In the first quarter of 2020, the first Covid-19 pandemic wave swept the world. This caused a wave of fear to also sweep across the world, leading to governments taking desperate countermeasures that imposed limits on everyday freedoms never before seen in our lifetimes. Stories about Covid-19 went viral in the media, which have covered the pandemic 24/7 throughout 2020 and 2021 to the exclusion of many important health-related topics.

The world succumbed to a kind of Covid monomania.

What were the origins of this extraordinary response, why was it so extreme, and how well have governments justified the harsh countermeasures to the public? There are several key themes and concepts underlying the narratives that governments and media have used to justify the response which have lodged in the public mind.

An influential underlying driver has been the subjective feeling that extreme measures are proportionate to an extreme threat.

There was an early theme in the government and media narratives that compared this pandemic to the 1918 influenza pandemic, in which over 50 million people lost their lives worldwide. The total number of deaths for Covid-19 in the US has passed the number of deaths in 1918 – however, the US population is now more than three times larger than 1918. And the years of life lost are proportionately smaller again as Covid-19 mortality increases exponentially by age, whereas the 1918 pandemic took people at earlier ages when they had many more years of life to expect. Here is one media report that explains this well.

So, the Covid-19 pandemic, while of course it deserves to be taken seriously, is more comparable to the lesser-known Asian flu of 1957-58, which is estimated to have caused over one million deaths worldwide (when the world population was less than a third what it is now). In some countries (for example, Australia) all-cause mortality actually went down in 2020, and whole regions such as Oceania did much better than the worst affected regions, Europe and the Americas.”

In any case, even if the Covid-19 pandemic was comparable in scale to 1918, it simply would not follow that extreme measures would be more effective than moderate measures.

The origins of the great wave of fear lie in the first quarter of 2020, when the Imperial College London Covid-19 Response Group published their notorious Report 9, which predicted that 2.2 million people would die in 3-4 months of 2020 in the US if aggressive government interventions were not put in place.

This was based on unspecified “plausible and largely conservative (i.e. pessimistic) assumptions,” which were not supported by any evidence or references.

The key concepts were, first, that dire outcomes would ensue if normal social interactions in the population were maintained during a pandemic caused by a ‘novel’ virus they had never encountered before. There were historical precedents for this when colonial invaders made first contact with indigenous populations, but nothing like it in modern developed country populations. Second, the ICL group concluded that interactions needed to be reduced by 75% over eighteen months until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more), by reducing mobility through “general social distancing.”

The report generated three scenarios based on these key assumptions: 1) “do nothing”; 2) a package of measures designed to “mitigate” the effects of the pandemic; and 3) a package aimed at “suppressing” it.

As the assumptions were not in any way supported by evidence, the projections of extreme loss of life in the ‘do nothing’ scenario represent an unfalsifiable hypothesis. No governments went down that path and they all implemented countermeasures to a greater or lesser extent. To justify these measures, they have continually held the hypothetical threat of massive loss of life over us.

What is remarkable looking back on it, however, is that the projections presented in the ICL report that started it all do not convincingly favor suppression.

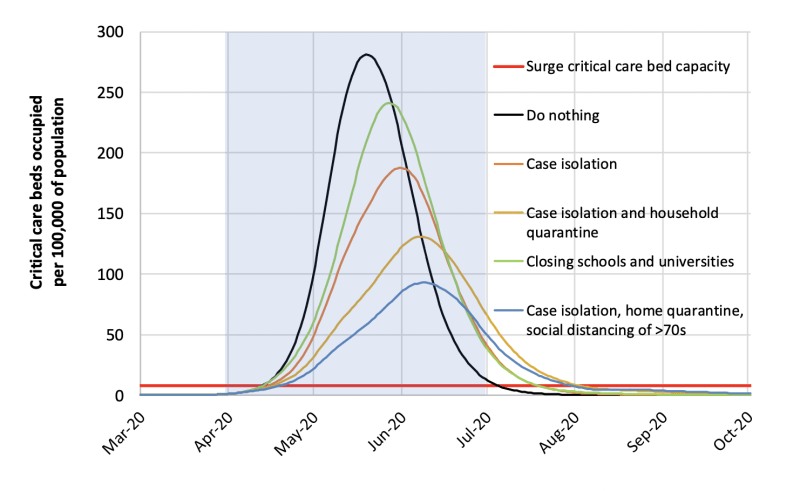

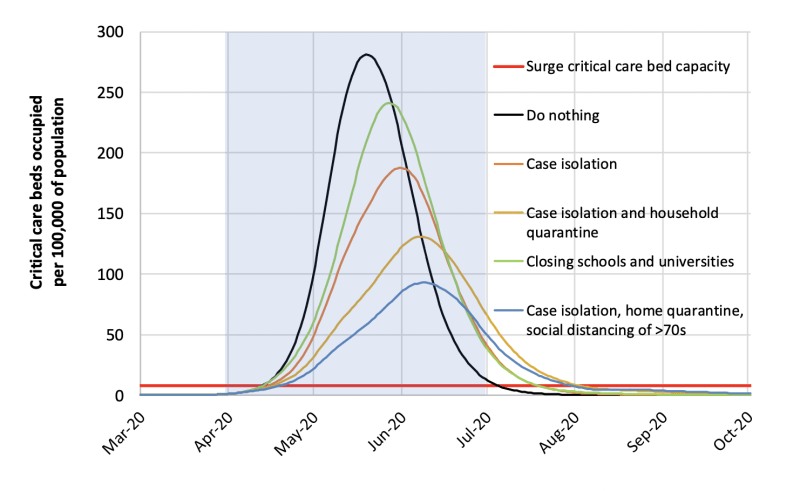

Figure 2 in the report shows epidemic curves for various mitigation scenarios starting with ‘do nothing,’ which supposedly results in a peak of demand for ICU beds towards 300 per 100,000 of population.

The traditional package of case isolation and home quarantining, together with social distancing only for the over 70s results in a peak below 100.

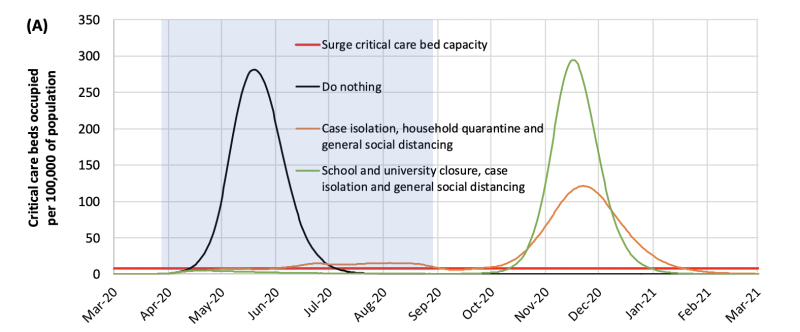

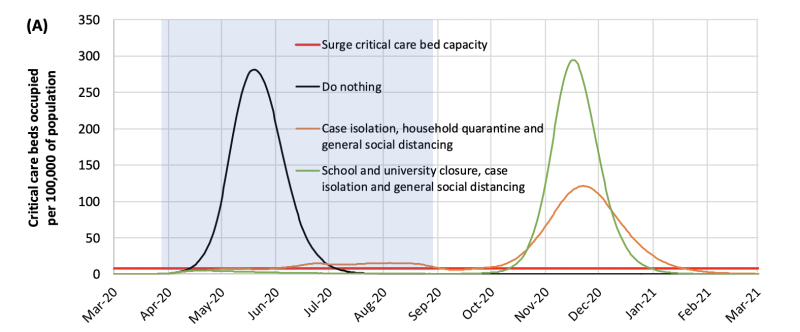

Figure 3A presents curves for suppression strategies including the one with general social distancing which shows a similar curve, but the peak is actually higher, well over 100 ICU beds per 100,000 of population.

The traditional package with the addition of social distancing for the over 70s is clearly the winning strategy in the report, and bizarrely, is quite close to the ‘focused protection’ strategy advocated by the distinguished authors of the Great Barrington Declaration.

So, the (imaginary) data presented in the Ferguson report actually shows a better outcome from mitigation – but they recommended suppression!

This sleight of hand has occurred with some other papers where the authors reach conclusions that are at odds with their own results.

A pandemic of modelling then took place across the world, with many other groups making local projections along the same lines, generating worst case scenarios that cannot be tested.

The models have subsequently been found to be extremely fallible, with highly variable outcomes depending on questionable assumptions and key values selected.

Where they generate factual scenarios that can be tested, they have been caught out. When Italy moved to relax its restrictions in the summer of 2020, the ICL Covid Response Group warned in Report 20 that this would lead to another wave, with peaks higher than before and tens of thousands of deaths within weeks.

As Jefferson and Hehneghan pointed out, “by 30 June that year, just 23 daily deaths had been reported’.” This shows us that the assumptions about the effectiveness of the interventions are particularly weak.

Likewise, a modelling group at my Australian alma mater predicted that with “extreme” social distancing the number of infections in Australia would peak at around 100,000 per day towards the end of June 2020. In fact, the total number of cases peaked at a little over 700 per day in August, many orders of magnitude less than the projection.

Nonetheless, these reports were taken at face value and scared the hell out of the world’s governments and then their peoples, and the governments rushed to accept the group’s recommendation to implement harsh interventions until a vaccine became available.

Another key underlying theme in the narratives has been “we are all at risk.” Government representatives have been at pains to emphasise that anyone can fall victim to Covid, including young people, and therefore everyone needs to join in the common enterprise to defeat it. Media articles often play up uncommon examples of younger people who became seriously ill in hospital, but downplay all reactions from vaccines as “rare.”

But the reality has always been that risk of Covid (the disease) rises exponentially with age. Charts showing rates of hospitalization divide sharply between the upper age quartiles and the lower age quartiles. There are certainly cases of disease in all age groups, but Covid (and Covid mortality) are sharply distinguished from the 1918 flu by being concentrated strongly in the post-working age population.

Despite this, governments have relentlessly pursued universal strategies, targeting (if that’s the word) everyone in the entire world.

In the first instance they went beyond the traditional strategy of testing and tracing to find and quarantine sick people and their contacts, and extended this to quarantining the entire population in their homes for the first time in history, using stay-at-home public health orders to enforce lockdowns. This has never been recommended by the World Health Organization, which has consistently advised that lockdowns should only be used for short periods at the beginning of a pandemic, to buy governments some time to put other strategies in place.

By 2021 it became possible to evaluate the outcomes of these policies against real data.

One study strikes at the heart of the key assumption that reducing mobility improves outcomes. This study was published in the world’s top medical journal, The Lancet, and shows that lockdowns do have an effect on infection rates, but only in the short term.

The authors reviewed the evidence from 314 Latin American cities looking for an association between reduced mobility and infection rates. They concluded that: ‘10% lower weekly mobility was associated with 8·6% (95% CI 7·6–9·6) lower incidence of COVID-19 in the following week. This association gradually weakened as the lag between mobility and COVID-19 incidence increased and was not different from null at a 6-week lag.’

Although they present the findings as supporting the link between mobility and infection, in fact they severely undercut the utility of any link. Lockdowns do reduce infection rates, but only for a few weeks, not for any meaningful period. And this study does not draw any conclusions about the effect on the outcomes that matter, such as hospitalisations and mortality.

Hard evidence that lockdowns improved these outcomes is very difficult to find. In some instances, lockdowns were imposed just before the peak of the epidemic curve, which then turned down. But we must avoid falling into the post hoc fallacy, assuming that because ‘B’ follows ‘A’ in the alphabet, ‘A’ must have caused ‘B’.

Empirical studies of different countries or regions mostly fail to find significant correlations between lockdowns and any change in the course of epidemic curves resulting in improved outcomes (particularly mortality). For example, a study of mortality outcomes in all countries with more than 10 deaths from Covid 19 at the end of August 2020 concluded that:

The national criteria most associated with death rate are life expectancy and its slowdown, public health context (metabolic and non-communicable diseases…burden vs infectious diseases prevalence) economy (growth national product, financial support) and environment (temperature, ultra-violet index). Stringency of the measures settled to fight pandemic, including lockdown, did not appear to be linked with death rate.

Consider, for example, the case of two cities – Melbourne and Buenos Aires. They have been competing for the title of world’s highest number of days in lockdown (in total). Both cities have imposed measures at the same level of stringency, but Buenos Aires has six times the number of total deaths (taking into account its larger population). Clearly the differentiating factors must be environmental. Latin American countries combine high urbanisation levels and lower GDP per capita, so the differences in living conditions and health systems are driving these differences in outcomes, not the feeble attempts by governments to manage the circulation of the virus.

Some studies purport to find that lockdowns help, but this is usually based on extrapolating from short-term reductions in infection rates and/or counterfactual scenarios based on modelling. There are many studies that find that lockdowns fail, which have been gathered together into various compendia on the web such as this one. There are too many unfavourable findings and not enough favourable ones to justify governments relying on this severe and harsh option.

A few countries, mainly islands in the Pacific regions, managed to hold the virus at bay and go beyond suppression to achieve periods of elimination, or “zero Covid.” Politicians vowed that they would not just “bend the curve” but crush it, or drive the virus into the ground,” as if viruses can be intimidated by political pressure the same as people.

Having no land borders makes it a lot easier to control interactions with the outside world, but as Covid-19 became endemic in all other countries, the zero-Covid countries reluctantly relinquished the dream and prepared to open up and learn to live with the virus.

Their governments could still spin this as consistent with the original rationale of a period of eighteen months of suppression “until a vaccine becomes available’.” The ICL group never spelled out what would happen when a vaccine did become available, but there was an unspoken implication that suppression would no longer be needed, or at least some of the suppression measures would no longer be needed.

Vaccination would in some way end the pandemic, although how exactly was never spelled out. Would this effectively be a suppression strategy giving way to a mitigation strategy? Consistent with government approaches throughout the pandemic, no objectives or targets would be set against which success could be measured. But vaccination was certainly supposed to stop the spread.

Governments are vulnerable to action bias, the assumption that in a crisis, taking vigorous action (any action) is better than restraint. They are expected to actively manage crises. As the epidemic waves mount, they come under irresistible pressure to hold them back, to go further, and then further again. Attacking the waves in the present became an overriding imperative, and longer-term collateral damage from the countermeasures has weighed far less in the balance, because it extends beyond the electoral cycle.

The world’s governments are now repeating their original mistaken model of implementing universal, one size-fits-all measures, this time pursuing universal vaccination – “vaccinate the world.” They still want to “drive the virus into the ground” and prevent it from circulating in the community. This is often said to be necessary because it will reduce the likelihood of new variants emerging, which supposedly remains higher so long as there are communities in the world that are not fully vaccinated.

“No-one is safe until we are all safe” is the prevailing slogan, supporting a goal to ‘end the pandemic.’ An alternative perspective is that implementing mass vaccination in the middle of a pandemic would create evolutionary pressure that would make it more likely that troublesome variants would emerge. This view has been widely debunked in the media, but without reference to contrary research.

As we have seen, the main groups at risk are the older quartiles. An alternative strategy would be to focus on vaccinating these groups, and allow the lower risk quartiles to encounter the virus, recover usually after a mild illness and develop natural immunity. This would arguably give greater protection against later infection than vaccination. Gazit et al found that vaccinated individuals were 13 times more likely to become infected compared with those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Natural immunity may also protect against a broader range of variants with vaccination giving very specific protection against the original variant.

A “focused protection”’ model was advocated by one of the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration (with others) in a contribution to the Journal of Medical Ethics.

There should have been a deep strategic debate about these two alternative strategies, but there was not. Governments continued down the one-size-fits-all path without considering any other options.

Equally, weight should be given to raising Vitamin D levels in these most vulnerable groups, many of which don’t get out much and so lack exposure to sunlight. Already before Covid 19 came along, a comprehensive review had established that Vitamin D ‘protected against acute respiratory tract infection overall,’ especially for those most deficient, which is likely to include most residents of elderly care homes.

Since the onset of this pandemic, more specifically, studies have found links between low Vitamin D status and Covid-19 severity. One such study found that ‘regular bolus vitamin D supplementation was associated with less severe COVID-19 and better survival in frail elderly.’ As a contributor to The Lancet summed it up: “Pending results of [more randomised controlled trials] of supplementation, it would seem uncontroversial to enthusiastically promote efforts to achieve reference nutrient intakes of vitamin D, which range from 400 IU/day in the UK to 600–800 IU/day in the USA” (see Vitamin D: A case to answer’).

A meta-analysis of the use of Vitamin D in treatment concluded:

As a number of high-quality randomized control studies have demonstrated a benefit in hospital mortality, vitamin D should be considered a supplemental therapy of strong interest. At the same time, should vitamin D prove to reduce hospitalization rates and symptoms outside of the hospital setting, the cost and benefit to global pandemic mitigation efforts would be substantial. It can be concluded that further multicenter investigation of vitamin D in SARS-CoV-2 positive patients is urgently warranted at this time.

And yet in the first phase of the pandemic, this benign strategy with a prior track record against infectious respiratory diseases was overlooked in favour of a harsh and completely novel strategy with no prior track record and little supporting evidence. The 2019 WHO review of NPIs for influenza did not even cover stay-at-home orders.

The sole reliance on vaccination to save the day at the end of the suppression period is looking increasingly shaky already as we move into the last quarter of 2021. Israel has been the world’s laboratory for testing the effectiveness of universal vaccination using the new mRNA vaccines. But the research on outcomes from Israel and the United Kingdom has revealed that:

- Protection against infection steadily wanes over the months (see pre-print here)

- Protection against transmission is even more short-term, evaporating after three months (see pre-print here).

Consequently, Israel experienced a third wave of the epidemic peaking on 14 September 2021, more than twenty per cent higher than the second wave. Vaccination did not stop the spread.”

So, where to from here? The answer is obvious to the world’s governments – if vaccination is not working well enough yet to end the pandemic, we must double down and have even more vaccination! Bring out the boosters! Governments have bet the farm on vaccination, but it cannot deliver because it only addresses part of the problem.

But the strategies that have been followed since the outset of the pandemic have failed to end the pandemic and have not evidently contained it especially in the worst affected countries in Latin America.

We are constantly told to “follow the science,” but key findings of science that do not fit the dominant narrative are overlooked. We have had 19 months of essentially futile attempts to stem the tide, causing deep, widespread and long-lasting adverse effects to lives and livelihoods, yet there is no hard evidence that going for suppression instead of mitigation has produced better outcomes.

Good governance requires that these issues and strategic choices should go through a deliberative process in which the strategic options are weighed up before a decision is made, but this has never happened, certainly not in the public eye.

At some stage, it may no longer be possible to avoid hard strategic thinking. Only 6% of US Covid cases do not also involve “comorbidities;” in other words concurrent chronic and degenerative conditions such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension. Most of these are the “diseases of civilization” that are strongly correlated with the Western diet and sedentary lifestyle factors.

This caused the editor of The Lancet to write an opinion piece provocatively called “COVID-19 is not a pandemic,” by which he meant it was actually a ‘syndemic,’ in which a respiratory illness is interacting with an array of non-communicable diseases. He concluded: “Approaching COVID-19 as a syndemic will invite a larger vision, one encompassing education, employment, housing, food, and environment.”

Over a year later, his appeal has clearly been too sophisticated and has fallen on deaf ears. Governments prefer the quick fix. There has been no larger vision. Short-term strategies that can be boiled down easily into slogans have prevailed.

The first step towards that larger vision will be to abandon the leading myths that:

- An extreme threat justifies the use of extreme measures

- We are all at risk so the same extreme measures must be used for everyone.

Instead, governments should move towards a more nuanced strategy, with additional measures differentiating by risk group.

And address the underlying causes of the crisis in health amongst our seniors. SARS-CoV-2 is just the trigger that has precipitated the crisis. In order to solve a problem, you first have to understand what the real problem is.

Governments have sought to micromanage the circulation of a virus around the world, by micromanaging the circulation of people. It didn’t work, because they conceptualised the circulation of the virus as the entire problem, and ignored the environment in which it was circulating.

Those who have challenged lockdown strategies have been labelled “science deniers.” But on the contrary, there is a dearth of scientific evidence to support these strategies and a high number of negative findings. The challengers are challenging the basis of conventional opinion, not the science.

The house of science has many rooms. Policy makers need to go beyond cherry-picking the evidence in one or two of these rooms. They should open all the relevant doors and represent the evidence that they find validly. Then have the debate. Then set some clear objectives against which the success of the chosen strategies can be measured.

There should be a clear relationship between the strength of the evidence required for a strategy and the risk of adverse effects. The higher the risk, the higher the bar should be for evidence. Harsh policies should require very high quality evidence.

Governments got it all wrong. They should have chosen the mitigation strategy all along, leaving the management of pathogens to actual medical professionals who deal with individuals and their problems rather than push a central plan hatched by computer scientists, political leaders, and their advisors..

Decision-making processes have been ad hoc and secretive, a model that leads to governments making colossal mistakes. It is very hard to understand how lockdowns have become a standard operating procedure despite there being no evidence that they improve outcomes and vast evidence that they wreck social and market functioning in a way that spreads human suffering.

Good governance requires that we do better next time. The basis of government decisions that affect the lives of millions must be publicly disclosed.

And especially: “follow the science” – all of it!

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.