[This essay by Dr. Joseph Fraiman is one chapter from the recently published book Canary in a Covid World: How Propaganda and Censorship Changed Our (My) World.

The book is a collection of 34 essays from contemporary thought leaders from all walks of life; community leaders, doctors, lawyers, judges, politicians, academics, writers, researchers, journalists, vaccine-injured and data experts. It lays bare how clearly censorship has prevented unfettered access to information, denying us all the ability to make fully informed decisions. As the grip of censorship continues to tighten across social media and the push of propaganda proliferates in mainstream media, this is a book to share with those who have questions, but can’t find answers.]

At first, I hesitated to contribute a chapter to this book due to the fear of being associated with some of the other authors. It wasn’t personal dislike of the other writers, but given that so many of us have had our reputations destroyed these past years, I feared further damage to my own.

It dawned on me that my hesitation was itself a form of self-censorship, and I saw the irony in refusing to write a chapter in a book on censorship. So instead I decided to offer my exploration of self-censorship during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Self-censorship is a common aspect of our daily lives, as it is a basic skill we begin to learn in childhood. Toddlers learn that curse words are fun to say, then quickly learn to censor themselves to avoid punishment. As children, most of us read “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” a fable teaching us that too much self-censorship can become dysfunctional. I believe this fable provides a timeless lesson that fits our current moment.

Self-censorship during the COVID pandemic has taken many forms. As a medical professional and scientist, one might assume that I’m immune to such pitfalls, but the opposite is true. Facing fear of professional repercussions, I have downplayed and withheld discussing valid scientific concerns publicly. Other medical professionals have done the same, thus stifling productive debate, preventing critical variables from being evaluated, and creating the illusion of scientific consensus where one may have never existed.

The media, taking its cue from the experts, disseminated information that fit a specific narrative, ignoring or ridiculing everything questioning it. Journalists who attempted to challenge the narrative came up against the resistance of their superiors and, more often than not, decided to play it safe.

To compound this any expert or publication that dared raise a challenge would be investigated by fact-checkers and predictably labeled as misinformation and subsequently censored. Everyday citizens, on the receiving end of this distorted information machine, were left without any previously respected outlet for any well-founded skepticism. A few spoke out and were virtually ostracized from mainstream society. Many others saw the writing on the wall and, wishing to maintain their relationships and avoid uncomfortable situations, kept their opinions to themselves.

In this way, medical professionals, mainstream media, and everyday citizens, combined with the power of fact-checkers to label misinformation, created a feedback loop resulting in an overly self-censored society. In the remainder of this chapter, I’ll explain these aspects of self-censorship in greater detail through my own experience as a physician and scientist.

While today I am an outspoken critic of COVID-19 orthodoxy, I have not always been so. Early in the pandemic, I trusted “the experts.” I publicly advocated support for their policies and sometimes an even more aggressive approach. As an Emergency Room Physician, I witnessed first-hand a massive amount of death and devastation caused by COVID-19. The ER doc in me was thinking only about saving lives – anything to stop the death around me. I became publicly outspoken on the topic, doing interviews with journalists, writing op-eds and publishing in medical journals.

I believed more aggressive measures would save lives. It’s interesting to note that every time I offered an opinion criticizing federal policy recommendations as not aggressive enough, I found medical journals and news media more than willing to publish my views, even in cases where the evidence supporting my positions was questionable at best.

Despite publicly calling for more aggressive measures without quality supporting evidence, fact-checkers never censored me, labeled my views as misinformation, nor publicly smeared me. During this time I was easily able to publish in medical journals and in the news media. Many journalists began contacting me for my opinions, and I became friendly with several of them. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to hold back or hesitate before sharing my ideas and opinions. However, those advocating for less restrictive measures were fact-checked, labeled misinformation spreaders, censored, and publicly smeared as COVID-deniers, anti-maskers, and anti-vaxxers.

Soon, however, it was my turn. I remember the first time I felt the impulse to censor myself on COVID-19 policy. A friend of mine, a teacher, asked me to speak against school reopening at a Louisiana public hearing in the summer of 2020. Initially I had supported school closures, but by this time I was worried that the data demonstrated that school closures were likely more harmful than beneficial for children and society-at-large. But I didn’t speak my views at the hearing, or anywhere. I self-censored. I was worried that I did not have enough data to back up my opinions on this topic, even though previously I had felt comfortable advocating for more aggressive policies with considerably less evidence.

A few months later, I undertook a study to investigate the mysterious global pattern of COVID-19. Some countries appeared to be suffering far less than others. With two other scientists, we hypothesized that demographics and geography likely explained these unusual patterns. To test our hypothesis, we performed a worldwide analysis. The results of our study explained 82 percent of the national differences in COVID-19 burden, with the major finding suggesting that island nations with aggressive border closures were successfully able to reduce their COVID-19 infection rates. Our results implied restrictive policies could reduce the burden of COVID-19 in island nations. However, for non-island countries, population age and obesity rate were the major determining factors. We realized that if these demographics explained the majority of differences in COVID-19 burden among non-island nations, this strongly suggested policy decisions didn’t have much influence on the rate of spread in these countries.

At this point, I was forced to conclude that I was likely wrong to have advocated for more aggressive policies for the US, a non-island nation in the months prior. However, had I truly been operating according to my scientific principles and without concern for public perception, I would have spoken out publicly regarding the implications of my own research. Instead, I self-censored.

I told myself I needed more data to support such a radical position. Why did I feel comfortable advocating for more aggressive policies on flimsy evidence, but uncomfortable advocating against these policies with more solid evidence? I did not realize it at the time, but I was experiencing a clear double standard on the evidence; somehow mine wasn’t quite good enough, while the limited evidence supporting more aggressive measures rolled out across the nation by the “experts” was more than adequate.

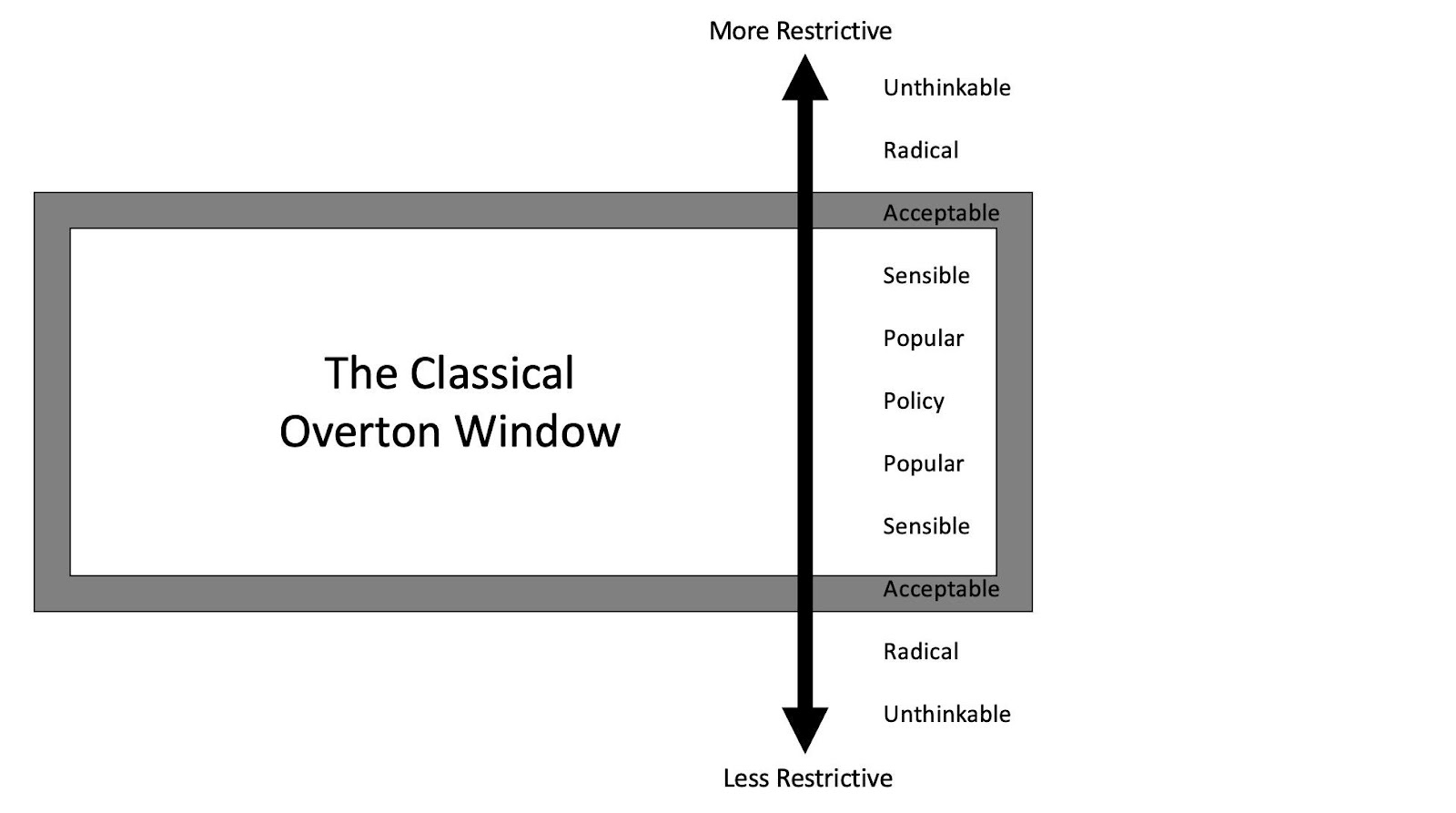

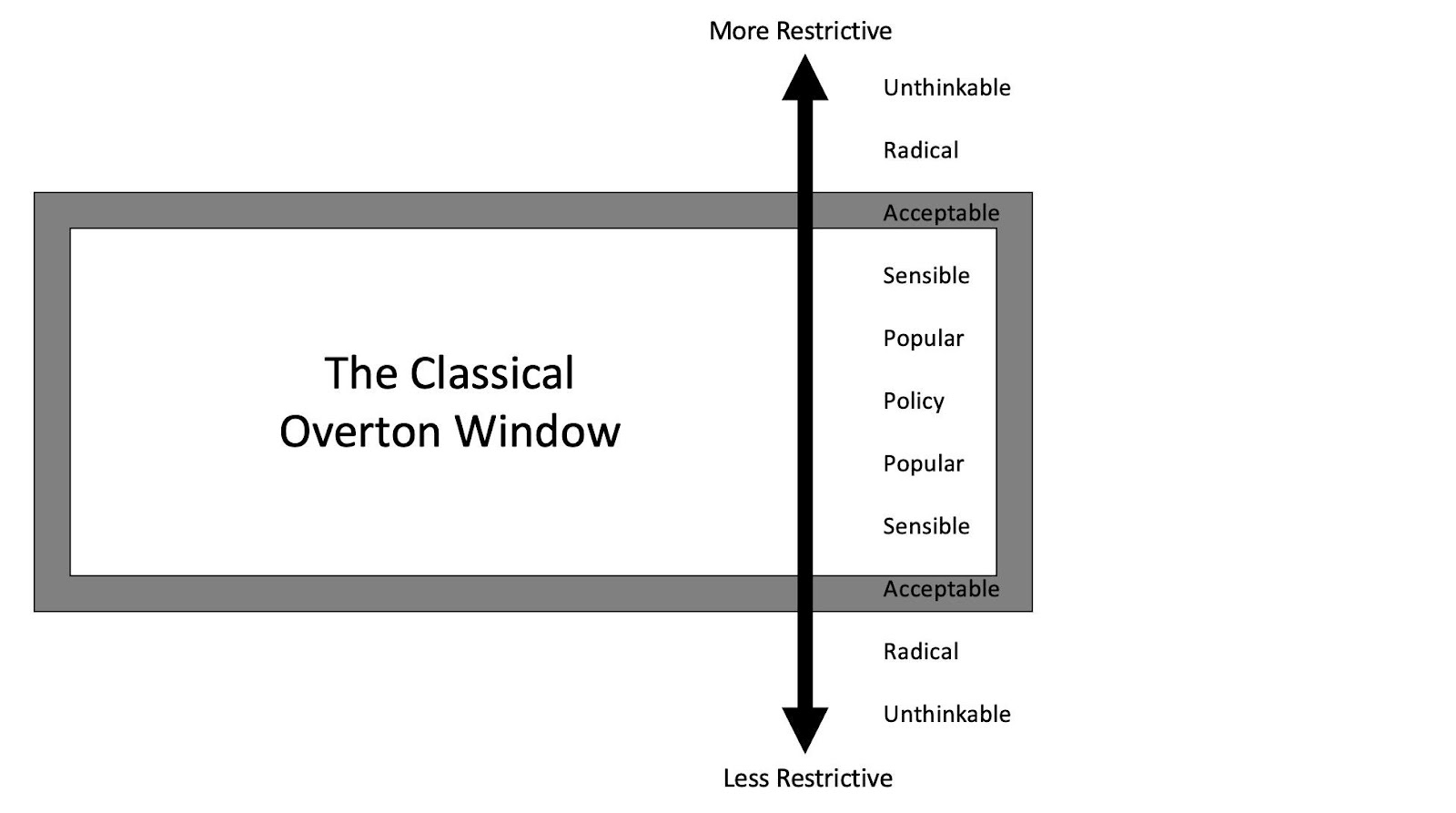

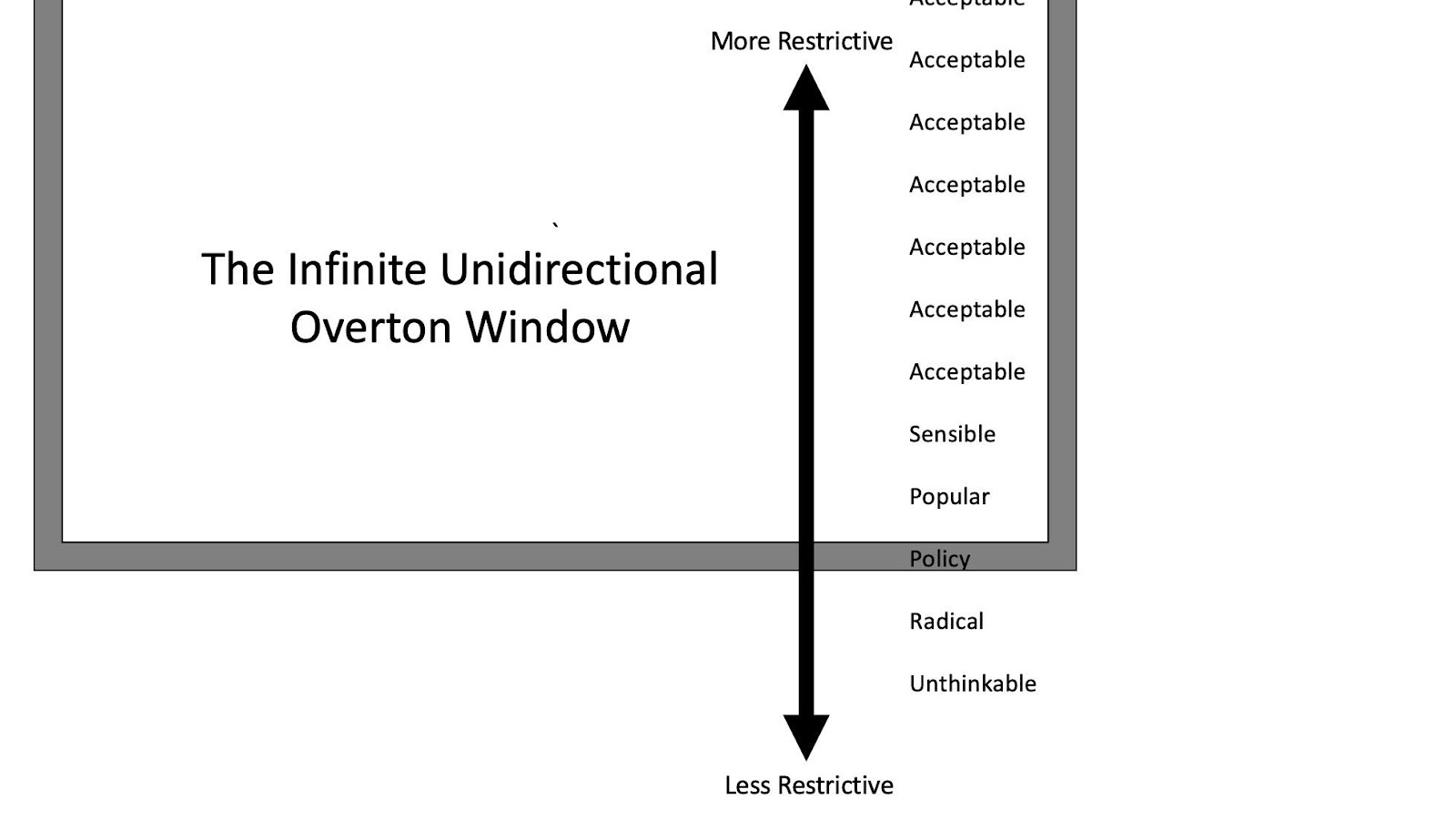

There is a political science term called the Overton window, which gives us a way to understand that there is a range of viewpoints believed to be “acceptable” to mainstream society. Current policy is considered to be at the center of this window. Views on both sides of this window are “popular,” while views a little farther from the center and existing policy are “sensible” and those still farther, “acceptable.” However, views just outside the Overton window are termed “radical;” and views even farther are termed “unthinkable.” In most contexts, people who hold views outside the window censor themselves in public to avoid backlash.

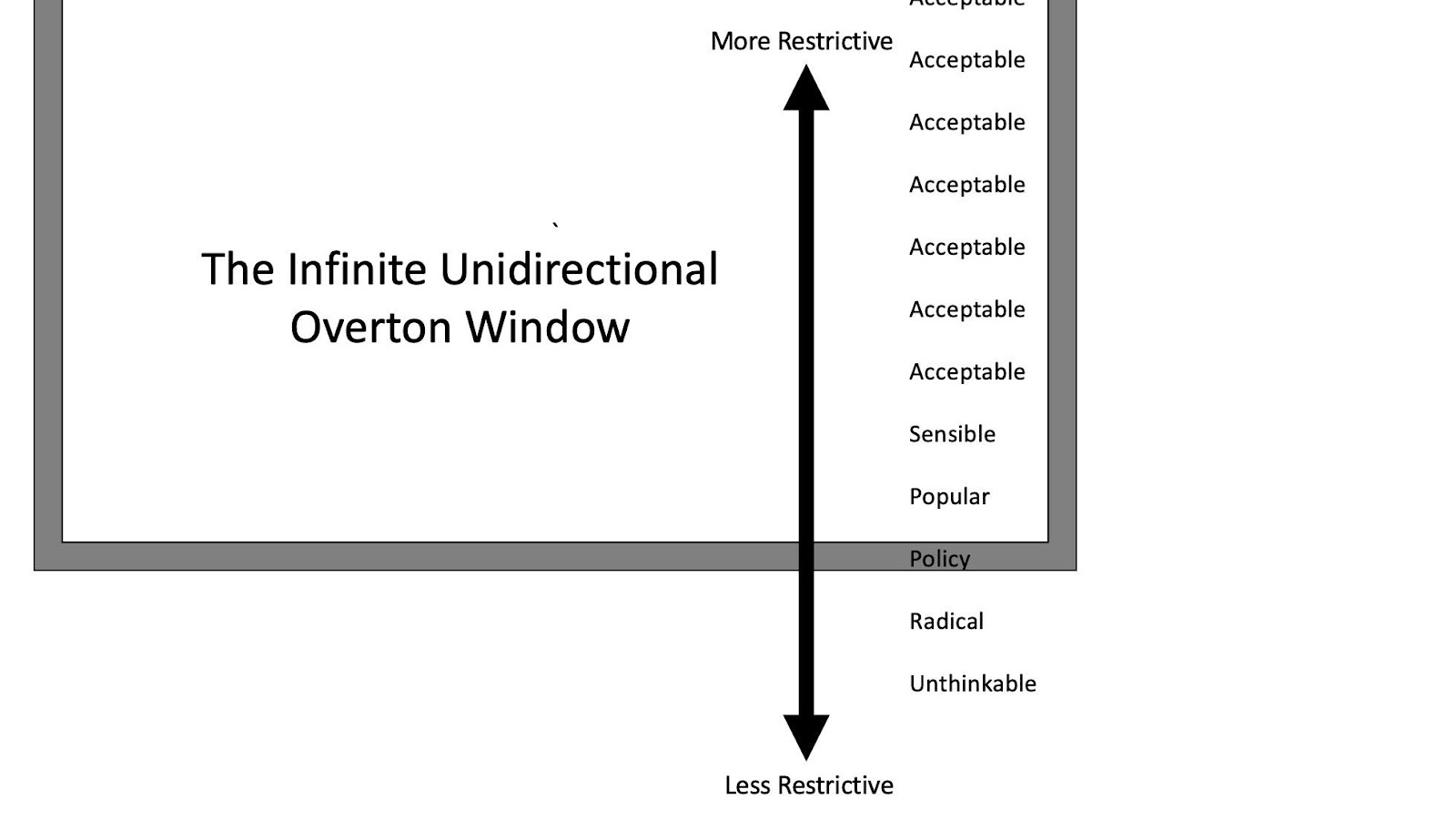

Looking back on the evolution of my opinions regarding COVID-19 policy, the Overton window provides a useful model that shows how social pressures came to bear on many of my viewpoints. Furthermore, the COVID pandemic was a unique sociopolitical event in that it distorted the shape of the Overton window itself. While the normal window of acceptable attitudes and policies occurs in both directions with the ‘radical’ and ‘unacceptable’ extremes at both sides, the Overton window during the pandemic was unidirectional, in that any policy or attitude that was less restrictive than current policy was immediately deemed ‘radical’ or ‘unthinkable’ and would often garner epithets like “COVID-denier” or “grandma-killer.”

Meanwhile, it was infinite, in that on the other side, policies and attitudes remained in the window of acceptability no matter how restrictive the policy or attitude was. In other words, as long as it was seen as a tool to reduce transmission of the virus, it remained in the Window. Thus, when the COVID-19 vaccine was developed and initially sold as the ultimate tool to stop transmission, it fit squarely into this unidirectional Overton window, while anyone raising questions or concerns regarding its efficacy or potential harm fell outside the Window.

Here’s an example that will make this idea more concrete. When the Pfizer vaccine was authorized by the FDA in December 2020, I read the FDA briefing in full and put together a summary for a physician-run site called TheNNT.com. In my review of the Pfizer FDA briefing, I noticed a strangely worded portion in which they discussed, “suspected but unconfirmed,” COVID-19 cases, of which there were thousands, raising serious questions on the efficacy of the vaccine.

Initially, I was reluctant to speak out, as I was concerned that raising the issue prematurely could unnecessarily cause vaccine hesitancy. I felt that I needed to confirm if this was a problem worth discussing. Expressing this concern with various scientists, we understood the potential seriousness of the issue and I was put in touch with Biden’s COVID vaccine Chief Officer David Kessler through email. Kessler assured me this was not an issue, but would not offer the data. I was not reassured. After being denied this data directly from the President’s Chief Officer, I decided I had done my due diligence and was ready to pursue this inquiry on its scientific merits.

My concern was that overestimating efficacy could result in more reckless COVID behavior, subsequently increasing transmission. However, I was unable to get anything published on the topic in medical journals or news op-eds. This surprised me for two reasons: First, up to that point, any report that raised concerns of increased transmission of the virus would have received immediate media attention; and second, other prominent scientists had already felt the issue was important enough to bring it to the attention of the country’s highest authority on the topic.

Despite these setbacks, I continued writing papers highlighting the lack of evidence that the vaccines reduced transmission, and raising concerns about the longevity of protection that they offered. I continued to get rejected from publication after publication. Next, I contacted the same journalists who had been calling me earlier in the pandemic and a predictable pattern emerged. At first they would show immediate interest, but soon after, their enthusiasm would evaporate. I began to lose hope that I would successfully publish on any of these topics in a medical journal or newspaper.

This was my first run-in with the “publishing firewall,” which is what I call the barrier that prevents the dissemination of ideas that fall outside the distorted unidirectional Overton window. It seems that the Window had shifted so that it had become unacceptable to even raise questions regarding the safety and efficacy of COVID vaccines, presumably because the COVID vaccines were touted to reduce transmission of the virus.

Around this time, I didn’t see any articles in any major medical journal or major newspapers that raised these concerns. One exception worth noting was Dr. Peter Doshi. He was able to publish articles on these controversial topics in the British Medical Journal, a top medical journal where he also served as an editor. However, it was his role as editor at BMJ that allowed him to bypass the firewall; thus, he was an exception that proved the rule.

But given that I was not an editor at a medical journal, the media firewall crushed my spirit and drove me to an entirely different form of self-censorship. I no longer censored myself due to fear of repercussions or a false sense of not having enough evidence, but simply to stop wasting time.

My experience as a doctor has taught me that novel medications often fail to deliver on their optimistic promises and it is not until later that we learn they are more harmful or less beneficial than initially believed. That said, other than this general concern regarding all novel medications, when the vaccines were first authorized, I didn’t harbor any specific safety concerns.

My concerns for COVID-19 vaccine safety became much more specific in April 2021, when it was discovered that the spike protein was a toxic component of COVID-19, which explained why the virus caused such diverse harmful effects such as heart attacks, blood clots, diarrhea, strokes, and bleeding disorders. This discovery prompted me to design a study that reanalyzed the original trials and took a magnifying glass to the data regarding reported serious harm. Lo and behold, the preliminary results suggested that in the original trials there was evidence that the vaccines were causing serious harm at a level higher than previously recognized. Given my past experiences, I was not optimistic at this point that I’d be able to publish, so I tried to hand off the study to Peter Doshi, the very editor at the BMJ who had shown success publishing on these controversial topics previously. In the end, he convinced me to stay on and work with him.

We put together a team of seven internationally renowned scientists. Along with myself and Doshi were Juan Erviti, Mark Jones, Sander Greenland, Patrick Whelan, and Robert M Kaplan. Our findings were highly concerning. We soon found that the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in the original trial could be causing serious harm at a rate of 1 in 800.

Prior to publication, we sent the paper to the FDA to alert them of our concerning findings. Several top FDA officials met with us to discuss the study, indicating that they recognized its significance. Despite that interest from the policy-makers, we still came up against the publishing firewall as our paper was rejected by journal after journal. It was only after much persistence that we were able to publish the paper in the peer-reviewed journal, Vaccine.

Now with a carefully performed study published in a preeminent journal, I learned about some of the other drivers that encourage experts to censor themselves: public smearing, misinformation labels, and reputation destruction. As I will show, these forces were being driven in part by a dysfunctional system of media fact-checking that ironically suppressed scientific debate in favor of accepted narratives.

It’s easy to forget that before 2020, fact-checking played a very different role in our media and journalism. Traditionally, a fact-check article might appear as a corollary to the original article for readers who doubted or wanted to verify its credibility. This meant that the reader would read the original article and then, if they were curious, read the fact check, coming to their own opinion on the balance of two or more sources. According to a 2016 national survey, less than one-third of Americans trusted fact-checkers, so it wasn’t even a given that a critical fact-checking piece would spell doom for the original article. Furthermore, fact-checks rarely, if ever, weighed in definitively on controversial medical science claims.

This model had already started to change with the dominance of social media, but the pandemic, and with it the ‘infodemic,’ accelerated this transformation. In response to growing concerns of misinformation on social media, fact-checkers and social media companies stepped up their efforts to control it. They began displaying misinformation labels on article links and outright preventing people from seeing and/or spreading articles deemed ‘misinformation.’ With this newly granted power, fact-checkers became our society’s arbiters of scientific truth, tasked with separating fact from fiction.

Science is not a collection of facts. It is a process that allows us to better understand the world around us. This might come as a surprise to those of us who were taught scientific ‘truths’ in the classroom that we had to memorize for tests, but in reality, medical science is premised on uncertainty. Generations of medical school students have been told: “Half of what we taught you is wrong; the only problem is we don’t know which half.” The point is that no one, not even the world’s top medical scientists, can determine absolute truth. Yet, fact-checkers were tasked with just this, and in their effort to do so they confused confident expert opinion for facts, when expert opinions are not facts. Indeed, even a consensus of medical experts is not a fact.

For these reasons, fact-checking is a flawed system even in the most ideal circumstances. Once political context and unavoidable bias are taken into consideration though, the situation becomes even more concerning. At the outset of the pandemic, the pattern that emerged was that only certain types of statements and articles were getting fact-checked. Specifically, articles that contradicted or challenged official policy tended to face relentless scrutiny from fact-checkers, while the original government statements themselves somehow evaded fact-checking altogether. For example, in March 2021, CDC director Rochelle Walensky stated that vaccinated people, “don’t carry the virus,” and “don’t get sick.” Fact-checkers did not write articles investigating the validity of Walensky’s statement. Yet, months later when this quote was mocked on social media videos and posts, fact-checkers saw it as necessary to publish articles describing these social media posts (which were mocking a false statement from a federal official) as misleading. The fact-checkers argued that Walensky’s statement was taken out of context and reminded us that CDC data showed that the vaccine reduced hospitalizations and death. However, neither of these defenses spoke to the effect of the vaccine on transmission rates and so neither one refuted the fact that Walensky’s original statement was false and should have been subjected to at least the same level of scrutiny as social media posts made months later. Nonetheless, the social media posts mocking Walensky’s statement were subsequently either censored or subjected to a ‘false information’ warning label while her original statement never received such treatment.

Interestingly, the only examples I have found where people challenged government policies and statements and did not garner aggressive fact-checks were those that advocated more restrictive policies. In this way, fact-checking decisions mirrored the distorted unidirectional Overton window that I had come across previously.

As one would expect, these dynamics have helped to create the illusion of ‘scientific consensus’ which is actually just a case of circular logic. Here’s how it works. A federal agency makes a statement, which is then criticized or challenged by a scientist, journalist, or viral social media post. Fact-checkers then ask the federal agency about the veracity of their original statement. The agency predictably claims that their statement is accurate and those challenging it are incorrect. The fact-checker then goes to the experts to verify the agency’s claim. The experts, who by now instinctively understand which answers are safe and which ones risk reputational harm, confirm the agency’s claim. The result is that fact-checking agencies consistently label articles and statements outside the unidirectional Overton window as ‘misinformation.’ In this manner, government ‘expert opinions’ morph into ‘facts’ and dissenting opinions are stifled.

This is how our paper, with its carefully worded conclusion that “these results raise concerns that mRNA vaccines are associated with more harm than initially estimated at the time of emergency authorization,” written by a team of internationally renowned scientists, peer-reviewed by experts in the field, and published in a preeminent journal of vaccinology, got slapped with a ‘misinformation’ label and censored on social media.

At this point, it’s important to consider how the unidirectional Overton window, the publishing firewall, and the fact-checking feedback loop all work together to create an ecosystem that engulfs medical professionals, media figures, and everyday citizens.

For healthcare professionals and scientists, a ‘misinformation’ label given by a fact-checker can serve as a scarlet letter, destroying reputations and threatening careers. As a response to these negative incentives, healthcare experts with critical views of existing policy often do the most natural and reasonable thing: they censor themselves. The result of this is that the exact experts on whom we rely to provide us with unbiased, science-based information are themselves compromised.

Now consider the journalist who gets their COVID information from the experts. Even if we presume that they are operating according to the most thorough methodologies and reporting with an open mind and the best intentions, they are most likely only going to be able to find experts promulgating opinions within the distorted Overton window. In addition to eliminating valid scientific ideas that fall outside the Window, this has the effect of manufacturing a consensus even if one doesn’t exist. Furthermore, even for the intrepid journalist who is able to find an expert opinion outside the Window, they will most likely find that their boss is unwilling to publish something that will probably get labeled as misinformation and hurt their organization’s bottom line.

Finally, consider the effect on the everyday citizen who is listening to these experts and consuming the products of these media companies. Given all the filters that have distorted the information to this point, it’s no wonder that the range of acceptable opinions on the pandemic is so narrow that it creates the illusion of a scientific consensus. Furthermore, we now have a clearer picture of why everyday citizens might feel the need to self-censor, even if they have a well-founded, thoroughly examined, scientifically-based opinion. After all, if the “expert consensus” that is being communicated by the media is able to say confidently, for example, that the COVID vaccines prevent transmission of the virus, that means that any conflicting opinion on the matter must be ‘misinformation.’

All of us self-censor every day. Sometimes we withhold statements that might hurt the feelings of a loved one; other times we refrain from offering an unpopular opinion when around friends; often we express our views in a way we think others will find more palatable. All of this is understandable and, to a certain extent, unavoidable. When a global pandemic upended the way of life for virtually every person on the planet, these patterns were bound to play out on a larger scale. That, too, to a certain extent, is understandable. However, hundreds of years ago our ancestors devised an ingenious method to help us reduce uncertainty in a highly complex world. This method differed from prior belief systems in that, instead of deferring to authorities who claimed a monopoly on absolute knowledge, it acknowledged, and even celebrated uncertainty.

The method was not a blanket defense for something we want to be true, nor a reframed version of what we previously believed. This was science, an evolving method of questioning and still the most effective tool we’ve devised to gain information about the world around us. When experts fail to live up to their scientific duties because they are stuck in their own self-perpetuating cycles of self-censorship, it is detrimental to the cause of science. I am one of those experts who failed to live up to my scientific duties and I value science above all else, yet still I failed to live up to my own standards of truth-seeking.

Consider what that means on a mass scale when even the most staunch proponents of science can be made hesitant in the face of societal pressures. Now consider what kind of society we want to live in and ask yourself: what duty does each of us have to make that a reality?

I propose it is time we all yell out loud “The Emperor has no clothes!”

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.