In a landmark decision in federal court, after a hung jury in the first hearing, the second jury found in favor of fired BART workers who had sued their employer after termination for filing vaccine mandate religious exemption applications. Each of the six plaintiffs in the case was awarded more than $1 million by the jury.

During the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic, governments and employers both private and public across the country instituted vaccine mandates requiring employees to have completed “full vaccination,” typically two doses of the mRNA vaccines, by set dates in fall 2021. Similar vaccine mandates were ordered for military personnel as well as college and university students.

In general, these mandates allowed that mandated individuals could file exemptions based on sincere religious objections or medical necessity, and if these exemptions were granted, employers were then required to seek, in good faith, accommodation positions where the exempted personnel could still work but would pose less of an infection risk to other employees, patients, customers, students etc. This process of exemption and accommodation was covered by Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) rules.

According to the EEOC rules, as interpreted after the Groff v. DeJoy Supreme Court case which was decided in June 2023, employers have been required to establish that employees not satisfying vaccination mandates would create “undue hardship” in order for the employer to terminate the employee. The EEOC rules specify that infection risk, such as that occurring during the Covid-19 pandemic, constitutes a valid hardship risk, but what is in question is whether such risks constitute “undue” hardship as stated in Groff v. DeJoy.

In a sound and rational analysis, the EEOC rules (section L.3) attempt to quantify the degree of infection hardship risk:

“An employer will need to assess undue hardship by considering the particular facts of each situation and will need to demonstrate how much cost or disruption the employee’s proposed accommodation would involve. An employer cannot rely on speculative or hypothetical hardship when faced with an employee’s religious objection but, rather, should rely on objective information. Certain common and relevant considerations during the COVID-19 pandemic include, for example, whether the employee requesting a religious accommodation to a COVID-19 vaccination requirement works outdoors or indoors, works in a solitary or group work setting, or has close contact with other employees or members of the public (especially medically vulnerable individuals). Another relevant consideration is the number of employees who are seeking a similar accommodation, i.e., the cumulative cost or burden on the employer.”

These rules provide a framework for evaluating the degree of infection transmission risk posed by employees, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, in a workplace. What is remarkable here is that EEOC used the “does,” not the “can,” criterion. “Does” is rationality; “can” is fear.

In legal cases at deposition or testimony, science and medical experts are frequently asked questions such as “Doctor, can drug X cause bad event Y?” Medical and science experts live in a mental universe of science theories, and of course, there might be some possible circumstance where drug X could cause bad outcome Y. We were taught in medical school, “Never say never.”

The question however is not really asking whether, in theory, drug X could cause bad outcome Y, but rather whether here on planet Earth, such outcomes actually do happen. The opposing attorney is trying to get a sound bite from the expert that the drug is potentially harmful. So while the question as posed asks “could” (or “can”) the drug do damage, the correct answer from the expert is, “In theory, the drug could do this, but in real-life applications, the drug does not do this.” “Does” conveys a quantitative estimate of how often things actually happen, whereas “can” is a theoretical question with major fear potential.

In 2021, it was not just the general public that had been propagandized to excessive fear of Covid-19, but companies and governments were also made to be afraid. Thus, many company decisions were based on fear, on supposed “worst-case scenarios,” that disregarded the range of effects of the decisions in favor of supposed benefits for reduced risks of Covid infection transmission.

Compounding this problem, the vaccines did appear to reduce risks of Covid transmission during the first half of 2021, giving employers empirical evidence to support their thinking about vaccine mandates.

However, by the time the vaccine mandates were implemented in the fall of 2021, the widespread Delta strain of Covid-19 infection had largely escaped vaccine immunity (remember the first booster campaign?) and thus the evidence of Covid-19 transmission risk reduction for “full vaccination” required by the mandates was virtually gone—except that medical experts for the defendants in the BART and other cases were still using the earlier stale evidence to support their scientific assertions. This also violates EEOC rules which require the use of the latest scientific evidence.

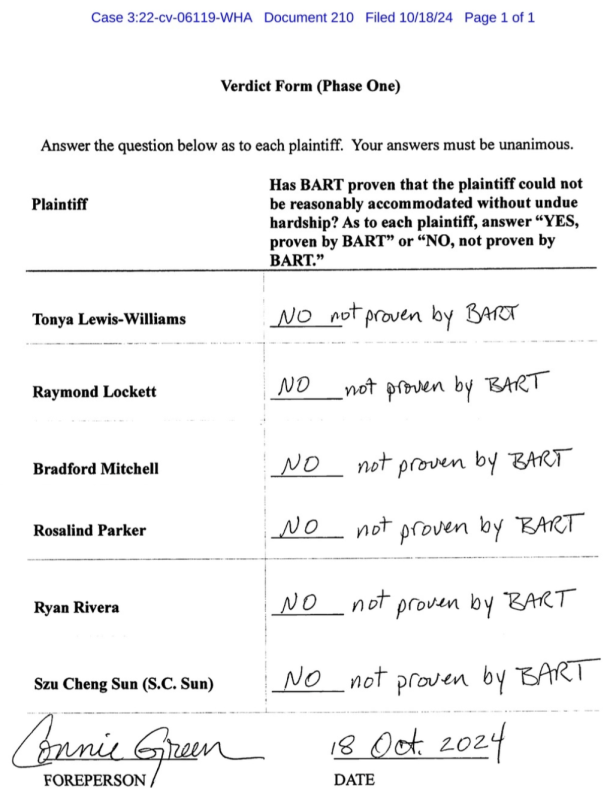

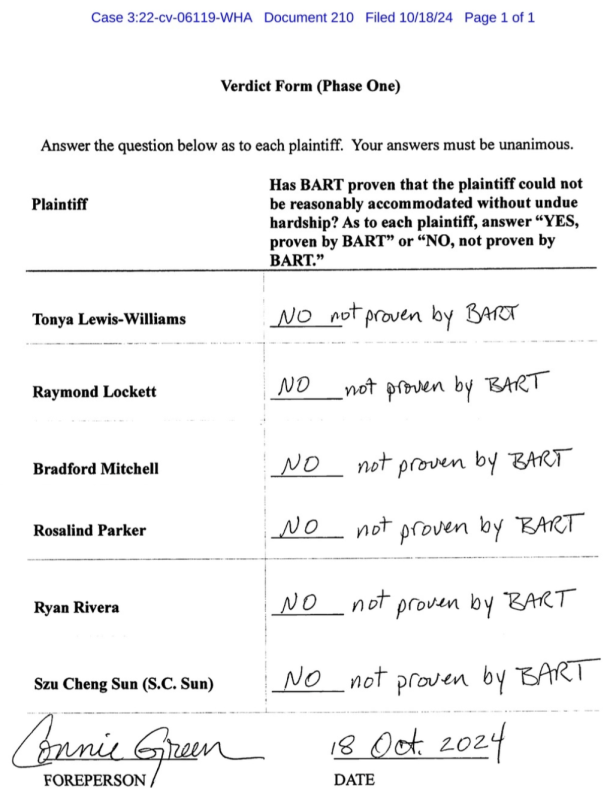

Thus in retrospect, as I had discussed in my testimony as an epidemiology expert for plaintiffs in the BART case, the jury appears to have eventually appraised the circumstances accurately: the small numbers of religiously exempt employees did not pose a major infection transmission risk in comparison to the large BART workforce or to the even larger BART ridership—patrons who themselves were not required to be vaccinated in order to ride the BART trains. In the case’s initial verdict form, the jury unanimously concluded, for each of the six plaintiffs, in response to the question, “Has BART proven that the plaintiff could not be reasonably accommodated without undue hardship?” they wrote, “NO, not proven by BART.”

That is, the fact that such individuals “could” pose infection transmission risks, did not establish an undue hazard that they “would” pose inordinate infection transmission risks. According to the rules laid out by the EEOC, rationality prevailed over fear in this case. One hopes that this legal precedent informs the many similar cases pending, of employees, students, and service members irrationally and unjustly terminated because of fear, not evidence.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.