The image of Escrava Anastácia has been making many appearances in several recent anti-lockdown protests around the world. The way in which the likeness of this muzzled female Brazilian slave has been used to illustrate the various forms of pandemic population restrictions, particularly the mandatory wearing of face masks, has been criticized by various media outlets for its perceived cultural appropriation and irreverence to the historical suffering of black people.

This article represents an opportunity to address this claim of cooptation and to explain the merits of illuminating the current health-driven limitations as indeed a form of enslavement.

Anastásia speaks in the silence after prayers, as if telepathically. I think I can make out of the sound of certain words… Anastácia’s silence says: “Speak for me!”

Escrava Anastácia is a folk saint venerated in Brazil, with a large number of devotees among Umbanda practitioners. She is also venerated by many black Brazilian Catholics, having an important shrine in the prominent church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black People in Salvador da Bahia, even though she has never been acknowledged or canonized by the Roman Catholic Church.

A popular prayer to the folk saint reads as follows:

Anastásia, you who suffered the evil of the lords of plantation and were one of the martyrs of captivity, Become onto us a benefactress in times of affliction and anguish.

In our hearts that suffer the bitterness of bad fortunes and the harsh blows of our destiny,

You who are worshiped by a legion of devotees for your miracles.

Help me in this moment of despair, affliction and distress, taking me out of this unpleasant situation that I am now going through.

Remember your last earthly existence and you will know how to empathize and recognize my misfortunes… Lighting this Candle for you, symbol of my FAITH and my trust, allow me to make a request; it is about the following: [Expose the problem, health, financial, bad situation, love mismatch, etc….] If you tend to me, I promise to remember you with all respect, veneration and affection. I hope so .

So be it…..

Into the preceding brackets, I might insert the following:

Blessed Anastácia, How do free speech and academic freedom protect me from institutional retaliation as a result of questioning the mask mandates? You who come swiftly to the aid of all who speak courageously in the face of censorship and silencing, cover me!

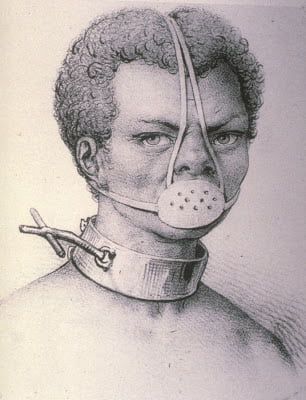

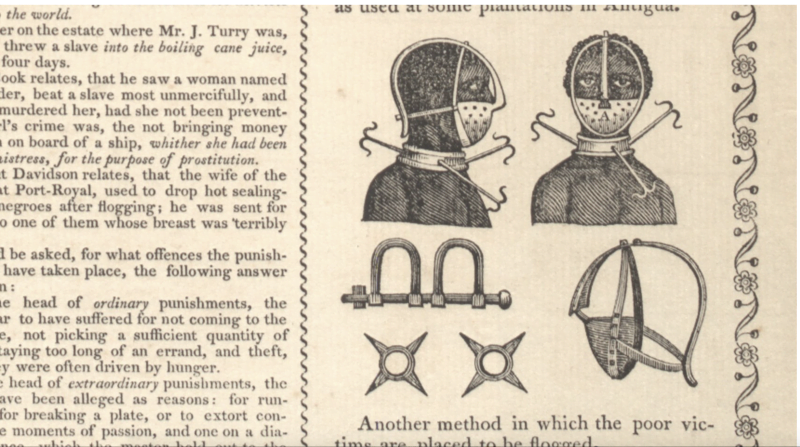

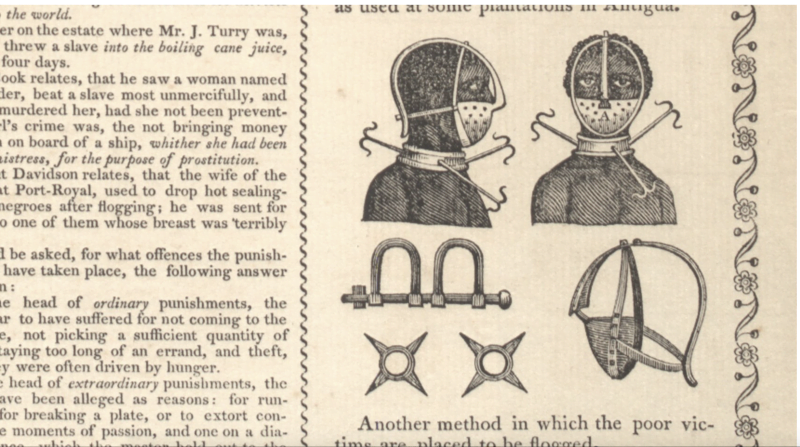

Her hagiography includes multiple stories that emphasize the nobility of her character in spite of her discursive and physical muzzling by the oppressive power of the system of chattel slavery. In some stories she is the mixed race child of an African princess and a slave trader who is fitted with a metal muzzle to prevent her from revealing the trader’s infidelity and the rape of her mother (Burdick 1998).

In other stories, Anastácia is herself the victim of rape, or at least attempted rape, by a slave planter who also punishes and silences her with the metal contraption. In some versions of the story, the mistress of the plantation muzzles Anastásia to save herself from any public shame that could come about by the disclosure of her husband’s infidelity. In yet other variations of this story, the reasons for her muzzling involve the aid she provided to a runaway slave and her leadership in organizing a slave revolt.

In all of these narratives the muzzling seeks to silence her cries against injustice and a voice that leads to liberation. As a form of public shaming, it serves as a deterrent for those slaves in the plantation who could be inspired by Anastásia. Her martyrdom comes about either through starvation or from the tetanus produced by the metal as it rusted in her mouth. Her ability to perform miracles, even while muzzled, included healing her oppressors.

This presents an idealized martyrdom, an admirable resilience as well as a moral impermeability to and an ultimate victory over the downpressure of slavery. Her compassion towards her persecutors as well as her alleged mixed-race background is seen by many devotees as a hopeful sign of racial reconciliation in Brazil and in all lands affected by the slave trade.

Blessed Anastácia, my co-workers, faculty and staff have reported me to the department Chair for sighting me in the building’s common areas without wearing a mask! Yeah, being good Pavlik Molozovs (Catriona 2005)! I haven’t experienced such a snitch culture since communist Cuba! Their concern for the “the lives of others”(Henckel 2006) is just too reminiscent of Eastern Bloc techniques of social control for me to continue to interact with them. You who were turned in by an informant at the plantation, have mercy on us!

The apparition of Anastásia at anti-lockdown rallies represents an opportunity to understand the current medical tyranny as a form of enslavement and to forge links of solidarity between communities whose freedom is threatened across all racial groups. The claim of cooptation deserves to be unpacked for a valid claim of cultural usurpation could easily work towards severing important alliances in a divide-and-conquer model.

While there are clear specificities between the suffering of Africans under the system of chattel slavery and the deprivation of civil liberties endured by most citizens around the world during the current pandemic panic, Anastásia reminds us of certain transhistorical constants in the process of dehumanization and subjugation of populations through the gagging and muzzling of their bodies to quell their protestations.

Let Anastásia speak for freedom today!

Blessed Anastácia, Whenever I speak about the irrationality of masks being able to filter viruses, I am quickly shut down by people who tell me that I am not a medical doctor and therefore have no right to speak on the topic! You who understood how despotic and coercive power works to silence dissenters, strengthen our resolve to boldly speak the truth in the midst of lies.

While it is outside the scope of this piece to discuss in detail the effectiveness of masks to prevent infection by airborne pathogens, I do want to stress that the data suggests that their use for this purpose is questionable. I would like direct those with a keen interest in “following the science” on masks to the latest WHO-funded study, published in a peer-reviewed medical journal, available on the CDC website proving that “face masks have not demonstrated protection against laboratory-confirmed influenza” (Xiao et al. 2020).

The inefficacy of face masks to contain upper respiratory infections was the official policy of the WHO and the CDC prior to the current health panic (Molteni and Rogers 2020) and continues to be confirmed by ongoing research (Guerra and Guerra 2021).

Blessed Anastácia, I find myself unable to enter into supermarkets because of my refusal to wear a masks. You, whose mask prevented you from eating and ultimately died of starvation, have mercy on us!

While the medical effectiveness of mask-wearing in the current pandemic cultural climate is dubious, the social and psychological elements of control enacted by compulsory masking are much clearer. What are the effects of masks on the psyche of those forced to live under the current medical tyranny? That the dictates on masks are coming not largely from immunologists but from what very well appear to be compromised behavioral psychologists such as Susan Michie, who is foretelling that we will be wearing masks forever (Stone 2021), forces us to consider that masks are less driven by health reasons and more by the malevolent use of Pavlovian and compliance studies knowledge to break down the psyches, dignity and integrity of individuals and the social coherence of societies, rendering both more susceptible to manipulation and reconfiguration according to norms conducive to their own subjugation.

The mandatory use of face masks during the current health panic fashion the citizenry as slaves. As symbols of enslavement,

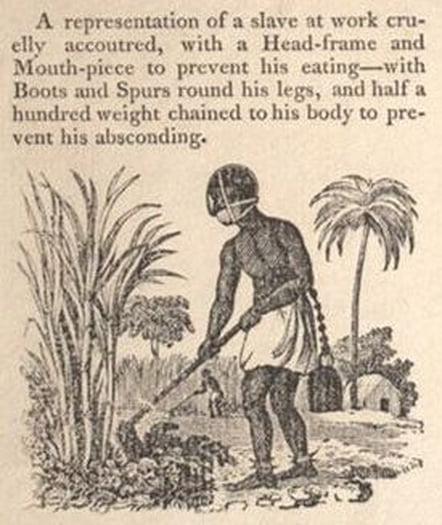

- Masks deprive us of oxygen. They produce hypoxia, leading us to a state of physical and mental weakness in which the population is more prone to ideological brainwashing and less capable of ascertaining the degree to which they are oppressed.

- Masks are symbols of submission. Their medical practicality is very questionable, yet people are forced to wear them. Despotism is established in the forced compliance of arbitrary rules. Caligula planned to make his horse a consul just because he could.

- Masks are the lurid fetish of power. Given that face masks feature prominently in bondage and sado-masochism (BDSM) role play, which is invested in master-slave dynamics, can we not see the powerful psychological element of subjugation that they represent for those who are forced to wear them? Can we consider the perverted delight that the sight of these mask wearers brings to the schemers of these policies?

- Along with lockdown, masks enforce the creation of a carceral culture. The terminology and aesthetics are borrowed from prisons, especially those in which torture features prominently. Recall the hooding of Abu Ghraib prison torture victims and the mouth covers on those at Guantánamo. If we can consider the historical transmutation of the slave plantation into the prison, we can perceive the persistent and insidious dehumanization of captive and enslaved populations through masking—a technique of domination aptly articulated in the title and text of Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks.

- Compulsory masking leads to the erasure of personhood and the homogenization of masses. The collectivized wearing of masks results in an enforced uniformity in which the individual cedes way to the nameless collectivity as the neo-meta-citizen.

- Masks are theatrical. They have been used for millennia for the investigation and recrafting of personhood. The very word “person” has an etymological source in the name for the masks used by actors in ancient Greek theatrical productions. As theatrical props, masks conceal and obfuscate our identities, rendering us alien to others and ourselves.

- Anthropologically, masks play a role in the crafting of liminal identities. As such, they are not in-and-for-themselves, but prepare the individual for their new roles in society. The masks shape the individuals’ subjectivities. They can be removed when their program has been assimilated by the newly recrafted individuals. However transitory the current regime of face masking might be, the population must face that we are being forced to undergo a rite of passage, a process of resocialization into the new normal. The more we accept that we are participating in the ritualization of our dispossession and enslavement by wearing the mask, the less able we will be able to don it.

- The masks are state insignia. They are a visible display of allegiance to the system of medicalizing technocratic control. Just as the red neckerchief of the communist pioneer youth movement publicly professed loyalty to the one party and the most supreme leader, the face mask is the symbol of political adherence to new normal, confirming conformance to “right thinking,” à la Mao Zedung.

- The deletion of facial expression inhibits non-verbal communication necessary for social organization that can lead to revolution. The masks seek to deactivate our revolutionary potential.

- Verbal muzzling: The masks reduce overall verbal output. Along with enforcement of (anti) social distancing, their usage foments the isolation of the individual and the atomization (Arendt 1951) of society into ineffective rebels, unable to consolidate into coherent units under a common discourse or banner.

- The associations that symbolically and functionally masks bear to muzzles speaks to the dehumanization and the domestication of the population under these directives.

- Just as masks function as liminal artifacts in rites of passage and as part of animal training, these covid mask are harbingers of further intrusions to our integrity. Wearing the masks is just one step away from receiving the shots, then accepting the vaccine passports and the implantable neural links until one’s original persona is buried by a cyborg. The masks function as an empirical compliance test for the projected acceptability of future corporeal technologies of control. Where will you draw the line?

- Masks promote a culture of fear. Each and every mask is a billboard advertising a state of emergency, putting individuals in a constant sympathetic nervous system fight-or-flight mode that reduces their field of possibility to focus on the presumed ever present threat of infection. Meanwhile, the oligarchical system of domination erodes our civil liberties across the world. Masks are part of the politics of subjugation through scaremongering.

- Masks are deterrents of solidarity. They promote the constant perception of your neighbor as a nameless pathogenic vector instead of your ally. The masks divide and conquer.

Anastácia’s silence says: “Occupy!” What does this mean, I ask. “Occupy the space that’s been allotted to you.” Does this mean to use my current position in academia as a platform from which to challenge the collective hysterical delusions of this political health panic? Anastácia enigmatically but firmly re-states: “Just occupy…”

Mainstream media reports have criticized the deployment of the effigy of Anastásia in lockdown rallies by categorizing them as instances of cultural appropriation (Villareal 2020, Da Costa 2020). No is allowed to make use of the imagery of chattel slavery to describe the lockdown measures without being smeared as a racist, especially if they are white (Chesler 2021).

Could it be that power chastises those who ask whether our current deprivations of liberties are akin to slavery because there is an element of truth of in the question?

This cultural appropriation argument presents Anastásia as having been hijacked and decontextualized by dominant social elements who do not have a stake in her politics of racial liberation. These reports focus on the whiteness of the protesters holding up the black slave’s image as evidence of something incongruous that speaks to co-optation and theft.

However, none of these reports care to elaborate upon the hagiography of Anastásia to any significant depth or to unpack the symbolic layers that her life-work embodies. For articles that claim to care deeply about the misuses of Afro-diasporic lives, these omissions are nothing short of problematic. Instead of using these instances to probe into the curious appearance of images of Brazilian folk Catholicism in the industrialized world and to inquire into the various forms that slavery might take, the authors essentialistically present the protesters as racists in order to avoid making the obvious correspondences between chattel slavery punishments and lockdown sanctions manifest.

Shouldn’t those who see the analogy as hyperbolic at the very least concede that the strategies of silencing in these two systems of oppression are uncannily similar? In order to circumvent the inconvenient presentation of the current medical tyranny as a revisitation of earlier generally condemned systems of control and to steer clear of the unflattering reflection of ourselves as slaves under this new system, the articles resort to a curious rhetorical strategy: they use an ad hominem attack that discredits the source of the argument by focusing on the ethnicity of the protester while at the same time never confronting the core of the argument presented.

That the attack led to an apology by the California female protester makes me draw an even more powerful connection between Anastásia and her as pillared subjugated women, in spite of their racially different backgrounds. In addition to shutting people up, masking has the effect of inducing and performing an identity of shame and punishment for a social trespass, displaying visibly the consequence of a guilty sentence as a deterrent for others who might dare to protest their silencing. The pressure experienced by the protester to apologize is analogous to the mandate to wear the covid mask and the slave muzzle. All have the purpose of silence dissent. The retraction of the accusation is evidence of the crime.

Anastásia says: “Take me with you!” “Where,” I ask? “To the protest in Trafalgar Square? Do you want to march down Oxford Street with the protesters on Saturday?” “In your heart,” she says. “In your heart…”

Indeed, there is a “Covidian Cult” (Hopkins 2020). I would like to add to the conversation instantiated by his provocative phrase by questioning the presumed negativity associated with this kind of religiosity. Within the study of religion, “cults” have been euphemistically rebranded “new religions” in order to be more relativistic and less judgmental, bowing perhaps to the exigencies of political correctness.

Regardless of the term we choose to use, the role of ritual, dogma and the inquisitions and pillorying of those who, questioning covid orthodoxies, commit the sin of blasphemy, all display a drive that is concomitant with the most brutal aspects of religions across the centuries. Yet, realizing the power of religious discourse, could we harness it to productive ends? Could we employ our judgement to become more cognizant of our own uses and abilities to deploy religious iconography towards the ideal of freedom?

Can the cult of Anastásia overcome the Covidian cult? By asking these provocative questions I don’t intend for us to literally recreate the freedom movement as a new religion; instead, I urge us to realize the tremendous power that neo-religious performance, ritual and spectacle hold, the double-edged swordedness of it, our own incipient deployments of such iconographies and signal to our full use of the language of spirit, whose synonym is also freedom. And for those of us among the freedom movement with some form of spiritual practice, especially those with a Christian formation, the biographical and visual portrait of the non-canonical Anastásia can help to illustrate what many of us feel: that there is a metaphysical element in all of this, that to say otherwise is to be “denying the demonic” (Curtin 2021) as it looks like we “wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” (Ephesians 6:12).

Anastásia says that when they shut you up, the power then flows through your hands. The power is not in the words; it’s in the action-inaction. What does she mean by working with the hands without doing? Truth cannot be impeded. It will polish rock. It will carve a big canyon. It will flow. When silenced, extend out your hands…

Detractors of this equivalence I am making between the mechanisms of chattel slavery and the covid restrictions on civil liberties will point to the specificities of each system of domination and rely on the inexactness inherent in analogies to make their case.

Anticipating such arguments, I will stress that slavery takes many different shapes in different spatial and temporal contexts. If in the pre-industrial era, the shackles, balls and chains were made of iron, in a technological age marked by the invisible transmission of data across space, the mechanisms of enslavement become more evanescent, as thin as thread, as diaphanous as cloth.

Lightweight as surgical masks might be, their weight on enlightened psyches can be felt just as heavy as Anastásia’s slave bit. Cloth can be as corrosive as rusting iron on the skin of the awakened whose conscience is cognizant of its suppressing and censoring intent. Certainly, the chattel slavery endured by African-descent people in the early modern period is not exactly the same as the control over people’s bodies that the new normality seeks to impose. But if we fail to see the continuities and refuse to see beyond symptoms and surface, we deny ourselves the ability to perceive the transmutations and adaptations that slavery acquires in every age.

Those who refuse to see the current masks mandates as a technology of enslavement are deceived by camouflage. The chamaeleon-like nature of slavery is one of its enduring survival tricks. So varied are the forms of slavery that its foremost theoretician is at great pains in providing a working definition of it. For Orlando Patterson, in his Slavery as Social Death, what makes chattel slavery singular is the concept of “social death” in which the enslaved is denied connection to a place of origin and to ascending and descending generations.

The black slave in the Early Modern Americas is a fractional, quasi/non/sub human without citizenship or family. It seems evident to me that the limitations of vocal and visual interactions of masks render analogous socially dead subjects. The erasure of half our faces produces a fractionalization of our subjectivities. It is an attempt against our sense of personhood and that of our neighbors’, who we are increasingly expected to consider potential threats to our health.

The imposition of this masking onto the population results in a uniformed and homogenized population, in which collectivities are visually and legally no longer a collection of individuals—for what else are individuals but selves who have enacted choice?—but instead indistinct masses, muzzled and compliant throngs. The muzzled are slaves for they have lost a part of their personhood. It is common among these slaves to refuse to see their masks as reductions of their selfhood or as anything akin to slavery. It is embarrassing to see yourself when you have lost face. The darkness of the frightened-ostrich-head-in-the-hole is preferable. There are none so blind as those who will not see.

Most people who lived through the Early Modern period on both sides of the Atlantic rationalized slavery as natural condition. Most regrettably, this ideology was instilled among the enslaved, leading many people of African descent to accept their bondage in New World plantations. This is why I am not surprised to see how most people around the world seem oblivious to their subjugation during the current regime of domination.

Shakespeare provides us with dramatization of just how this brainwashing occurs. In The Tempest (1611), Caliban is enslaved by Prospero through his incantations. Prospero uses magic charms to confuse and convince Caliban that his rightful station is that of a slave. When Caliban demands a rational explanation for his enslavement, Prospero guilt trips Caliban into believing that he attempted to rape Miranda, Prospero’s daughter.

A similar element of the discursive uses of the enslaving evil eye can be studied in Hegel’s “Discourse of the master and the slave” (1807) in which mythically, the slave is constituted as such as he loses the battle with the would-be-master. As the master spares the slave’s life in the duel, he convinces the slave that his life is no longer his own, that he has died to himself and must only live for the master. The role that guilt plays in suppressing the innate longing for freedom is echoed in the countless ways in which the current medicalized regime of power brainwashes the masses into accepting their endless confinements and sequestrations.

How many times have we heard the new normies decry the excesses of illegal mass gatherings and so called super-spreader events as the reason for the limitations on our civil liberties? Under this rhetoric, the population deserves lockdowns. They have brought it down upon themselves for having succumbed to the temptation of contact with the pathological dangers inherent in nature and their fellow human beings, seduced by the sunny weather into congregating in beaches and parks allegedly infested with pathogens.

Shakespeare’s Caliban and Hegel’s slave are manipulated through remorse for their putative moral inadequacies (attempted rape, pugilistic weakness) into believing that they are responsible for their current demotion in status and therefore must nobly endure the limitations that they have brought upon themselves. Anastásia’s informant and betrayer was one such slave who, having internalized the ideology of enslavement, signaled her virtue and allegiance to the system by turning her in for having helped a fugitive. If through this analogy, the new normies function as brainwashed slaves, then those of us in the freedom movement can find inspiration in the figure of Anastásia who pointed towards the route to freedom, and ultimate identification in the figure of the maroon runaway slave.

The internalization of blame for their own suffering is the most important constitutive elements of the blindness that prevents many of our contemporaries from understanding the curtailment of our constitutional liberties as a form enslavement. The ability to deconstruct and rebuff this false ascription of guilt is the foundation of our liberty. Our freedoms of expression, assembly and religion are not granted to us: they are inalienable. The transcending of this blinding, unfounded and debilitating guilt lie at the heart of the awakening of the currently sleeping masses. Understanding the current health scare as a delusion brought about by Prospero’s cheap tricks, the unreasonableness of the prison-derived concept of lockdowns and the psycho-socio-somatic masking that attempts to silence those who prophecy against medical tyranny and all tyrannies is the spirit of Anastásia today, alive in our midst.

It seems fitting that the Spanish language would use the same word to refer to a newly arrived slave as to a muzzle. The word “bozal” designates both a recently disembarked slave, one who was born in Africa as opposed to the “creole” slaves born in the New World colonies. That this same word should be used to refer to a certain kind of slave and to the muzzle worn by domestic animals like dogs signals to the historical use of these devices on these slaves who had had a taste of freedom, the ones who had memories of liberty in an ancestral land.

These bozal slaves were the most likely to lead rebellions, as the myths surrounding Anastásia illustrate. For speakers of a language in which the word for a kind of slave also indexes a mouth covering, this polysemy implies that at some subconscious level there is a realization that the politically-mandated mask is a symbol of their enslavement. Their laughter when confronted with this linguistic coincidence begs to be read as an evacuation of psychological anxiety and uncomfortable recognition. Regardless of the languages we may speak, many of us know and suspect that there is something performative in the wearing of the mask, that we are being coerced to take part in a bal masqué in which constitutive elements of our identity are being reshaped in ways that work against our best interests. Regardless of the language you speak, the message of Anastásia is intelligible to you as part of the conscious resistance.

You remember having run into the hills I signaled to you a few centuries ago, when we lived in Brazil, don’t you? At my prompting you are starting to remember that beautiful and prosperous colony of runaways, that Palenque in the cool and fertile tropical highlands, you helped to establish, from which you raided the Portuguese settlements and eventually secured the freedom of countless of our brethren? You remember. In my silence, remember. You are free. You are freedom!

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Shocken, 1951.

Burdick, John. Blessed Anastácia: Women, Race, and Popular Christianity in Brazil. Routledge, 1998.

Catriona, Kelly, Comrade Pavlik: The Rise and Fall of a Soviet Boy Hero, Granta Books, 2005.

Chesler, Josh. “Eric Clapton and Van Morrison’s Anti-Lockdown Track Is Out Now.” Spin. 12/18/2021.

Curtin, Edward. “Denying the Demonic.” Off-Guardian. April 18, 2021.

Da Costa, Cassie. “White Anti-Quarantine Protesters Have Cruelly Co-opted an Enslaved Black Woman from the 18th Century”. The Daily Beast. 5/22/20.

Frantz Fanon. Peau Noire, Masques Blancs. (Black Skin, White Masks). France: Éditions du Seuil, 1952.

Guerra, Damian and Daniel J. Guerra. “Mask Mandate and use Efficacy in State-Level COVID-19 Containment.” MedRxiv. 05/18/2021.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The phenomenology of spirit. Cambridge Hegel Translations.

Translation of Phänomenologie des Geistes (1807) by Pinkard, Terry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Henckel von Donnesmarck, Florian. The Lives of Others / Das Leben der Anderen. Bayerische Rundfunk, 2006. .

Hopkins.C.J. “The Covidian Cult.” Consent Factory. October 13, 2020.

Molteni, Megan and Adams Rogers. “How Masks went from Don’t Wear to Must Have.” Wired. 07/02/20.

Patterson, Orlando. Slavery as Social Death. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1982.

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. 1611.

Paul of Tarsus. “Epistle to the Ephesians.” New Testament.

Stone, Josh. “Face masks should continue ‘forever’ to fight other diseases, says Sage scientist.” The Independent. 06/11/2021.

Villareal, Daniel. “California Woman Apologizes for Holding Sign of Lockdown Protest

Comparing Wearing Masks to Slavery.” Newsweek. 5/21/2020.

Xiao, J., Shiu, E., Gao, H., Wong, J. Y., Fong, M. W., Ryu, S….Cowling, B. J. (2020). Nonpharmaceutical Measures for Pandemic Influenza in Nonhealthcare Settings—Personal Protective and Environmental Measures. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 26(5), 967-975.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.