I will readily admit that I am not a mask expert. I haven’t done research on the efficacy of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Instead, my expertise is in animal models of immunity and infectious disease. But I did have an opinion on how masks would be used in a pandemic before COVID-19, and that opinion was formed during my time working in proximity to PPE experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (CDC-NIOSH). And when, during the pandemic, policies regarding the use of masks for the public took a sharp turn away from what I had envisioned, I became very curious about why that happened. Did I miss something? Was I completely misremembering what I had been told?

So I began to follow very closely what scientists and leaders were saying and writing regarding mask usage, and how that had changed before and after the push for universal masking. Fortunately, we live in an age where information is difficult to erase completely. So the record is still (mostly) there, for those that look closely and carefully.

Based on what I knew in March, 2020, masks were more effective at blocking large (>5um) respiratory droplet particles, the kind more likely to be emitted by symptomatic individuals that are coughing or sneezing. In contrast, smaller aerosol particles (<5um) are more difficult to block with cloth or surgical masks due to poor filtration and outward leakage. This is complicated by the fact that there are large differences reported with the efficacy of masks in particle blockage/filtration in controlled laboratory studies. But the general consensus was that masks would not be an important tool for mitigation during a respiratory virus pandemic.

Before Things Got Political (BP).

What were experts saying in the BP era? Here are some examples:

“The masks worn by millions were useless as designed and could not prevent influenza.” –John Barry, The Great Influenza, 2004.

“The use of fabric materials may provide only minimal levels of respiratory protection to a wearer against virus-size submicron aerosol particles (e.g. droplet nuclei). This is partly because fabric materials show only marginal filtration performance against virus-size particles when sealed around the edges. Face seal leakage will further decrease the respiratory protection offered by fabric materials.” –Rengasamy et al.2010. Ann Occup Hyg Oct:45(7):789-98.

“In conclusion, our findings suggest that household contacts of persons with symptomatic virus infection are at risk of infection by multiple modes, and that aerosol transmission is important. This is suggestive of the need for further studies into personal preventative measures for the control of influenza; although our observations suggest that hand hygiene and surgical face masks may not provide high levels of protection against influenza virus transmission in these settings.” –Cowling et al. 2013. Nat. Commun. 4:1935. (Randomized controlled trial analysis).

“We know that wearing a mask outside health care facilities offers little, if any, protection from infection…In many cases, the desire for wide spread masking is a reflexive reaction to anxiety over the pandemic.” –Klompas et al. 2020. NEJM. 382;21.

“We did not find evidence that surgical-type face masks are effective in reducing laboratory-confirmed influenza transmission, either when worn by infected persons (source control) or by persons in the general community to reduce their susceptibility.” – Xiao et al, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 26(5):967-975. (Meta-analysis from 10 randomized controlled trials)

“This study is the first RCT of cloth masks, and the results caution against the use of cloth masks…cloth masks should not be recommended for HCWs, particularly in high-risk situations, and guidelines need to be updated.” MacIntyre et al. 2015. BMJ Open. 5:e006577. (Randomized Controlled Trial)

“Our review of relevant studies indicates that cloth masks will be ineffective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, whether worn as source control or as PPE.” Brosseau and Sietsema, 2020. Center for Infectious Disease Reporting and Prevention (CIDRAP). University of Minnesota.

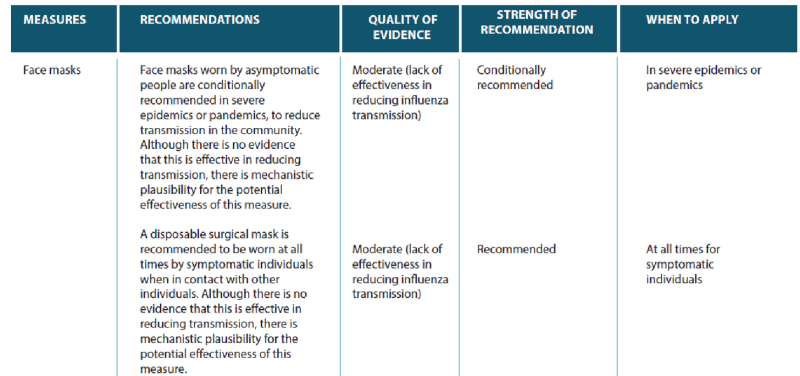

In addition to published papers and articles from PPE experts, pandemic planning documents up until 2020 did not suggest masks would provide significant protection from transmission or infection

Yet, in Feb-March 2020, mask use began to increase among the general public.

Public health officials, including the Surgeon General Jerome Adams, CDC Director Robert Redfield and NIH/NIAID director and presidential advisor Anthony Faucidiscouraged the use of masks for the public. Dr. Adams went as far as to say that improper mask usage could actually increase infections, due to constant touching/adjusting.

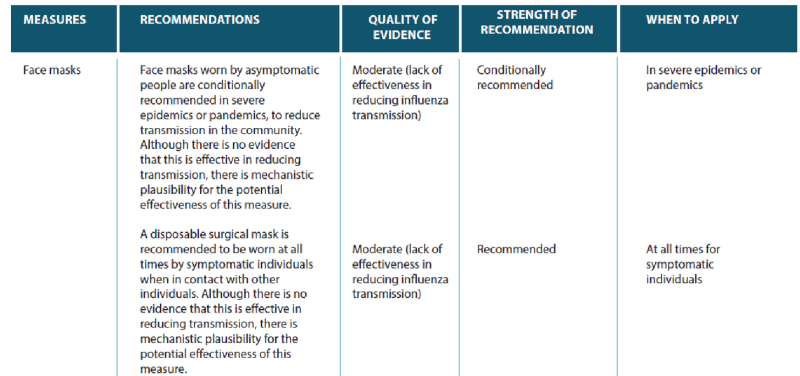

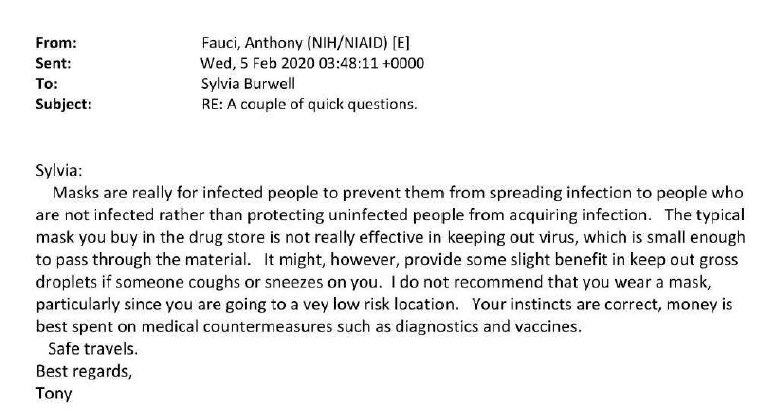

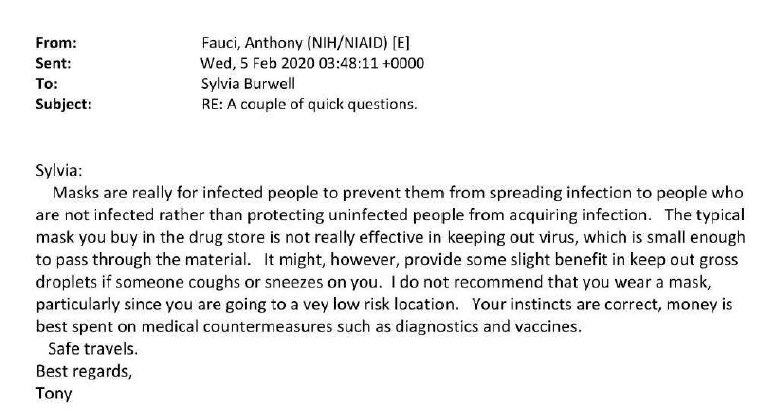

The discouraging of the public to wear masks was explained later as a noble lie to protect PPE supplies for healthcare workers. But what did public health leaders tell close associates in private? NIH/NIAID Director Anthony Fauci’s emails were acquired via the Freedom of Information Act, and it turns out he was saying the same things in private that he was saying in public:

After Things Got Political (AP).

For a short time, there seemed to be a gray area, where experts and others opened the door to the possibility of universal masking, despite a lack of evidence. Here Ben Cowling at Hong Kong University (who I cited above in his groups’ 2013 Nature Communications paper) and colleagues at other universities started to hedge a bit:

“However, there is an essential distinction between absence of evidence and evidence of absence. Evidence that face masks can provide effective protection against respiratory infections in the community is scarce, as acknowledged in recommendations from the UK and Germany. However, face masks are widely used by medical workers as part of droplet precautions when caring for patients with respiratory infections . It would be reasonable to suggest vulnerable individuals avoid crowded areas and use surgical face masks rationally when exposed to high-risk areas. As evidence suggests, COVID-19 could be transmitted before symptom onset, community transmission might be reduced if everyone, including people who have been infected by an asymptomatic and contagious, wear face masks.” – Feng et al.2020. The Lancet. 8:434-436.

As mentioned in the article above, in March-April, 2020, there were numerous reports of asymptomatic spread. Widespread shutdowns threatened to cause incalculable collateral damage. How to reopen became a huge problem for leaders, who needed to reassure a terrified public. “What if the world reopened, and no one came?” David Graham wrote in The Atlantic.

Now we know that asymptomatic transmission is not a major mode of spread, as discussed here and here.

The CDC began recommending masks for the public on April 3, 2020. Their website didn’t cite any evidence for efficacy of masks, only that SARS-CoV-2 is likely transmitted through aerosols, not large droplets. Yet strangely, as I have already mentioned, large droplets were more efficiently stopped by masks in controlled lab studies.

The CDC’s own website didn’t clarify the issue, and their recommendations for the public were contradicted by their recommendations for healthcare wokers. From April to June, 2020, here is what the CDC.gov website advised for healthcare workers:

“Although facemasks are routinely used for the care of patients with common viral respiratory infections, N95 or higher level respirators are routinely recommended for emerging pathogens like SARS CoV-2, which have the potential for transmission via small particles (emphasis mine), the ability to cause severe infections, and no specific treatments or vaccines.”

This information was removed on June 9th, and replaced with more vague language: “Put on NIOSH-approved N95 filtering facepiece respirator or higher (use a facemask if a respirator is not available).”

Opinion pieces written by epidemiologists and physicians calling for universal masking proliferated as fast as the virus:

“As SARS-CoV-2 continues its global spread, it’s possible that one of the pillars of Covid-19 pandemic control — universal facial masking — might help reduce the severity of disease and ensure that a greater proportion of new infections are asymptomatic. If this hypothesis is borne out, universal masking could become a form of “variolation” that would generate immunity and thereby slow the spread of the virus in the United States and elsewhere, as we await a vaccine.” Gandhi M, Rutherford GW. Facial Masking for Covid-19 – Potential for “Variolation” as We Await a Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020. Epub 2020/09/09. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2026913.

Public health officials also piled on the hyperbole about the newly declared panacea of universal masking. CDC director Robert Redfield said that “I might even go so far as to say that this face mask is more guaranteed to protect me against COVID than when I take a COVID vaccine”.

In many opinion pieces pushing universal masking, a single paper by Leung et al was highly cited (see citations at bottom of page in link) as new, conclusive evidence. This paper was from the Cowling group at Hong Kong University, whose views towards universal masking seemed to be evolving rather rapidly.

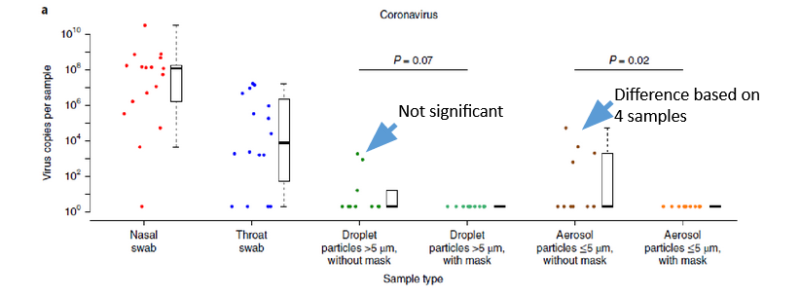

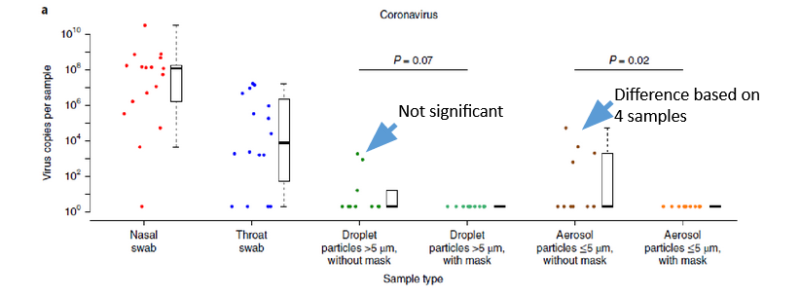

All of the claims in the paper and in subsequent citations regarding the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 by face masks rested on this panel:

On the left side of the panel are the results of RT-PCR amplification tests with nasal and throat swabs. These identified patients as positive for SARS-CoV-2. Yet when masked or unmasked patients breathed into a particle collector, very few had detectable viral RNA (as shown in the right panels). In fact, only three had detectable viral RNA in large droplet particles, while viral RNA was detected in 4 individuals in aerosol-sized droplets (as shown by blue arrows I added). This resulted in only a significant difference in aerosol-sized droplets, and if even one of those patients had been negative, the significance would have likely disappeared. In addition, viral RNA doesn’t equal live virus, so there was no way they could know if what they were detecting in the four patients was actually infectious. To their credit, the authors admitted many of these limitations, yet suggested that “surgical face masks couldprevent transmission of human coronaviruses and influenza viruses from symptomaticindividuals”. No mention of asymptomatic individuals, which was the entire rationale for universal masking.

Another early paper highly cited by the media reported results of a meta-analysis of 29 studies performed by Chu et. al, who “did a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the optimum distance for avoiding person-to person virus transmission and to assess the use of face masks and eye protection to prevent transmission of viruses.” They found that “face mask use could result in a large reduction in risk of infection, with stronger associations with N95 or similar respirators compared with disposable surgical masks or similar.”

This study, too, had some serious limitations. Seven of twenty-nine studies that were included on masking were unpublished and observational, and only two were related to non-healthcare settings. One study actually showed no benefit of face masks, and another relied on retrospective telephone interviews in Beijing about transmission of SARS-CoV-1. This was not the highest quality evidence, and the authors acknowledged that the certainty of their findings was low. Furthermore, meta-analyses are susceptible to significant bias depending on how studies are included and interpreted. Yet despite these limitations, this paper was publicized as conclusiveevidence in support of universal masking.

There were some scientists that pushed back on the emerging narrative of universal masking as an indispensable tool of pandemic mitigation. Here’s Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson, of the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford University:

“The increasing polarised and politicised (sic) views on whether to wear masks in public during the current COVID-19 crisis hides a bitter truth on the state of contemporary research and the value we pose on clinical evidence to guide our decisions……It would appear that despite two decades of pandemic preparedness, there is considerable uncertainty as to the value of wearing masks.”

However, experts that pushed back against universal masking were often reprimanded, and many recantations appeared to soften their previous positions. On July 22, 2020, Dr. Michael Osterholm, Director of CIDRAP at the U. of Minnesota, placed this disclaimer on the CIDRAP website regarding the April 1, 2020 article by Brosseau and Sietsema. “I want to make it very clear that I support the use of cloth face coverings by the general public. I wear one myself on the limited occasions I’m out in public. In areas where face coverings are mandated, I expect the public to follow the mandate and wear them.”

On June 3, 2020, NEJM published this letter to the editor from Klompas et al: “We understand that some people are citing our Perspective article (published on April 1 at NEJM.org) as support for discrediting widespread masking. In truth, the intent of our article was to push for more masking, not less. It is apparent that many people with SARS-CoV-2 infection are asymptomatic or presymptomatic yet highly contagious and that these people account for a substantial fraction of all transmissions. Universal masking helps to prevent such people from spreading virus-laden secretions, whether they recognize that they are infected or not.” To support this statement they cited Leung et al, the paper by the Cowling group that I discussed above, as conclusive evidence that masks were effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, despite its limitations. Read the article yourself and determine if the authors’ intent was to push for more masking.

In June, 2020, MacIntyre et al published a very timely post-hoc study of the 2015 Randomized Controlled Trial (quoted above) that demonstrated increased influenza infections with cloth masks worn by Vietnamese healthcare workers. They stated they were motivated, 5 years after the first study, because “Given the urgency around the safety of cloth masks and the controversy caused by the results of our RCT, we analysed unpublished data on cleaning of the cloth masks and ward allocation from the 2015 trial, as well as unpublished data from a substudy on viral contamination of cloth and medical masks.” They reported that healthcare workers with hospital laundered-masks rendered them as effective as surgical masks, and this simple measure, considered unnecessary to analyze previously, was sufficient to explain the disparate results of the 2015 study.

Then came DANMASK-19: The first randomized controlled trial for public masking during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In this study, “A total of 3030 participants were randomly assigned to the recommendation to wear masks, and 2994 were assigned to control; 4862 completed the study. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 occurred in 42 participants recommended masks (1.8%) and 53 control participants (2.1%)…Althoughthe difference observed was not statistically significant, the 95% CIs are compatible with a 46% reduction to a 23% increase in infection.” Of course, DANMASK-19 had some limitations, with a small number of infections during trial period, antibody tests used to verify 84% of infections, difficulty in determining compliance, no blinding (not possible with participants), and self-reported data.

Yet the political pushback from the study was much more informative than the results of the study itself. First, despite no significant difference between masked and control groups in the study, the authors felt compelled to voice their support for universal masking in the discussion of the paper. Second, as an unusual decision, the journal Annals of Internal Medicine published a critique at the same time as the article authored by Tom Frieden, former CDC director and fierce advocate of universal masking. Third, the chief editor of AIM, Christine Laine, published an apologetic commentary in the same issue, defending the decision to even allow the study to be published.

The New York Times, with obvious pre-publication access to the study results, released an article originally titled “Danish Study Questions Use of Masks to Protect Wearers” that acknowledged the outcome, but also downplayed the effect that the study would have on mask mandates. Yet they changed the headline the very next day, to read “A New Study Questions Whether Masks Protect Wearers. You Need to Wear Them Anyway”.

In contrast the the advocacy journalism of the New York Times, Professor Carl Heneghan’s own analysis of the DANMASK-19 study was flagged as misinformation on Facebook.

Not surprisingly, a CDC study of a limited time period after mask mandates validated its own recommendations, with decreased cases in multiple areas of the U.S. three weeks after implementation of mask mandates. And of course this one had some limitations, too, as the only significant difference was in ages <65, and the study only examined a period of March-October, 2020, and ignored subsequent surges in the fall in many of the areas analyzed.

Interestingly, a similar study by Monica Gandhi and others was retracted, because they didn’t ignore the subsequent surges in the fall. Their retraction letter noted the group will work to publish further work using data on the 2nd and 3rd waves, but these haven’t been forthcoming, almost a full year later.

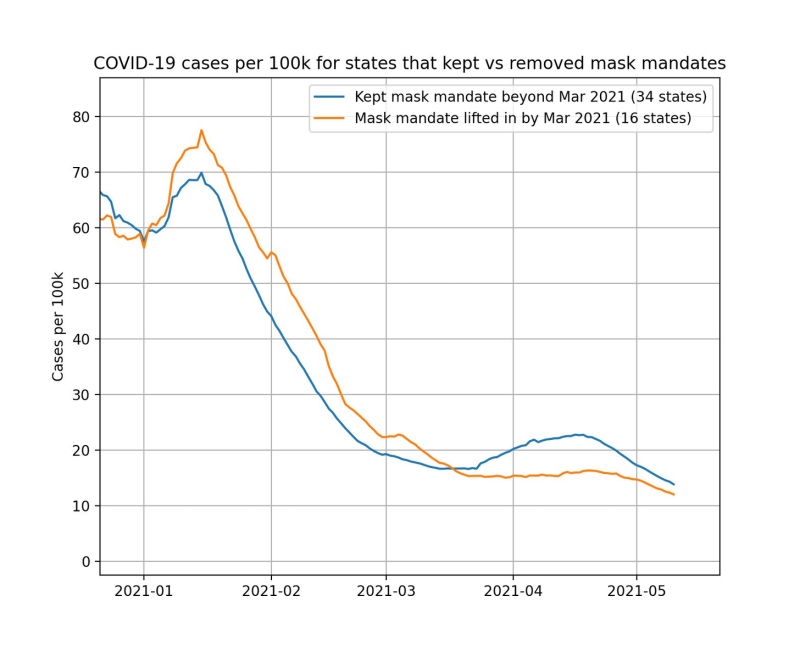

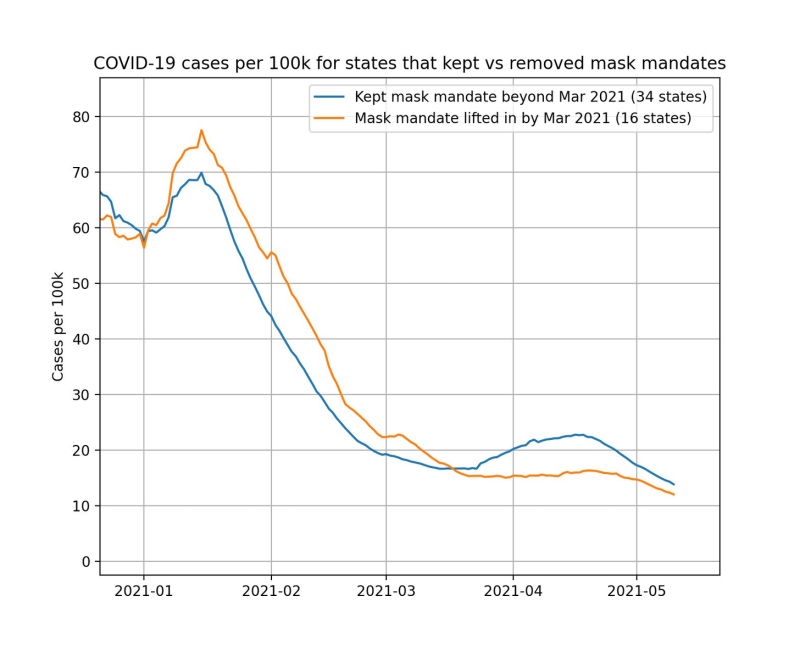

An analysis of the effect of lifting mask mandates was eventually done by independent analyst Youyang Gu, who despite being 26 years old and living with his parents, managed to develop a COVID model more accurate than the IHME. His analysis showed no differences in cases in states where mask mandates were lifted compared to those where they were retained:

The most recently hyped mask study compared villages in Bangladesh that received intensive promotion, instruction, and materials for cloth or surgical masking, compared with villages that did not receive any intervention. This study reported a significant decrease in seropositive individuals, but only in those over 50 and only with surgical masks. The interpretation of this study has some serious limitations, which are well-covered here and here.

First, the researchers used case numbers as a starting point to group villages without knowing testing levels, then used seropositivity as the measured outcome. Second, the researchers really pushed masks on the population, so there’s little way of knowing exactly how this affected reporting, blood sampling, and changes in other behavior, which they noted was affected in masked villages (e.g. more distancing). And it’s unlikely the modest differences observed couldn’t be easily swamped by any number of those possible confounders.

If one actually takes the time to consider the preponderance of evidence regarding universal masking, it becomes extremely difficult to conclude that it has had, or was ever expected to have, a significant effect on the course of the pandemic. The evidence certainly doesn’t come even close to matching the quasi-religious fervor exhibited by the popular media, mask-mandating helicopter politicians, or your judgy virtue-signaling neighbor. And all of the new evidence that supports universal masking should be even more suspect considering the stratospheric bias of the media, public health agencies, politicians, and a terrified public all clamoring for studies that report positive effects, despite their obvious limitations.

In contrast to evidence, it is much more easy to conclude that safety culture politics trampled our understanding of this intervention so completely and at a level previously unknown in our lifetime, that it will take years to sort out its real-world effects. And it doesn’t take a PPE expert to realize that.

Reprinted from the author’s substack.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.