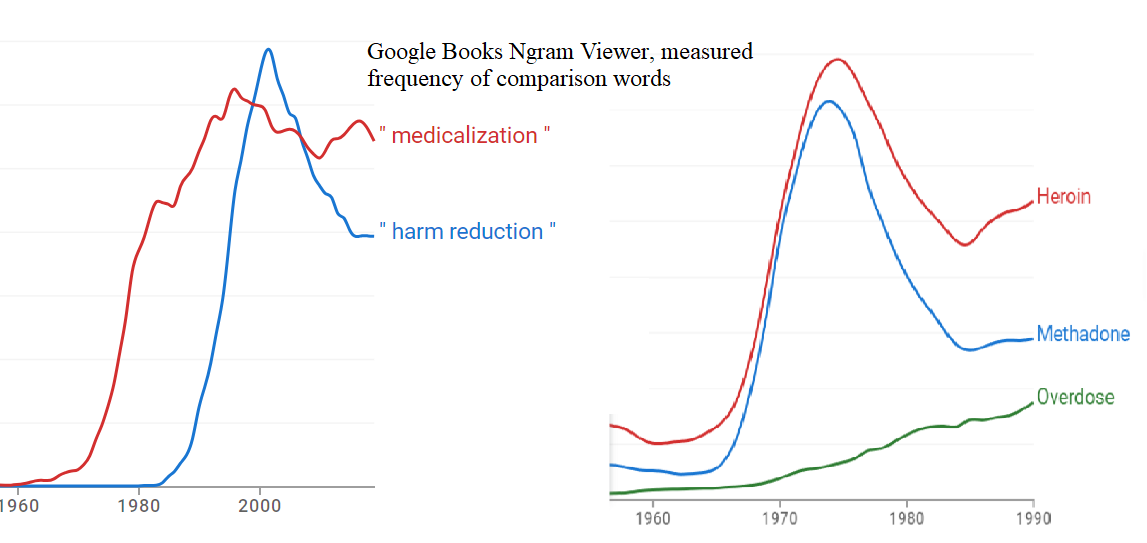

Without getting ahead of ourselves, it’s crucial to draw parallels between the MMTs initiated in the late 1960s and the needle exchanges that came later, both emerging as intellectual elite-generated solutions purportedly aimed at the underclass. MMT-rationale fell under the rubric, “medicalization.” Arguably, this is the precursor to the term “harm reduction”. Here is a Google Ngram marking the literary frequency of the terms (along with another implying methadone’s aiding rather than stymieing heroin use within a similar time frame).

The late-1980s (HIV/AIDS -era) genesis of needle exchanges fell under the term “Harm Reduction”—a term as agreeable as ‘affordable housing‘ and “improving access to care” making disagreement seem taboo. And indeed, we prefer our needles clean; yet, these broadcast acceptance of bad behavior. Needles in pharmacies and condoms in middle schools are endorsements erosive to personal responsibility and inner discipline. Removing consequences doesn’t cultivate prudence. In addition, providing needles or “safe injection sites” is entirely unnecessary given that heroin is simply morphine which is still available in safe pharma-grade pills through a doctor’s prescription.

Such strategies invariably magnify the problems they seek to address.

In 1988, the New York City Council’s Black and Hispanic Caucus warned of needle exchanges:

It is beyond all human reason and common sense for the city to hand out needles to drug addicts when police and citizens have become casualties in the drug war.

These policies were imposed on communities whose actual needs and circumstances are vastly different from those of the policymakers, who tell themselves they know better as they are better educated, scientific, and have the burden to “uplift” the great unwashed. The underclass, often most affected by such policies, finds their voices and preferences overridden by a top-down approach that does not align with their lived experiences.

Harm reduction strategies are steeped in a pragmatism that some critics argue borders on defeatism. Conversely, abstinence is an approach that challenges individuals to rise above their circumstances, advocating for individual empowerment over mere management. Striving for abstinence is a bit like Churchill’s view on capitalism’s regretted “unequal sharing of blessings:” fraught with disparities in success.

Just as quitting smoking is a task some jest to have mastered many times over, failing sobriety doesn’t negate the possibility of eventual success. The “classic era’s” emphasis on individual strength and perseverance led to near-zero opiate use; today’s permissive stance sees higher addiction rates than ever, with the consequences of this lenience proving more fatal than car accidents, which at least occur when trying to go “somewhere” as opposed to “nowhere.”

During the cultural shifts of the ’60s and ’70s, alcohol consumption increased yet the number of drinkers remained stable, and the fatalities did not surge. Bartenders, though dispensers of spirits, didn’t see their patrons’ numbers swell as clinics have seen opioid users multiply. They might envy physicians for their ability to have created such a captive market (driven by medical-legal sanction rather than consumer choice). It’s instructive as we ask the question “Who are the ultimate beneficiaries of this medicalized approach to addiction?” to look at the “medicalized” marginalized. Please see this excellent photo essay, 2016: “LIFE AND LOSS ON METHADONE MILE”.

Market Flood: Prescribed Narcotics Drive Down Heroin Prices

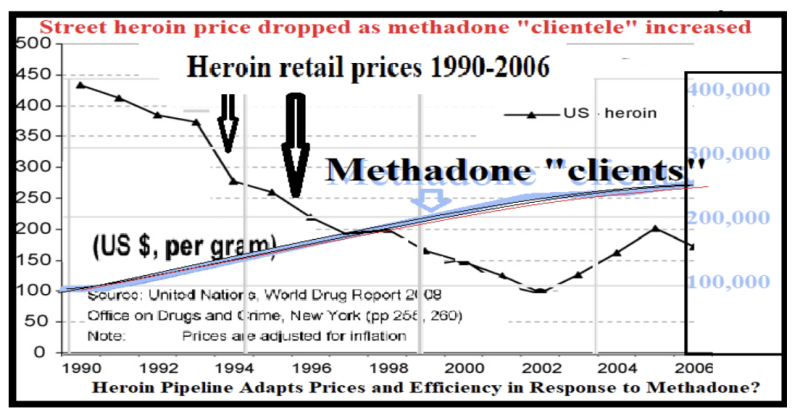

As methadone clinics proliferated, organized crime—axiomatically, both criminal and organized—adapted. Heroin dealers, faced with dwindling customer bases, did not recede (or become accountants and travel agents); they branched out, targeting younger demographics and untapped neighborhoods with lower prices. We see both aspects in these two quotes:

New heroin users include adolescents in ever-increasing numbers. In 1988 the mean age of heroin use in the United States was 27; in 1995, the mean age of self-reported heroin use was reduced to 19 years.

Adolescent heroin use: a review, 1998

Heroin use is skyrocketing among middle class, suburban teens…Since 2002, initiations to heroin have increased 80 percent among 12- to 17-year-olds.

2012

Government intervention flooded the market with methadone, lowering heroin prices. As Adam Smith might observe, lower prices inevitably attract more users. Moreover, every methadone user remained perpetually susceptible to immediate re-addiction.

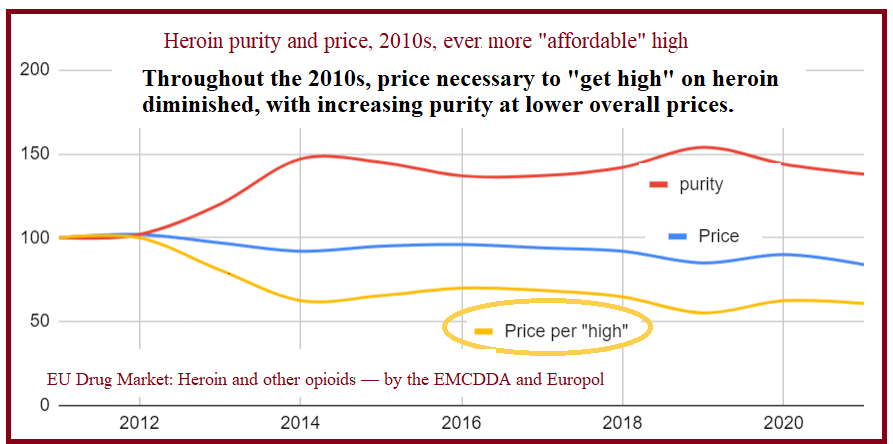

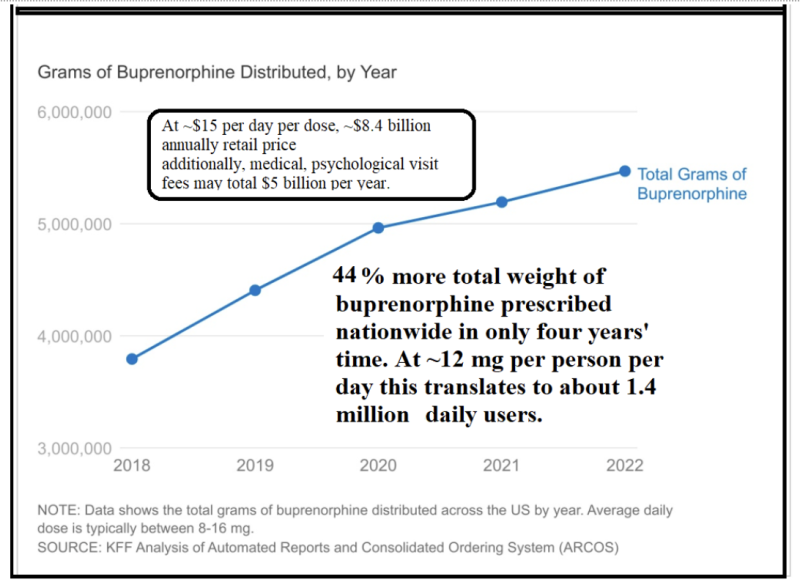

“Wave 2” of the 2000s opioid crisis mirrored this earlier pattern: its “purer heroin at lower prices” coincided with the introduction of Suboxone. This shift followed the 2000 Drug Abuse Treatment Act (DATA), which added buprenorphine—a less sedating opioid—to the medical arsenal against addiction, aiming to reduce the stigma of treatment seen in methadone clinics; while ironically underscoring the shortcomings of its predecessor.

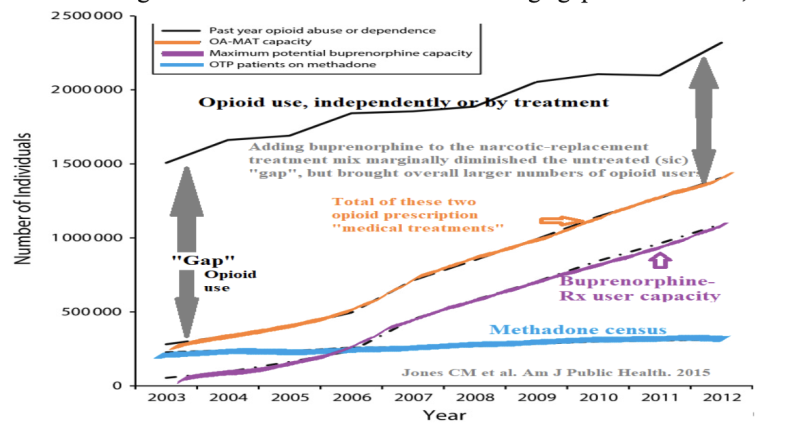

The first decade of Suboxone saw a growth even more rapid than methadone’s, from zero to a million users. The subsequent decade brought a 50% further increase to ~1.5 million current users. And all this without a notable decline in methadone “-census.” Once again despite all this additional “treatment” of the “disease” it’s a bit like a dog’s chasing its tail. Ever elusive is the “goal” as the overall independent “nontreated” opioid user account always exceeds the amount that we are giving in treatment. Has there ever been any other disease whose untreated users expand the more we treat the others? The only example would be once again the medieval “more leeches” example of bloodletting to cure fatigue.

The following chart shows that there is a diminishing “gap” in “untreated,” independent opioid use; but this “Suboxone-decade” saw a 50% overall increase in opioid usage. There were a million brand-new users of buprenorphine, and around 850,000 more use of opiates/opioids in general. And, if the purpose of buprenorphine was to get methadone users out of their grim surroundings to happier places, medical offices—seemingly, the methadone clinics (and the “MIC”) didn’t seem to have signed on to that: keeping robust numbers, a half-million tethered souls (at $126/week, $3.2 billion/year).

Increasing buprenorphine, yet another governmental opioid added to the mix again coincides with a drop in the effective heroin price (the lowered cost to get high; price/purity). Here’s the European heroin price trend. Europe approved Suboxone in 2006. Our pattern is no doubt similar, sourcing heroin from the same places, and network.

The relentless cycle of opioid treatment echoes the folly of using mercury to treat syphilis in the 19th century, wherein the ‘remedy’ often exacerbated the affliction. In our time, each wave of “treatment” merely swells the ranks of the afflicted, a bitter irony where the cure feeds the disease, spiraling ever out of control.

Cui Bono?

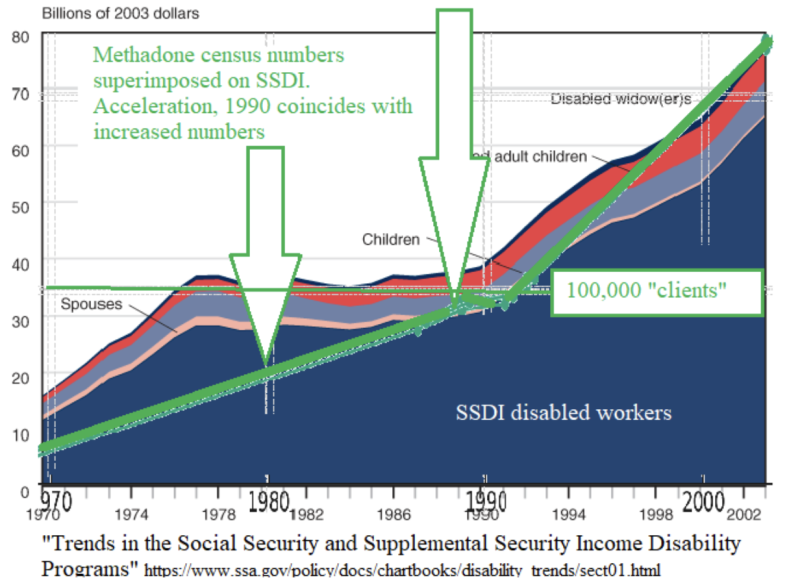

The burgeoning methadone and buprenorphine markets resemble less a medical initiative than an economic one, burgeoning into a $16 billion industry underpinned by taxpayer dollars (via Medicaid and Medicare disbursements). The cost of heroin, methadone, and Suboxone was always higher than the lowly crushed poppy husks, as are their doses. As doses and dependency grow, so too do profits— and the social costs escalate correspondingly. Superimposing contemporaneous methadone census numbers onto Supplemental Security Disability Income data maps a simultaneous doubling of both during the 1990s. Is that a coincidence?

It’s not as if the 1990s were a particularly dangerous time. Again this was during “the long boom” of prosperity coinciding with automation, and greater safety. As comparison, the number of reportable fires went down 50% in that same decade.

Methadone clinics and buprenorphine producers, like Suboxone’s Reckitt Benckiser (now renamed Invidior), have crafted a captive market that thrives without conventional marketing and advertising—through a cycle of chronic treatment imposed by doctors and judges.

The Disease Model of addiction has resulted in two simultaneous expansions: a burgeoning opioid medical industry and escalating opioid-related deaths. This raises a stark question: Are we nurturing a cure, or are we feeding an epidemic?

The Disease Model of Addiction Fails. People Have Souls.

Methadone maintenance was pioneered by the married Drs. Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander along with Dr, Mary Jeanne Kreek at Rockefeller University.

They

…took the perspective that long-term addicts continued to use heroin and repeatedly relapsed to heroin use after detoxification, drug-free treatment, or imprisonment in an attempt to correct a fundamental metabolic imbalance (sic). Whether the imbalance was caused by the drugs themselves, by the person’s genetic endowment, by traumatic developmental and environmental experiences, or some combination of these factors was unknown. Their vision became known as the “metabolic theory.”

Methadone: history, pharmacology, neurobiology, and use; Green, Kellogg and Kreek (herself)

The assertion that addiction stems from a specific metabolic flaw lacks concrete evidence. Humans are addiction-prone (video games, pornography, gambling, cosmetic surgery, steroids, philandering, cocaine, coffee, alcohol—you name it)—making the “disease” label both precarious and recency-biased. How many of these “diseases” did ancient Rome experience?

Conversely, “recovery” implies adaptive resilience more than permanent impairment. Brain scans et al. indicating “changes” during addiction mirror the brain’s response to any profound loss, and importantly, they are reversible. Falling in (and out) of love follows the same patterns, neuro-chemically, etc. Some even want to “treat” the “addiction of love.”

Nonetheless, MMT was seen as a ‘progressive’ solution, aligning with the broader mid-century shift in America where medical technologies were increasingly seen as solutions to social problems. Early methadone providers analogized:

The former addict’s medical dependence on methadone is a parallel to the (type I) diabetic’s dependence on insulin...The disease is not cured but brought under medical control.

(multi-physician) Committee for Expanded Methadone Treatment, 1970

Methadone can’t give you a job, or good manners or make you literate. But for healing the medical symptoms of heroin addiction, (methadone equates with) what insulin is for diabetics.

Dr. Edwin A. Salsitz, director of (NYC’s first and largest MMT program, Beth Israel NY 1997

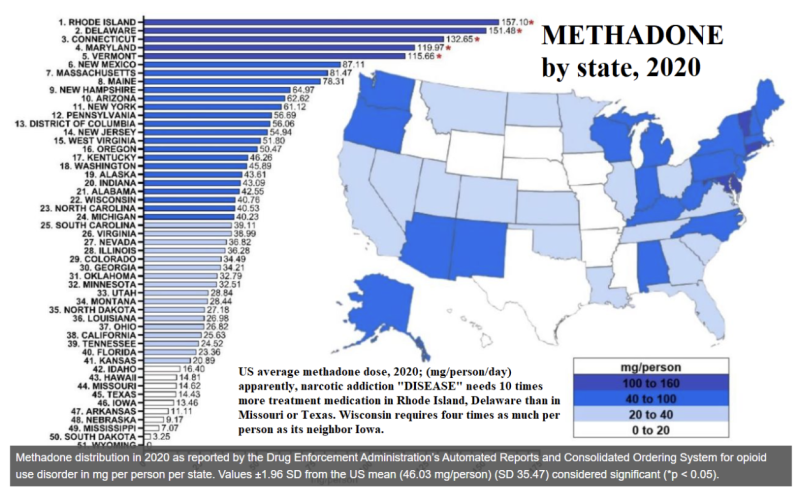

Except that it isn’t! Complete diabetics with no insulin die; heroin addicts (after the trials of withdrawal) flourish. Moreover, the average insulin dose is identical state-by-state—but not so for methadone:

Dr. Kreek lamented that 90% of the world doesn’t get MMT, yet no methadone-free country has magnified its opioid deaths more than the United States, in these last 60 years. The closest competitor would be Russia, yet they have only ~20% of our opioid fatality rate.

Heroin was unknown in the Soviet Union until its troops invaded Afghanistan in 1979 (–so now) Russia has an opioid addiction crisis about as grave as America’s (but) no methadone as replacement therapy. Russian doctors disdain such “soft” treatment. We call a person’s addiction in remission if they are completely drug-free. Not otherwise.

Dr. Morozova is one of the system’s success stories; she credits its “tough love” with curing her of her heroin addiction. But once her three-year program ended, she turned to a linchpin of Western addiction control that has caught on widely in Russia–Narcotics Anonymous. “The 12 steps saved my life,” she says.

(2017)

Rethinking Addiction: If Not a Disease, Then What?

Dr. Mitchell Rosenthal, without a financial stake in MMT (or the MIC) but—to be fair, a competitor at abstinence-directed Phoenix House—stated:

Methadone is a very useful drug for a limited number of people. It has been oversold for a wide number of people. Because many addicts abuse multiple drugs and have limited education and job skills, they are not going to be chemically fixed by giving them another drug.

(1997)

People who come into Phoenix House are essentially strangers to themselves, We give them the support they need to share their destructive secrets, to shed their guilt, to purge their rage, and to unlock their potential.

(2009)

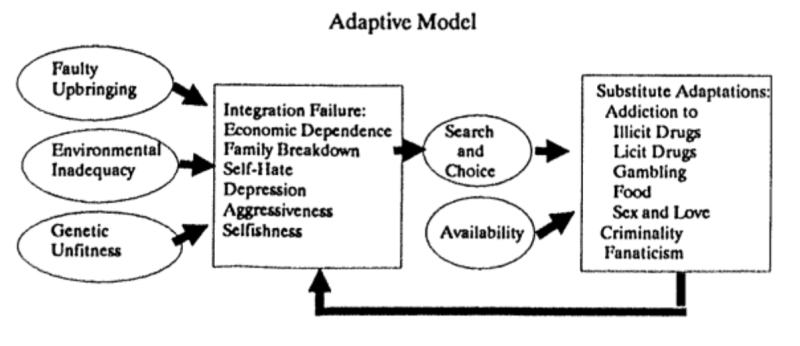

Countering the “Disease Model,” Dr. Rosenthal’s view is in line with the contrary “Adaptive Model” which views addiction as a response to environmental and personal stresses—such as economic hardship, social isolation, or family issues and emphasizes the role of social and psychological interventions. It posits that enhanced coping strategies can effectively address addiction.

For every other substance abuse addiction, the Adaptive Model is operative (although not acknowledged; everything is a “disease”). Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous emphasize personal growth and community support. Members explore their personal challenges and behaviors in a supportive group setting, which helps them develop new coping mechanisms and rebuild their social connections. AA succeeds in large part through filling the “God-sized hole in man’s heart.”

What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.

Blaise Pascal, Pensées VII(425)

Pascal was certainly not thinking of heroin addiction when he wrote this, but there is nothing preventing our thinking of it when we read it. He went on to say something that those in recovery may understand: we are “born into a duplicitous world that shapes us into duplicitous subjects and so we find it easy to reject God continually and deceive ourselves about our own sinfulness.“

In my own experience treating narcotic addicts (for nearly a decade; using Suboxone as a 4-month “down ramp” towards sobriety), I found that those who had the best chances of succeeding (at that moment) were those who followed a pathway towards doing better in the “Five F’s” (Faith, Funds (i.e. work), Family, Friends, and only lastly Fun).

Recovery from addiction is not a linear journey, and it’s characterized by its trials, setbacks, and ultimately, resilience. This is exemplified in the story of one patient: a corrections officer (gone bad, shuttling drugs into the prison for a narcotic “commission”) who failed the program and himself, lashing out in frustration, (loudly) calling me an ‘a**hole.’ Lo and behold—months later after exploring options that catered to his immediate desires, he returned. With reflection came a realization that tough love is what makes the difference: “I think I need an a**hole like you to help me get ‘clean,’ for real.” That time was a success, with the difference: his attitude, motivation, and intent.

Appendix I: Contrasting the “Disease” and “Adaptive” Models of Addiction

This appendix presents Bruce K. Alexander‘s 1990 work from The Journal of Drug Issues, exploring the Adaptive Model of addiction. His study, The Empirical and Theoretical Bases for an Adaptive Model of Addiction, proposes that addiction often serves as an adaptive strategy to cope with life’s challenges, diverging from the strictly biomedical perspectives that have come to dominate the field.

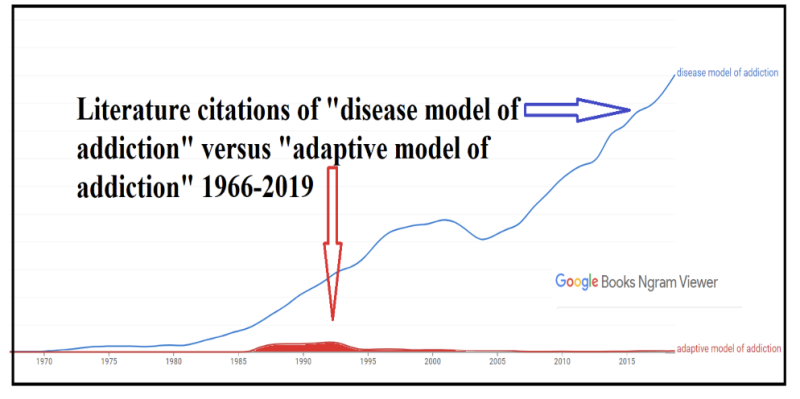

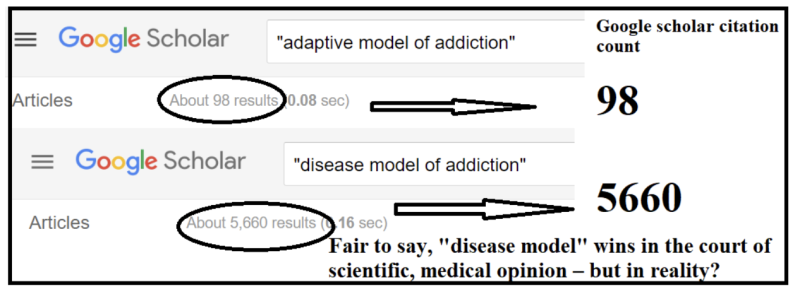

This N-gram viewer graph reveals which theory has “won” this debate. Since around 1990, the Disease Model has gained overwhelming prevalence over the Adaptive Model. This shift underscores a broader move towards viewing addiction through a biomedical lens, significantly shaping treatment approaches and public policy.

Here are the five key differences:

- Nature of Addiction:

- Disease Model: Addiction is viewed as a disease that requires expert treatment. Individuals with addiction are seen as having contracted a disease that drives their addictive behaviors.

- Adaptive Model: Addiction is not considered a disease or any kind of pathology. Instead, it portrays addicts as (theoretically) otherwise-healthy individuals who have been unable fully to integrate into society and thus turn to the most adaptive substitute they can find.

- Direction of Cause and Effect:

- Disease Model: Addiction is seen as the cause of a host of other problems.

- Adaptive Model: Addiction is initially seen as a result of pre-existing problems. Although an addictive lifestyle may create new issues or exacerbate existing ones, these are not enough to outweigh its perceived adaptive benefits to the individual.

- Control Over Addiction:

- Disease Model: Individuals are portrayed as being under the control of the substance or as being “out of control.”

- Adaptive Model: Depicts addicted individuals as actively controlling their own fate, making choices that are self-directed and purposive, even if these choices are not always conscious.

- Role of Exposure:

- Disease Model: Exposure to a drug or activity is seen as a major causal factor in the development of addiction.

- Adaptive Model: The major cause of addiction is attributed to a failure in the integration between the individual and society. Exposure to drugs is simply a way to introduce someone to a possible substitute adaptation; without the underlying integration issues, mere exposure would not lead to addiction.

- Biological Foundations:

- Disease Model: Draws on the medical tradition of biology, focusing on the pathological aspects of addiction.

- Adaptive Model: Based on evolutionary biology, emphasizing adaptation and the interaction between an individual’s traits and their environment.

All well and good, but as with Covid, the “winners” may be somewhat predetermined. The “experts” have weighed in:

Appendix II: A Serendipitous Discovery of Bruce K. Alexander’s Work and the Influential Rat Park Experiment

In the course of writing this article, I have only just now encountered the theories of psychologist Bruce K. Alexander, a figure unfamiliar to me despite a decade spent working in addiction and detox. I had heard about the “Rat Park” experiment (as so probably have you). Rats housed in enriched, social environments (the “Rat Park”) consumed far less morphine compared to those in isolating conditions, suggesting that addiction is more a response to social and environmental factors than merely chemical hooks.

Alexander’s views are articulated through three pivotal points derived from his extensive research:

- Drug addiction is only a small corner of the addiction problem. Most serious addictions do not involve either drugs or alcohol. “Defining ‘Addiction'”, 1988

- Addiction is more a social problem than an individual problem. When socially integrated societies are fragmented by internal or external forces, addiction of all sorts increases dramatically, becoming almost universal in extremely fragmented societies. The Globalization of Addiction 2009

- Addiction arises in fragmented societies because people use it as a way of adapting to extreme social dislocation. As a form of adaptation, addiction is neither a disease that can be cured nor a moral error that can be corrected by punishment and education. “A Change of Venue for Addiction: From Medicine to Social Science” 2013

Efforts to curb addiction (via the disease model) haven’t been effective; frankly it’s been the most counterproductive failure possible. Many professionals fail to help most addicted souls, and the “advanced science” of MMT and replacement narcotic treatments have succeeded only in improving their own positions. The real solution lies in valuing the pathway, maturity, and growth needed in each individual.

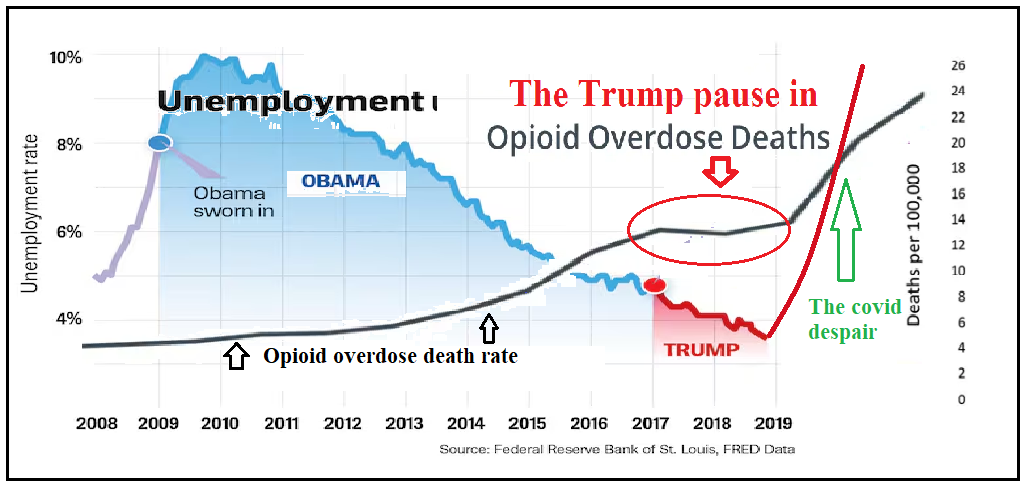

During the Trump era, from 2017 until the Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, the United States saw the first decrease in opioid overdose deaths in decades, a fact largely ignored by the media. While the rise of fentanyl was frequently reported, the overall decline in deaths went nearly completely unmentioned. Here, I will give the New York Times credit.

This drop in opioid-related fatalities may not be attributable, per se, to any direct drug-efforts by President Trump—but rather to his economic magic wand generating historically low unemployment rates. Under Trump, unemployment fell to below 4%, significantly lower than the average ~7-8% during the Obama years. This economic improvement particularly benefited the marginalized sectors of the population, who are often most vulnerable to opioid addiction and despair. With more individuals employed, the cycle of opioid sales, usage, and overdose showed signs of weakening.

This result is very much in keeping with Prof. Alexander’s Adaptive Model. My final wish would be that the Disease Model would adapt to it.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.