Gigi Foster, economic professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, is co-author of The Great Covid Panic (Brownstone Institute, 2021) and a fierce opponent of lockdowns and mandates that have caused so much damage to Australia’s economy and long-standing tradition of human rights. Jeffrey Tucker of Brownstone interview her in this detailed interview, as her book is growing in influence in Australia and around the world.

She explains her views and reveals how much of her life has been changed by being such a public proponent of opening up society. “I don’t know if I’m going to be embraced back into the community of economists in Australia ever, in the same way,” she says.

“I’ve got people who absolutely hate my guts. Won’t go on to debate with me. I’ve had multiple appearances where the host tries to find someone who will be there with me and kind of provide a counterpoint and nobody will do it. They ask multiple people, they won’t do it. People hate me. People see me as literally the devil.”

We are posting the Rumble version with anticipation that the YouTube version is likely to be taken down.

Jeffrey Tucker:

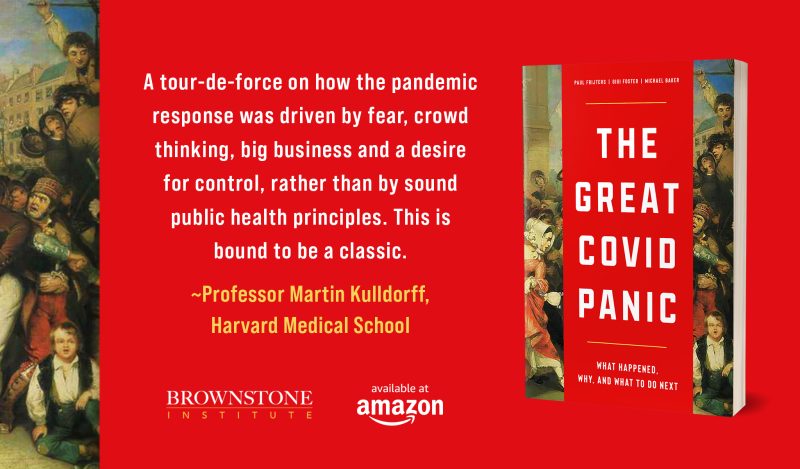

Well, I think the recording has already begun, so I should just introduce you as Gigi Foster at the University of New South Wales, Professor of Economics and the co-author of this glorious book. I’ve held this book up a hundred times. That is so good, right?

Gigi Foster:

Here is mine.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Look at you. Yeah. Is your edition the same as mine, even though you’re on the other side of the world?

Gigi Foster:

It’s same edition. It’s the same edition, but I have some markings because I’ve been doing in-person book launches here with readings and stuff. So, I have little sections that I like to read depending on the audience and the mood and what we’re talking about, it’s useful.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, tell me which sections you like to read the most?

Gigi Foster:

I tell you that the Crowds chapter seems to be the most impactful for many people, because they just haven’t thought about the crowd dynamic, previously, because we haven’t observed it really, in our lifetimes, most of us. Or we sort of learned about crowds, but I never really thought it could apply to our lives today, so I think that is really a useful one. And also, people like to hear about the scale of the tragedy, just from a very objective standpoint. What have lockdowns done to us. What have we lost, not just in the developed world, but in the developing world, so that’s useful.

Sometimes, the political economy just generally unto the Middle Ages analogy, the analogy to feudalism in today’s sort of way in which corporations and governments collude and sort of control populations more than we might think they do or then you would think, if you aren’t analyzing it. And also the bad macro section, that’s one that’s popular. And I like that one because it’s basically taking a direct aim at some of the people within the academy, my colleagues, unfortunately, who have just gone right along with his madness and been apologists for it. And it illustrates the corruption of science during this period, from a very personal standpoint, because obviously, all three of us are economists. And we’ve seen some of the worst rationalizations. I mean, worst in the sense of most offensive and non-aligned with the goals of economics in normal times, coming out of our discipline.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right, it’s a bit of a shock, which is I think one of the reasons that when I first read the manuscript, I think it was that section on Crowds that affected me, too, the most. Although today on the Brownstone website we ran the General Section against lockdowns, which is actually very strangely calm. It was like well lockdown sounded intuitively correct, but the history. There are at least two obvious problems and one slightly unobvious.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah, at that.

Jeffrey Tucker:

I was surprised at just how weirdly calm that section is. Because like lockdowns are a massive violation of every principle of liberalism, as we think about it, as and so that section is like dial backing, right? You were very patiently explaining.

Gigi Foster:

Well, I mean, we thought that was necessary because we were just surrounded by people who have bought into the lockdown ideology. And they will have in their minds, a very facile sort of reason why lockdowns should work. And so, we addressed that very directly in that section as you know. We say, “Look, on the surface of it, the idea is that you prevent people from interacting with each other and therefore, transmitting the virus. That’s what people believe. That’s what they think when they think lockdown, they think, “That’s what I’m doing.”

But they don’t realize how many other collateral problems are happening and also how little that particular objective is actually being serviced, because of the fact that we live in these interdependent societies now. And we also are trapping people often in large buildings, sharing air together, and not able to go outside as much and so we’re actually potentially increasing the spread of the virus, at least within communities, our communities. So, it basically is an example of trying to engage with the people we feel are misguided on this issue in a calm way, not screaming at each other, not sort of taking the radical position on either side and just saying, “I’m going to play gotcha with you” because that’s not productive.

To move forward, which we want this book to help us do, as societies, we need to start being able to talk to each other more about these really important issues and engage with each other. I mean, that is also one of the principles of classic liberalism. You have to be able to investigate and try new things, experiment and engage with each other respectfully and be open. And not get stuck in the mud and into routines and with just some narrow monovision that you disobey, you get ostracized from the group. That’s just not the way to develop a healthy society. So, we do think that that kind of effort is important.

And yes, it is frustrating. It was difficult. Some chapters were hard to write in that calm way because, I mean, obviously, all three of us are absolutely, just deeply offended and incredibly angry. And we’ve got in the depths of despair like I’m sure you have as well as seeing the destruction during this period. And it’s just, it’s heart rending, heart rending. And so, we also felt we could get some of that emotion out through the stories of Jane and James and Jasmine. I do put a bit of it into the chapter on the tragedy where we talk about the cost of these lockdowns. But in terms of the scientific presentation, we try to keep the emotion out of it.

Jeffrey Tucker:

I thought about running the whole section on Jasmine because she looks like your description. Because it’s basically autobiographical, right? I mean, yeah, so I like that. Let me just back up a little bit because one of the things that struck me as why the whole book is important, because if you just read it in isolation, you only get a piece of the thing that matters.

But I liked your chapter on viruses and immunology and immune systems, too because one of the things your whole section on lockdown builds up. You’re like, “Well, this is not practical. Maybe you can avoid the pathogen if you lock down. Maybe.” But that’s not how we’ve chosen to live and that’s not the reality of the world. But there’s a slight problem with that too, because then you get this naive immune system problem, which is potentially more deadly, even more than governments.

Gigi Foster:

Right. Absolutely. No, I mean, and you read a piece on the Brownstone Institute about how great natural immunity is and how it is basically one of the fundamentals of Virology in terms of Virology 101, you learn about the importance of a natural immune system, and that is our main primary defense against pathogens in general. And we’ve just sort of forgotten that that exists during this period, in terms of our policy responses. And indeed, lockdowns have a number of really negative effects on people’s immune systems, right?

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yeah, I know.

Gigi Foster:

I mean, we had to separate from other people. We’re not outside. We’re not getting the sunlight. We’re not having exercise as much. We are more stressed, so we eat things that are worse for us. And all of those things we know are bad. Plus crowded out healthcare for preventative kinds of visits and like screenings and also acute problems, which could also hurt us. So, there’s just all sorts of damage that we do to our society’s immune systems when we lock people down. So yes, I mean, that was an interesting chapter to write as well, because for us, it was very straightforward. It was sort of like this, “Here’s all this knowledge that seems to have been forgotten in the fog of war, so let’s just put it on the page. All right? Just, let’s remember who we are here, right?”

Jeffrey Tucker:

This is pretty scary from a scientific point of view. So much for the Whig view of history, the view that that world is getting smarter and better.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah, I don’t know. I mean, it’s interesting, because I have had some conversations during this period with people asking me, “How is it that everybody has become so dumb? It’s like the entire general IQ has just plummeted, right? And I think there’s several things to say about that, obviously. One of them is that we have seen the Flynn effect in operation before now, anyway, right? So there is this sort of gradual potential slide in IQ, which happens when we have some of the influences on ourselves that we have today that we didn’t have, say 30 years ago.

Certainly, I would say social media and the influence towards reduction in length and depth of thought that our environments have. People talk about obesogenic environments. I mean, there’s got to be a term for environments that generally decrease and depress your ability to think. And so, that I think has definitely been the case. But I would also say that, in my observation, the correlation between IQ and sensemaking, during this period has been virtually zero.

Jeffrey Tucker:

I agree with that. It sometimes seems actually maybe the reverse, right? I mean, so one of the things I’ve observed is that, typically it’s the ruling class or the upper class that the most educated people who have been the most in favor of lockdowns, but that may be a class interest issue. It may not be an intelligence issue, but there is, there does seem to be some, I mean, you can’t prove this, but some relationship between high intelligence and high stupidity on the matter of lockdowns.

Gigi Foster:

There’s a couple of things going on there. One, I think you’re right, yes. Their self-interest is properly understood and the ability to be a James in your own area, basically. To be able to make advantage for yourself out of this tragedy. And then that drives the incentive to come up with beautiful rationalizations. Apologies for why whatever is being done should be done. I mean, that’s the purpose of our big brains anyway in our everyday lives, right? Rationalize what you already wanted to do.

And that has been on display, enforced during this period. And of course, these are the people with a big brains, so they got even bigger and better and more beautiful rationalizations that it takes more cutting analysis and depth of thoughts to counter. And also, people are vulnerable to the influence of the crowd no matter what their IQ is, right? Plenty of people in crowds of the past have been smart people. It’s not like this somehow attracts only the dumb, right?.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, that’s, I mean, arguably the ruling class has gotten even a smaller interest group, a community of influence than say working class, which you tended to meet more people in that sort of thing.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And also they’re very coddled really in their modern lives, right? That’s been another problem. A lot of the elite are in this, as you call it, the laptop class, right? And there have been the ones making the policy and they have been essentially, through the various ways in which we live now and what status brings to you in terms of your lifestyle. They’ve been protected from any of the risks that used to be just completely de rigueur in our lives.

And the people on the street who are, the truckies or the people cleaning the roads, or the repairman or whatever, they are used to taking risks kind of as a normal part of life anyway, and they’re close to the reality. They’re right there at the coalface and so, they just don’t have the luxury of being able to wring their hands over a virus that is at 99.9% recovery rates. And for which there is now early treatment, and all these other things, right? And to actually stop society, plus, they’ve got the back pocket reason as well, which is they need the money to survive. They don’t necessarily have the big bank balances that many of the laptop classes have been able to rest on during this period.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right. Yeah. This is a long tendency of and I wonder if it’s a potential problem for, the problem of freedom itself and democracy and equality, that there is a long history of the ruling class or the upper classes or the upper tier of society, to imagine themselves to be both clean and deserving of a greater degree of cleanliness than others. So, you get these kind of caste systems or I mean, this is true in the deep south during slavely. ed, not worthy of temple and needed to be cleansed by a rabbi. And even apparently, in Ancient Rome, there is a tendency to just otherwise sandbag, the merchant class and the working class.

Gigi Foster:

Definitely. And I mean, that’s really interesting, too, because it shows how culture is a product of economic circumstance. And in this case, circumstance related to health. I mean, it is just true that really nasty diseases can sometimes pass more easily in dirty environments and that means that yes, there is a risk there. Now, it’s not as extreme as obviously it’s being depicted, but it certainly is something that’s real. And then once you sort of hook into that as a culture and make it part of your ideology, it can be extremely divisive.

And we start to then see these sorts of very exclusionist ideologies come up that are also very conveniently in the service of keeping the elites or the top class segregated from the unclean, right? And of course, so then a mechanism of power retention. So, it is this really interesting combination of factors that really are about culture responding to the circumstances of the organism, so.

Jeffrey Tucker:

And it profoundly impacts on the problem of economic liberalism and liberalism generally, because we need to really come to terms with the problem of infectious disease and the impact that’s had on social structures, social and political structures throughout history. But what’s fascinating to me, Gigi, is that, that I don’t think that this would have been a problem that would have occurred to me until this pandemic. I mean, this has sort of revealed something to which, I said, about which we hadn’t really, least for me, I hadn’t really thought that much about.

Gigi Foster:

I will say, yeah, I have thought about it in a slightly different flavor, which is the modern ideology of prudishness. So, something that that really seems to have come along, I wouldn’t say really, as far back as the Romans. The Romans were very non-British by modern standards. But sometime in the sort of Renaissance type of time, enlightenment time, we started to see this more of an emphasis on things like modesty and properness of behavior. And we had the Victorian era where everything was very proper, right. And even now, we have separated bathrooms from men and women. We don’t have sex in public. We don’t do certain things in public anymore, that would have been considered just kind of normal 2000 years ago.

And so, I did, I have thought about that. And my co-author, Paul Frijters and I have certainly considered why that would be. And one of the sort of running theories, I guess, that we have about why that might be the case is that at a certain point in the development of industry, it became very advantageous if you could concentrate for a long time on a particular type of specialty. Become really, really good at doing something. And that was much more convenient, much more, much more easy to do if you were able to block out distractions, like there goes that pretty girl or there’s that naked guy or whatever. So, if we establish a norm of prudishness, so that it’s sort of considered proper not to do certain things in public then it creates a situation or an environment where that kind of specialization becomes easier for the individual to manage.

And then of course, specialization according to comparative advantage is one of the big pillars of industrial development. And so, we’ve seen that more and more and more. And we do see prudishness more even now amongst the elite sorts of classes. If you go into any truck stop or whatever, you’ll see pictures of naked ladies on the walls and stuff or in a repair shop, you’ll see that. There’s much less kind of angsty self-sitting kind of ideology around our core primal needs amongst those sorts of people and then those sorts of occupations than there is amongst the laptop class. But I certainly hadn’t considered it as an extension to a broader point about uncleanliness and sort of what is inappropriate to do about.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right. So, you have this interlocking relationship now between moral prudery and biological cleanliness. And that all comes together with the vaccines, right? So, if you get the shot that makes you clean and it makes you also a good person, it makes you smart. If you don’t get the shot then you’re dirty and you’re stupid.

Gigi Foster:

Well, that and a danger to society.

Jeffrey Tucker:

And a bad and immoral person. So all this is coming together, it’s like this big crash and it’s hard even to talk about it because people just absorb these messages and blend them all into a big mush.

Gigi Foster:

Isn’t it amazing? Isn’t it amazing? I mean, the human brain is just the most amazing thing. I mean, I find it, it’s so easy for me to get up in the morning be motivated, because I just find it unendingly fascinating how incredible our brains are. And one of the great, one of the amazing things about them is that we have this capacity for extraction, which just allows us to do so many things. Which no other animal can possibly conceive of doing. But at the same time has the potential to lead us down the garden path, as they say, in Australia. To go off the rails really badly.

Because when you and I say something, some abstract thing like say liberalism or freedom or something, you and I may think that we are in full agreement about what that thing is and what it means the implications. We have a whole little mental model about that abstraction in our heads. But I can guarantee you that the model, the actual specifics of the model in each individual person’s head, who is saying the same abstraction is different. And so at the same time, that abstraction allows us to unite as a people, we also have this ability to kind of develop different ideas about what it really means.

And then sometimes those fractious tensions come out in the open. And so we can say to each other, “Yeah, when I said cleanliness, I didn’t mean have a vaccine and have this and have that.” But somebody else really did, right? And so, and then talking about it becomes difficult because we thought we were united, but “Oh, no, right?” So, yeah, again, we need to work out how to communicate with each other despite the fact that we have to use abstraction to communicate. And those abstractions may not be as shared as we initially thought.

Jeffrey Tucker:

It just occurred to me that you’re talking about, we’re talking about whether and to what extent a person is vaccinated. One vaccine, two, three. The most clean person has like five or something like that. But isn’t it strange how we have a confession culture, too, right? So, everybody has to reveal this. And I’ve been asked this all time in interviews, “Well, have you had the vaccine?” I’m like, “I’m just not going to say.” We’re supposed to have had this sort of respect for privacy. That seems to be almost entirely gone.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah, I know totally. We have a little movement here in regional New South Wales, which is called “#notmybusiness.” And it’s actually by business owners. And the idea is that they are going against what the state has prescribed in terms of basically having a medical apartheid system where you’re not allowed to come into t he business unless you have vaccination proof, evidence. And they’re putting up on their storefronts, this #notmybusiness.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Nice, nice.

Gigi Foster:

And there’s a little video that goes along with it. And says, “We don’t believe in medical apartheid,” and all those sort of thing and the thing is that like any other kind of discrimination, discrimination based on the medical status is at the end of the day an extra cost on doing business.

And we know from discrimination studies in Economics, the economics of labor markets, where we’ve looked at discrimination, we know that if there’s even just one company that isn’t discriminating that company can eat the lunch of everybody who is discriminating because they don’t have to pay all the costs of keeping all the other people the unclean out, right. And so as soon as you allow for just a little bit of that then there should be market forces that kick in to assist the rejection of these damaging discriminatory policies.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Let me ask you, it’s a very interesting question, because I know a lot of people are going to be listening who are Americans that they know now that you’re living in Sydney. I mean, you’ve been there the whole time, right? So, I think Americans might have a tendency to otherize Australia’s policies in the full intent. And maybe I’m speaking about myself, but I found Australia’s policy of Zero COVID preposterous from the very beginning.

I was like, “Well, you’re a tourist country filled with intelligent people, why would you want to deliberately create by policy naive immune system for an entire country and thereby wreck your position in the world economy. And don’t you know that you’re going to be made a laughingstock of the world if you keep this up, because COVID is going to come to Australia.” I was looking at the case levels Australia, by the way. And they’re very, very low per capita. So, I think Australia is still going to, can expect a big wave unless there’s some cross immunities from SARS 1. I don’t know. But it looks as if Australia is yet to experience the pandemic.

So, I guess I had a tendency to sort of say, “Okay, what’s gone wrong among all my favorite wonderful people in Australia that they could have believed this?” But, I mean, there’s a couple of things about that. One is that US started with the Zero COVID policy in the early days. This is why Trump was driven to insanity and to lock us down because he kept seeing cases rise and rise and rise. It was like he didn’t want any cases. He wanted no cases. So, there’s that.

We started with a Zero COVID policy, but it was already here, so it was not possible. We had to back our way into some quasi rational position. The other thing is that, don’t you think it’s possible that we, Americans or really the world can get a bad impression of Australia, based just on the ruling class policies? There’s a lot of people who agree with you, right?

Gigi Foster:

Yes. No, There definitely are, but there’s also a very strong name and shame, a culture that’s come up that’s really made itself known during this period. And you’ve seen it in terms of what happened to me last year. When I spoke out, I was ridiculed and defamed on Twitter, even though I’m not even on Twitter. And I was called all manner of names, granny killer and neoliberal Trump cannot, death cult warrior, Yankee killer of whatever. I was likened to Ayn Rand, and all the [crosstalk 00:22:17] Genesis, all this sort of stuff.

And anybody who’s paying attention will sort of see that kind of behavior. And even if they disagree with a policy, so are they going to really speak up and just ask for that kind of abuse? No, they’re just not. And there is a culture in Australia of following authority and if you put that together with really, they have a very strong desire to be accepted by your group, which is where there’s make-ship kind of culture comes from, too. That combination means that a lot will just say it’s silenced in public.

Now, in private, yes, I mean, I’ve received thousands of emails from people and some of them the most sweet, heartwarming, full of gratefulness and gratitude and love and support. And just saying, “You’re our savior.” Have been likened to Joan of Arc, all these things. I mean, I don’t need to add anything more to my feel-good folder. It’s amazing what people have written to me, but in private, right? Because they are afraid of that kind of cancellation. I think the other thing that really, really assisted, unfortunately, in solidifying and locking in this political narrative of “we can keep COVID out” is the fact that we are an island nation, yeah.

And so, the politicians simply were presented with this possibility. It seemed very, very tempting, almost very seductive at the beginning of saying, “Well, yes, we can protect you from the thing you’re so incredibly frightened of, by locking us down, locking us away, right? We won’t let anybody else in.” So, it just plays right into that clean/unclean ideology. And once the politicians start playing that tune, it becomes extremely hard to change keys, because you backed yourself into a corner. And that’s why we ended up now having this vaccine hero story. And really no conversation at all about early treatments or randomized control trials for prophylaxis or anything.

I mean, we had ivermectin banned by the TGA. I mean, these crazy decisions, which, even if it doesn’t work, don’t ban it. Ivermectin is one of the safest drugs around. And so you just, you look at that and you just think, it is a response to what has happened in the political sphere here, which has been assisted by our existence as an island nation, just like New Zealand, unfortunately.

Jeffrey Tucker:

But New Zealand seems like a more extreme version of Australia, like Ardern, the other day. I think, it’s her name?

Gigi Foster:

Yeah. Jacinda Ardern.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yeah. Somebody asked her, said, “Look, I know you don’t want to think about it this way, but it seems almost and somebody could describe it that you’re trying to create a two-class society of the vaccinated and unvaccinated, the free and the unfree.” She said, “Yep, that’s exactly what we’re doing.” Did you see that interview?

Gigi Foster:

I didn’t see that interview, but it doesn’t surprise anyone that it’s absolutely offensive. It’s so offensive. I’ve had people sending me photos of just the signs on the walls and sort of shop fronts that says, “Proof of vaccination needed. All the welcome, proof of vaccination needed.” It is like 1984. This sort of, and Melbourne, of course, the clarion call was, what was it, “Staying apart keeps us together,” right. It’s Georg Orwell again, I mean.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, that was and the songs and everything, it was just a little bit much. And that was already the summer of last year when they’re doing all these, “Staying apart keeps us together.” Whatever the thing is. Now, what do you make of all the lockdowners investing everything in the vaccines, but now, it turns out and we learned this, I guess, of the summer, that the vaccines are, as they say, leaky, right?

So and now, we’re talking about boosters, and then even those are not quite doing the thing and so on and so on. So, my impression is that a lot of the proponents of vaccines really thought that this was going to be their way out of lockdowns. But now, it turns out that they are not, I’m not sure how widely understood that is. But all the data I’m seeing suggests that they’re not.

Gigi Foster:

Totally agreed, totally agreed. I mean, I think the most logical direction for things to progress is that as we learn about the vaccines’ fading protection, also potentially, nasty side effects and long-term effects we don’t even know about, I think the easier pivot will be towards something that is more efficient, and just less costly to enforce at a business point of call. And also in terms of vaccine passports or whatever. It just becomes too difficult.

So, I think maybe rapid antigen testing or testing on arrival, or something, a really quick sort of test, or proof of natural immunity through antibody tests or T cells or something that maybe you have to do once every six months, instead of having proof of the vaccine itself, we may go in that direction. And of course, we’re getting different vaccines and you never know, maybe in four or five months, we’re going to have another vaccine or the Covax vaccine that’s being developed here on the market, and maybe more people will be willing to have them because they’re using more traditional technology. And maybe that will help, but and they may be more long lasting.

But still, the cost, the incremental costs are constantly checking to see if everybody’s vaccine status. I mean, we can’t maintain that.

Jeffrey Tucker:

The other thing, Gigi, if I may say so and every time I bring this topic up, people want to shush me. But what about those who just have made the rational decision, maybe they’ve never been exposed to COVID, but they like a robust immune system and they’re willing to be a little bit under the weather for a few days? In exchange of which you get immunity, so…

Gigi Foster:

Yeah. It’s a touchy subject. I tend to agree with you, Jeffrey, I think that people should be free to put themselves into a situation in which they may risk being infected. I know that there is a kind of a moral argument against that, that is mounted frequently by, particularly people in the medical profession, who say, we would never want to be advocating for someone to voluntarily be infected with COVID.

Jeffrey Tucker:

But should people be free to live their lives normally, even without a proof of natural immunities, even without this?

Gigi Foster:

Yes.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Because based on an individual risk calculation, I’d rather take the risk of COVID.

Gigi Foster:

Completely agree with you.

Jeffrey Tucker:

That’s been my position from the beginning. I mean, like-

Gigi Foster:

Completely agree. Look for my personal life. If I were a queen, which I hope I never am and I hope nobody ever is, but if I were a queen then we would drop all of this stuff right now. We would open all borders. We stop all the testing. We stop all of this stuff. What we would do is protect people who are in the old care communities, aged-care homes, and we would be investing heavily in prophylaxis and early treatment. And of course, we would keep the vaccines on hand in case people wanted them.

But we would also be doing, very rigorous independent, long-term testing on side effects and other kinds of things where we’d be encouraging development of other vaccines, technology and other technology to treat this thing. Right? But we would immediately drop all, but that’s me. That’s me being queen.

Jeffrey Tucker:

That’s also what the last 100 years.

Gigi Foster:

Absolutely, absolutely, right, but in terms of what’s actually reasonable to expect will happen, I just, I don’t see that happening, I see a move towards a slightly less costly regime, which still does have somewhere in it, the idea of COVID is dangerous, and we must protect people from it. And therefore, we must take extra precautions, even though we’re not putting those precautions in place for who knows, let’s say, tuberculosis, HIV, pneumonia, any of the other influenza viruses, blah, blah, blah, blah, long list. We don’t care about those apparently, but we care about COVID and so I just don’t see it being a practical direction as much as I would love that to be the case.

In terms of the natural immunity question. I mean, to be frank, I would rather risk exposure directly to the virus than take one of the current crop of the COVID vaccines based on the data that I’ve seen. And I work very hard to keep my immune system doing well. I had a run this morning and lots of sun here in Australia. And we are in Asia, so as you said, I think it’s likely that actually the COVID lethality here, the cases may rise a lot. And I agree with you, that’s going to happen once we open borders. But the lethality of it may be less than the global average because of the fact that we are in Asia and we will have had sweeps through from other previous COVID type viruses, which probably give a lot of us deep immunity and T cells and whatever. So, I kind of, and with all the sunlight again that we have and the general sportsy culture and everything. Of course, people in Victoria have been seriously damaged by the policies – an act of war.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right. So, what is the political outlook there in Sydney? Because you don’t have a Dan Andrews there in Sydney relative to Melbourne, right?

Gigi Foster:

Honestly, no. Yeah, so Melbourne is the capital city of the State of Victoria and the Premier of the State of Victoria Dan Andrews is the person and the premier across all of the State Premiers in Australia who has gone the hardest and the most draconian in terms of these restrictions on liberties. And we have all manner of political cartoons now. Dana Stan, and let me just, I won’t even, it’s hilarious. I can send you lots of these resistance arts, which is so uplifting.

But we had here in New South Wales, a Premier named Gladys Berejiklian, who for a very long time avoided lockdowns. And I think was really struggling to keep to tow that line for a long time and really tried her best to continue. But then she got embroiled in a corruption scandal thing. And so, she very quickly stepped down. And I think it was not just the corruption story, I think it was probably something else to do with, COVID policy. And we now have a new Premier, who has been a staunch advocate in the past for liberty. He’s very religious. He has six kids, a Catholic, I think. But he’s very much in favor of freedom.

And so, I’m cautiously hopeful about that. I had a conversation with his advisor about a month ago before he became Premier. And I’m sort of, and I got a response, so I’m hopeful that maybe that was a little bit of assistance for him in trying to tow the line and stay the course, basically., The way that Ron DeSantis has done in Florida. There are lots of pressures to stop that foolishness. “What are you trying to do,” right? Because you’re creating an example that will hurt the people who are trying to impose lockdowns and trying to continue them, right? So, of course, they have [crosstalk 00:32:14].

Jeffrey Tucker:

In Australia, you can’t travel to Victoria. You can’t travel to Western Australia. You can’t travel anywhere.

Gigi Foster:

I can’t travel to Queensland. And I mean, I’m thinking of trying to get to Victoria in another a couple of weeks. I’m supposed to be speaking there. And so, we’ll see whether things change by then. But it’s ridiculous. I mean, these domestic lockdowns, on top of the international borders being closed. I mean, if you’re going to close the international borders, that’s bad enough. But then to, on top of that, put everybody into this lockdown state, I mean, it’s madness.

And it just hasn’t been recognized as such. We haven’t had the kind of cost benefit analysis of this policy in Australia that is typical of any kind of policy that has broad reaching effects on the population. And there are reasons for that. I think as soon as you start looking at the idea of doing cost benefit analysis for lockdowns, you realize that they’re a madness, so they can’t be defended.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yeah. And it’s, it’s a problem, too, especially for the travel restrictions because like even in the US, a lot of people who are against a lockdown, school closures, church closures, business closures, favored the border restrictions against China, which were imposed as early as January, I think, January 2020 when Trump. And I’m mortified when I look back at my own writing. It’s like I never wrote and condemned that. I never said anything bad about that.

But then so, March 12th comes and suddenly it’s like, “Okay, from Australia, you can’t come here.” Then it was UK. Then it was Spain. Then just everywhere in Europe. That’s when it just hit me. I thought, “Well, this is appalling.” And even to this day, those are still in place and we’re just making very small steps to have vaccinated only visitors. So, we basically shattered what you and I have taken for granted, and most everybody is taking for granted for the last, the better part of 70 years, which is the freedom to travel here and travel there and do what you want.

Gigi Foster:

Totally agree. And I think back to my childhood. My mother took me around the world. I was 11 years old on something called the Semester at Sea program where we stopped in 10 different countries, 10 different ports. And we were literally on a ship going around the world. And those experiences that I had, during that trip, were formative for me. I mean, I was 11. I was soaking up all these different cultures and different ways of thinking and, just the diversity that you see, kind of experience.

And it saddens me that we have kept now two years’ worth of our young people from having those kinds of experiences. Being able to go on exchange, being able to just, I mean, travel is hard enough. International travel, it’s stressful enough, right? I mean, we know you’re crossing time zones and you have different food. And when are you going to go to the toilet? And do you have enough water? And having to get the itineraries planned out and who’s got the rental car? And what house were you staying at.

All those things are already complicated enough for a poor young person trying to learn and grow and develop and expand their horizons to then put a layer on top of that, that says, “Oh, yeah, and you have all this medical stuff you got to deal with,” is cruel. And it’s going to, I mean, I really feel this is going to create a cost that is not being recognized at the moment, either even by people who are looking at the disruption to education that we’ve inflicted upon our children and thinking about the long cost of that. But this exchange and being able to visit other cultures, it’s hugely important for keeping us a peaceful and vibrant society.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, we’ve lost. I mean, economists for a couple of a hundred years have tried to alert people to think a little bit abstractly about the unseen costs, not just the direct costs, but the unseen costs of the things we do. And that’s what, I’m thinking about drafting an article about it, but we’re not even there. When we think about what we’ve lost in terms of art.

Gigi Foster:

Well, I totally agree and I mean, it’s been amazing, being an economics educator during this period, I teach economics here at the university. And one of the courses I teach is a first year one called Economic Perspectives, where we talk about the big ideas of economics. And of course, opportunity cost is a huge one.

And the story of the Parable of the Broken Window by Frédéric Bastiat, is a great one, which is the little boy comes up and throws a baseball or something or a stone through a window. And first people are like, “Oh, that’s a pity.” But then they say, “Well, at least, it will give work to the glacier. At least, we’ll be able to put him to work and that will help the economy.” And of course, Bastiat’s point is, “Yes, but wouldn’t it have been better to take that money and do something else to improve everybody’s life and livelihood and length of life and all the things we want, instead of having to fix something.”

So, this is the paradox of the GDP measures, for example, as well. The Exxon Valdez spill counts as a positive for GDP, because you have to do all the cleanup, right? Now, that’s just, that’s nonsensical. And of course, you never see what is lost, what is given up on anybody’s spreadsheet. It’s never visible. It’s always in our minds and we always have to just mount an argument about, well, based on what has been seen in the history of humanity and the history of cultures and societies like ours, we would have expected that all of this sacrificed GDP would have been put towards spending on individual preferences. But also roads and schools and hospitals and everything else through our governmental investments.

And those spendings from the private sector and public sector individuals, they directly promote human welfare and that’s what we have sacrificed and it’s so difficult to have that conversation with people who have been wrapped up in this narrative of, “Look at what’s in front of you and respond only to that. Look at the suffering old person on a ventilator with COVID and respond only to that. And if you don’t respond only to that you are a bad person.”

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yep. And but even these invisible costs, they’re huge and they never go away and we’ll never know what they are. But what some people are calling now collateral damage is becoming a little bit overwhelming. I mean, like US hospitals are now full, but not from COVID. But from cancer, accidental injury, which is our euphemism for attempted suicide. All kinds of diseases people have from decayed immune systems and obesity, and drug overdoses, so it’s becoming a little bit overwhelming. I mean, it’s like definitely under reported. But the collateral, the observable collateral damage lockdown is getting a little bit overwhelming, not to mention the policy outcomes from the inflation and the debt crowding out of investment and so on.

Gigi Foster:

Exactly. And I think that that does, I mean, I hate to ever wish suffering on people. But I think that the more evident suffering that is happening now will again, speed our recovery to sort of a normal perspective on what’s important in life. And so, in that sense, it is in service to humanity and to our recovery from this disastrous policy in the States.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Long term. Do you want to put a date on that? What are you thinking in your own mind in terms of like if you are going to imagine a time period in which people have shaken off this group psychology of panic and hysteria and anti-liberalism and we find our way back towards civilized principles of living?

Gigi Foster:

Yeah. And so there are lots of factors obviously and I don’t have a crystal ball, but the kinds of pressures that we are seeing now in very kind of embryonic form, I think will get stronger and they take a while to flow through the system. So, for example, one of the big pressures in favor of recovery is that some areas of the world like Florida or Texas, or Sweden will be back to normal. And to the extent that people will be able to see that, and recognize and be jealous of that, right?

They will put pressure on their own home politicians or they will simply move if they can travel, right? So, if they are able, they’re granted permission to go to some other place, which is having a more joyful and vibrant approach to life and they will do that. And that will eventually deplete the populations in the areas which have clung on to this damaging ideology. But again, that takes time, right? And of course, it takes time for crowds to dissolve. We’ve seen our own history. It takes time, it took time for the prohibition crowd to dissolve, and for the witch hunting crowd to dissolve. I mean, we’re talking about years, we’re not talking about months.

So, my sort of rough guesstimate at the moment in terms of timeframe is it’s going to be between five and 10 years before we get back to real normal. And in over the course of the next five years, I do expect, it will be sort of like when you have a baby, and every year is like a sea change and your ability to do more things, right? Because initially, you can’t even sleep right? And then you go, “Okay, I can sleep a little bit, but now I can’t, I just can’t eat what I would like to. Oh, now I can sleep and eat. Now, we can also do some fun things. Now, I can even do more things.”

So, every year that child’s first five years of life is like a. “Wow, wow, I just discovered that life can be a little more like it was.” And I think that’s what it’ll be like with us. As you think that to the extent that the vaccines are seen to fail more or not be the hero solution that we thought and to the extent that we are able to get stories of early treatment and prophylaxis out there and taken up by good doctors, to the extent that new media channels and new community organizations that become successful and grow legs and such influence. All of those things, they can happen with more or less success. If they’re all really successful, maybe we’re back to normal in three to four years. But if not, then maybe it’s a little longer.

Jeffrey Tucker:

At what point did you realize we’re in for the long haul here because the lockdowns happened in March 2020, I suppose that is true in Australia as well. I remember Australia had congratulatory politicians saying, “We beat COVID.” This is July of 2020. It was hilarious. “We’re the envy of the world.” Yeah, right. But at what point did you, at what point… well, let me ask you this. When did you start your book? At what point did you realize this is going to consume the better part of your career?

Gigi Foster:

So, even in April and early May, I was still hoping that this whole thing would just blow over, really. I was thinking, Well, surely people can’t stay so panicked and so fearful for that many more months. I mean, aren’t they going to realize that life sucks when you focus on one bad thing, and we should appreciate what we have and count your blessings. And take a practical approach and all the stuff that you know happens to you when you sort of recover from a significant fright, right? And you sort of recover your senses, okay, that.

But what I was missing really was the crowd dynamic. I didn’t think that that was going to take hold so powerfully. And so completely in terms of dominating the political narrative, particularly in Australia. So I think it was around probably late June, July, when I started, it started to dawn on me that this was just not going to go away anytime soon. And that I was going to be fighting for the recovery of normalcy here in Australia, despite the fact that everybody was saying it was now normal again. I mean, we couldn’t travel. How is that normal? It’s not normal, right?

And so, I started, sort of, I mean, I had been talking with Paul Frijters during the whole time, because he’s a great friend and colleague of mine. We’ve written previous books together. We’ve written many, many articles together, and we’re basically just intellectual buddies. And so, we had been talking about this. He’d been blogging a lot on COVID issues, even from as far back as March. I’ve been talking on my national radio program about how this was damaging, what we were doing, we should stop. And we spent basically, our entire fourth season of The Economist on ABC Radio National here talking about COVID.

So, Paul and I, just, we were, we were continually putting the voice out there, but we weren’t getting anywhere. And so, we sort of looked at each other and we were like, “I think we need to actually write a book about this.” And that was probably in around September, maybe August, September of 2020. So, it took us, the better part of the year to put the book together. And drawing bits and pieces from different places and packing it in and bringing on Michael Baker as a layperson’s writer.

Because, Paul and I have this previous book right here, which is lovely, but kind of egghead-ish, like somewhat dense, you might say. And so, we recognized that on an issue that was this powerful and this relatable really to the person on the street, COVID policy and why we got it wrong and what we need to do next, we needed somebody to help us make our writing more accessible, and bounce a bit. Make it more lively. And so, and so Michael was perfect for that. And he also is big skeptic of these policies, big nonconformist.

And so just, it seems to work and we put lots of time into it, and I just, it has become obviously something that is still not going away. And as you say, we’ll be consuming the better part of what I’m working on, probably for the next couple of years, at least. And I hope that this period generates, an explosion in research about bad policymaking and the impact of our policies. And that those unseen costs, you were speaking of will be at least estimated by some people, some good economists, and that it will provide fodder for generations of PhD students really to be able to look back on this period.

Jeffrey Tucker:

I’m really proud of the book, especially since Brownstone published it, but also because I think it’s a bit of a monument to the times. So now, we have and this must satisfy you, too that now we have a really coherent documentation of the strange period in which we live.

Gigi Foster:

This was part of what we wanted from the book, absolutely. And putting those initial stories in there from the Jasmines and even from the James, right? Which were taking from people’s posts. That captures what was really happening in these people’s lives and their minds. And I think that’s important. Yeah, so kind of a historical documentary.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yeah. Do you expect you’re going to, are you thinking about a follow-up or I don’t want to… we’re still working with this, but how… let me ask you this, instead of asking that question. How busy do you stay with interviews and book presentations, that sort of thing now?

Gigi Foster:

I’m pretty busy. I’m also teaching two courses, and I’m the Director of Education at the University’s School of Economics. And I’m the Deputy Head of School. So, I have a few things going on. And so, this period has been very, very… I mean, I’m working pretty much nonstop, and not like, we can do that much anyway. I can’t go out to see plays and stuff like that. Hopefully, next year. But it’s been a very, very, very, very busy period. And it does, I am getting a lot of interest in the book.

I would say that it takes a while for the ideas to percolate through, so I’ll have, I’ll send books out. And then, a couple of weeks later, people will say, “Oh, my gosh, this was great. I want some more.” And so, then I have to send more books out. And so just, it has to percolate. The various different worlds that we kind of exposed in the book. It takes a while for people to really get their head around them and recognize, “Oh, yeah. Okay, now, I see this is something I’ve got to push out further. I mean, we need to spread the word about this.” So, I think it will probably keep selling. I’m hoping as a Christmas present, it would be a great choice for Jasmines around the world.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Yeah. Well, the thing that struck me about the book is that I finished it and I thought, obviously, I’m on team Gigi from the beginning here. But I thought, if any the covidophobe or the lockdowner, I read this book, I can’t imagine that he or she would come away not shaken. At least, a little disoriented, and curious about the possibility that they might be wrong about everything. And that’s one of the reasons I really thought it was such a compelling book and based on, do you read the Amazon Reviews?

Gigi Foster:

I have seen them, yeah. I’ve seen most of them anyway. Yeah.

Jeffrey Tucker:

They’re really good.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah. No. Very, very positive. I mean, there’s one which I had to laugh at and I actually would like to extend my thanks to the person who gave us a one star review, saying something like, “Total tripe. Unless you’re an anti-lockdown or anti-vax mandator or believe that COVID is really just like a regular flu, don’t waste your money.” And I thought, “Well, that’s it. Yeah. Because thank you for the advertisement, right?” But yeah, no. They’re very positive reviews and I’ve gotten so many, again, private emails talking about basically the same thing.

Now, on the point of whether reading the book will convince someone who has committed themselves, particularly publicly, to the veracity and the truth and justice of the policies we’ve implemented during this period, I think, one needs to not underestimate the need of people to maintain a positive image of themselves. And so, as much as we might like to in our crusades, to like, “Push this book in their face,” well just look at this, how can you possibly deny, right? That’s not how it works, right?

That’s not how you convince people and the people who we need to read this book also need a face-saving story, so that to themselves and for their children, for their grandchildren, they still have a story of why they’re still a good person. And that is one of the biggest challenges during this period, because this has been such a colossal cock-up in so many ways, right? That if you’ve managed to seem to be associated with it, and to be basically calling the shots or cheering on the people who are calling the shots, where do you hide? What can you possibly use, right?

The only possible fig leaves are things to do with fog of war. We didn’t know at that time even though we did have knowledge, so that’s not true or just “Didn’t know what I was doing?” Or “I was taking orders.” We’ve heard that one before. So, that kind of what we’re asking of someone who was reading this book who has been committed to the pro-lockdown cause is a huge, huge request, which most people will not be able to fulfill. And I fear that if they do, they will be probably living with PTSD, or just some self-hating for most of the rest of their lives. And so this is a recount.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Has this experience had any kind of effect on your opinion of the relationship between good science and public policy, or the capacity of the common person to absorb the realities of that and to their lives and act on it?

Gigi Foster:

Look, it definitely has shaken my faith in the system of peer review that we use in social science and also in hard science in a way that it hadn’t been shaken before. I mean, I recognized that there were issues with favors being traded, and if you know the editor then you can get your article or whatever. But it’s the impact of this crowd psychology on those processes that has been really eye opening for me. We are just as vulnerable in science.

Just like the high IQ people and the low IQ people are equally vulnerable to the crowd dynamic, scientists, too, are human. And we’re just as vulnerable to these kinds of damaging ideologies and just signing up for the crowd. The crowd’s morality and the crowd’s truth, whatever that happens to be at the moment, rather than towing the line on trying to actually query, “Where is truth? What is the what is the right way? What is really going on here?” To the extent that we can figure it out.

Obviously, there’s no objective reality, there’s no objective truth, but we certainly seek it in science. That’s the whole point. Right? I mean, this is one of my favorite documentary film from the BBC in 1973, I think, The Ascent of Man. Jacob Bronowski talks about how science is a testament to what we can know even though we are fallible, right? And so, it is all about trying to pursue that ultimately impossible goal of finding truth. And to the extent that, this period, if has shown me anything, it’s shown me the vulnerability of science as a group to the same kinds of very misguided and damaging destructive dynamics that everybody else is subject to.

So yes, that’s been hard. I don’t know if I’m going to be embraced back into the community of economists in Australia ever, in the same way. I’ve got people who absolutely hate my guts. Won’t go on to debate with me. I’ve had multiple appearances where the host tries to find someone who will be there with me and kind of provide a counterpoint and nobody will do it. They ask multiple people, they won’t do it. People hate me. People see me as literally the devil. So, that’s a real issue going forward and reconciling across those kinds of divides.

In terms of whether people really understand, the dynamics at play in science, I don’t think they do. The person on the street, I think, trusts science, still, more than is warranted. And something like peer review sounds to them like a reasonably pretty good idea, as it often is, in non-COVID times. And you do get some value out of that peer review process, so you don’t want to just throw out the baby with the bathwater. But because of the way that the assignment of referees works in a sudden crisis situation, if you get one paper that’s out there and publishes something that’s misleading, boy, that bad idea can grow long legs and just be around for a long time. And that’s been what’s happened during this period. And we’re going to take a while to recover from that for sure.

Jeffrey Tucker:

But I think last I checked, there’s something like 100,000 published studies on related to COVID and lockdowns, everything associated with it – the medicine, medical aspects, scientific aspects of it. And so, then you have a problem, which ones you’re going look at, because it’s just been this flood. I mean, you saw that link on Brownstone, we had 91 studies in natural immunity. Okay, well, how many do we need before people start paying attention, 910?

Gigi Foster:

Look, I mean, the problem is, right there. Yeah, I know. During this period, there’s been no scarcity of facts and evidence. The scarce thing has been common sense. And really that it is not something that you need to have a PhD to work out, which is why we’ve seen the most sense making, coming from people like the truckies or the repair people, or there’s the blue collar workers because they can sniff a rat. These people have street smarts. And really, the PhD training only gives you the tools to be able to better rationalize, in some florid ways, some really dumb ballsy, right?

And so, yeah, I think knowing that there are going to be studies coming out saying this, saying that, saying the thing, it’s useful to know that that will happen sometimes for political reasons. Not every peer reviewed study is gold. Not every one is. And even if you don’t really know the ins and outs and the technical details and the mathematics that you need in order to decipher a particular study, you can use your nose. You can use your street smarts and just try to get a sense check what you’re reading as a lay person. And I think it’s the responsibility of those of us who can penetrate those technical articles to call them out on their unethical, statements and assertions and incorrect inferences, because if we don’t, who will?

Jeffrey Tucker:

That’s right. And it takes so much time and we’ve been doing it for a year and a half. We’re going to be at this two years more. We’re going to be five years in this. Gigi, thank you so much for visiting with me tonight and for writing this amazing book that I’m certain will stand the test of time and so, you’ve been glorious. So, thank you so much.

Gigi Foster:

Thank you so much. Thank you, Jeffrey. Thank you for all your support and your unending energy. And trying to crusade for what is right and true.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Thank you, Gigi. Good night.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.