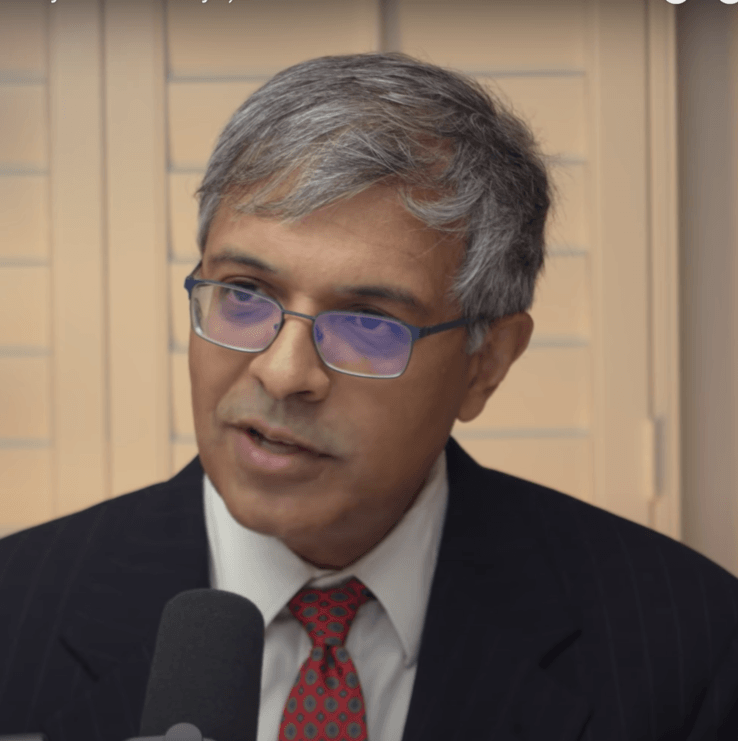

In this interview, Lord Sumption and I discuss the legal, ethical, and political implications of COVID-19 policy responses. The interview from July 2021 was arranged and produced by Collateral Global, where the audio version is posted.

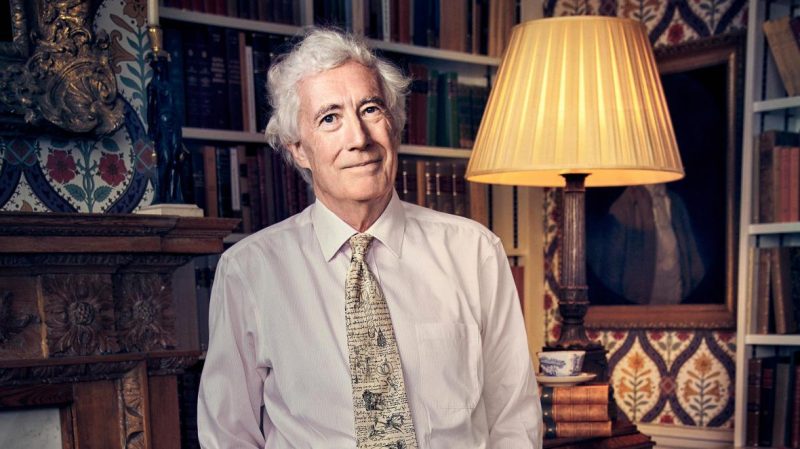

British author, historian, and retired Supreme Court Judge, Lord Sumption, has been vocal throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, questioning the wisdom, necessity, and legality of the British government’s use of the 1984 Public Health Act to implement extraordinary lockdown measures.

In this in-depth conversation, I sat down with Lord Sumption to explore pressing ethical and legal questions raised by the COVID-19 policy response, in addition to examining both the historical context and potential ramifications for the future.

Jay Bhattacharya: Lord Sumption, thank you for joining me and thank you for giving up the time and the opportunity to me to speak with you about your views about the pandemic, about your experience as a judge and how those experiences have shaped your views about the future of democracy in the UK and the US. I want to start talking a little bit about a book of yours that I read in preparation for this conversation on the lockdown and, in particular, on the aim of the book, which it seems to me was written in large part before the pandemic. And it aims to provide your views about the norms on which democracy is based. And in my reading of the book, especially the last chapter, which I think you wrote during and after the lockdowns were instituted, that you didn’t have a particularly rosy view about the institutions and the strength of the institutions on which democracy was based even before the pandemic. My question to you is, were you surprised nevertheless by the lockdowns and essentially what they represent, which is the jettisoning of democratic norms, including the protection of property rights, the right to education, the treatment of the poor and so on? Is my impression correct, or was there a continuity before the abuse and after the abuse, after the lockdown started?

Lord Sumption: There’s a continuity in some respects, but not in others. I was surprised by the lockdown when it was introduced in the United Kingdom. And I’ll say a bit more about that in a moment. But it’s always been my view that democracy is a very vulnerable, a very fragile system. It has existed for a relatively short time. Democracy in the West essentially dates from the late 18th century. So we have had slightly more than 200 years of it. In the full perspective of human history, that is a very short time. The Greeks warned us that democracy was essentially self-destructive because it led naturally to faith in demagogues who absorbed power with popular support in their own interest. Now, the interesting thing is, why has that not – for most of the two centuries or so that democracies have existed – why has that not happened? The reason it hasn’t happened is that the survival of democracy depends on a very complex cultural phenomenon. It depends on assumptions that the system has got to be made to work. And those assumptions have to be shared between those who may have radically opposing views about what the system ought to do. Their views are subject to that overriding feeling that the system itself has got to be workable potentially in the interests of both sides of the argument. Now, that’s quite a sophisticated position, and it is dependence on the existence of a shared political culture, shared between both sides of the major political debates and shared between professional politicians on the one hand and the citizens who vote for them on the other. Now, it takes a long time for this kind of shared culture to be created. But it doesn’t take very long to destroy it. And once you have destroyed it, once you have broken the basic conventions on which the survival of democracy depends, you fatally weaken them. And the more radically you break them, the more completely you undermine and potentially destroy them. Our institutions depend only partly on written constitutions or laws on judicial decisions. The world is full of countries where democracies have been subverted entirely legally by governments. You only have to look at what has happened in the United States in the last four years to see how a government of laws can be subverted by a government of men.

Jay Bhattacharya: So you wrote in a fascinating essay about the Magna Carta that,

“We are all revolutionaries now controlling our own fate. So when we commemorate the Magna Carta, for us, the first question that we should ask ourselves is this: do we really need the force of myth to sustain our belief in democracy? Do we need to derive our beliefs, a democracy, and the rule of law from a group of muscular conservative millionaires from the north of England who thought in French, knew no Latin, no English and died more than three-quarters of a millennium ago? I’d rather hope not”.

So is there a possibility of an alternate myth? I mean, do we actually even need a myth? How do you replace what you’ve outlined here as a fundamentally pessimistic vision about the possibility of a democracy so that survives? Is there given, what we’ve seen about lockdown where basic fundamental rights been violated that I think we all thought we essentially had secured, is there any hope of replacing that myth with some other myth or maybe some other legal structure? Or is it simply that we’re in for a dark age?

Lord Sumption: Well, I’m afraid I think we are in for a dark age. The point about myth is that you need myth if you place your golden age in the past. Almost all human societies have a vision of a golden age. For centuries, perhaps until the end of the Middle Ages, people placed their golden age in the past, and they embroidered the past. They developed a myth about what the past had been like, a myth about what they were trying to recover for their own day. For three or four centuries now, western societies in particular have placed their golden age in the future. It’s something that they aspire to. Now, to create something for centuries ahead, myth is just irrelevant. And so, I don’t think we need myth. What we need is a culture of cooperation, a culture which is dedicated to something which laws are not strong enough to create in themselves. What has happened over the pandemic? Governments need to have emergency laws because there are catastrophes, which can only be contained by the exercise of such laws. But their existence and their workability depends on a culture of restraint about the circumstances in which they’re going to be used and the extent to which they’re going to be used.

What we have seen at the time of the pandemic is a very remarkable thing because interaction between human beings is not an optional extra. It is the basic foundation of human society. It is the basis of our emotional lives, of our cultural existence, of every social aspect of our lives and of the whole model under which we cooperate to produce collectively benefits for ourselves. All of this depends on the interaction between other human beings. Now, it seems to me, therefore, that a regime which seeks to make it a criminal offense to associate with other human beings together with other human beings is a profoundly destructive – I would go further and say a wicked – thing to do. I do not suggest that the people who do these things are wicked. They, in most cases, are animated by feelings of goodwill and a genuine desire to help people. But although they are not wicked, although their intentions are sound in most cases, what they are actually doing is a very seriously damaging thing for any human society. Now, I don’t believe that liberty is an absolute value. I think that there are circumstances. It’s why I believe that these parts have got to exist. There are clearly circumstances where that exercise is justified. If we were talking about Ebola with an infection fatality rate of 50%, or a sudden escape from a laboratory producing a mass outbreak of smallpox, infection fatality rates say 30%, then I could see the point. But we’re not talking about anything like that. What we are talking about is a pandemic, which is well within the range of disasters that human societies have learned to cope with over many, many centuries. There are plenty of statistical indications of that. I mean, you can choose a number of them, but to me, the most telling fact is that in the United Kingdom, the average age at which people die with COVID-19 is 82.4, which is about a year ahead of the average age at which they die of anything. In the United States, I believe that the comparison is equally close, somewhere around 78. And this has been the pattern in most countries with the demographic age balance that most Western societies have.

Jay Bhattacharya: There’s a thousand-fold difference in the risk faced by the old relative to the young from getting infected.

Lord Sumption: It’s a highly selective epidemic with which we are trying to deal by wholly unselective methods.

Jay Bhattacharya: Exactly. I mean, of course, I argue for focus protection as the right way to deal with the epidemic. But let me return to that afterwards because I want to push you just a little bit further on your thoughts about democracy. It’s striking when you talk about the fundamental needs of humans interacting with one another. And of course, the inversion of that has been the fundamental that somehow during the epidemic, the fundamental human need to interact is a bad thing, a wrong thing, a horrible thing. In a way, it’s become a moral good not to interact with another. It comes to mind, and I think I read this in the book by CS Lewis, where he talks about tyranny exercised for the good of its victims, where the idea is that the people engaging in the tyranny. Well, they do it because they think they’re doing it for your own good by force. And here, with lockdowns, that’s what we’re seeing. We’re seeing that public health is forcing you to stay apart from your grandchildren, from your kids and whatnot. And they think they’re acting virtuously, and there’s no limit to what they’re willing to do because, well, they’re doing it with their own conscious telling them that they’re doing the right thing. I mean, how do you turn that around? I mean, I agree with you; the fundamental human need requires us to interact with one another. But how do you turn it around; this idea that’s taken hold of the lockdown that these interactions are a bad thing?

Lord Sumption: All despotisms – or almost all despotisms – believe that it is for the good of the people that they are being deprived of their freedom of action. Classically, Marxist theory says people are not capable of deciding what they want because their decisions are closely dependent on social constructs which they did not themselves create and which it’s necessary, therefore, for more enlightened people to dismantle before they can really be free. This is the myth of despotisms of both right and left. And it is a profoundly destructive myth, the effects of which we have seen in Europe over the 20th century. And it’s not a world in which any sane person would want to return to. The essential problem about the lockdown and similar methods of social distancing is that they are designed to prevent us from carrying out our own risk assessments. Now that is, I think, a serious problem in any circumstances for mainly two reasons. The first is we may not actually want to be completely safe.

There’s a trade-off between safety and the actual content of our lives. We may be quite willing to decide that we would rather take the risk of living a little less long in order to have a richer life while we are alive. At an extreme, I can take the example of a friend of mine who is 93. She is an intensely intellectually vigorous woman. She has led an active intellectual life as a journalist throughout her adult life. She lives for society, for having people to her flat for dinner, for going out. And she says, I think understandably, I feel as if I am being buried alive. What is more, she says, I may have three or four years left, and the government has confiscated a quarter of those. I feel strongly about that. Now, she is entitled, morally entitled to my mind, to say, “I don’t want to have this standard of safety imposed upon me by the government. I have my own standards, and my autonomy as a human being entitles me to apply those standards to myself and to the people around me”. That, I think, is one objection. The other objection, of course, is that it is unbelievably inefficient, especially with a pandemic of this kind, because it is a highly selective pandemic. It overwhelmingly concentrates its effect on the old and on people with a number of identifiable clinical vulnerabilities. Yet, although the pandemic is selective, the measures taken to counter it are completely indiscriminate, so that we impose on everybody an obligation to do nothing. At its extreme in the United Kingdom. We are spending about twice as much every month on paying people not to work as we spend on the health system. Now, that seems to me to be a perfectly absurd state of affairs. We could be spending money on training up additional nurses on additional hospital places. We could be doing things that actually had some impact on the treatment of the disease. Instead of which, what we have done is interfere with the one mechanism which people are most in need of in times of crisis. Namely, the ability to associate with and support each other.

Jay Bhattacharya: I mean, it’s striking to me that the UK has had such a success in vaccinating the older population, who are really at the highest risk of severe disease. And, in a sense, because of that success, the UK is no longer in severe danger from the disease because the population that was once at the highest risk is no longer at such a high risk because such a large fraction of the older population is vaccinated. Yet we haven’t seen the UK declare victory to say, “Well, we’ve conquered the worst parts of this disease”. The lockdown is continuing in the UK despite that success. And for the young, I think you agree, and I certainly agree, the harms of the lockdown are so much worse than the disease. And that’s true for the vast majority of people. And there’s two puzzles in my mind. One is: Why are the young so much still in support for the lockdown? It strikes me that the young have been harmed by the lockdown very substantially, both the very young, because of loss of schooling, disruptions in their normal social life and development. And also for the young adults who’ve had their jobs disrupted and especially the ones that aren’t at the top of society who can’t replace their work with Zoom. It seems to me like the young are harmed in ways – so many ways – by the lockdown. And so it’s a puzzle to me why there’s so much support.

Lord Sumption: Well, I agree with your diagnosis entirely. I think that – I don’t profess to understand it entirely – but I think that I can offer at least a partial explanation. The first is I think that the young now lack a historical perspective which would enable them to understand better the dilemmas of human societies and the experience of the past, which is often very instructive. But the second factor that is, I think, important is the politicization of this issue. It shouldn’t have been politicized, but both in Britain and in the United States, the opposition to lockdowns has been associated with the right and the support of lockdowns with the left. I think that this is a quite extraordinary dichotomy because the issues raised by the pandemic and the measures taken against it are absolutely nothing to do with the traditional values which have animated debate on the right and on the left of our political spectrum. Nothing whatever. And therefore, I find it very surprising that this has happened, which it undoubtedly has. And one of its consequences, the young, on the whole, tending to be more left-wing than their parents is an instinctive acceptance of social control as the answer to any major problem. I think there is also among the young, a natural and, I think, unjustified optimism about what human societies can achieve. I think that has led them to believe that there is potentially nothing that human societies can’t do if they have enough goodwill and throw enough money at it. Actually, what we are learning it the moment, is that there are many things which human societies have never been able to do and can’t do now, and that is entirely to immunize themselves against disease. Things like vaccine achieve a high degree of protection, but nobody, I think, pretends that they eliminate disease entirely. The World Health Organization says that only two epidemic diseases have ever been totally eliminated. The most best-known example is smallpox and that took nearly 300 years after the development of the first smallpox vaccines. So we have – and this, again, goes back to my point about the lack of historical perspective – we have an excessive degree of optimism about what humans can achieve and the problem is that when that inevitably happens, these expectations and hopes are disappointed, we do not say, “Well, we were too optimistic to begin with”. We say, “The politicians, the institutions have let us down”. That is the number one reason why democracy has lost its hold over people, especially in the younger generation. This is a phenomenon that has been attested by polling evidence throughout the West. The Pew research polls on world opinion over the last 25 years, the Handsard Society’s annual survey of political engagement in the United Kingdom all point to the same conclusion, which is that people are turning their backs on democracy, especially among the younger generation and especially in the oldest democracies where the initial idealism is no longer enough to sustain the idea. That is a very serious state of affairs.

Jay Bhattacharya: In the 1960s, we had a rebellion of the youths against the Vietnam War, against conscription of the Vietnam War in particular. And this led to the idea that if you’re young, well, you shouldn’t trust anyone over 30. The idea is not just the lack of trust of people under 30. I’m over 30 myself, which that would hurt me if young people were to say that. But in some sense we old folks…Well, there’s a well-deserved lack of trust that young people might have in us for imposing the harms of the lockdown on them. But the reaction of the youth hasn’t been to try to reform the structures – that, in some sense, is what you’re saying is – the reaction to young people is to reject the structures altogether that might have allowed them to push back against the hands of lockdown they faced. And I don’t know how to address that, but it’s a real problem.

Lord Sumption: I think it is a real problem, but I think that the key to it is disappointed expectations. Looking back historically, as I am, afraid, almost inevitably tend to do, the best exemplar is probably the United States. The United States has had a charmed existence, except during two relatively brief periods. One during and immediately after the Civil Wars of the 19th century, and the other during the slump of the 1930s. The United States has had a continued upward economic trajectory. The same is true in a slightly more accident-prone way of Europe. The disappointments of expectations about the future is the main element in the rejection of democracy pretty well wherever it has happened. And the principal historic example of this, certainly in Europe, has been the mood in the immediate aftermath of the first World War. Disappointed expectations, disappointed hopes of improvement in the lot of mankind, were I think the main reason why between the wars so many European countries turned to cruel and insufferable despotism as the solution to their problems. And what we are seeing now is a less dramatic version of the same problem.

Jay Bhattacharya: Less dramatic for now, hopefully…

Lord Sumption: Less dramatic for now, I hope less dramatic forever. But as I said, I’m not optimistic.

Jay Bhattacharya: I want to return to the lockdowns, and to a theme I’ve heard you say in other public appearances about fear caused by the lockdowns and essentially a policy of fear of the disease. So one of the things that struck me during the epidemic is how the public health agencies implementing the lockdown have used this fear. The fear is not just an accidental by-product of the facts of the epidemic. The facts of the epidemic, as you say, and the disease, as you say, are in line with many other diseases we’ve faced in terms of the harm. But in fact, there was a policy decision by governments to create fear, essentially to induce compliance with lockdowns. I read an article in the Telegraph and the main point of it was that in the UK, there’s a scientist on a committee that encouraged the use of fear to control behaviour in the pandemic. He admitted that its work was unethical and totalitarian, and this was the committee. This is the scientific Pandemic Influenza Group of Behaviour, which is a subgroup of SAGE. They expressed regret about the tactics and, in particular, about the use of psychology as a way to control the population. Is it reasonable for governments to cause fear and panic in service of a good cause, you know, disease control? Or is this an unethical totalitarian action that should not have been done?

Lord Sumption: I think that the first duty of any government in dealing with any issue whatever is objectivity and truth. There are no circumstances in which I would accept it is legitimate for governments to lie. And in the category of lies, I would include distortions of the truth and exaggerations. I think there are circumstances mainly concerned with defence in which it is legitimate for governments not to disclose things. But the active falsification of facts is never forgivable. In this country, there was a notorious memorandum produced by the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, SAGE, immediately before the lockdown on the 22nd of March, in which basically what this committee of SAGE said was, “We’ve got a problem here, which is that this is an epidemic which is selective. A lot of people will feel that there’s no reason for them to be alarmed because they are young and have good underlying health. We’ve got to deal with this. So what we need is a hard-hitting emotional campaign” – that’s actually the words that they used, “…to persuade everybody that they’re at risk”.

Now that to my mind is a lie. It’s a program for the deliberate distortion of people’s judgments by pretending that the epidemic is other than it is. Before the lockdown, the chief medical officer in the United Kingdom gave a number of very straightforward, perfectly balanced statements about what the risks of the epidemic were, who was primarily at risk and what the symptoms were in different categories and made the point that, in fact, there was no need for alarm except amongst certain people whose interests clearly had to be carefully protected. All of that stopped with the lockdown. Before the lockdown, SAGE had advised consistently along two particular lines. First of all, they said, you’ve got to trust people and carry them with you. So no coercion. Secondly, they said that one should try to ensure that life is as normal as possible, except for people who particularly need protection. That should’ve been the basis of planning for this pandemic, which had been in place since 2011 in this country.

It was also the basis initially of the World Health Organization’s advice. And it was the basis on which highly respected health institutes, like the Robert Kosher Institute in Germany, had advised their governments. Now, all of that went out the window in the course of March 2020. Nobody has ever identified any specifically scientific reason why this advice, which was carefully considered, should suddenly have been regarded as inappropriate. Indeed they’ve shied away from the subject altogether. It was a very odd state of affairs. The reasons for the change were not scientific; they were essentially political. People who have a high degree of confidence in government as the safeguards against every misfortune said, “Look what they are doing in China, in Italy, in Spain, in France. The government is taking action there. This is very manly and admirable of them. Why are we not doing the same?”

People who see abrasive action being taken elsewhere tend to say, “Well, look, action is always better than inaction. Why aren’t we getting on with it?” This is essentially a political argument. It’s not a scientific one, but it was decisive. In this country, Professor Neil Ferguson, responsible for some of the most doom-laden statistical prophecies which have been issued at any time in any country about the pandemic – most of which have been held…have been found to be exaggerated – gave a most revealing interview to a national newspaper in which he said, “Well, we never really thought about lockdowns because we never imagined that it was possible. We thought this was unthinkable and then China did it and then Italy did it. And we realized we could get away with it.” That’s almost a quote. Now, actually the reasons why we did not behave like China before March 2020 were not just pragmatic reasons. It wasn’t that we thought it wouldn’t work. The reasons were essentially moral. These were fundamentally contrary to the whole ethos on which our societies are built. There is absolutely no recognition in people who speak like Professor Ferguson spoke in that interview – no recognition – of the fact that we have moral reasons for not behaving in their despotic fashion; for not wishing to be like China even if it works. Well, now there are disputes about whether it does work. But even if it works, there are moral limits, and they have been transgressed in a really big way in the course of this crisis. The result has been that what began as a public health crisis is still a public health crisis, but it’s an economic crisis, an educational crisis, a moral crisis, and a social crisis on top of that. The last four aspects of this crisis, which are much the worst aspects, are entirely manmade.

Jay Bhattacharya: I mean, striking thing to me, as you say, is that how do we follow different policy? The fear that we created is not in line with the facts. For the oldest people are not equally vulnerable to disease as younger people. For the youngest people, the…For the oldest people, in a sense, they underestimated the harm of the disease relative to what the truth was. And because they thought they were ever was equally at risk, they engaged in behaviour that, from a public health point of view, was harmful because the older people exposed themselves to more risks than they probably ought to have given the facts. And the younger people, because they fear the disease more than they ought to have, they didn’t interact with another and harm themselves as a result. And it’s striking that the public health establishment, which pushed this line of ‘equal harm, equal risk’, they closed themselves around in a way that…away from other all sorts of policies that could have addressed the true risk faced by the old.

For instance, a focussed protection policy would have done that while also help the young understand the risks that they face as well – much lower from COVID, much more from lockdown. And yet, instead of adopting these alternative policies like Focused Protection, public health officials sort of engaged in fierce backlash against it – de-platforming, slander. Essentially they shut the debate down. So in the context of liberal democracy like the UK and the US, I find it extremely striking and frustrating that when we most needed this debate, the people who’d want to engage in it were pushed aside. And I’m sure you personally faced a fair amount of backlash for speaking up. I certainly have. Can you give me your thoughts about this? What do you think is the basis for the setting aside of free expression, free debate? Why did you personally speak up? And actually, if I can get to one other thing that maybe I can have you address, is what effect do you think this pushback on you regarding your decision to speak up, what effect do you think it might’ve had on people who are not in the same position that you and I are in? Where we have jobs that are protected or positions that are protected against retaliation.

Lord Sumption: Well, as far as the health establishment and ministers are concerned, the main problem has been that they were pushed into this in a moment of blind panic in March of last year. It is completely impossible for people who have done that then to change their mind because they would have to turn round and say to their people, “Okay, it was a mistake. We inflicted weeks of utter misery and economic destruction upon you for nothing.” Now, I know of only one government that has been brave enough to say that. It’s the government of Norway, which at one stage admitted that the catastrophic collateral consequences of lockdown were such that if there were further waves, they would not repeat the exercise. So, that, I think is the relatively straightforward explanation among the broad class of decision-makers. Why have others not spoken out? To some extent, I think it is very largely due to the fear that by speaking out they will lose status and possibly lose jobs. I have not been the subject of sustained abuse as many people like Sunetra Gupta, for example, have been in their profession. I don’t know why that is, but I suspect that it has a lot to do with general respect for even the retired judiciary in this country. I’m in a very fortunate position. I’m completely retired. I have a secure pension. I’m not beholden to anybody. There is nothing bad that anybody can do to me – nothing that I feel any reason to be concerned about.

Now, that is a relatively unusual position. I get a lot of messages from members of the public – some of whom are in influential positions – which say, “We’re grateful to you for speaking out. We don’t dare to do it because it would simply ruin our careers or our influence” Now, some of the people who have sent me these messages are members of Parliament. Some are quite senior consultants in hospitals. Quite a few are prominent academics. Now, if these are the people who feel that they cannot express a view contrary to the prevailing norm, then we really are in a very serious position. Now, the problem is that with modern methods of communication, the consensus among what you can call the establishment is amplified by the media and, particularly, the social media. The YouTube and Facebook internal rules about what they will regard as unacceptable opinions are astonishingly craven. The YouTube rules basically say, “We are not prepared to allow the expression of opinions that are contrary to the official health policies of governments” Now, that’s what their rules say. In fact, they haven’t carried that to the ultimate degree. They have allowed a fair amount of dissent. And personally, I have never been censored although I have been a prominent critic of these policies pretty well from the outset of their implementation. But many other people; journalists, distinguished medics like Sunetra Gupta and Karol Sikora have found themselves censored on YouTube and on other social media for exactly this reason. Now, in a world where their views are being amplified, I think this is a very serious thing.

Jay Bhattacharya: Yes, I was on a panel with the governor of Florida discussing lockdown policy. It was publicly filmed, put on YouTube, and YouTube censored that conversation with the governor of Florida, where the governor is attempting to communicate with the public about the basis of his reasoning to not adopt a lockdown. And I found it striking. I mean, it’s like there’s almost two norms here. There’s this norm in public health where needs to be unanimity in public health messaging. And YouTube is attempting to enforce that norm rather than the norm of free democratic and scientific debate. It strikes me that this is, as you say, a political issue where the normal free democratic debate that ought to be the real norm that rules, and yet it hasn’t. It has not ruled, and much of the conversation has been shut down. It’s made the lives of many people who’d want to be able to say something very difficult, I think.

Lord Sumption: Well, despotic measures by governments inevitably invites forms of censorship and enforced conventional opinion. The extreme example of this is Victor Orban in Hungary, who said at an earlier stage that the pandemic required you to have complete control over what was said about the pandemic in the press. And he duly had laws passed which confirmed those powers upon him. Well, in Britain and the United States, we have not done anything quite as crude as that, but I think that there is a tendency for despotic measures and either censorship or pressure to self-censor to become part of the ordinary way of life. I think you also have to remember that the social media are, at the moment, under distinct pressure from governments on a wider front. There are strong movements – certainly in Europe, I think probably less than the United States – to make the social media responsible as publishers and therefore liable for defamation for all the things that may be said by some of the more cranky people who contribute to messages on the social media, and governments are trying to reign them in. In some cases, there is an element of political control freakery about this, notably in some places like, well, Russia is an obvious example, but also in parts of Eastern Europe. Now, the social media have responded to this by trying not to offend governments too much. In Britain, there have been a number of initiatives – none of which have so far got anywhere but many of which have had strong political support – to control what the media, what the social media, broadcasts. And I think that there’s been a strong element in outfits like YouTube, Facebook not to upset the government on an issue like the pandemic. They wanted to be good boys.

Jay Bhattacharya: I’ll ask you about judges. And, in particular, it’s been a revelation to me. Unlike you, prior to the pandemic, I had almost no knowledge or interaction with the judiciary or courts with judges at all. But during this pandemic, I’ve served as an expert witness on a number of cases in the US and Canada challenging various aspects of lockdown, including the right of churches to open, attend Bible studies in private homes, for school districts to have school in-person to meet their obligations, provide education to children, political candidates to hold meetings, public meetings prior to an election – all of this has been stopped by lockdown policies in the United States. And I’d say the experiences have been frustrating to me. In 2020, nearly every case I participated in, we lost. We ended up losing.

Lord Sumption: Now, there’s spectacular exception to that.

Jay Bhattacharya: And a few of those appealed, and we’ve won. In particular, I’ve gone to the Supreme Court, at least the cases I’ve gone to have gone to Supreme Court, several of them. And the US, of course, had to rule on it. But it’s striking to me that the US Supreme Court had to rule on something that’s so fundamentally obviously within the norms of what judges and the judicial system protect, which is the basic right of political candidates to give speeches during election or for worshipers to worship freely for their religious observance. It seems like such a fundamental right. So I have a few questions about that. So one: should we expect courts to uphold these kinds of basic liberties in the middle of pandemic? Or is it reasonable that they give leeway to governments to control this kind of behavior? So, is it okay to suspend free speech, free assembly, free worship rights, and so on during a pandemic? Was it something we should’ve expected judges to push back on?

Lord Sumption: Well, I think that depends on the legal framework of each country, some of which have more authoritarian traditions and confer wider powers on government than others. If you take the United States, I think in some ways the most interesting decision is the Supreme Court’s decision on the closure of churches in New York. Now the constitution says that Congress and the states may not pass laws interfering with the free exercise of religion. Now, whatever you may think about the current political attitudes of present members of the US Supreme Court, which I know is a controversial issue, I really don’t understand how this can be controversial. How can it possibly be said that closing churches is not an interference with the free exercise of religion? I am astonished that there were three dissenters in that case. All of them people who are essentially on the more left side of the Supreme Court, but they are people who, as lawyers and as thinkers, I personally enormously admire. I think people like Stephen Breyer, completely admirable in that instance. I do not understand how it is possible to defend the closure of churches in the face of an absolute constitutional rule like that. I do not understand how it is possible to say that it isn’t absolute. However, that is what happened.

In this country, we don’t have a written constitution. There are no absolute rules. We have statutes, but a statute can do anything. So the juridical framework is a lot less favourable to challenges. However, there was a major case in the United Kingdom in which the question was whether the Public Health Acts authorize this kind of thing. Now, I have no doubts that the British government does have power to lock people down, but not under the Public Health Act. It has power under another statute which authorizes the government to take emergency action in the face of certain categories of emergency – including public health emergencies – provided that they submit to a very tight regime of parliamentary supervision. Under the Public Health Act, there isn’t a tight regime of parliamentary supervision. So naturally, our government preferred to go under that Act. I think that was completely wrong because the Public Health Act is concerned with the controlling the movements of infectious people and the use of contaminated premises. It is not concerned with healthy people. It is concerned with conferring on ministers that some of the powers which magistrates have to close contaminated premises and isolate infectious people. The Court of Appeals and the Court of First Instance both essentially said, “Well, this is a very serious situation. The government must have power to do this. The legislator when he passed these laws – in 2008 in this particular case – must’ve had in mind that more abrasive measures than that would be available for a pandemic like this”.

Now, why should they have had this in mind? Nobody had it in mind until a few days before the 26th of March, 2020. It had never happened in history before in any country. So why this should have been regarded as part of the toolkit when, as professor Ferguson rightly said in his notorious interview, it was completely unthinkable, I simply cannot imagine. And I think that that is a tendency in judges, certainly in this country, not to want to rock the boat in what is regarded as a national emergency. A tremendous rouge during the second World War about the internment of aliens or people of alien origin. The United States locked up all ethnic Japanese at the beginning of the war in early 1942. We locked up everybody who we thought had opinions that were inconsistent with the war aims as well as many, many aliens. In both countries, this was challenged right up to the highest court. And in both countries, it was very doubtful whether the power to do these things actually existed. In Britain, there was a notorious case called Liversidge & Anderson in which the Home Secretary was challenged for locking someone up when there were no grounds for doing so. And he argued, “Well, in this kind of situation, I must be the judge of whether I’ve got grounds for doing so. And if I think I’ve got grounds, then I have”. That was an argument which, extraordinarily, was accepted. And an argument, which was not actually very different, also succeeded in the case of the internment of ethnic Japanese in California, in the United States. Now, these are widely regarded in both your country and mine as the lowest point which the judiciary exercising public law powers ever reached. We should be ashamed of it. And yet this same resort to expediency – it’s expedience that the power should exist, therefore it does – has been seen in the course of this pandemic. I think it is a regrettable but powerful judicial attitude that when faced with a crisis, we must all pull together, including the judiciary, and maybe the rule of law doesn’t matter quite so much or has a special meaning in such a situation. I don’t accept that for a moment, but unfortunately, there are people who do, and some of them are judges.

Jay Bhattacharya: I think it’s striking you use that analogy because I agree with you that in many ways, when you look back on those kinds of decisions in the US, like the Korematsu decision, we look back with shame. And I think about what motivates a judge to make a decision like that. It must be fear. And I think you can think about fear in two ways. One is, of course, the fear we all might face from a disease itself. But the second, probably more important, is the fear that the judges face that if they rule against lockdown, maybe they’ll be blamed for valuing the law over and above human life, right? And I think that must play some role in how judges think.

Lord Sumption: I think it’s a large part of it, yes. Judges claim to be fearless, but they want to be loved. And I’m afraid our judges are no exception.

Jay Bhattacharya: Okay. So let me thank you for spending so much time with me. I just want to take one more opportunity to talk about the obligations that we have as a society to the poor, the sick, and the vulnerable. And I’ll give you one chance, and we’ll end our conversation after that. So, it’s been striking to me – and I do health policy for living – it’s been striking to see the health policy ignore every other aspect of health other than infection control, and then only focus on one infection at that. I’ve been struck by the abandonment of the developed world of its sense of obligation to poor nations. And we can see that most starkly in the prioritization of vaccines, for instance, for the young and healthy in the US and UK. As we’ve said, the young face vanishingly small risks from COVID, especially relative to the elderly, including elderly in poor countries who still face a very substantial risk of harm from COVID. I assume politicians followed both of these policies because it’s popular with a sufficiently large fraction of the population to make it worthwhile to do so. Yet these populations, in normal time, strongly support investments in population health, both home and abroad. Is there a sense of what you can say to the expressed opinions of the people that they don’t actually reflect their true values and commitments? I mean, they’re acting out. Well, in economics there’s this idea we have of a hot brain and a cold brain. And sometimes a cold brain is our true self, but our hot brain sometimes takes over. And in the midst of fear or whatnot, we do crazy things. We act out of character, with our hot brain taking over the actions that normally our cool brain would deal with, in a sense. I guess my question is, how do you call people back to the better angels of their nature, as a famous American president once said?

Lord Sumption: I don’t think that the problem is the split personality. I think that people are altruistic up to the point where that altruism directly harms them or they think it does. People are in favor of, for example, aid to the third world because the adverse impact on them in taxes is pretty minor, not separately identified, not terribly noticeable. Vaccines are different because, at a time when there isn’t enough vaccine to go around – even in advanced countries it’s a situation we’re only just getting out of now – people will say the first duty of the governments which have funded at huge expense these vaccine programs is to the people who are paying for it. And every consignment of vaccines that goes into the arms of people in Africa is not going into the arms of people here. What you’ve got there is a direct competition between the interests of the third world and the interests of the West of a kind which does not normally arise. So I think that people are actually consistent about this. I think that altruism has always had its limits, and this is the sort of occasion when those limits become visible.

Jay Bhattacharya: Well, thank you so much for spending time with me. I mean, unfortunately, I think we have to leave it at this. We haven’t really given our listeners a ton of hope going forward, but I think it does help to discuss these issues forthrightly. And my hope anyways is that by doing so we can start to make better decisions than we have made. Lord Sumption, thank you so much. Appreciate the time.

Lord Sumption: Thank You

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.