The 2010’s saw the proliferation of laptops, tablets, and all kinds of devices in classrooms. Consumer devices that were originally designed for entertainment or work productivity were repurposed for educational content delivery, digital textbooks, and new “individualized learning.”

Personal computing and internet-connected devices were believed to be an equalizing force that would narrow the gap between the digital haves and have-nots. The decade saw a major change in how students interacted with and used technology. No longer reserved for research in the library, computer class, or sitting at a workstation with a special software program; devices were now everywhere, all the time. A student having ubiquitous access to a world of instant information would usher in a new era of equity and improved education outcomes.

A Brookings Institute paper in 2013 summarized the promise of personal internet devices:

“Mobile learning represents a way to address a number of our educational problems. Devices such as smart phones and tablets enable innovation and help students, teachers, and parents gain access to digital content and personalized assessment vital for a post-industrial world. Mobile devices, used in conjunction with near universal 4G/3G wireless connectivity, are essential tools to improve learning for students.”

In December 2019, mere months before Covid school closures, followed by virtual and hybrid school modes across the US in response to the Covid pandemic, an MIT Technology Review article titled ‘How Classroom Technology is Holding Students Back,’ detailed the alarming results that a years long push that the “device for every child” movement had achieved.

“A study of millions of high school students in the 36 member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that those who used computers heavily at school “do a lot worse in most learning outcomes, even after accounting for social background and student demographics.” According to other studies, college students in the US who used laptops or digital devices in their classes did worse on exams. Eighth graders who took Algebra I online did much worse than those who took the course in person. And fourth graders who used tablets in all or almost all their classes had, on average, reading scores 14 points lower than those who never used them—a differential equivalent to an entire grade level. In some states, the gap was significantly larger.”

The results were damning, and the article’s analysis was sobering.

As for all of the unbounded optimism and confidence that these devices were “essential” (just ask the executive from the tech companies!) the study that the article referenced found:

“…questionable educational assumptions embedded in influential programs, self-interested advocacy by the technology industry, serious threats to student privacy, and a lack of research support.”

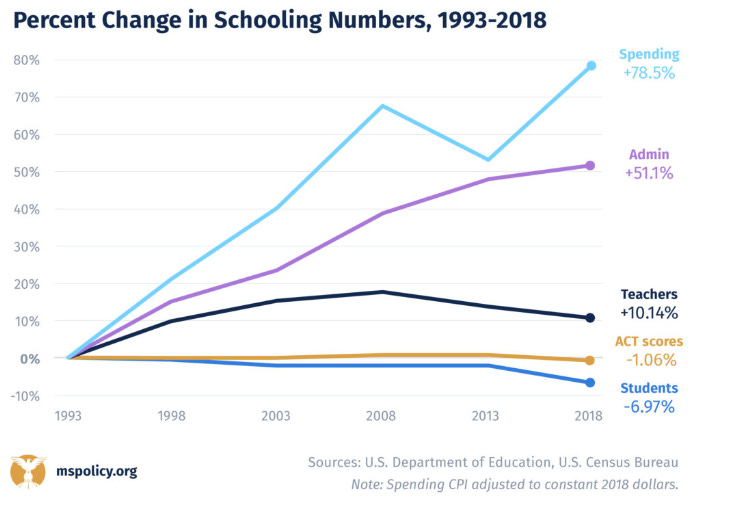

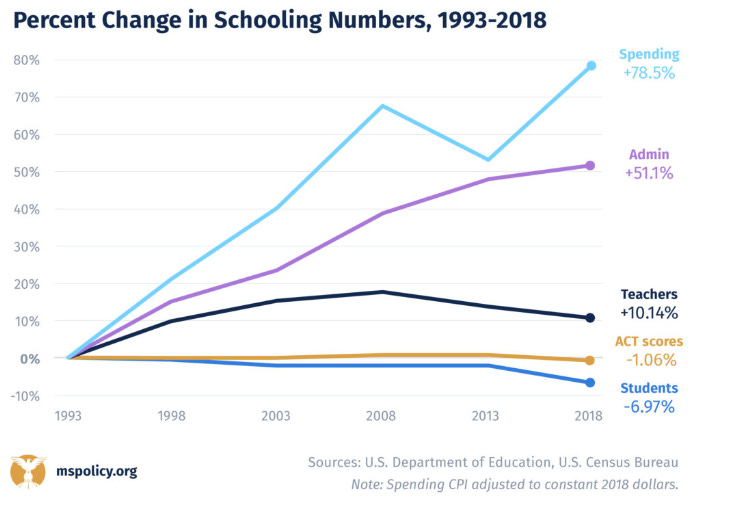

The ever-increasing administrative overhead of educational institutions might be explained partially by this “self-interested advocacy” in the Tech Industry, which has lead to massive increases in spending for adopting their “solutions.”

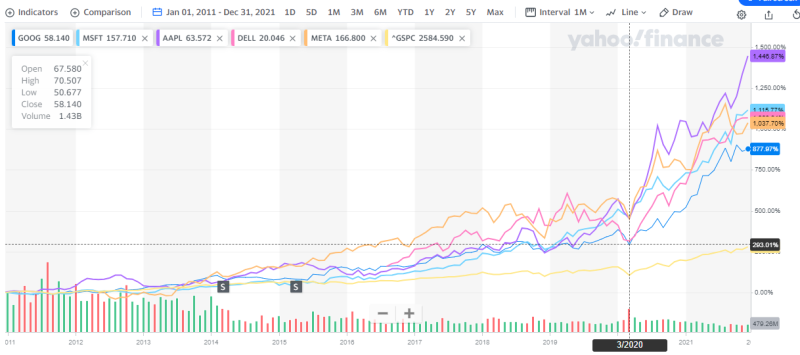

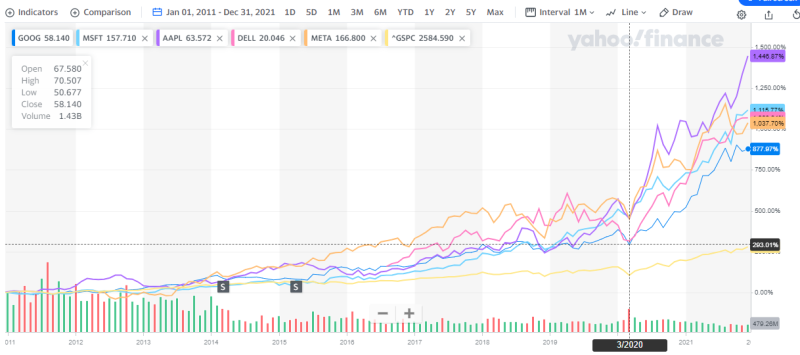

Nowhere was this more evident than during the pandemic, when the major technology companies seized the moment to come to the rescue of school systems and politicians who closed schools. Observe the stock performance for some of the largest tech firms in the nation: March 2020 saw the explosive growth for Google, Microsoft, Apple, and others. (As of this writing, that bubble has since burst).

Observing this sampling of Big Tech Benevolence, one would think that the promises of digitization and a device for every child would usher in a new era of improved outcomes, increased equity, and a narrowing of the “digital divide.” Reading the marketing from the tech firms, one might get the impression that these initiatives were part of their charitable, non-profit efforts.

To be sure, these firms do engage in plenty of charitable work, and donate lots of money and technology to good causes. However, the massive amount of spending that the federal government threw at education from the Cares Act, and other pre-existing funding mechanisms ( in addition to the proliferation of remote work for white collar jobs) contributed a massive portion of these companies’ profits during the pandemic.

Despite the marketing and the absolute certainty that more tech is “vital for a post-industrial world,” and a necessity for achieving educational equity, the results were not so promising. The MIT article addresses that premise directly:

“Judging from the evidence, the most vulnerable students can be harmed the most by a heavy dose of technology—or, at best, not helped. The OECD study found that “technology is of little help in bridging the skills divide between advantaged and disadvantaged students.” In the United States, the test score gap between students who use technology frequently and those who don’t is largest among students from low-income families.”

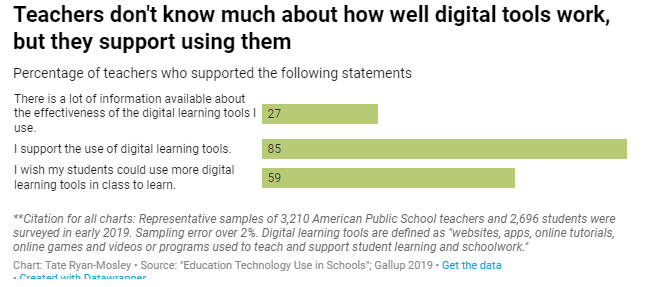

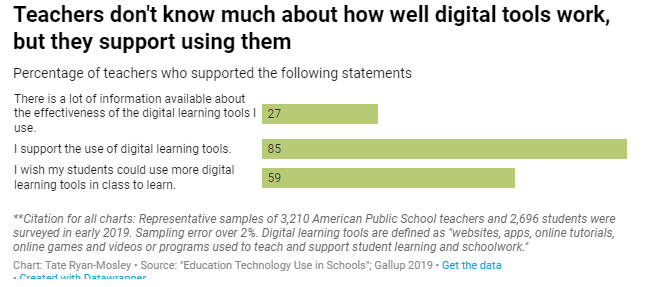

The fundamental belief at the heart of the push for more technologification of classrooms was this: technology, for its own sake – is good. This created a sort of circular reasoning that justified the push for more and more adoption of screens and digitization of all content, for no other reason than to be able to deliver it digitally. As you can see from this survey result, it was supported widely, yet few really had any idea about its effectiveness.

The concern about students entering the workforce unprepared for the increasingly tech-ified workplace was logical. Who can blame anyone for wanting to prepare kids to get jobs that would increasingly rely upon the same technology they were implementing in the classrooms? If tech can even help in some way to level the playing field, then it’s worth a shot. No one can blame anyone for thinking this way. Few were on the opposing side of increasing tech adoption.

How did we get here?

As a society, we have been replacing menial, slow tasks that used to take our precious time, with automated, immediate, digital counterparts . Remember when you couldn’t text your spouse from the grocery store if you forgot what you were supposed to get? Remember having to flip through a phone book to look for a plumber?

These represent just a few of the many ways that mobile internet-connected devices have improved our lives by shaving off precious seconds of our day, freeing them up for other things. This is great for situations where those tasks do not add value nor are particularly enjoyable. These digital shortcuts we employ in our daily lives are supposed to improve our quality of life, and perhaps they do.

These shortcuts are the result of the digitization of processes: analog, manual, and slow. Now: repeatable, fast, and mindless. In the digitization process, they also take something away. They are a substitute for figuring things out on our own. Thinking through complexity. Removing the process of the mind laboring, exercising, actually thinking, counteracts the process of learning. The learning process requires stress, mental trial and error, and time. All three of those things that technology removes.

It should be no surprise then that the results of the digital revolution in education were a massive disappointment.

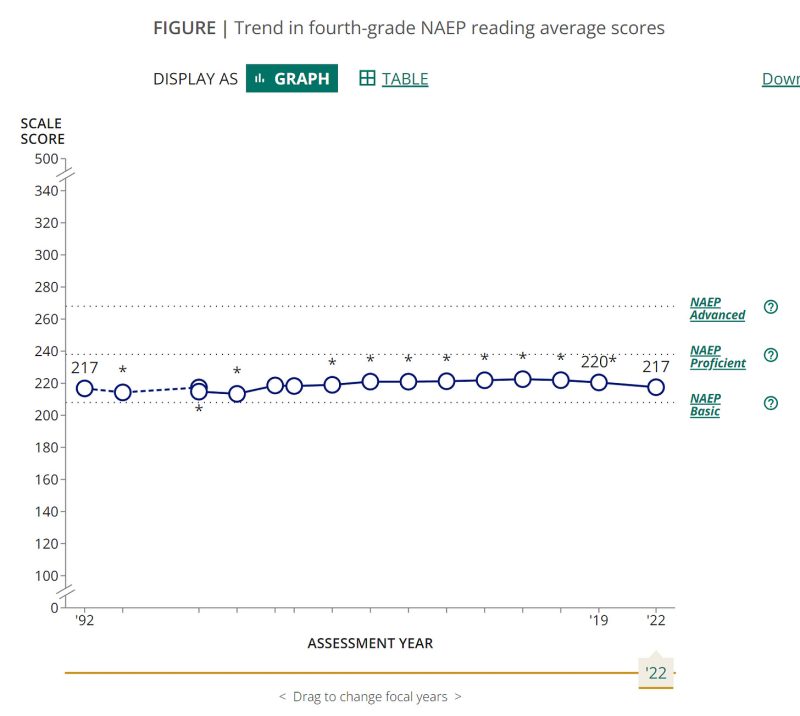

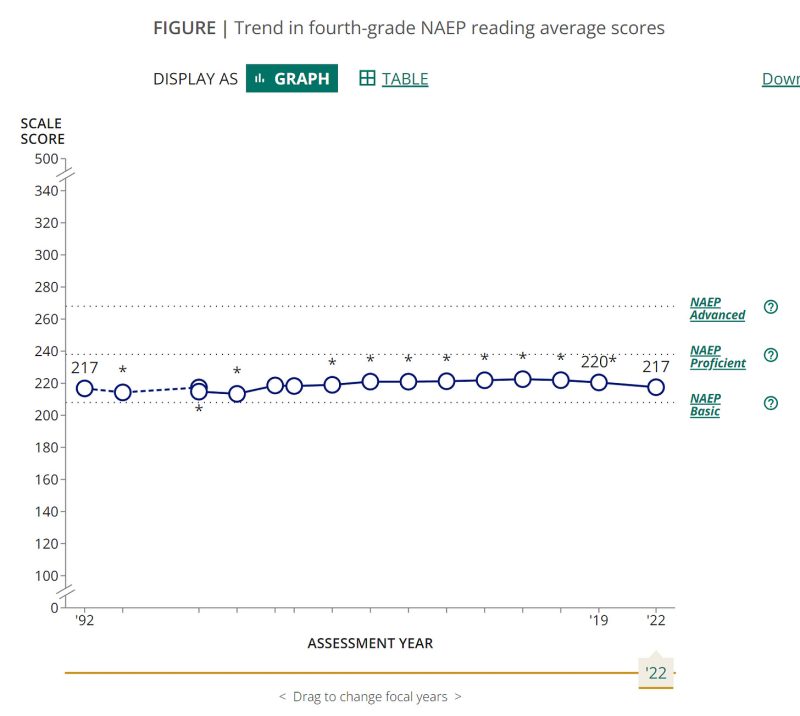

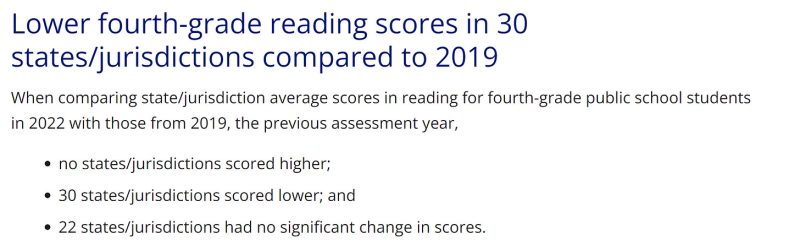

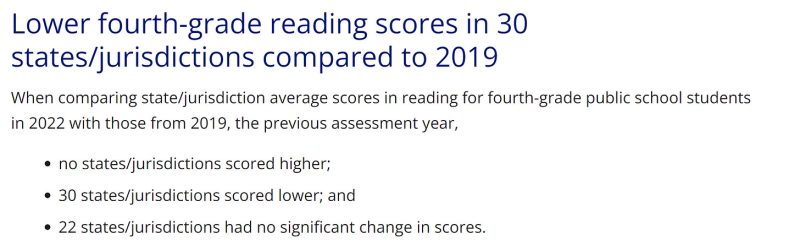

The Nation’s Report Card: Trend in 4th Grade reading average scores.

Where are we now?

Fast forward from 2019, to 3+ years later where our children have all experienced up to 1 1/2 years of fully remote or hybrid “learning” – delivered exclusively through screens. Every parent who has had to experience the frustration of their children doing “Zoom School” – and the utter disaster that was remote learning needs no convincing that technology was no magic bullet for education. While certainly offering specific advantages for certain subjects, and conveniences in specific contexts, it’s now abundantly clear that more tech ≠ more learning.

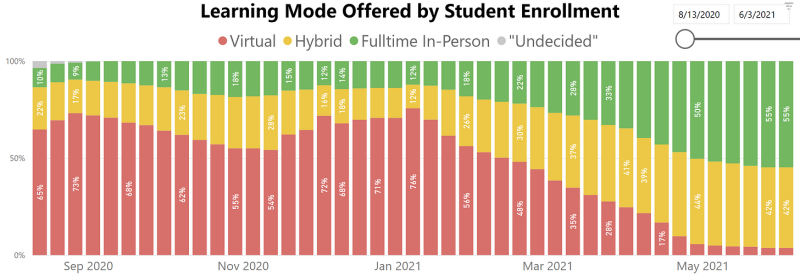

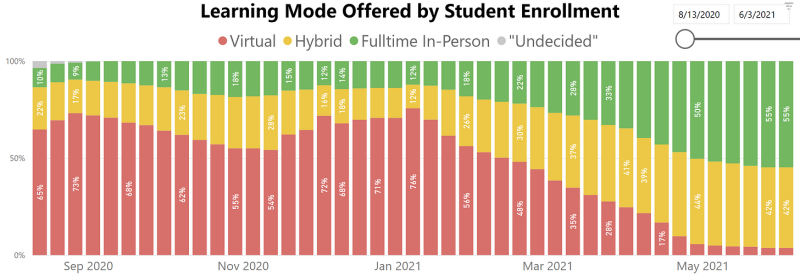

School Learning Mode by Student Enrollment: 2020/21 School Year

Source: Burbio.com

A more recent article in the same publication reflects an accurate picture of our current reality. Kids are surrounded by screens. They are reading text from all sorts of devices and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. The article balances that reality with reserved optimism about the current innovations in educational technology. Yet the fact remains that in 2023, two-thirds of American school children cannot read at grade level.

The results we were promised from increased tech adoption, always available learning content, and a device for every child has turned out to be not much more than a successful marketing campaign. One where tech corporations cashed in, government overspent taxpayer money, and once again, the children were let down.

Reposted from the author’s Substack

References:

https://time.com/6266311/chatgpt-tech-schools/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11528-021-00599-4

https://www.usaspending.gov/disaster/covid-19?publicLaw=all

https://mspolicy.org/public-education-spending-and-admin-staff-up-enrollment-down-outcomes-flat/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11528-021-00599-4

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.