[Jason Onke is guest co-author on this piece]

The Infection Fatality Ratio (IFR) estimates the percentage deaths in all those with an infection: the detected (cases) and those with undetected disease (asymptomatic and the not-tested group).

The IFR is used to model the estimated number of deaths in the population at large. If it’s a large number approaching one percent, then the modelled outputs can report an alarming number of fatalities – providing the impetus for lockdowns.

Early in the pandemic, Imperial College London’s Report 9 modelled the impact of covid based on a publication by Verity et al. on 13 March 2020, which estimated the IFR as 0.9 percent.

This IFR gave rise to the modelled estimates ‘in an unmitigated epidemic, we would predict approximately 510,000 deaths in GB and 2.2 million in the US.’

The authors wrote this: “However, the resulting mitigated epidemic would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over. For countries able to achieve it, this leaves suppression as the preferred policy option.”

A recent publication by Stanford researchers based on seroprevalence studies in the covid pre-vaccination era provides a more robust estimate of the IFR.

Across 32 studies, the median IFR of COVID-19 was estimated to be 0.035% for people aged 0-59 years and 0.095% for those aged 0-69.

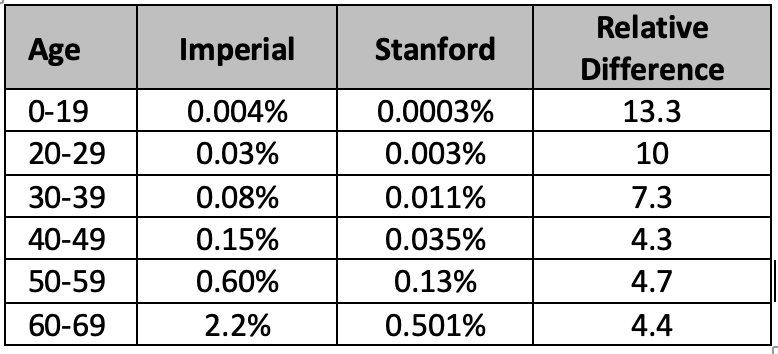

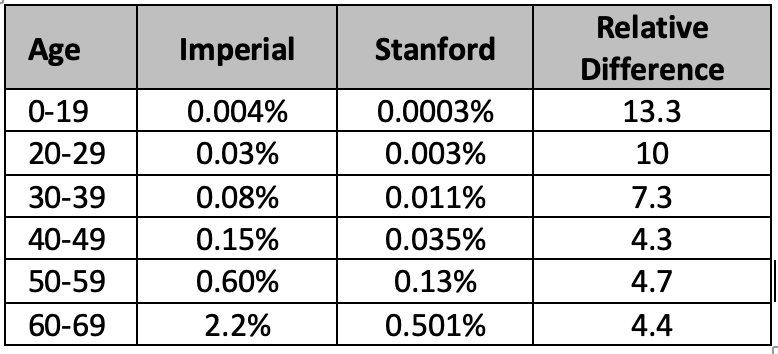

We compared the two IFR estimates, which shows the Imperial College estimates are much higher than Stanford’s across the age groups.

Estimating IFR in the early stage of outbreaks is so error-prone that it should come with a warning. Antibody studies provide a more accurate understanding of how many people have been infected and permit a more precise estimate of the IFR. However, early in the pandemic, such studies are not available—Verity et al. based their IFR on Chinese data and just 1,334 cases outside mainland China. The case fatality ratio was estimated on just one severe case in those under 19s.

Instead of early models and predictions, an alternative strategy is to analyse the data as it emerges: work out what is going on. We did this, and by April 2020, we wrote that it was increasingly clear that the ‘age affected structure doesn’t fit with pandemic theory.’

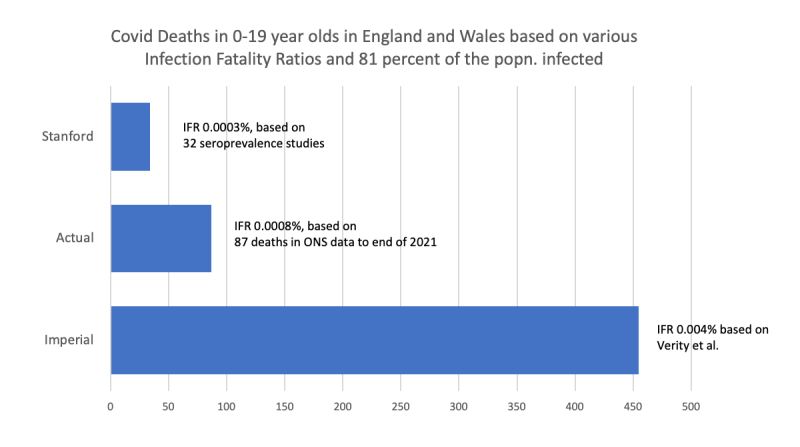

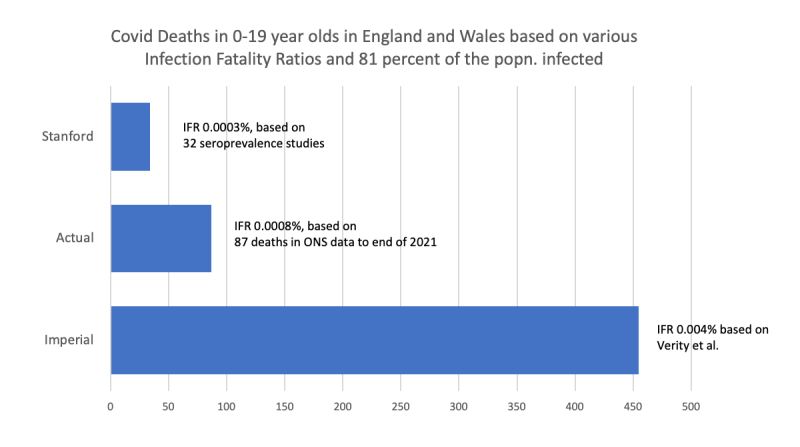

The early IFR estimates frrom Imperial College were substantially overestimated across the ages compared to Stanford’s seroprevalence studies – more than ten-fold in those under 19. But how does it compare with the actual data?

Imperial College predicted that 81% of the GB population would be infected throughout the epidemic. By 31 December 2021, the ONS infection survey estimated that 81% of England’s population had COVID-19. ONS reports 87 registered deaths in 0 to 19-year-olds in England and Wales by this date.

We used these data to back-calculate the IFR in the 0-19-year-olds based on 11.36 million (81% of the population) in this age group infected by the end of 2021. This gave an IFR estimate of 0.0008% (see figure).

The consequences of overestimating the IFR are profound. It overpredicts the number of deaths and influences political decision-making without considering the long-term harm and well-being effects.

Overestimating the IFR is not that unusual. For example, in the Swine flu pandemic, the post-pandemic IFR was reported as 0.02%, fivefold less than the lowest estimate during the outbreak.

There are further problems with the IFR to consider. First, it assumes all deaths with a PCR-positive test or covid on the death certificate were caused by SARS-CoV-2. This Is not the case, as we have shown. The IFR also doesn’t account for hospital deaths or the complex interaction of multimorbidity and the assignment of causation.

An analysis distinguishing causation in under 18s, as opposed to those who died of another cause but were coincidentally infected, reported a mortality rate in < 18-year-olds of two per million—suggesting an IFR of 0.0002%, and covid is possibly the underlying cause of death in only about a quarter of young people when it is registered on the death certificate.

Invoking the precautionary principle for the widespread use of restrictions based on catastrophic predictions also underlines the misunderstanding of the basis of the principle: act only when you are sure that the benefits of your actions outweigh the negative consequences. No such evidence existed then, as lockdowns were not even contemplated in the existing pandemic plans.

Reposted from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.