On March 20, 2020, Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York uttered the following in defense of his “New York State of Pause” executive order:

“This is about saving lives and if everything we do saves just one life, I’ll be happy.”

This was received by many, especially in the media, as proof of his compassion and great leadership. In reality, it was proof of exactly the opposite; only a morally bankrupt man would utter those words. If he uttered these words cynically then he was being rhetorically manipulative to exploit the fact that many contemporary humans have substituted sentimentalism for actual moral thinking.

If, however, he meant them sincerely, then he subscribes to one of the basest forms of the moral framework known as consequentialism and he would be able to justify nearly any atrocity that he found politically expedient.

If we are to avoid a repeat of the moral crimes of lockdowns and mandates, we must understand the dangers of consequentialist thinking in public health and be able to formulate a valid moral structure that serves the actual common good.

What is consequentialism?

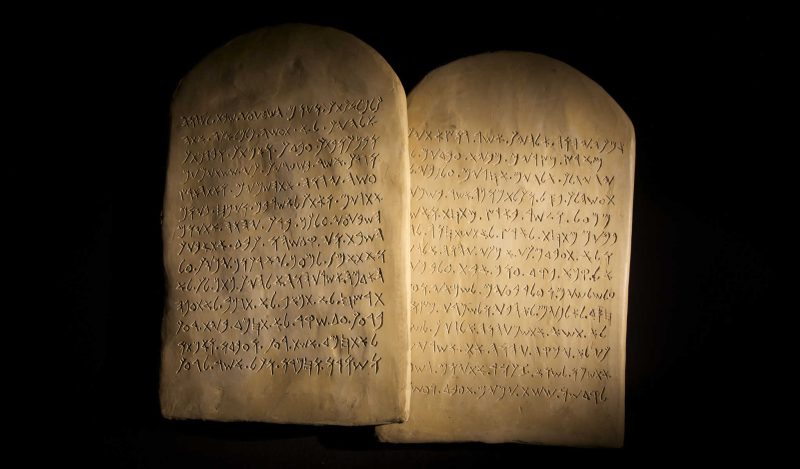

In summary, consequentialism is one of the various modern projects to create a system of ethics that does not require grounding in Divine Law or the Natural Moral Law. Rather than beginning with a list of a “Thou shalts” and “Thou shalt nots,” it is instead suggested that one apply the simple rubric that any action which has more good consequences than bad consequences is a good moral action and any action which has more bad consequences than good consequences is a bad moral action.

The difference between this ethical theory and others is demonstrated by one of the classical hypothetical moral dilemmas: if killing and harvesting the cells of a single infant can save one million lives, is it morally permissible? Consequentialism is forced to answer yes; murder is thus deemed justifiable.

The dangers of such moral thinking was set forth by Pope St. John Paul II in his 1993 encyclical Veritatis Splendor. He right observes that

…the consideration of these consequences, and also of intentions, is not sufficient for judging the moral quality of a concrete choice. The weighing of the goods and evils foreseeable as the consequence of an action is not an adequate method for determining whether the choice of that concrete kind of behaviour is “according to its species,” or “in itself,” morally good or bad, licit or illicit. The foreseeable consequences are part of those circumstances of the act, which, while capable of lessening the gravity of an evil act, nonetheless cannot alter its moral species.

Moreover, everyone recognizes the difficulty, or rather the impossibility, of evaluating all the good and evil consequences and effects–defined as pre-moral–of one’s own acts: an exhaustive rational calculation is not possible. How then can one go about establishing proportions which depend on a measuring, the criteria of which remain obscure? How could an absolute obligation be justified on the basis of such debatable calculations? (77)

Let us remember that the people making calculations about the good and bad effects of lockdowns and mandates had laughably ridiculous ideas about the dangers of Covid. One poll suggested that Americans believed that 9 percent of the country had already died of Covid by July 2020. Even the most sincere and well-intentioned consequentialist would be left unhinged by such an outright hallucination!

Traditional Morality and General Rule

Traditional Christian morality teaches that a moral decision is licit if and only if the three fonts or sources of the act are good or at least neutral. These are: “the object chosen, either a true or apparent good; the intention of the subject who acts, that is, the purpose for which the subject performs the act; and the circumstances of the act, which include its consequences” (367).

Unlike with consequentialism, there are some actions which are always wrong even with good intentions and beneficial consequences: “[they are], in and of themselves, are always illicit by reason of their object (for example, blasphemy, homicide, adultery). Choosing such acts entails a disorder of the will, that is, a moral evil which can never be justified by appealing to the good effects which could possibly result from them” (369).

Such hard and fast rules are absolutely necessary for us humans who are often guided by a combination of our passions and defective reasoning. For example, Adam Smith recognized as much in his Theory of Moral Sentiments where he observed that general moral rules are nature’s answer to the human capacity for self-deceit:

This self-deceit, this fatal weakness of mankind, is the source of half the disorders of human life. If we saw ourselves in the light in which others see us, or in which they would see us if they knew all, a reformation would generally be unavoidable. We could not otherwise endure the sight.

Nature, however, has not left this weakness, which is of so much importance, altogether without a remedy; nor has she abandoned us entirely to the delusions of self-love. Our continual observations upon the conduct of others, insensibly lead us to form to ourselves certain general rules concerning what is fit and proper either to be done or to be avoided. Some of their actions shock all our natural sentiments. We hear every body about us express the like detestation against them. This still further confirms, and even exasperates our natural sense of their deformity. It satisfies us that we view them in the proper light, when we see other people view them in the same light. We resolve never to be guilty of the like, nor ever, upon any account, to render ourselves in this manner the objects of universal disapprobation.

We humans need to have rules formulated before we face the passions of the moment. We must intend never to break these rules no matter how expedient it might appear in the heat of the moment. In the heat of the moment we may not be able to remember why theft, adultery, or murder are wrong but it is essential to remember that they are wrong. Consequentialism does not allow for such rules.

The Fall of Public Health and the Future

Public health fell before any of us noticed. Those of us who fought against lockdowns and mandates from the beginning have rightly observed that all our pandemic planning documents had largely ruled out these measures. These things were not ruled out on solid moral grounds but rather they were ruled out due to their high perceived cost combined with their lack of demonstrated efficacy.

This left open a loophole that, if we get scared just enough, we might be able to justify doing them anyway. When everyone is losing their minds, it doesn’t matter that we were right that they wouldn’t work and would do a bunch of harm. All we get is the most unsatisfying “I told you so” of our lives.

Instead, we need to focus on creating a list of “interventions” that should be off the table regardless of the alleged severity of the pandemic du jour. Very early on, I had argued that the lockdowns were objectively immoral because it is never permissible to prevent the working class from earning a living for themselves.

The once non-negotiable obligation of “informed consent” has been obliterated by lying propaganda and coercion; did anyone who received mRNA shots have full information and fully free consent?

Civil society in general and public health specifically needs a list of “Thou shalts” and “Thou shalt nots.” Without them, any evil imaginable can be justified when the next panic hits. If we want to avoid a repeat of 2020 or, God forbid, something even worse, we must make it clear what we will never ever do, no matter how scared we might get. Otherwise, the siren call of “just saving one life” may lead us to previously unthinkable evils.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.