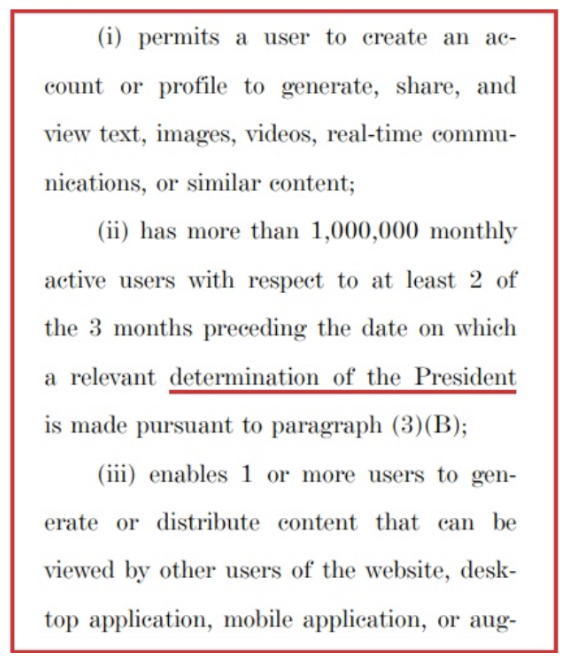

In the news this week, there is a lot of controversy over the US House of Representatives voting on Bill HR7521 which gives the Executive Branch of government the power to control and/or censor the content on websites and apps that are considered to be foreign-owned.

The public debate centers around the Chinese-owned social media platform TikTok, which collects massive amounts of data and has remarkable influence over American citizens, especially kids. Proponents of the bill argue that TikTok is a danger to our sovereignty as a country because of its foreign ownership.

On the other hand, critics of the legislation assert that the bill enables the largest control grab since the Patriot Act, empowering the president with unilateral authority to determine which businesses are permitted to operate in the US.

As the TikTok question is taken up, it is timely for a review of the origins of our major tech platforms and an examination of their troubling interconnectedness with the federal government.

Over the last few centuries it has been widely understood that power was generally acquired by leveraging rich natural resources, money, and/or a strong military. As globalization has evolved and humans across the planet have become interconnected with access to an unprecedented amount of information at their fingertips, one can make a case that the control of this information has become the most important weapon in the power arsenal. Whoever controls the narrative, sways public opinion, guides individual and group behaviors, and paves the way for powerful institutions and individuals alike.

As the TikTok debate highlights, it’s evident in the Information Age that no one is more capable at framing and shaping events and ideas from a particular point of view or set of values than the large tech companies. These entities possess a worldwide audience of billions of people every minute of every day.

Many, including me, have completely morphed their media habits over the last couple of decades and now look to social media as a guide for world events instead of reading newspapers. Cognitively, many of us know that in order for tech to provide personalized experiences that may seem more convenient in the short term, they may make ethical compromises related to transparency, data collection, privacy, user autonomy, and other exploitative practices designed to manipulate us.

Nevertheless, in aggregate, we tend to ignore these trade-offs. Whether it’s swaying elections, pressuring for the mass experimentation on humans with novel drugs, or denying biology as a mere construct, given the sheer size of their audience combined with algorithmic and other technological capabilities, it is indisputable that Big Tech plays an outsized role to socially engineer our society.

Sometimes this stewardship comes from directing our attention to so-called experts whom we are supposed to follow for guidance. In other instances it’s merely lying by omission by presenting only one side of the conversation to give the illusion of consensus. Recent examples include Covid, climate change, gender-affirming care, and a number of other social and political issues.

One might argue that if there really were legitimate dissenting views on any of these controversial topics, investigative journalists would surely be exposing the truth to us. After all, it is the sacred duty of the Fourth Estate to provide citizens with information to keep the power structure in check. I used to think that.

Even if there are assiduous reporters working at large news organizations, it is obvious to anyone who’s been watching the rampant censorship within Big Tech over the past few years that the institutions who distribute the stories to the public are subject to the oversight and control by the United States Government.

The prevailing wisdom in dissident circles is that social media platforms’ censorship of voices unfriendly to government narratives represents some sort of recent institutional capture. But what if the oversight or pressure from the government to “content moderate” is not a result of recent capture and not a new phenomenon? What if it is a manifestation of a longer-standing government plan to fund the start-ups of these powerhouse companies with a view toward making nefarious use of them later?

If you think this sounds too far-fetched to be true, consider that the federal government that was recently found to collude with Big Tech to interfere with free speech is the very same institution that ran Operation Mockingbird, a covert CIA project designed to bribe individual journalists and worldwide media organizations in order to affect public opinion through the manipulation of news reporting.

In an investigative analysis by Carl Bernstein in 1977, the CIA admitted that at least 400 journalists and 25 large organizations around the world had secretly been bribed to create and distribute fake news stories on behalf of the agency. Since then, the technology that can be used to modify and even control our thinking has become orders of magnitude more powerful, refined, and sophisticated. Keep this in mind as we go through a quick thought exercise.

Before we do, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that even the mere possibility of the web being a trap hits close to home because not only do I absolutely love the Internet, but this field is how I’ve supported myself and my family since I was a young man.

When I started doing this work in the mid-90s, I thought I was a cynical person who asked critical questions, but in reality, I was a youthful wide-eyed optimist. I genuinely believed in the earnest notion of combining hard work with luck and in the idea of founders building independent world-changing companies.

In fairness, I do know many people who did just that. However, an exploration into the major tech companies which make possible the web’s superpowers raises some questions about their roots, and whether their meteoric rises were in fact organic.

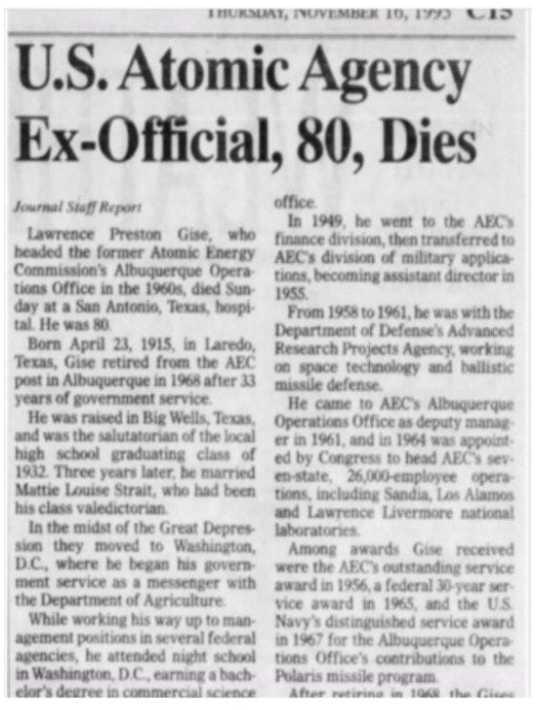

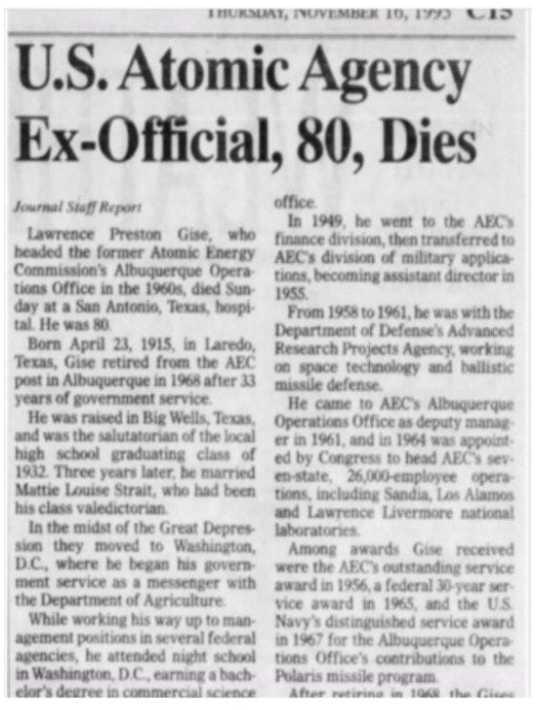

Let’s start with Amazon. Jeff Bezos’ grandfather, Lawrence Preston (L.P.) Gise, was Director at the Atomic Energy Commission, and helped to form the US Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), from which ARPAnet evolved. During his tenure, Gise approved and provided funding for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) – which would eventually invent the Internet.

It makes sense that Bezos might grow up to have interest in this area. After all, if your grandfather was a founding father of the internet, I imagine you might be drawn to the web too. But why hasn’t this part of the Amazon CEO’s history been widely publicized?

I’ve read a lot about Bezos through the years and he’s most often described simply as a hedge fund guy with a great idea. Perhaps that’s true, but it is interesting that even puff pieces about Bezos learning his technical skill from his grandfather omit his forebear’s early internet connections.

The Amazon founder gives other examples of his grandfather’s work ethic and self-reliance. One summer, the two built a house from scratch and he also recalled helping his grandfather fix a broken bulldozer.

It is possible the author wanted to focus on the folksy DIY angle, but while “Pop” Gise may have been a resourceful homesteader, he was also one of the pioneers of one of the most important technological innovations in human history – not to mention the infrastructure on which Jeff built his empire. If I were writing about how young Jeff was influenced by his grandfather, that feels quite relevant.

Interestingly, Jeff’s Wikipedia page mentions that his grandfather was “a regional director of the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in Albuquerque” but it doesn’t mention DARPA or the internet. Bezos’ mother’s entry doesn’t even mention L.P. Gise by name. Is it plausible that these omissions are simply clumsy oversights?

While Amazon ostensibly started out as an online bookseller, it has evolved into what can arguably be called a full-service data collection vehicle. They collect your personal information via your online store orders of items physical, virtual, and pharmaceutical. Amazon can see who is coming in and out of your living space with Ring, acquired in 2018, and has the technical capability to listen to conversations of more than half a billion people through Alexa devices installed in homes, offices and dorm rooms. Most recently, Amazon has added One Medical which provides 24/7 on-demand virtual care from “licensed providers” and for those who live near brick-and-mortar locations, in-person visits. Customers are assured that their information is confidential, but would it remain so should the government bring pressure on Amazon to give it up in an “emergency?”

Just last year, Amazon settled a $30.8 million lawsuit for claims that it improperly retained children’s Alexa voice recordings and Ring videos, along with related geolocation information, for years – in some cases without consent and despite requests by consumers for the data to be deleted. They also enabled employees of its Ring video unit to survey customers. One Ring employee viewed thousands of video recordings of female users of security cameras that monitored bedrooms and other private spaces in their homes, the Federal Trade Commission said in a complaint. In a separate incident, the company was recently fined in France for their rigorous employee surveillance program. That same intrusive system was also cited in a study as the cause of suffering physical injuries and mental stress on the job.

Perhaps because of their embarrassing failures, Ring recently succumbed to pressure from privacy advocates who criticized them for letting police departments request users’ footage without a warrant. They eventually did the right thing and respected their customer’s privacy, but given Amazon’s very close relationship to the federal government as a provider of cloud services, what happens when the lettered agencies call asking for warrantless audio and video footage from someone’s private life?

Now let’s consider Google, a company that many people believe to be an unquestionably reliable source of facts and arbiter of truth. The popular origin story of the web search titan is that it was the brainchild of two scrappy boy-geniuses at Stanford who were looking for a better way to find and present the ever-growing depth and breadth of information being uploaded to the web.

Conspicuously missing from that official story is the part about how Google started in 1995 as a DARPA-funded grant project for the CIA & NSA joint Massive Digital Data Systems Program.

While the company’s Wikipedia page details the account of how they got seed funding from a few Silicon Valley luminaries, it fails to mention that some of the research that led to Google’s ambitious creation was funded and coordinated by a research group established by the intelligence community to develop and implement ways to track individuals and groups online. If that part of the account hadn’t been erased from the history books, do you think Google would have quickly gained the trust of billions of people around the world?

While I never bought into their over-the-top “Don’t Be Evil” schtick, I naively believed that people leading the company were motivated primarily to improve the planet by offering global access to the world’s information. Maybe that’s true…but, Google turned out to be a pretty darn good spying vehicle too.

There was a time when my unsophisticated brain thought the power Google maintained was merely to suck in all of our data to manipulate us with advertising, but it’s become so much more. As their services have expanded to mail, geolocation, content publishing, AI, telecommunications, payments, and seemingly everything else one would need for managing all facets of their digital existence, it’s become apparent that search was merely the on-ramp for their data capture enterprise.

This makes sense when you consider the central role search engines play in modern life. For the first time in human history, people in every country in the world willingly ask machines questions and perform queries about everything on their minds. These inquiries can range from mundane trivia to how-to content to more confidential things like highly private health concerns.

Google’s ties to intelligence have continued beyond the very early days of the company. In 2004 they bought Keyhole (now Google Maps) from In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s investment arm also backed by the FBI, NGA, Defense Intelligence Agency, and others. Do you think this was a straight-up financial transaction or is it possible that there were strings attached?

Other intel ties include Google and the CIA co-investing in assets like Recorded Future, which monitors the web in real time in an attempt to create a “temporal analytics engine” (a Minority Report-style program that makes predictions about future events), and Google’s participation – along with other tech giants – in the NSA’s PRISM program, which collected data from users on their platform without users’ permission or a search warrant. In 2006, the company launched Google Federal to serve government contracts. This division in the company had so many former NSA staffers that it was often referred to as NSA West.

More recently, it was uncovered that Google employs more than a few former CIA agents and other ex-high level government employees in key roles including those who determine “what content is allowed” on their platform.

As civilians, most of us think we’re searching the entire web, but Google has acknowledged that they are presenting only what their censors, partially made up of former intel agents, decide is appropriate. Based on the PRISM revelations, it’s also apparent that the content we do consume has, at least for a period, illegally been shared with our government. Sweet.

To further illustrate how internet companies can be quite cozy with government and intelligence agencies, consider these fun tangential facts related to the (pre-Google) early days of web search: Ghislaine Maxwell’s twin sisters, Christine and Isabel Maxwell were the founders of Magellan, one of the first search engines on the internet (eventually, acquired by Excite).

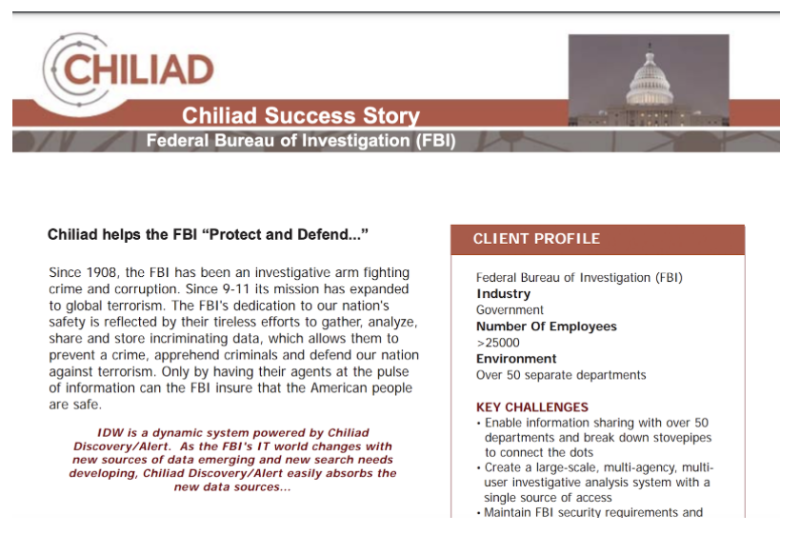

After Magellan, Christine started Chiliad, a data mining company working with the CIA, NSA, DHS, and FBI on “counterterrorism” efforts. During this time, Isabel’s company Cyren (previously Commtouch) had some very sketchy ties to Microsoft and Silicon Valley companies, allegedly possessing a backdoor into them. Christine now serves as UK and US Technology Pioneer for the World Economic Forum.

The Maxwell sisters’ father, Robert, was widely rumored to have ties to organizations including MI6, KGB, Mossad, and the CIA. It is not fair to surmise his entrepreneur daughters were in the espionage business by mere association with their father and infamous sister – or even because of their contracts with the intelligence agencies. Still, it feels noteworthy.

What is clear, however, is that since the early days of search all the way to the present, the fact that we often don’t think about who or what is on the other side feeding the results in this curiously intimate relationship with the search bar is arguably a feature not a bug.

If search is the brain tapping into the collective consciousness of what people are looking for online, social media is the soul, monitoring and connecting users based on what they’re sharing. The former is predicated on intent whereas the latter is more about identity and interests.

While both can be used as tools to amass a trove of data, search is more transactional since the user performs a query, finds the results and moves on, whereas social is more about creating virality and binding people together through the social graph.

The Pentagon (specifically, DARPA) apparently foresaw the usefulness of collecting the breadcrumbs of people’s behavior when they started working on LifeLog, a project to track a person’s “entire existence” online. It’s ambiguous what happened but they shut the project down on Feb 4, 2004.

As fate would have it, that same day – February 4, 2004 – was the day that Facebook (then, TheFacebook) launched at Harvard. That is a weird coincidence that Aaron Sorkin didn’t mention in the movie version, but it’s probably nothing. DARPA even denied having a connection, so I guess we’ll have to take them at their word.

Like their cohorts at Google, Facebook seems to be hiring from the intelligence community at a rapid pace. Recruiting from agencies including the CIA, FBI, NSA, ODNI, as well as other government departments including DOJ, DHS, and GEC, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, has hired more than 160 former intelligence employees since 2018. Collectively, many of these employees are involved in the so-called Trust & Safety team (naturally) determining what content gets amplified, fact-checked, and/or taken down entirely.

When Matt Taibbi, Michael Shellenberger, and other journalists released the Twitter Files last year, it became unmistakable that Twitter was yet another Big Tech platform that had direct ties to the US surveillance apparatus.

Similar to Google and Facebook, they also had a number of ex-spooks under their employ, including an alarming number of FBI agents. It is unclear if and how Twitter (no, I still won’t call it X) has been working with the government since Elon Musk took over.

There is, however, an overwhelming amount of evidence that prior to the acquisition, the government exerted influence on the company to create guardrails around the content that got presented and even flagged specific users as being potentially dangerous. That is a lot of power to wield in shaping the hearts and minds of the masses.

This might just be another odd synchronicity but Project Bluebird was the original codename for what became the government’s MK Ultra Mind Control Program. Goals for Bluebird included “obtaining accurate data from persons willing and unwilling” and “increase compliance to suggested acts.” It’s interesting to consider that in the context of the iconic – and now retired – company logo. Who knows if that’s just a creepy coincidence or some sort of signal that insiders have been aware of all along?

So, are all the official origin stories of tech companies finessed at best, entirely fabricated at worst? There sure are a lot of uncanny ties to the intelligence community and this essay just scratches the surface. Maybe they’re all just coincidences but in doing a little research, these parallels caught my attention so I thought it worth pondering.

If the intent behind these organizations was always a myth, personally, I feel as duped as anyone. I worked in tech for decades before tapping out when realizing many of the people coming into the field were no longer idealists wanting to democratize the world’s information. Instead, they operated more like cartoonish bastard children of Hollywood and Wall Street.

Still, until the last few years, I didn’t understand just how sinister these corporations might be in their participation in activities beyond generating a profit for their shareholders. For a while I’ve understood the danger we face from the banksters, Big Needle, traditional media execs, etc., but I didn’t truly comprehend that the world I thought I lived in was, in large part, an illusion. After all, we live in a society overrun with fake money, fake foods, fake news, fake wars, fake credentials, fake medicines, so why would the giant foundational companies on the Internet be any different?

Regardless of whether the ascent of these Internet behemoths was a deception or not, they are now incontrovertibly in cahoots with the Data Industrial Complex. Whatever one might think of TikTok, the debate around whether it needs to be brought under US ownership or else banned does beg the question of why United States ownership is so crucial right now.

Is there genuinely a national security risk being addressed or do legislators – and more importantly, their donors – simply want it to be under American jurisdiction so they can control it like they do the other large tech companies? I think Brownstone’s Jeffrey Tucker best summarized our choices with this tweet the other day:

If there are any silver linings here, it is that many people are waking up and demanding transparency and authenticity – and seemingly no one is going to the other side. A truly woke society will be glorious. The only question is are there enough of us before the unsuspecting masses get so propagandized they morph into the borg. I sincerely believe this is one of the defining issues of our time.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.