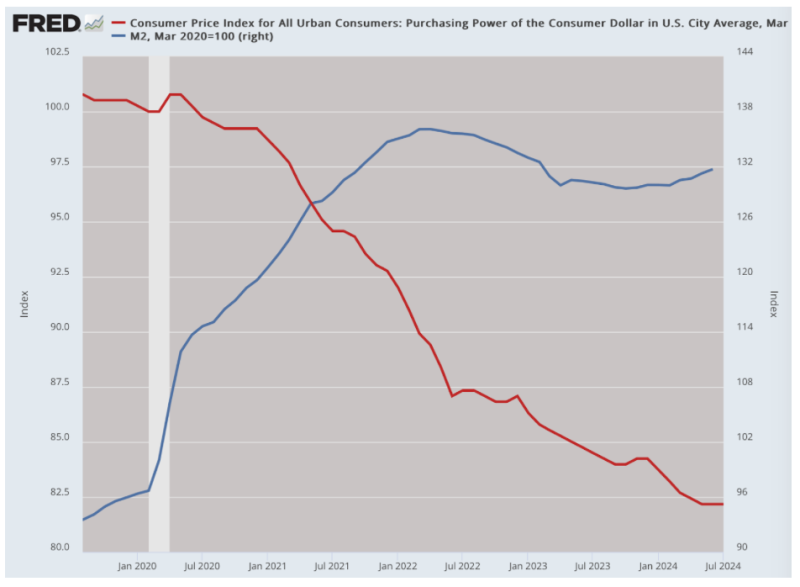

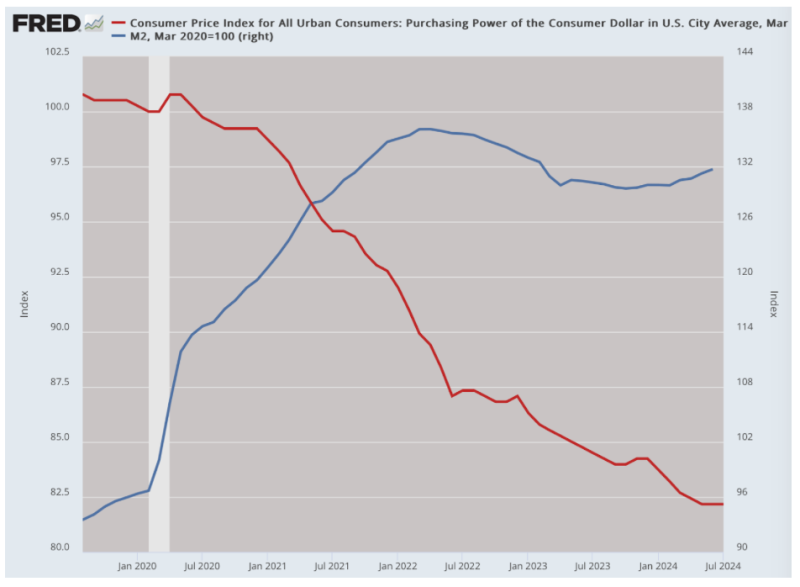

The US’s serious bout of inflation – mirrored in many countries in the world – was set in motion in the first week of March 2020, like much of the rest of our ongoing emergency. This was a fortnight before the lockdowns were announced, indicating that much was going on behind the scenes. The Federal Reserve turned on a dime to provide enormous liquidity to the system, just days following the CDC’s briefing of the national press of coming lockdowns, about which the Trump administration seemed then to know next to nothing.

The fiscal and monetary fun lasted only so long. Following the inauguration of the new president, the first round of bills started coming due, and that has continued until the present, rapidly wiping out the value of the stimulus payments that seemed to have made everyone suddenly rich without working.

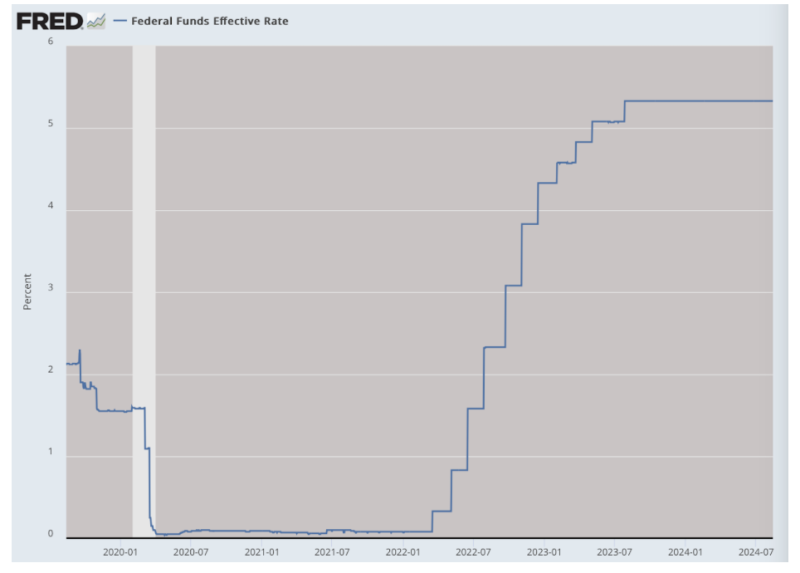

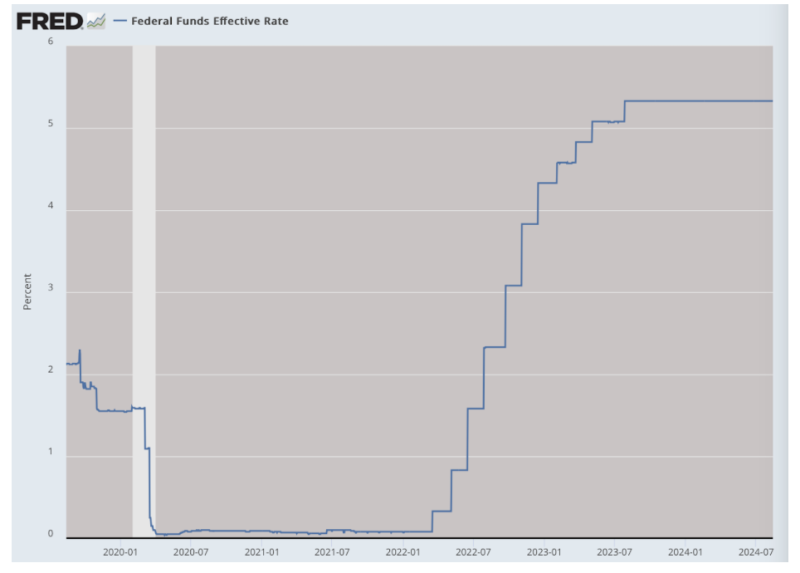

Only after two years and after some 10 months of resulting declines in purchasing power, along with supply chain breakages that left so many goods in shortage, did the Fed start to worry and raise interest rates from zero percent. That was presumably designed to sponge up the excess liquidity that had been injected directly to the veins of economic life. The Fed’s action slowed but did not end what they had unleashed to deal with the virus that was widely advertised as universally deadly even though every specialist knew otherwise.

Normally, higher rates would inspire new savings, especially since it was the first time in nearly a quarter-century that saving money alone was a means of making money faster than money was losing value. That did not happen, simply because household finances were suddenly squeezed and all discretionary income redirected toward paying the bills. Today some 40 percent of people polled say they are barely getting by, while house buying is out of the question.

Here we are four years and six months later, and what do we hear? On the one hand, we are being told that the inflation problem is largely solved even though there is plenty of evidence that this is not correct. We don’t even have a verifiable reading on precisely how much damage has been done to the value of the domestic dollar. They say it is around 20 percent but that figure includes a large range of inaccuracies and excludes many of the categories of purchases that have gone up the most (such as interest rates). As a result, we do not really know the fullness of the problem. Could the dollar have lost 30 or even 50 percent or more of value in four years? We await better data.

All official spokespeople, however, say that the problem is largely gone. And that makes it especially strange that just this week, the candidate who is leading in the polls for president, Kamala Harris, has announced support for nationwide price controls on groceries and on residential rents. If she is willing to do that, she would be willing to expand them to any category of goods or services.

Despite her claim that that is the “first ever” such imposition – why is that a bragging point? – she is wrong about that. On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon imposed a 90-day freeze on all prices, wages, rent, and interest. There were new boards of enforcement set up for both wages and all prices. It was the first 90 days to flatten the curve.

No surprise, the administration had a hard time backing off from this policy and reimposed them again in 1973. They were not finally fully repealed until 1974. Ninety days turned into three years, just as two weeks turned into two years.

What Nixon did in his time was in response to a perceived emergency. The demands on gold seemed to necessitate a dramatic change in monetary policy and a closing of the gold window, while the price controls were designed to shore up Nixon’s standing in the polls. He was forced to choose between what he knew was right and what he thought would bolster his popularity. He chose the latter.

Nixon writes the following in his Memoirs:

As I worked with Bill Safire on my speech that weekend I wondered how the headlines would read: would it be Nixon Acts Boldly? Or would it be Nixon Changes Mind? Having talked until only recently about the evils of wage and price controls, I knew I had opened myself to the charge that I had either betrayed my own principles or concealed my real intentions. Philosophically, however, I was still against wage-price controls, even though I was convinced that the objective reality of the economic situation forced me to impose them.

The public reaction to my television speech was overwhelmingly favorable. On the networks, 90 percent of the Monday newscasts were devoted to it, and most of the focus was on the brilliant briefing that John Connally had given during the day. From Wall Street the news came in numbers: 33 million shares were traded on the New York Stock Exchange on Monday, and the Dow Jones average gained 32.93 points.

Anyone with a brain, of course, was horrified at the unfolding of events, doubting their legality and predicting with great precision the coming disaster of shortages and mass confusion. They achieved nothing but to suppress the inevitable as enterprise was crushed. The inflation eventually roared back like a pot full of water with a lid and the burner still running.

Nixon absolutely knew better but it did it anyway. He defended the decision in his memoirs even as he said his policy was wrong. Try to make sense of this:

What did America reap from its brief fling with economic controls? The August 15, 1971, decision to impose them was politically necessary and immensely popular in the short run. But in the long run I believe that it was wrong. The piper must always be paid, and there was an unquestionably high price for tampering with the orthodox economic mechanisms…we felt it necessary to depart dramatically from the free market and then painfully work our way back to it.

So there we go: rationality took a back seat to political expediency. Nixon was in a panic but is Kamala? They keep telling us that inflation has cooled to the point that it is nearly gone. Why, then, is she engaged in this plot to impose nationwide price controls? Maybe there is panic going on behind the public facade? Maybe this is just a longing for extreme executive power over the whole country all the way down to our breakfast cereal? It’s impossible to know.

It is even too much for the Washington Post: “When your opponent calls you ‘communist,’ maybe don’t propose price controls?”

One strange effect of the talk of price controls now is to incentivize landlords to raise rents now before new controls come into effect after the inauguration. This is perhaps why we are starting to see rental contracts with lower per-month rents at 7 months rather than 12 months. Presumably starting next year, residential rent cannot be increased more than 5 percent per year. On average over the last 4 years, rents have gone up by 8.5 percent per annum, which means that the difference has to come from somewhere.

In the short run, it can come from dramatic increases now in rents. In the long run, the difference will come in the form of reduced amenities, repairs, and services of all sorts. When the equipment at the gym breaks or the pool closes for cleaning, you could be waiting a very long time for it to be repaired if ever. The experience in New York City – or, for that matter under Emperor Diocletian in ancient Rome – shows precisely what results: shortages, property and service depreciation, and business closures.

What’s deeply troubling about the Nixon presidency is that he knew it was wrong and did it anyway. What’s even more troubling about the Kamala Harris case is that it is unclear whether she even knows it is wrong. Perhaps that should not shock those of us who have lived through times when the health officials acted like natural immunity doesn’t exist, that we didn’t have therapies for respiratory infections, that masks work, and that two weeks of comprehensive closures could ever be constrained to that time period.

We seemed doomed to watch the same old errors unfold before our eyes, in a natural trajectory of folly from money printing to inflation to price controls, just as from universal quarantines to growing ill-health, education losses, and population demoralization. May the gods save us from more rounds of the same before it is too late.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.