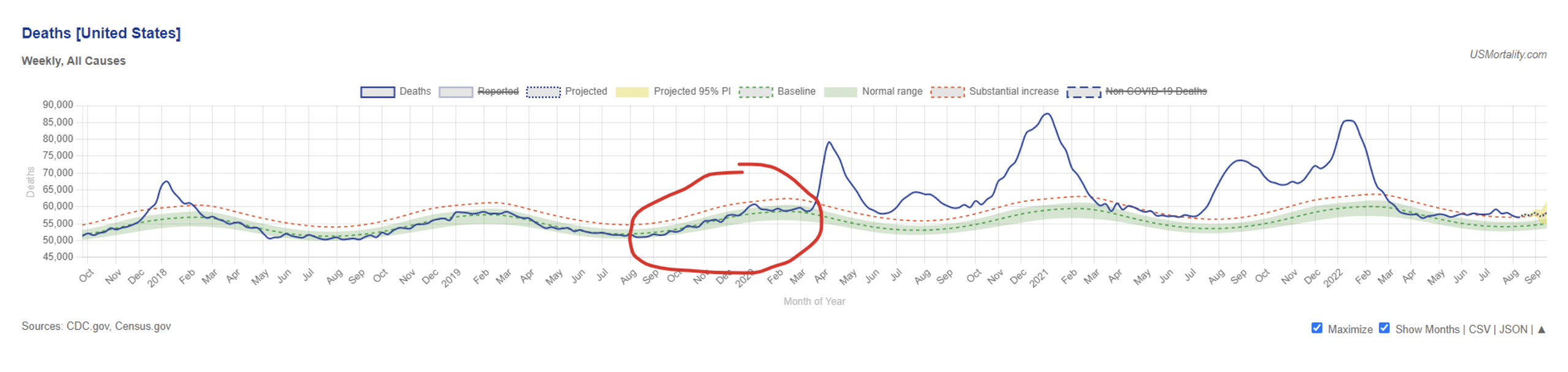

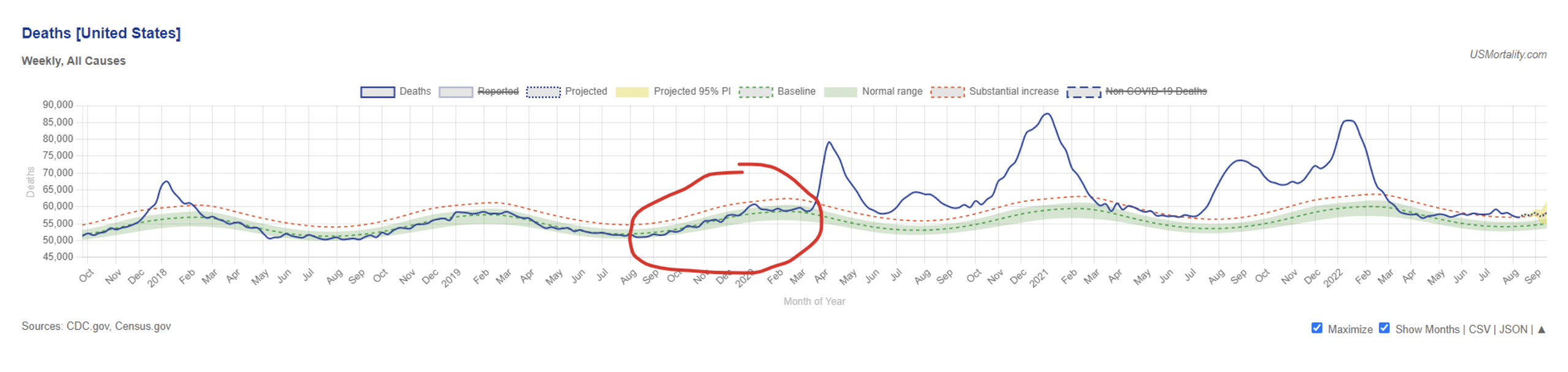

There is now no shortage of evidence that the coronavirus had begun spreading undetected all over the world by autumn 2019 at the latest. However, the 2019-20 flu season was mild in most places. For instance, here is U.S. mortality, with the 2019-20 flu season circled.

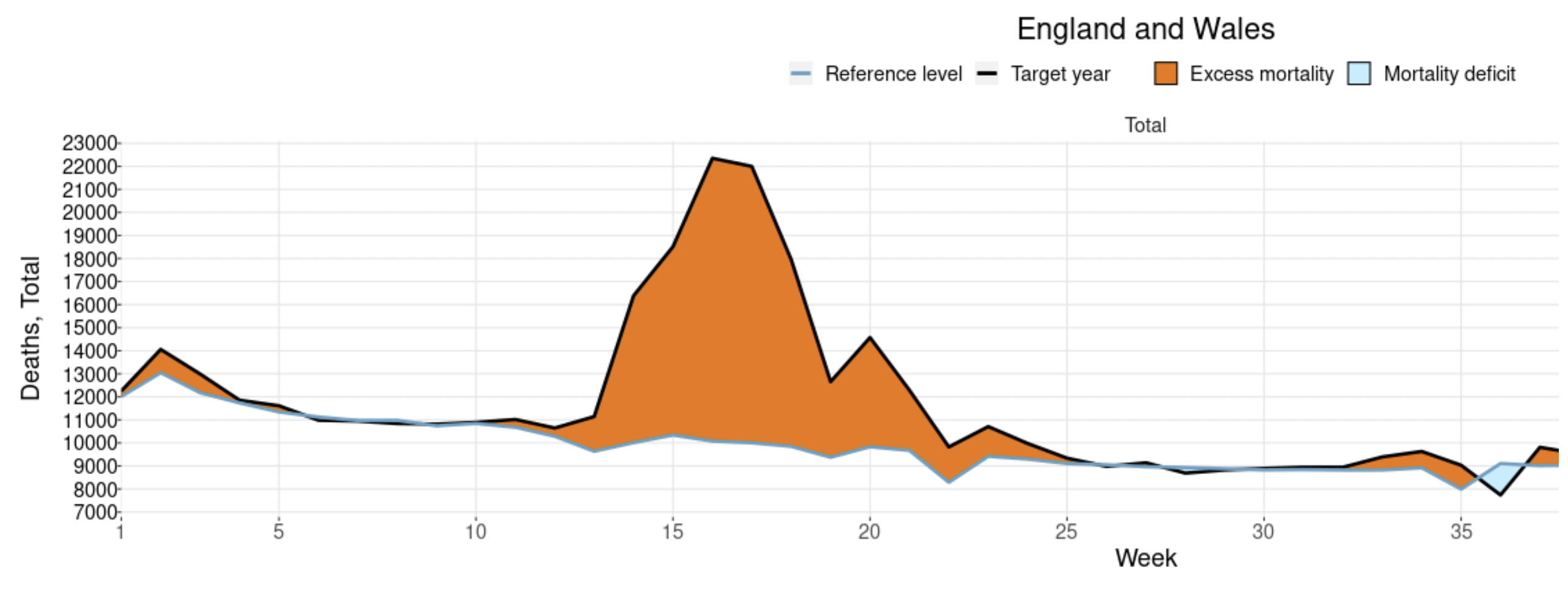

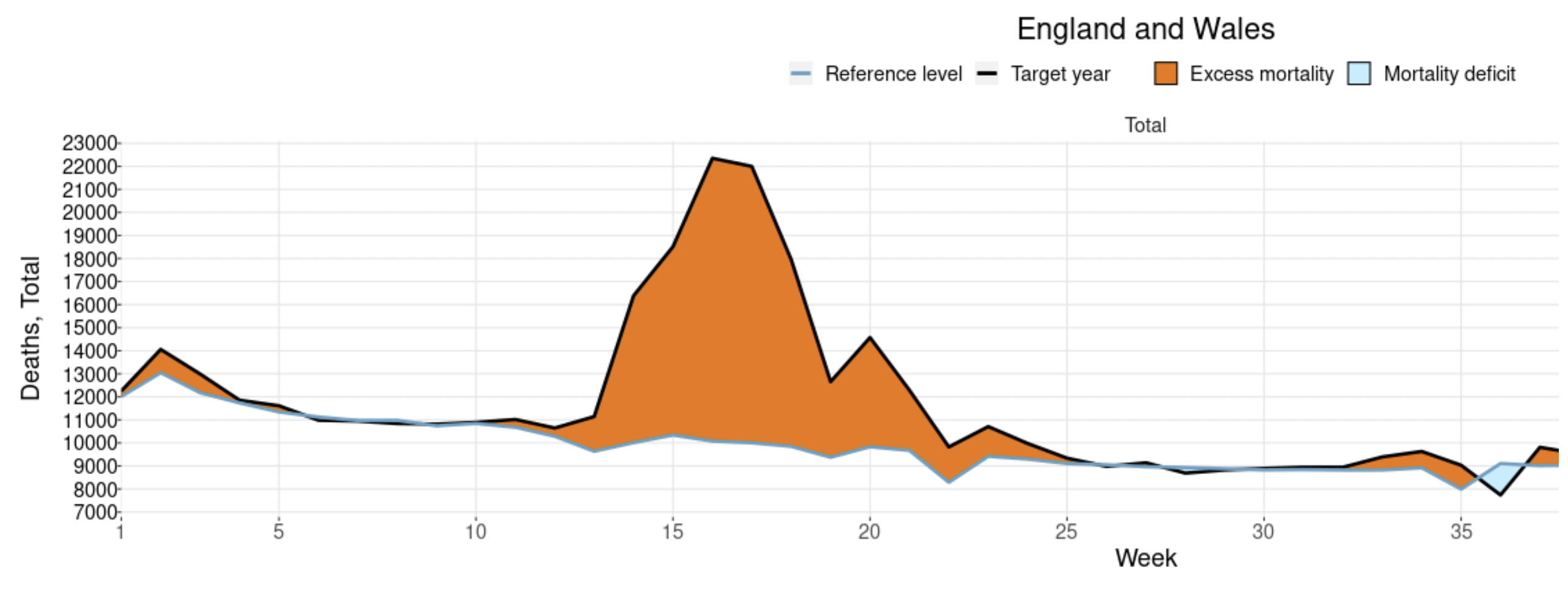

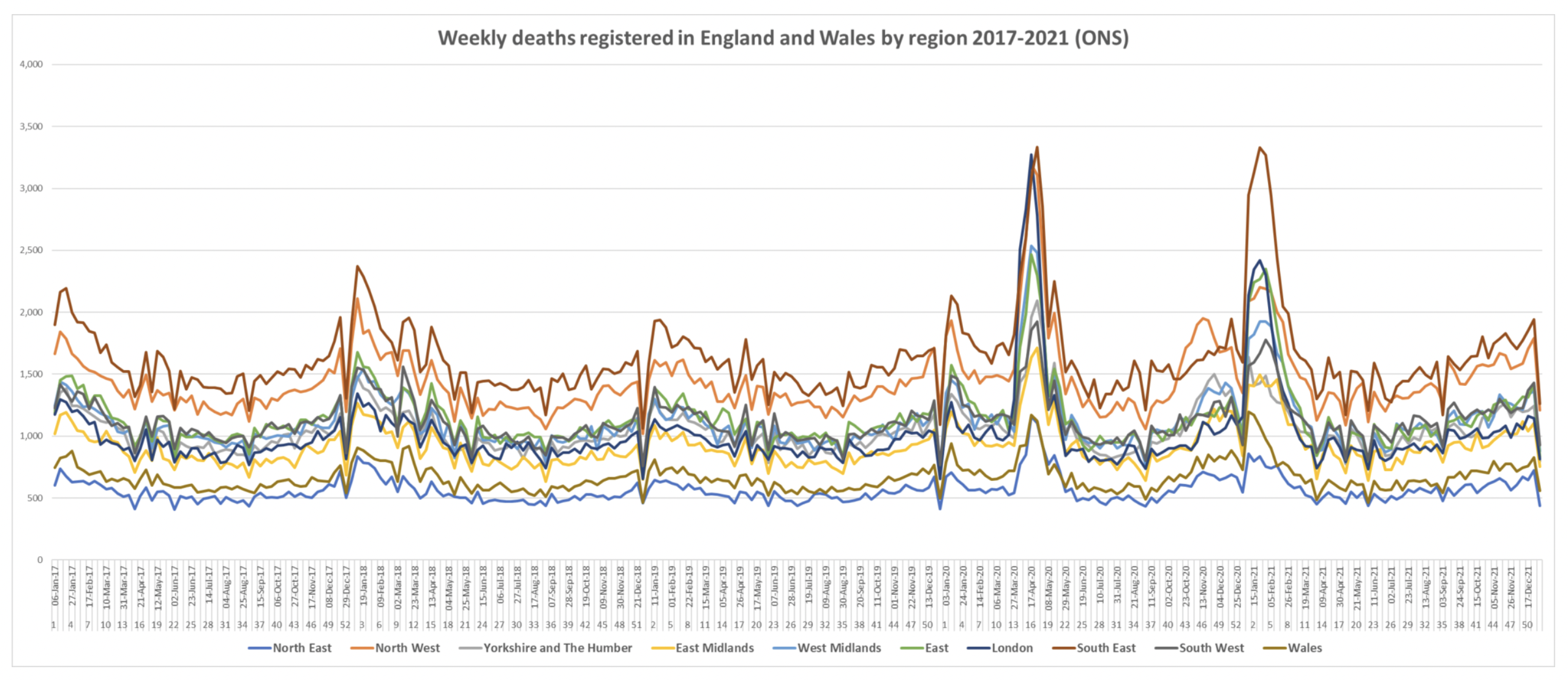

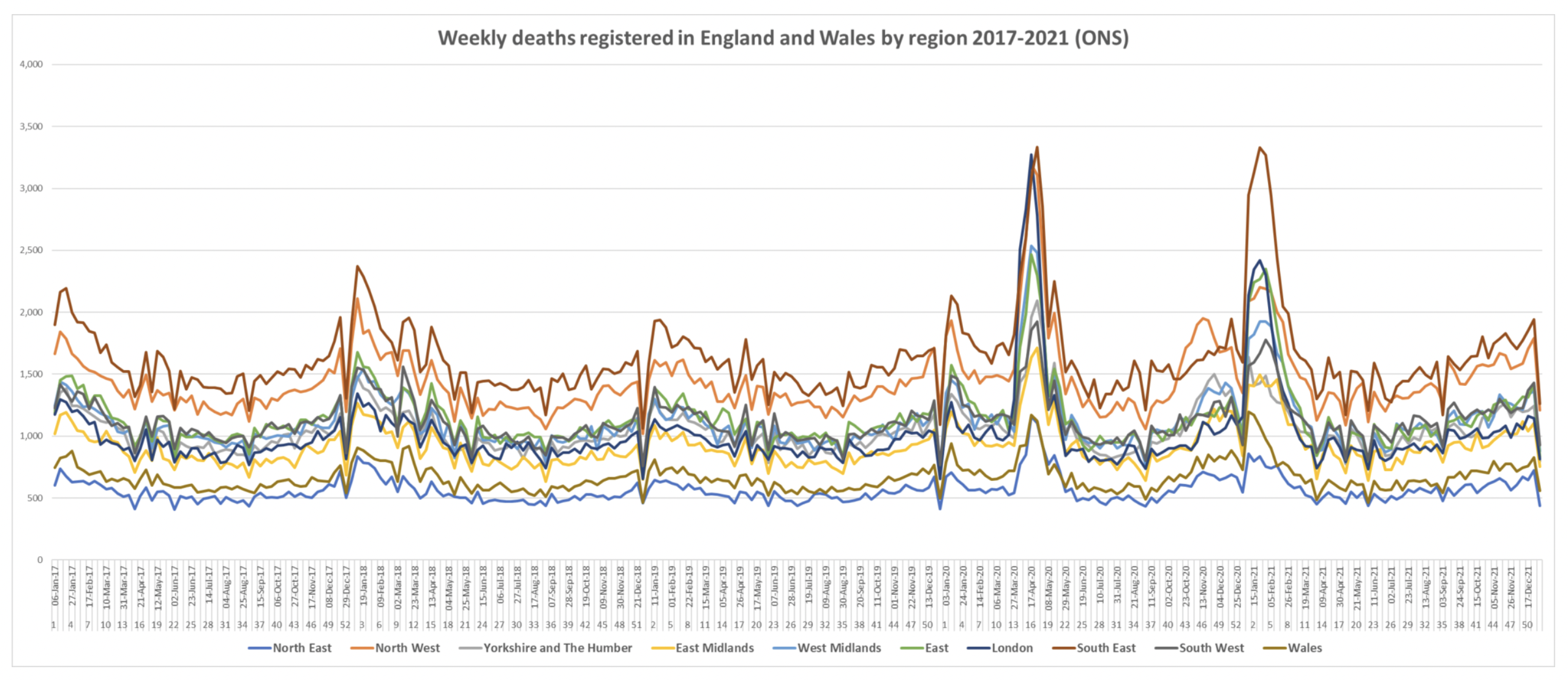

And here is England and Wales, with the unremarkable end of winter 2019-20 on the left hand side (before week 10). The contrast with the spring surge (and subsequent waves) is obvious.

This leads to a mystery: why did COVID-19 only start killing lots of people come spring 2020 if it had been hanging around quietly all winter?

Some sceptics argue that it’s because Covid isn’t really a more severe virus than flu, but the excess deaths were all caused by how we started responding to it in February and March 2020. For example, the overuse of ventilators particularly in New York City and the surrounding states in the first wave has been suggested by some to account for tens of thousands of additional deaths. However, while a ventilator panic in and around NYC will explain some of the additional deaths that spring, it wouldn’t explain the deadly outbreaks elsewhere, or the deadly outbreaks that kept coming in subsequent waves even as the use of ventilators was scaled back.

The fact that deadly Covid outbreaks kept coming over the ensuing months and years (see the U.S. chart above) is a powerful objection to the idea that what was causing most of the deaths was anything peculiar about the treatments used in, say, New York in March 2020. After all, many states including Florida had deadly waves during summer 2021 as the Delta variant surged.

But Florida had not had a large wave the previous winter (despite famously ending its statewide restrictions in autumn 2020). It’s clearly not the case that medics in Florida started going big on the ventilators again just as Delta appeared, and then stopped using them again afterwards.

This is not an adequate explanation for the patterns of deaths we see. Early on there was a high level of variation in how many deaths occurred in different U.S. states, just as there was in different countries, for example, between Eastern and Western Europe. However, over time the number of excess deaths tended to converge, putting a limit on how much of the variation can be pinned on things specific to localities or time periods, such as poor treatment protocols early on in the north-eastern United States.

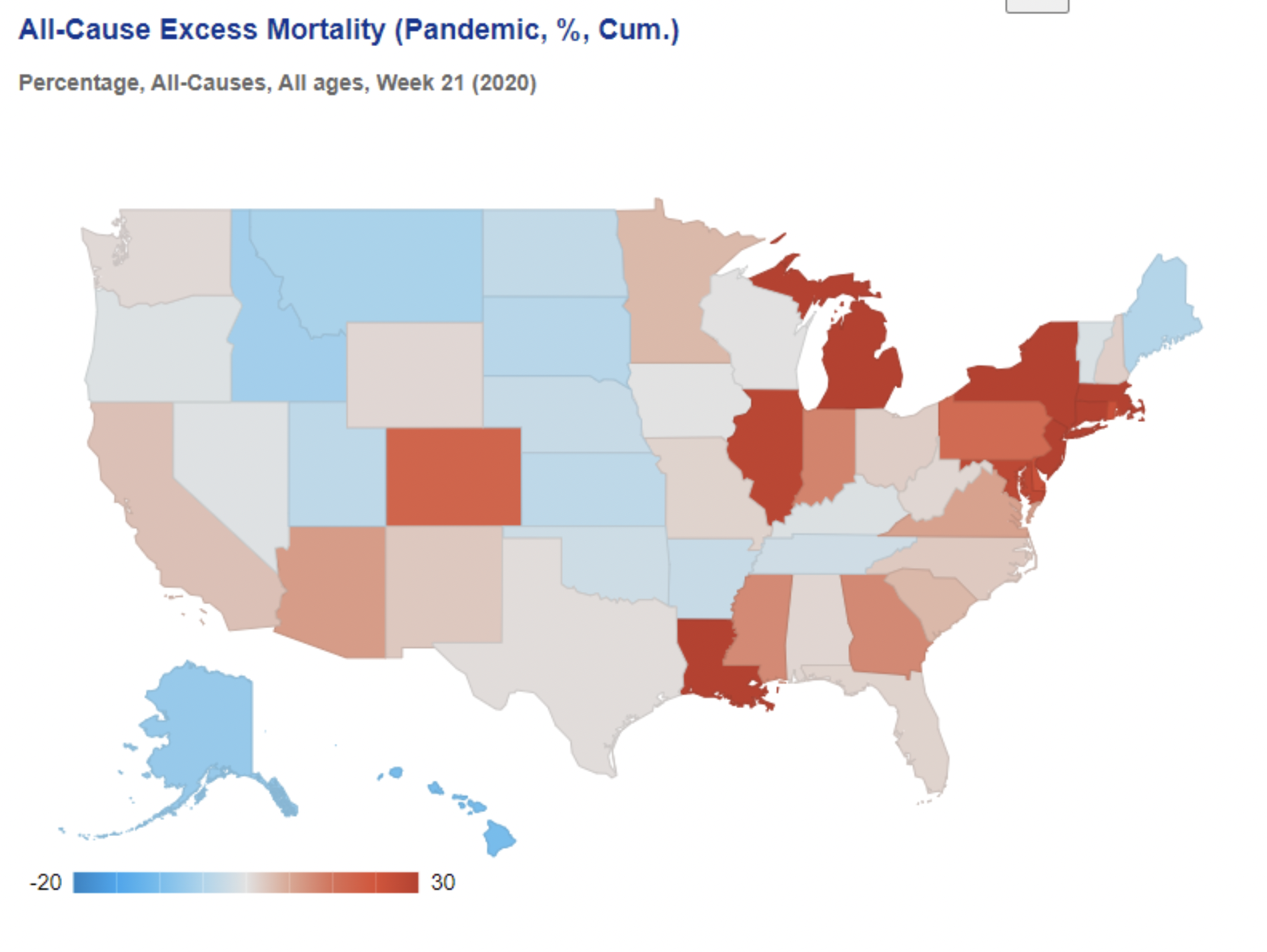

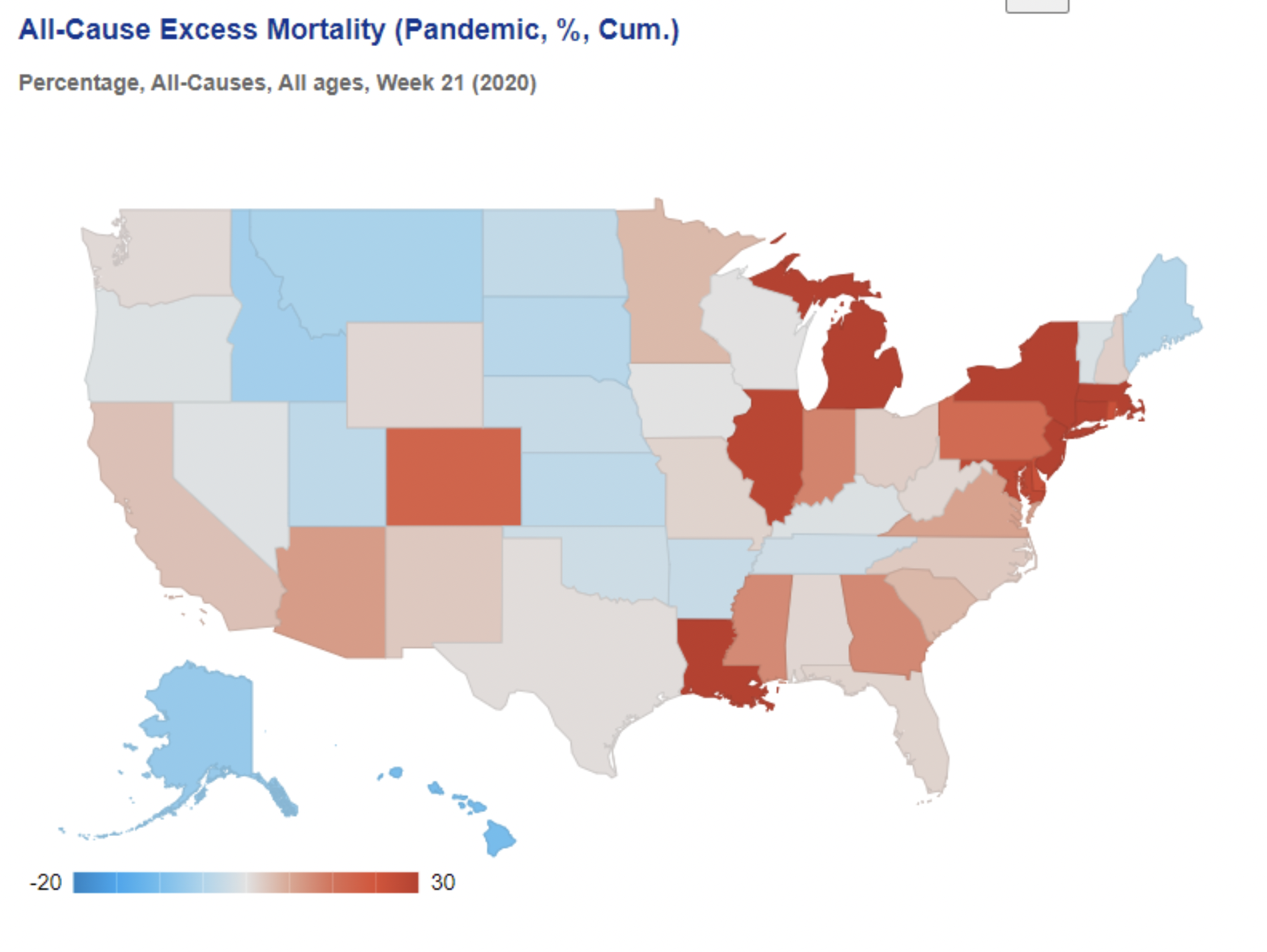

Below is the picture in the U.S. at the end of May 2020 – a real patchwork, though with clear concentrations of excess deaths around New York and around Michigan, Illinois and Indiana, plus Louisiana and one or two other states.

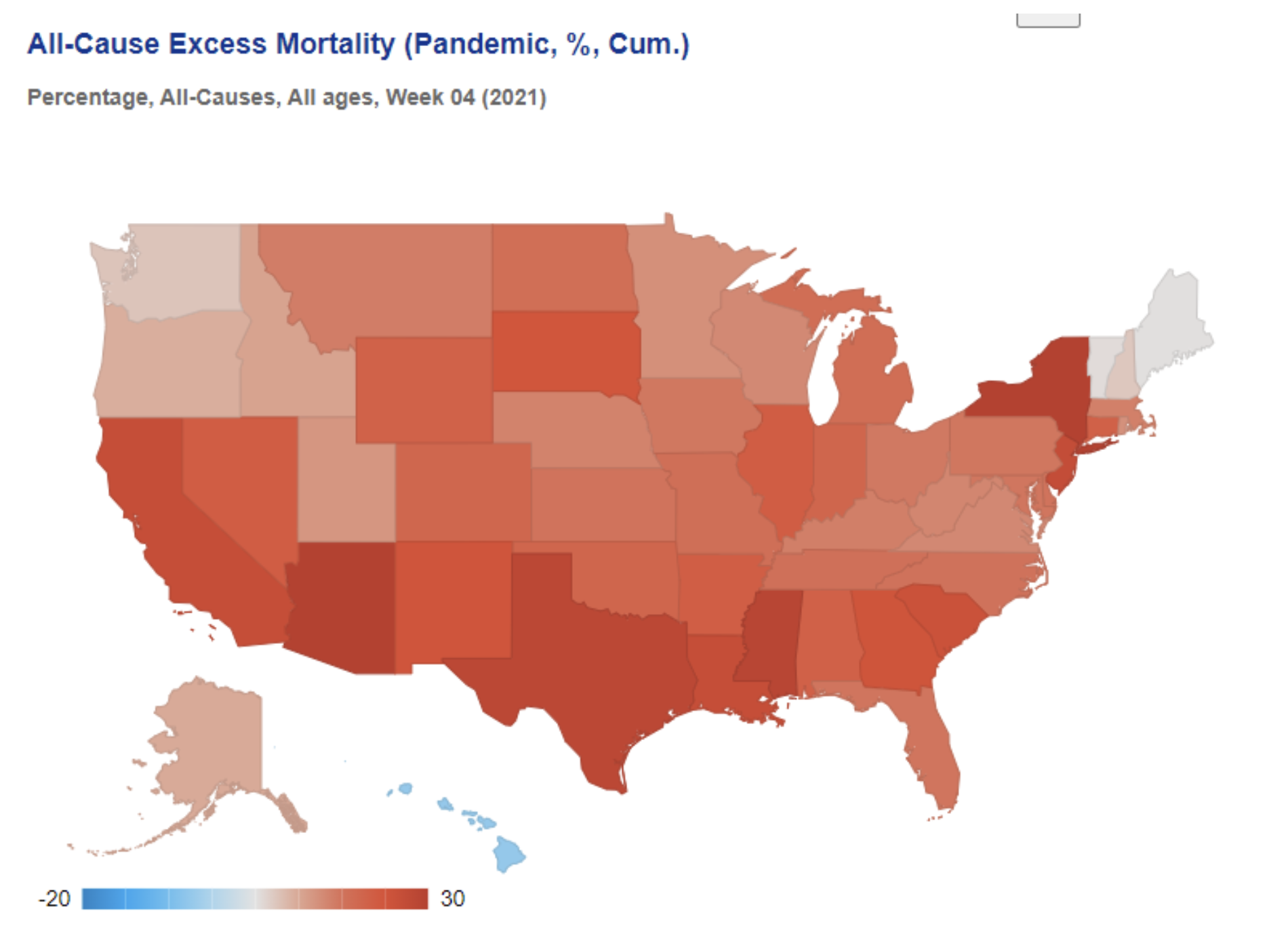

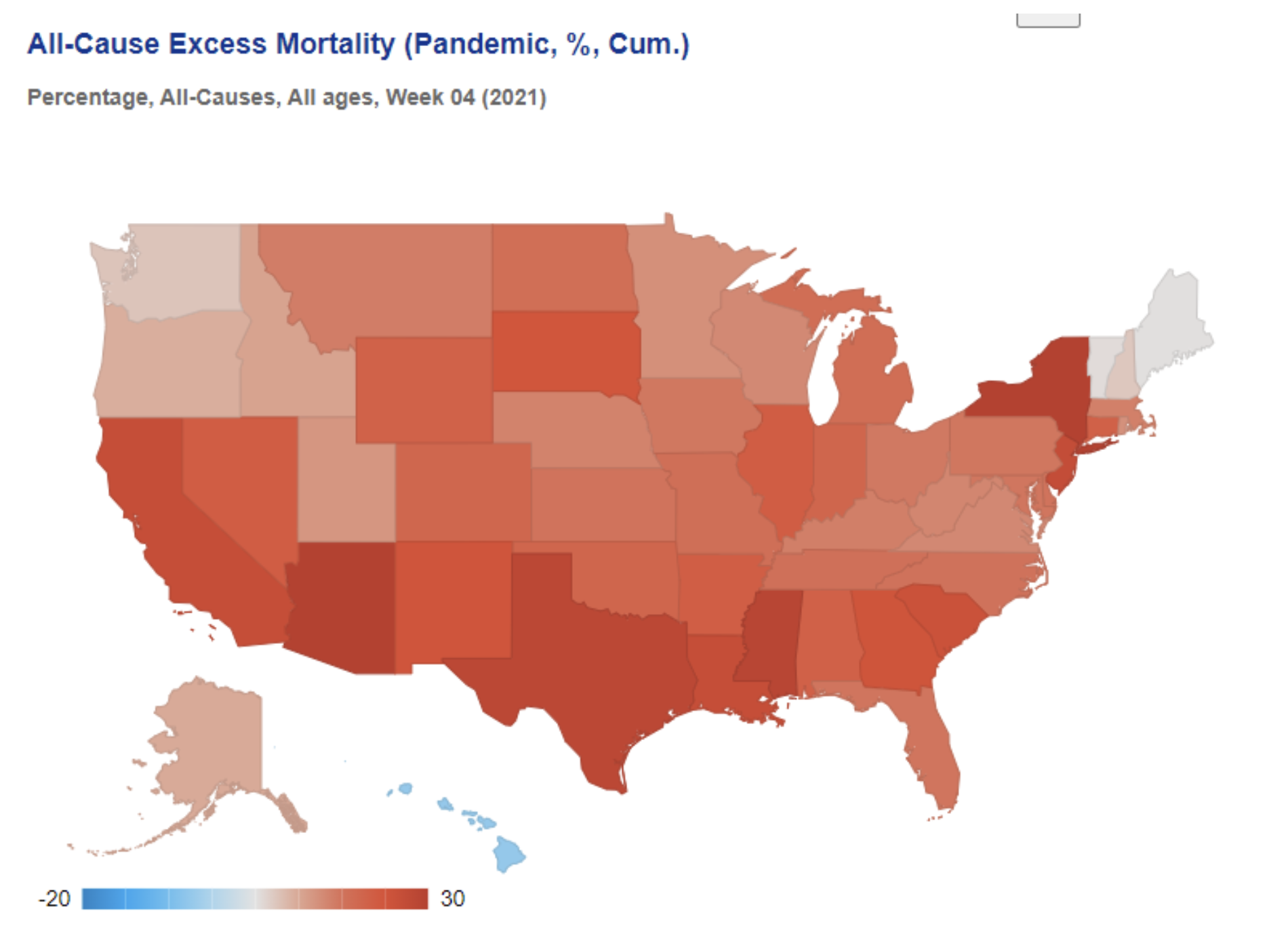

By the following winter, however, excess deaths were high almost everywhere, meaning specific local treatment protocols or policies cannot be blamed for bringing the deaths.

One suggestion is that the simultaneous surge of deaths across the regions of England in March 2020 is indicative of a cause other than an infectious virus. However, data from the ONS, displayed below, suggest that flu deaths typically surge across the country simultaneously, so this is not unusual or unexpected. While the data below are by registration date, which creates artificial synchronicity (e.g. from bank holidays – the sharp dips), nonetheless the regional patterns are so tight they leave no room to think the picture by date of occurrence would be vastly different.

In other words, the main driver of Covid deaths appears, in fact, to be COVID-19, a disease caused by a virus which Dr. John Ioannidis has estimated from antibody surveys to have an infection fatality rate (IFR) of around 0.3-0.4% in Europe and the Americas. This rate, he says, varies between and within countries and over time, and some of that variation will be due to poor treatment protocols. However, the consistency of the values across different contexts suggests this is the right ballpark, at least for those with no specific immunity to the virus and pre-Omicron. Dr. Ioannidis writes:

Even correcting inappropriate exclusions/inclusion of studies, errors and seroreversion, IFR still varies substantially across continents and countries. Overall average IFR may be ~0.3%- 0.4% in Europe and the Americas (~0.2% among community-dwelling non-institutionalised people) and ~0.05% in Africa and Asia (excluding Wuhan). Within Europe, IFR estimates were probably substantially higher in the first wave in countries like Spain, U.K. and Belgium and lower in countries such as Cyprus or Faroe Islands (~0.15%, even case fatality rate is very low), Finland (~0.15%) and Iceland (~0.3%)… Differences exist also within a country; for example within the USA, IFR differs markedly in disadvantaged New Orleans districts versus affluent Silicon Valley areas. Differences are driven by population age structure, nursing home populations, effective sheltering of vulnerable people, medical care, use of effective… treatments, host genetics, viral genetics and other factors.

But if a virus with an overall IFR of around 0.3% was spreading throughout the winter, why were deaths so low until March and April?

I had thought this may be due to a more deadly variant emerging in, say, Lombardy and spreading to New York and elsewhere. However, it is now clear to me that the main reason for the lack of deaths was the lack of spread, particularly in care homes. Yes, the virus had spread around the world, but it had not displaced flu and the other viruses, and did not have any explosive outbreaks. It just moved around at a low level alongside other viruses, infecting some people but not in huge numbers. This may seem strange given what has happened since spring 2020 and the series of large waves with explosive surges and no flu anywhere to be seen. But the evidence on this is completely clear, as summarised below. Winter 2019-20 was an ordinary winter, despite SARS-CoV-2 lurking and circulating incognito.

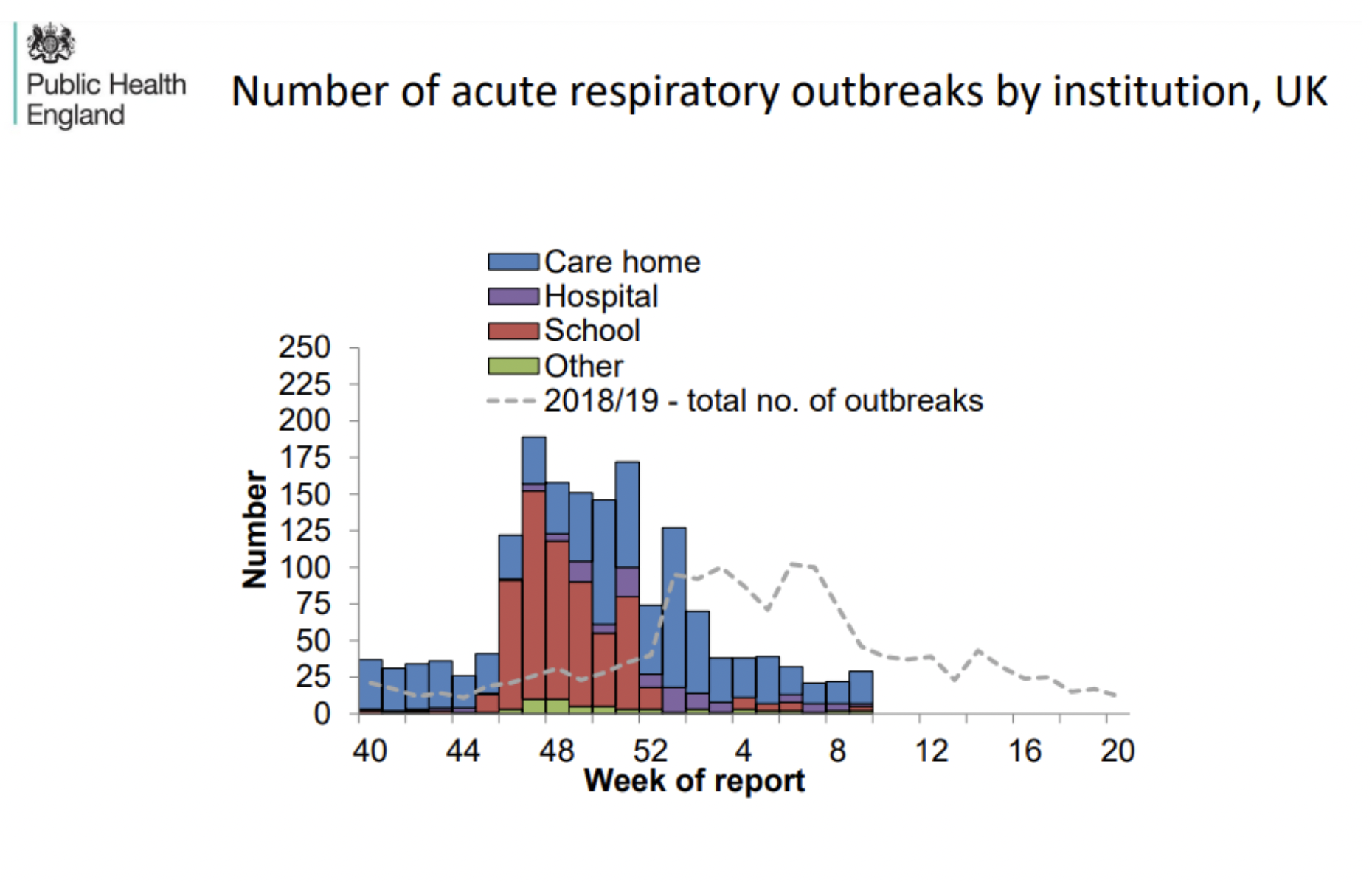

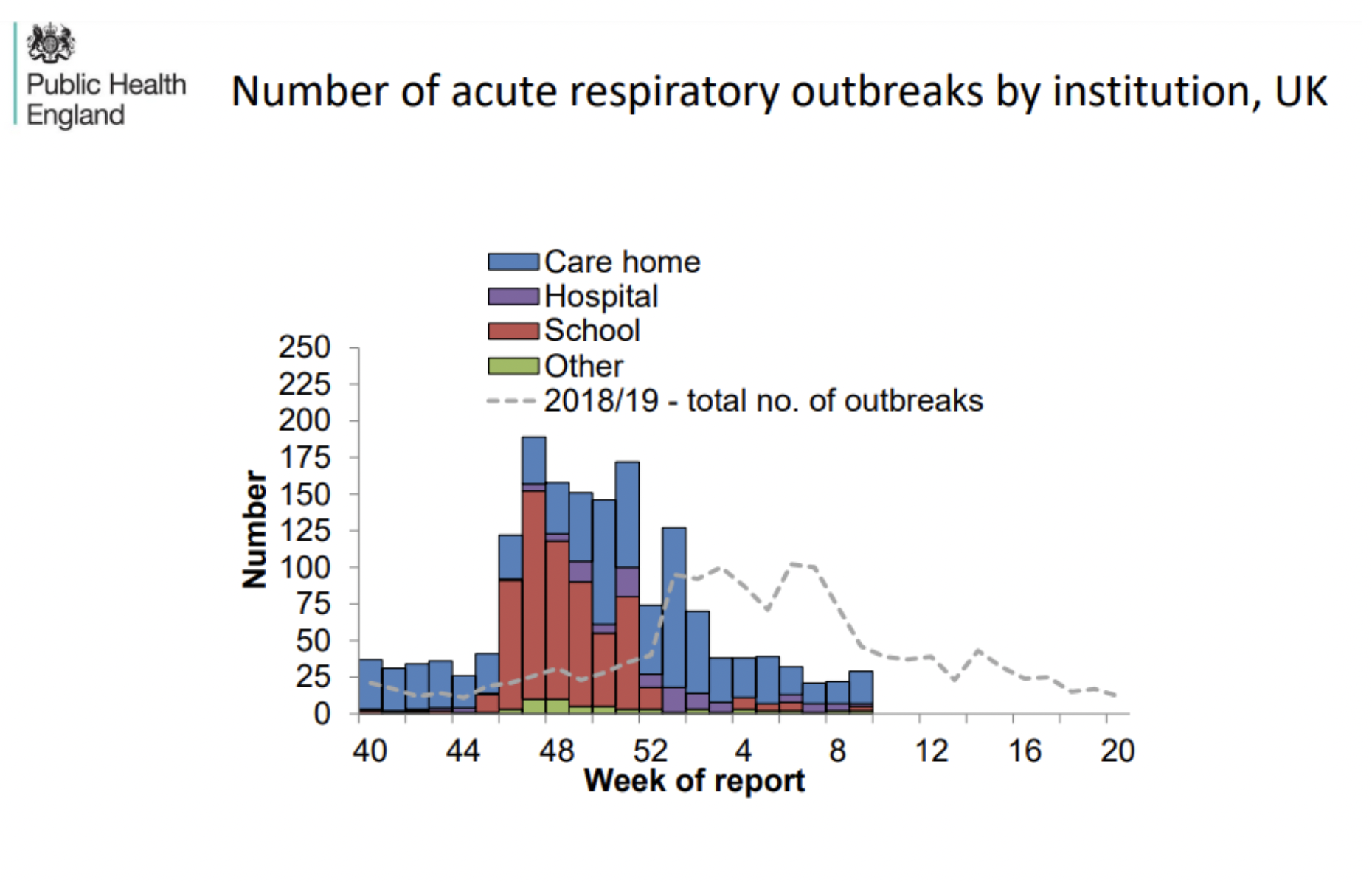

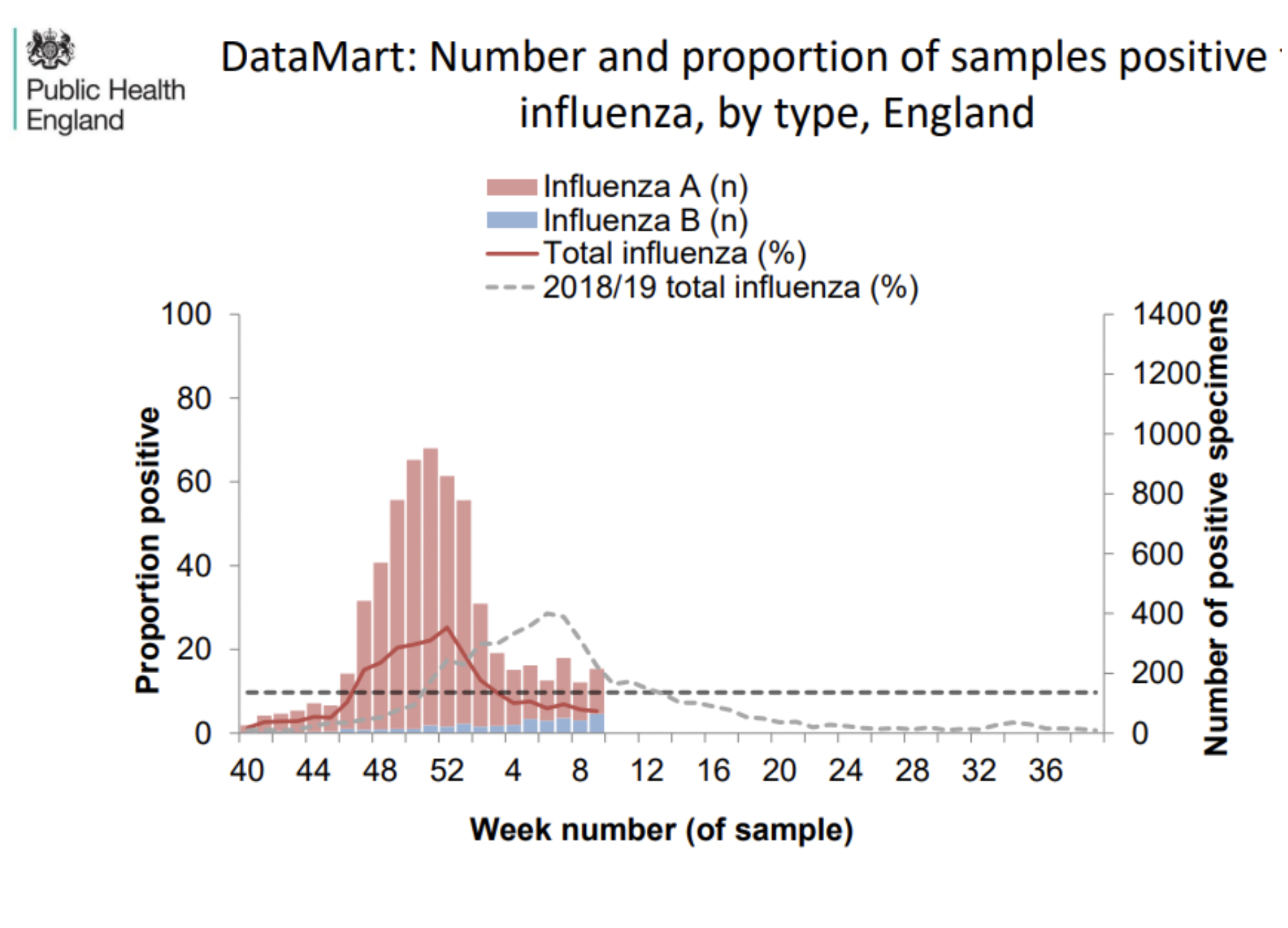

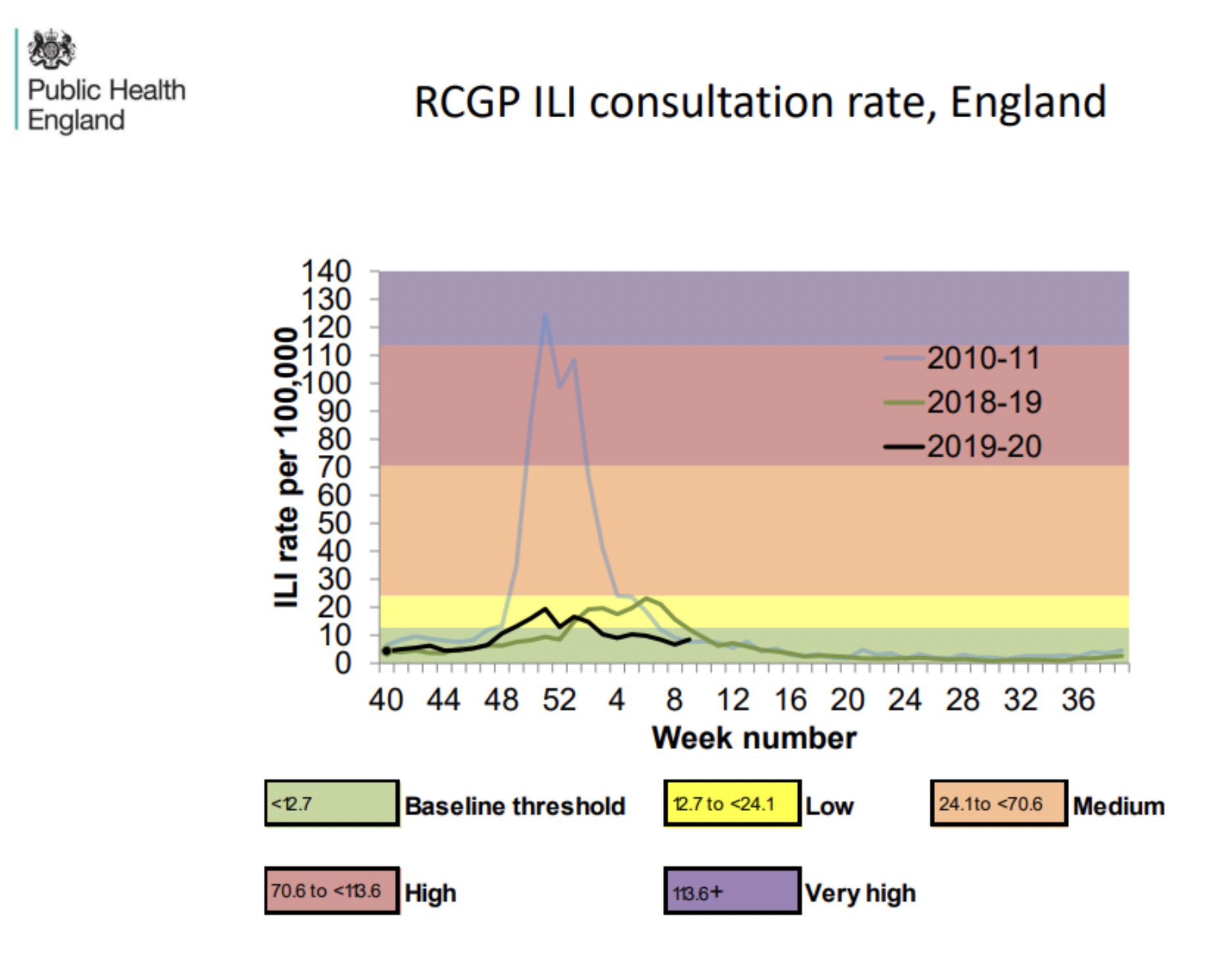

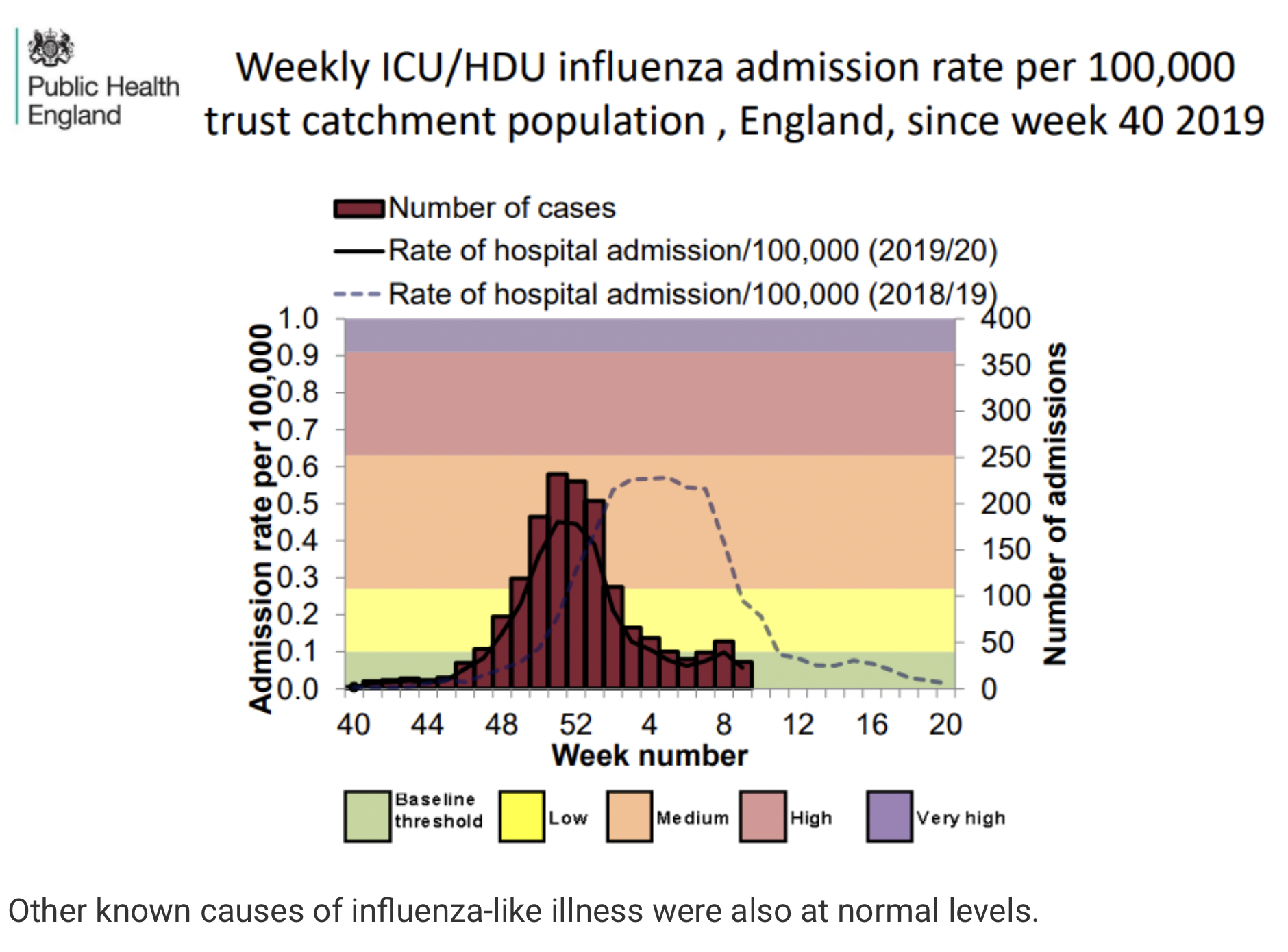

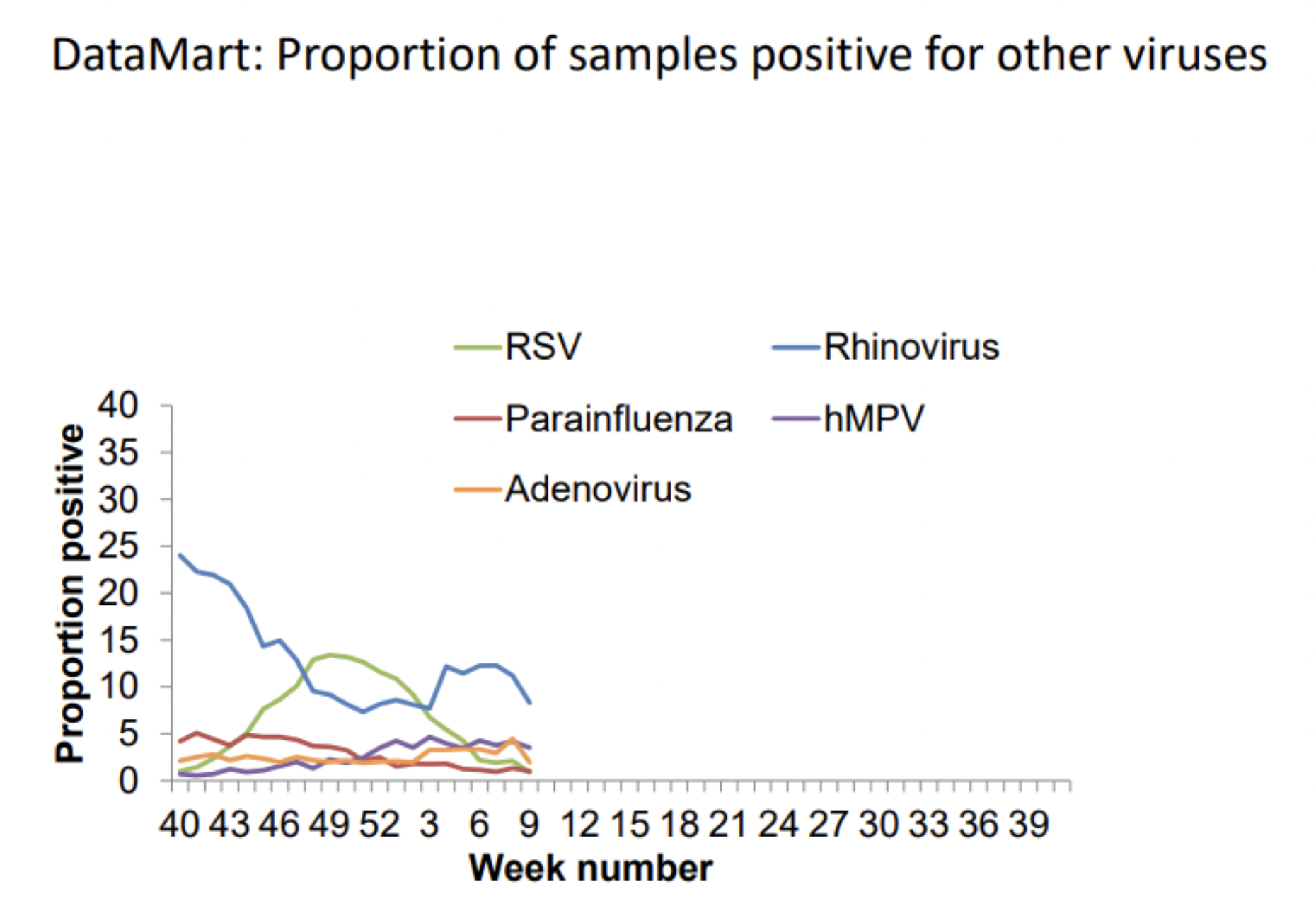

Take a look at these charts from the U.K. flu surveillance report in early March 2020. The flu season arrived early but it was not particularly severe.

The proportion of influenza-like illness testing positive for flu was normal, if early.

GP consultations for influenza-like illness were normal.

ICU admission rate for confirmed flu was also normal.

Other known causes of influenza-like illness were also at normal levels.

While many hospital tests for the cause of influenza-like illness came back, as usual, for an unknown pathogen – one of which would have been SARS-CoV-2, of course – the proportion for SARS-CoV-2 couldn’t have been that high as overall deaths were not, as we have seen, elevated as they would have been if SARS-CoV-2, which has a higher IFR than flu (~0.3% vs ~0.1%), was rife.

This limited spread of SARS-CoV-2 that winter is also confirmed by early antibody testing. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya’s antibody survey of Santa Clara County in California on April 4th-6th 2020 found 2.8% of the population with antibodies. This puts an upper limit on how many of the general U.S. population can have been infected during that winter.

Antibody evidence from England also shows a low level of spread throughout the winter before an explosive outbreak at the end of February. The following chart was created by researchers who asked those who tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies when their symptoms began (these were antibody tests, no PCR tests or LFTs were involved). The pattern of infections it gives is striking – and supports the picture above of a virus circulating at low level over the winter before suddenly going big.

So the evidence all points to a picture of SARS-CoV-2 being widespread in the winter of 2019-20 but not being the dominant virus, circulating at a low level, before exploding into a large outbreak – and getting into the care homes – in the spring. It was thus this explosion in spread that primarily caused the explosion in deaths (though some were caused by poor treatment protocols of course, and a sizeable number of care home deaths were due to mistreatment of residents). The deadliness of the virus didn’t change a great deal; the IFR didn’t suddenly leap up; it’s just that suddenly many more people were catching it and spreading it, and it was getting into many more care homes. (Discharging hundreds of infectious hospital patients into care homes to free up beds won’t have helped with this of course.)

So why did the virus suddenly become much more infectious in February 2020; why did it go from circulating at a low level alongside flu and other viruses to displacing them and infecting a relatively large proportion of the population in a space of weeks? What’s more, it has stayed in this infectious mode, with successive variants driving new surges and waves. Though not everywhere, notably. In some countries, such as Japan, South Korea and other East Asian countries, it remained in its low-spread pre-2020 mode until Omicron came along (which has so many mutations it is a substantially different virus).

So why? This, I think, is one of the big outstanding mysteries of the virus. Why is its behaviour at different times and places so variable, so hard to predict? My feeling is still that this has a lot to do with the genetics of the virus and how it interacts with the genetics and other features of the populations it infects. Variants, in other words. Not more deadly variants necessarily (though Omicron is significantly less deadly than earlier variants). But variants that are more transmissible among certain populations, or certain sections of the population. After all, new waves are often caused by new variants, which seem to be able to infect (or re-infect) a different group of people to the previous ones. So why couldn’t the first big waves also be explained by a similar shift in variants?

Thus what may have happened in February 2020 is a new more transmissible variant emerged (or at least more transmissible among certain subgroups of people) which was then able to spread much more readily. But for some reason it wasn’t able to become dominant everywhere at once, or get into care homes everywhere, thus the early patchwork of deaths, the staggered start, and also the gradual convergence.

Possible evidence in support of this is that one of the only interventions that some studies found to reduce deaths in the first wave was early border closures, which may be because it kept the new more transmissible variants out for longer.

Well, that’s my current best guess. You might have a better one (though please don’t try to pin it all on the treatment protocols in New York or wherever, that really doesn’t explain what we see). But whether my guess is right or wrong, the question of why a virus circulating over the winter at a low level suddenly started spreading fast and wide and causing successive waves of deaths is not yet resolved. The virus still keeps its secrets.

Reprinted from The Daily Sceptic

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.