My good friend professor Yuri Maltsev died this week and I’ve spent these mourning days recalling our conversations. He was a leading economist in the old Soviet Union, as the top advisor to Mikhail Gorbachev’s chief economist. He defected in 1989 before the Soviet Union fell apart. We became fast friends just after he landed in DC, and we spent a year or more together collaborating on many projects.

He was a font of amazing stories about how things really worked in the Soviet Union. Contrary to what US economists were claiming until the very end, it was not a rich country with mighty industrial achievements. It was a poor country where nothing worked. There were no replacement parts for most machines including tractors. He doubted that there would ever be a nuclear exchange simply because most Soviet workers knew that the bombs were all for show. If they ever dared press the button, they would most likely blow themselves up.

As the systems of command and control in those states fell apart (Russia, East Germany, Romania, Poland, Czechia, and so on), Yuri was in a position to advise the reforms. To his sadness and contrary to his advice, even though the parties and leaderships collapsed, there was almost no attempt to reform the health-care sectors of these countries. They left them all in place while focusing on things like heavy industry and technology sectors (and here banditry took over).

Yuri saw this as tragic because, to his mind, the corruption of health care in the Soviet Union was central to the disastrous quality of life that the people experienced there. Though doctors were everywhere and minted daily, people who were sick could hardly get effective treatment at all. Most of the best therapeutics were homegrown. People would only go to the doctor much less the hospital if they had no other options. This is because the instant you entered the system, your personhood was left behind and you became part of the modeling target.

All health care was driven by statistical goals, just as with economic production. Hospitals were under strict orders to minimize death or at least not to go over target. That led to a perverse situation. Hospitals would take in the mildly sick but refuse to admit anyone likely to die. If patients in critical care declined too rapidly, the first priority of the hospital was to get them out before they died so as to reduce the amount of death on the premises.

All of this was done in the hope of gaming the vital statistics to make it look like the centralized and socialized health-care systems worked when they clearly did not.

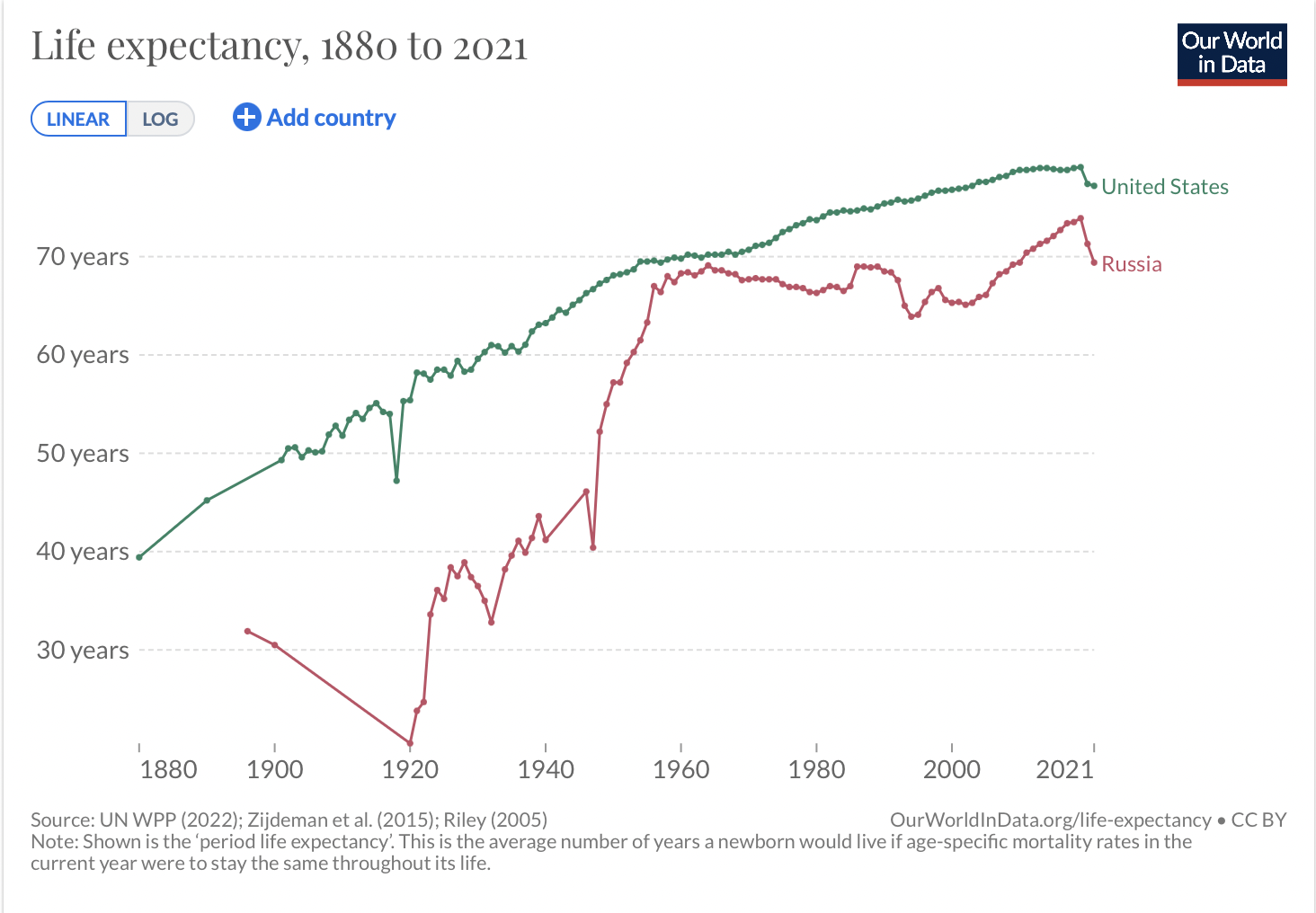

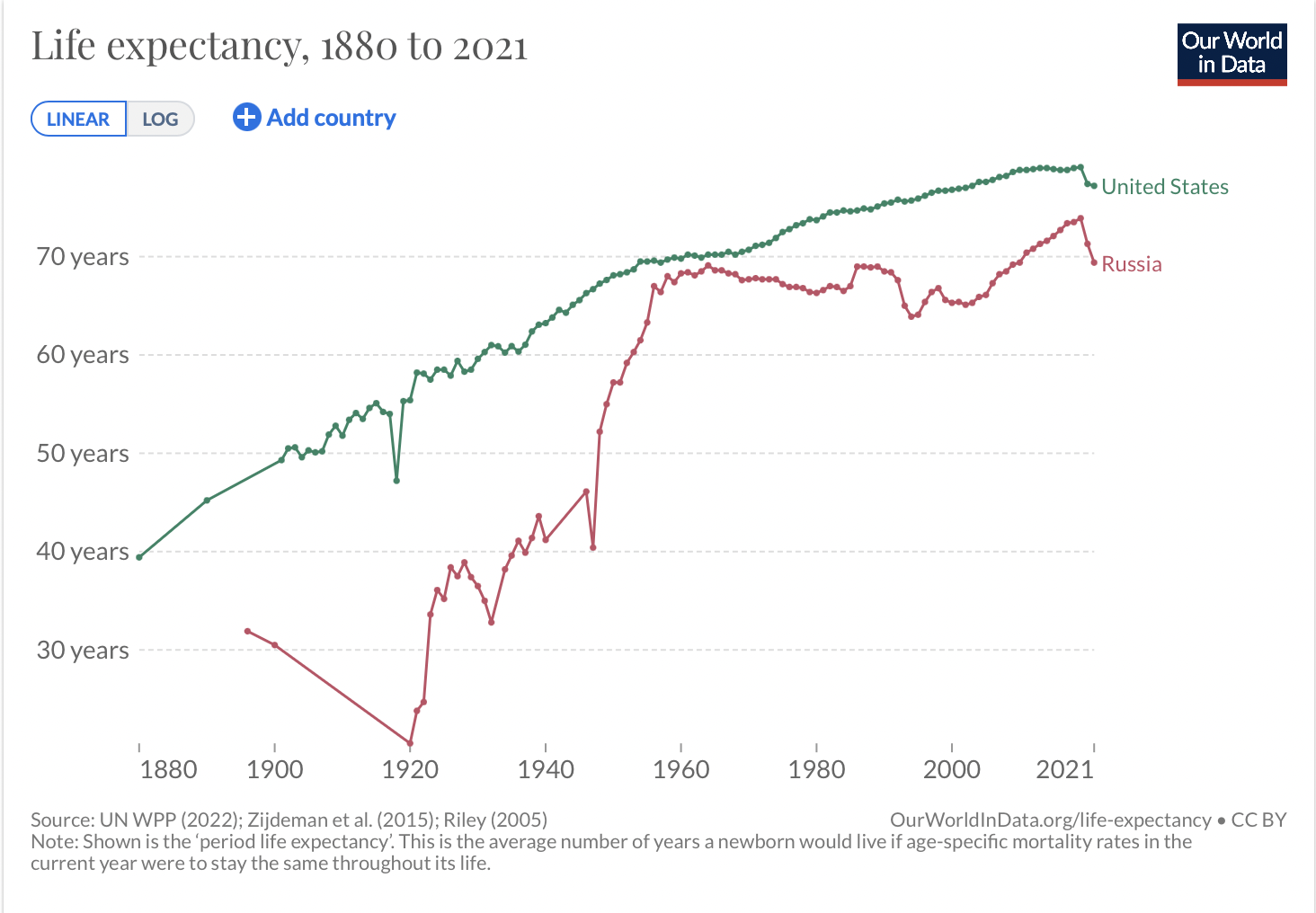

None of this could ultimately hide the vital statistics, which, Yuri explained, truly do tell the story. From 1920 to 1960, life expectancy did increase dramatically though never quite reaching asat high as the US. But after 1960, it began to decline even as it was rising more and more in the US and in non-communist countries around the world. This continued until the regime finally collapsed, at which point life expectancy began to rise again.

Notice too that life expectancy in both countries has begun to fall again, and dramatically, following pandemic lockdowns and mass vaccination, which is a tragedy that cries out for explanation.

Back to Yuri’s point however: the health-care system and its statistical goals served as a major source of brutality and corruption in Russia. When government gets hold of medical systems, they use them for their own propaganda ends and purposes. That’s true whether the real goals are medical or not.

This happened in both countries following lockdowns, and many others as well. Maybe it is only a short blip or maybe it is the beginning of a long trend of decivilization. Either way, the central plan is not working.

In the US, in nearly every state, regardless of whether the virus was spreading rapidly with significant medical consequences, hospitals were forcibly reserved only for emergencies and Covid patients. Elective surgeries were out of the question, as were cancer screenings or other routine checkups. This left most hospitals in the country with very few patients and a gutting of their profitability models, leading to furloughs of thousands of nurses during a pandemic.

It also created a situation in which hospitals were desperate for a revenue source. By government legislation, a subsidy was provided to them for Covid patients and Covid deaths, thus incentivizing medical institutions to classify everyone with a positive PCR test as a Covid case, regardless of what else was wrong with the patient.

This began almost immediately. Here is Deborah Birx speaking to the issue on April 7, 2020.

This practice continued for two years, leading to a massive confusion about how many people actually died of Covid and skewing all existing data on the case fatality rate. Leana Wen of CNN argued in a Washington Post article that now perhaps only 30% percent of the people labeled as a Covid hospitalization really are that. She explained further in a CNN interview.

As Leslie Bienen and Margery Smelkinson note in the Wall Street Journal:

Under the federal public-health emergency, which begins its fourth year on Friday, hospitals get a 20% bonus for treating Medicare patients diagnosed with Covid-19. … Another incentive to overcount comes from the American Rescue Plan of 2021, which authorizes the Federal Emergency Management Agency to pay Covid-19 death benefits for funeral services, cremation, caskets, travel and a host of other expenses. The benefit is worth as much as $9,000 a person or $35,000 a family if multiple members die. By the end of 2022, FEMA had paid nearly $2.9 billion in Covid-19 death expenses.

Further, doctors all over the country are facing massive pressure to list as many deaths as possible as Covid deaths.

These programs create a vicious circle. They establish incentives to overstate the danger of Covid. The overstatement provides a justification to continue the state of emergency, which keeps the perverse incentives going. With effective vaccines and treatments widely available, and an infection fatality rate on par with flu, it’s past time to recognize that Covid is no longer an emergency requiring special policies.

Maltsev was right about this as with so much else. The further we move away from health care as essentially a doctor/patient relationship, with freedom of choice on all sides, and the more we allow central plans to replace on-the-ground clinical wisdom, the less it looks like quality health care and the less it contributes to public health. The Soviets already tried this path. It did not work. Health-care by modeling and data targeting: we tried it over the last three years with horrible results.

As Maltsev would put it, the need to de-Sovietize medical care applies in every country, then and now.

[This is my other tribute to Yuri, which ran at the Epoch Times]

Yuri N. Maltsev, Fighter for Freedom

As often happens, I only wish I had one last chance to say goodbye to economist Yuri N. Maltsev, my good friend who died this week. We could have spent an entire day and evening reflecting on the great times we had together, laughing uproariously the entire time.

It has been a few years since I last saw him, which I believe was at an event in Wisconsin where he taught economics. We agreed on most everything but there was some tension between us in those days because we had a disagreement over Trump: he was more for him than I was.

That didn’t matter so much, however, because our history stretched back to the final days of the Cold War. I was living in Northern Virginia, when I heard that a major economic advisor to Mikhail Gobachev had just defected. This was before the entire Soviet project fell apart. I couldn’t wait to meet up, so through an intermediary we met for lunch. He had been in the United States only a day or two at most.

At the D.C. restaurant where we met, he ordered a sandwich that came with potato chips. He kept cutting them with a knife and eating them with a fork. Even though we were trying to be formal with each other, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I interrupted to explain that in the United States, we tend to pick up potato chips with our fingers. He laughed uproariously and I did too. Thus was the ice broken. After that we hung out nearly daily for longer than a year.

We became very close collaborators on projects. In those days, the whole world was fixated on the meltdown of a succession of states that once rallied around Soviet-style economics. Not too many months after Yuri got here, those regimes fell like dominos. The world was looking for interpretations, and Yuri was the perfect person to give them. He could talk a mile a minute, and I was anxious to transcribe everything he said and get it in print.

So his experience in D.C. was an absolute whirlwind of interviews, articles, speeches, meetings, and so on, including frequent consultations for the CIA for which he was paid handsomely. He used to laugh at how dumb they were to pay him to show up and tell an afternoon of jokes.

For anyone else, this instant fame would be a drug that produces arrogance. But Yuri had been around the block too long in the political world in Moscow and very clearly recognized that the fakery of Moscow and Washington had much in common. So he adopted a light attitude toward it all. He laughed through the whole ordeal from the beginning to the time he left for a teaching position in the Midwest.

Oh, my goodness, the times we had together!

Let’s start with his small apartment. When he moved in, it was empty. Two days later, it was stuffed from one end to the other and every closet was full. I came over and I was startled because what he had in there was rather unconventional. He had bought an extra toilet, the stuffed head of a deer, piles of paintings, piles of kitchen things, several desks and three sofas, plus more. Even an old piano. I was astonished. We could barely get in the door.

I asked why he had done this. He explained that in the Soviet Union, everything not nailed down was immediately stolen, even paper clips at the office. The whole society was based on thieving and hoarding and he had happened by a couple of yard sales and simply could not believe his eyes that all this amazing and great stuff—either unavailable in Russia or unaffordable—was just sitting there for the taking for a few bucks. He simply could not resist. I explained that this stuff would always be available and that he didn’t need to do this. He agreed and decided to have a sale of his own. He tripled his money.

This is just how Yuri was: seemingly reckless but actually oddly brilliant. He started buying cars the same way simply because no normal person could get a car in the Soviet Union without getting on a yearlong waiting list. In the United States, he could buy half a dozen cars in a day, which he did. They lined the streets outside his apartment. Only a few worked, sadly, but that was fine. A few weeks later, he sold all those cars at a profit too. This guy was magic.

He later did the same with real estate of course, and enjoyed his wild time as a slumlord. I used to go on rounds with him as he attempted to fix the plumbing and electricity at the apartments he now owned. He knew nothing about either but did his best and just laughed it off. He would also hang around the city court looking for properties confiscated and resold for nonpayment. He would buy them and resell them.

Yes, he loved his life as a capitalist! And he was darn good at it too.

Social life was good too. We had a big circle of friends, and Yuri would drag me to all sorts of parties and bar hops with them. I wonder how he made so many friends so fast. He explained that most of them were either KGB or CIA spies checking in on him and monitoring his behavior and contacts. So of course they were following me too, along with several honeypots. I was absolutely astonished and alarmed.

He explained that it was nothing to worry about. They are just people with jobs to do, and part of their business was converting their single-agent positions into double-agent positions and then to triple-agent positions, and so on, knowing the whole time that of course their bosses were doing the same. That’s how nuts the world had become by 1989 and 1990. Everyone was spying on everyone and everyone was lying in that world.

He said just to treat it all with humor and enjoy it. So I did. Crazy times. The spies eventually left me alone when they discovered I was not a spook but a book collector.

Yuri was quite fashionable in D.C. in the day, so anyone he asked over to dinner would naturally come immediately. He invited a few of our spy friends plus the ambassador to Czechoslovakia and his wife to dinner at his apartment. I arrived early to help him with dinner but he didn’t want help. He was making “Georgian Chicken.” I asked what that is. He said it was everything in his refrigerator in a big pot of boiling water. He explained that when you are foreign, guests forgive everything.

Just before dinner, he went across the street to get some wine and vodka and returned with a disheveled man. He was homeless. Yuri bumped into him on the street and figured he would make a good guest. True story.

The guests all arrived at this little apartment. He had only card tables on which to eat, having sold all his other furniture. The ambassador’s wife took off her full-length mink and sat down. Yuri passed around empty water glasses for everyone and filled them half-full with vodka. He explained that to honor his Russian heritage everyone would need to drink down the whole glass before dinner.

Everyone complied but of course immediately everyone was drunk. That made the strange evening go better.

Yuri then served a plate of saltine crackers with meat on the side. After some time, I decided to try the meat but the ambassador’s wife got my attention with a silent headshake of: no don’t eat that. I wondered why and then I realized: Yuri had sliced up a package of raw bacon and served it as an appetizer. He did not know because there was no bacon in Russia when he was there.

Eventually the huge pot of boiling stuff landed in the middle of the table and everyone ate, and truly it wasn’t bad at all! Georgian Chicken indeed.

At every possible opportunity, I would have Yuri to my place for all-day hangouts. I would have plenty of sausage and vodka for him and just ask questions about his life and observations. I would sit at the desk and he would pace around madly and tell extravagant stories of his history as a Soviet economist. When I wasn’t doubled over in laughter, I was typing frantically to get his stories on paper. Two days later we would go to print with it all.

What a glorious outlook on life he had. He saw the hilarity of life all around him everywhere. But this was also backed by extraordinary erudition. While studying at Moscow State, he read deeply in the history of bourgeois economics, simply because both he and everyone around him knew for certain that Marxism was a bunch of hooey. He was astonished to find that many academics in the United States took all that claptrap seriously.

Have you ever been around a person whose intelligence and good humor just shows through on their very person, just when walking into a room, and everyone else was so drawn to it and they got on board? This was Yuri Maltsev. Another person I knew with the same gift was Murray Rothbard. So you can imagine what it was like when they met. The whole room became absolutely explosive.

Great times those were. We watched his home country fall apart in real time along with the fall of all states in Eastern Europe and the Berlin Wall. I was wildly optimistic about the future but Yuri was more wary. He had already seen how bureaucratization in the United States was growing and many of the same political pathologies that wrecked Russia were growing in the United States. He did his best to stop them with his writing and speeches and teaching.

He leaves behind a tremendous legacy. The deep sadness I feel in his passing is mitigated by the incredible and delightful memories of our times together. He surely did affect my life in wonderful ways, and so many others. I miss you Yuri! Please have a glass of tall vodka on me and I shall drink to you and your great life as well.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.