“Satchel Paige is supposed to have said, ‘It’s not what you don’t know that hurts you, it’s what you know that just ain’t so.’ ” ~ Warren G. Bennis, On Becoming a Leader

“Managers do things right. Leaders do the right thing.” ~ Warren G. Bennis

On March 25, 2024, the online Medpage Today published an article written by the Presidents of the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics. In it, they make the claim that:

Online misinformation about vaccines harm (sic) patients, undermines trust in science, and places additional burdens on our healthcare system through reduced vaccine uptake. All in all, it is a barrier to protecting public health.

This above article was in turn analyzed in Trial Site News on March 27, 2024, which states:

At the confluence of power and big money comes a tendency for corruption, and without a free and open press, which includes independent physicians making their opinions known, we could easily slip into a dark non-democratic reality.

Arguments were recently heard by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case, Murthy v. Missouri, concerning the ability of the government to partner with social media to restrict free speech regarding matters deemed to involve Public Health. We are awaiting the decision.

The assertions by these leaders of two influential medical organizations raise some interesting questions:

- What exactly is “misinformation” and its somewhat more arcane siblings, “disinformation” and “malinformation?”

- Who decides what information is either “mis,” “dis,” or “mal,” and on what basis is that decision made?

- What qualifications are necessary to become a medical leader? How do they acquire their standing?

In her 2007 article in the Journal of Information Science, “The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy,” Jennifer Rowley discusses the relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom first popularized by R. L. Ackoff in his 1988 Presidential Address to the International Society for General Systems Research.

This is often depicted as a pyramid, starting with Data on the base, progressing to Information, then to Knowledge, and on to Wisdom at the apex. In this model, data consists of alphanumeric representations of signals which are then contextualized into information to make it understandable for further evaluation. Note that at this point, information (“data in formation”) is neutral. As long as it is based on truth (and more on this later) there is no value judgment associated with it. That information is then subjected to further evaluation to produce knowledge. The evaluation of the application of that knowledge produces wisdom.

Note that in this framework, there is only “information,” not “misinformation” (the spreading of false information that may not be known to be false), “disinformation” (the spreading of false information that is known by the spreader to be false), or “malinformation” (the spreading of information that may be true but removed from proper context for a malicious purpose).

All of this is not an intrinsic property of the information itself, but is introduced by another human’s judgment. For something to be deemed “misinformation,” someone other than the communicator of that information has to proclaim it to be “misinformation!” The determination is made by someone, in whose OPINION, the information is deemed to be untrustworthy.

That hinges on the meaning of “truth.” Unfortunately, in the Postmodern world, “truth” is a very malleable quality. There can be “your” truth and “my” truth rather than “the” truth. “The” truth doesn’t exist. And truth, in Postmodernism, is based on ideology. That explains how “Baghdad Bob” could report Iraq was winning the war while US tanks can be seen rolling in the background and how CNN reported the Kenosha, WI riots as “mostly peaceful” with burning cars clearly seen in the background.

In addition, the proclamation that the shared information in question is in fact “disinformation” or “malinformation” hinges on the accuser also knowing the intent of the individual publishing that information. How is that possible?

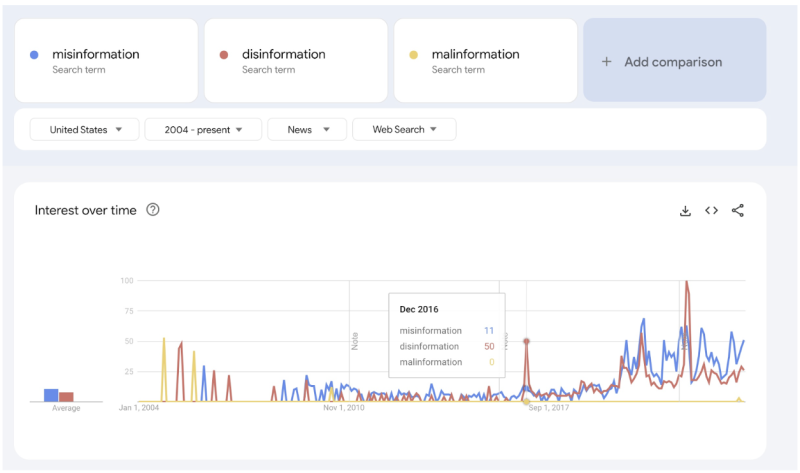

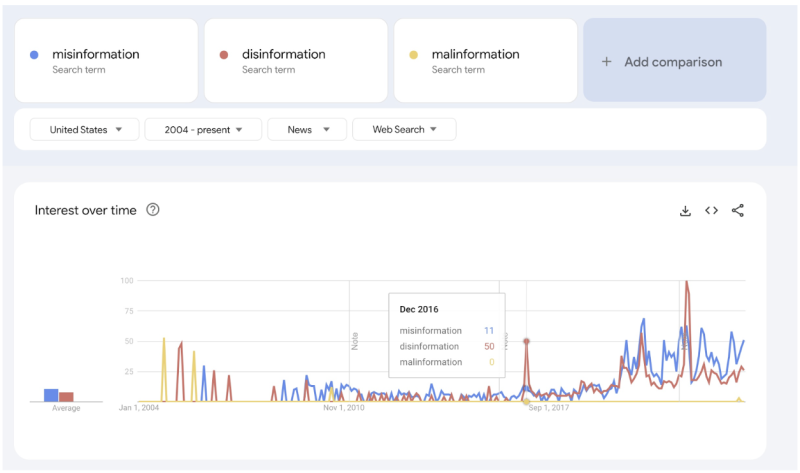

The history of “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “malinformation” is interesting. This time line from Google trends graphically documents the genesis the spikes in the use of these terms:

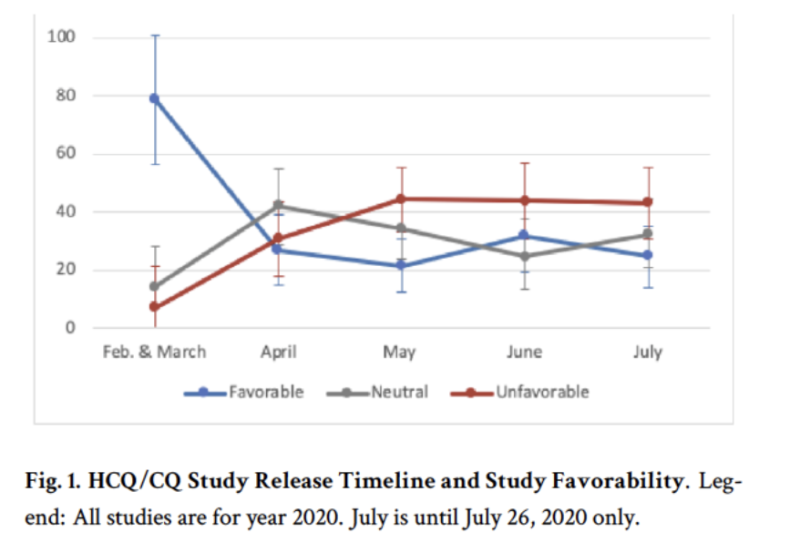

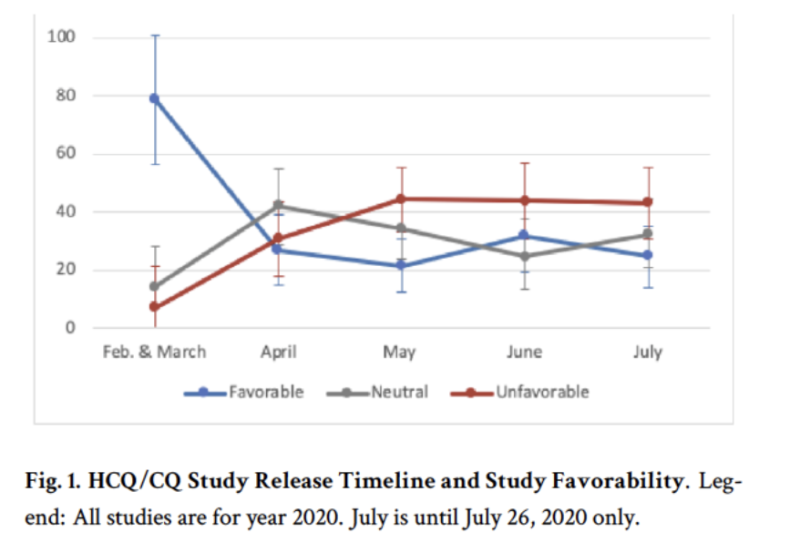

Before Covid, virtually all the mentions of “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “malinformation” were done in the context of political races. The explosion of these words began in March and April 2020, coinciding with President Trump favorably mentioning Hydroxychloroquine as a possible treatment for Covid (taken from):

The primarily political nature of these terms is inescapable. The veracity of political ads is certainly in question. Politicians lie. They lie so much that it has become, if not acceptable, a common expectation: One might say that dishonesty in politics is a long-standing tradition. It could perhaps be understandable to expect that anyone using the terms “misinformation,” “disinformation,” or “malinformation” is doing so for primarily political motives. Unless and until we return to a situation where truth is objective, these terms just may be pejorative euphemisms for what is really just a “difference of opinion.”

Such differences in opinion have always been present in medicine and science. Ideas which ultimately were accepted have first been resisted, ridiculed, or rejected. Without using the word (which had not yet been coined), they were thought by medical leaders of the time to be “misinformation.” These ideas included: antiseptic handwashing, newborn incubators, balloon angioplasty, viruses causing cancer, bacterial cause of peptic ulcers, infectious proteins, germ theory, Mendelian genetics, cancer immunotherapy, and traumatic brain injuries in sports. Imagine if differences of opinion were not just resisted but criminalized! “Planck’s Principle” states that “Science progresses one funeral at a time,” as it is very difficult to challenge the opinion supported by prevailing authority.

What about the statements of medical leaders? Should they carry any more weight than those of an ordinary medical professional? One may hope so, but is that really a valid assumption, especially in our Postmodern world where ideology seems to touch every aspect of our daily lives?

How do medical leaders attain their status? I have no personal knowledge of the two medical leaders who urged the government to police “misinformation.” They may be very fine and honorable people who arrived at their leadership positions because of their clear virtue. I can testify, however, to my own personal experience with medical leadership positions.

In my career I have held leadership positions in local, regional, and national medical organizations. I have been on the Executive Committee of multiple hospitals, President of local medical societies, Chair of a hospital Ophthalmology department, and multiple committees and elected Chief of Staff of a 750-bed tertiary care hospital. I have served on the Board of Directors of my County Medical Society and been a delegate to my State Medical Society. I was a state Councilor of the American College of Surgeons and served on the Academic Senate of a Medical School. Additionally, I served as Secretary of Education of a national medical society and was appointed as a Technical Advisor to the National Quality Forum.

I say all this not to boast…Although I believe I am capable, there was in reality little exceptional about my knowledge and ability. Most of those positions were the result of my willingness to serve and my inability to say no…The majority of these positions were appointed by the then current leadership, and even the few elected positions were the result of being selected as a candidate by a nominating committee composed of the current leadership. In one of the organizations, we had (and still have) “Soviet-Style” elections in which there was only one candidate!

I became disillusioned with the role and impact of medical organizations as I observed that some, but not all, of those who rose to leadership positions were the sort of physician to whom I would not send my own family. They liked the medical politics. They seemed to like it more than the practice of medicine. There can be a very subtle but seductive aspect of leadership positions. It can be easy to like the lifestyle and forget about the purpose.

I remember the conversation I had with my Dad in 1968 when I was trying to decide between a career in medicine and international law. I remember quite clearly telling him after my first job as an orderly in a hospital, Dad, I decided on medicine. You know, there are no politics in medicine…

Well, I was wrong, Dad…

I come back to the two quotes from Warren Bennis at the beginning of this essay. Bennis is known as the “Father of Leadership Development.” If I had my way, his work would be required reading for anyone contemplating a career in healthcare. As physicians, we all should be “leaders of patients” instead of “treaters of disease.”

So, who do I consider medical leaders whose opinion I value? During the past 4 there have been those who conspicuously and courageously stood up when most just shrank into the background because they feared (justly) the repercussions. I am referencing the people mentioned by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. in the Dedication to The Real Anthony Fauci. They are a few out of the hundreds of thousands of physicians, nurses, other healthcare professionals, first responders, and members of the military who stood for informed consent for patients and against forced mandates, but still too numerous to individually name here.

I am also commending the brave physicians (Tracy Beth Høeg, Ram Duriseti, Aaron Kheriaty, Peter Mazolewski, and Azadeh Khatibi) who were responsible for the repeal of California Bill AB 2098 resulting in the affirmation of the rights of physicians (and their patients!) to real informed consent. Also of note are the equally courageous physicians Mary Bowden, Paul Marik, and Robert Apter whose lawsuit forced the FDA to remove its assertions stating Ivermectin was primarily a ”horse dewormer” and had no place in the treatment of human disease.

How ironic that in both these cases, it was the government—the body suggested by the medical leaders to be best qualified to police against “misinformation” in healthcare—which actually fostered “misinformation.”

The physicians who prevailed in these cases proved that they indeed are Leaders of Patients, and not mere Treaters of Disease. They stood up for patients at tremendous personal cost. Like other leaders two and a half centuries ago, they “pledged their (professional) lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor” to a noble cause they believed in. They embody the most honorable traditions of our profession.

THEY are the type of physicians to whom I would send my family…

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.