The Supreme Court recently hearing arguments in the case of Murthy v. Missouri has refocused attention on the US government’s efforts to get social media platforms to suppress alleged Covid-19 “misinformation” and the issue of whether these efforts crossed the “line between persuasion and coercion” and thus constituted government censorship.

But how could the government’s efforts have not constituted government censorship when it had a full-fledged “Fighting Covid-19 Disinformation Monitoring Programme” in which all the major online platforms were enrolled and which required them to submit periodic reports outlining, even indeed quantifying, their suppression of what was deemed “false and/or misleading information likely to cause physical harm or impair public health policies?”

The programme covered almost the entire official course of the declared Covid-19 pandemic. It was rolled out in early June 2020, just three months after the WHO’s pandemic declaration, and it was only wound up in summer 2022, after most of the measures adopted in response to the pandemic declaration, including various forms of vaccine passports, had already been withdrawn. The participants in the programme included Twitter, Facebook/Meta, Google/YouTube, and Microsoft (as owner of Bing and LinkedIn). An archive of the no less than 17 reports which each of them submitted to the government can be seen below.

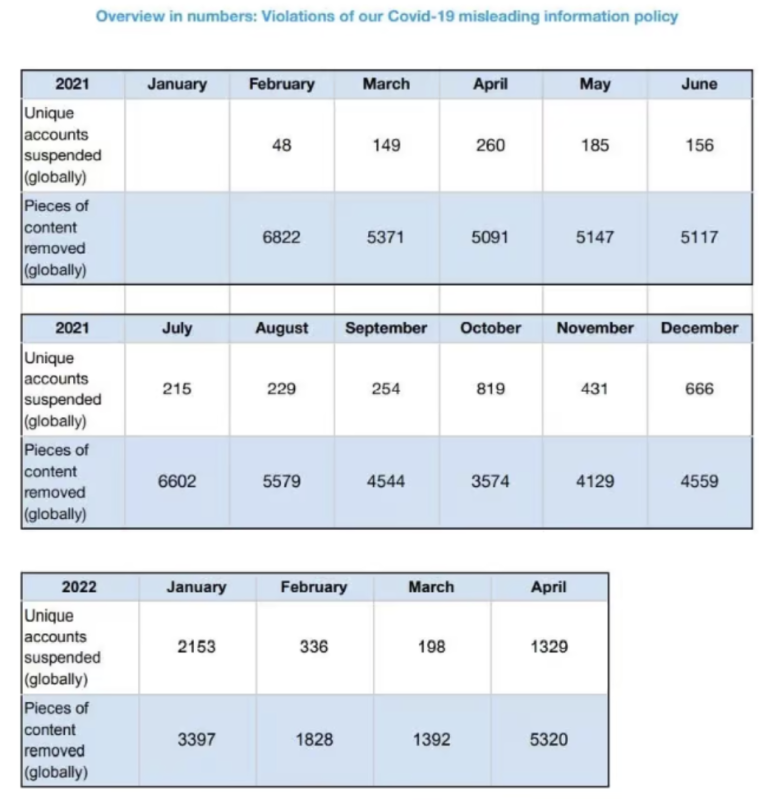

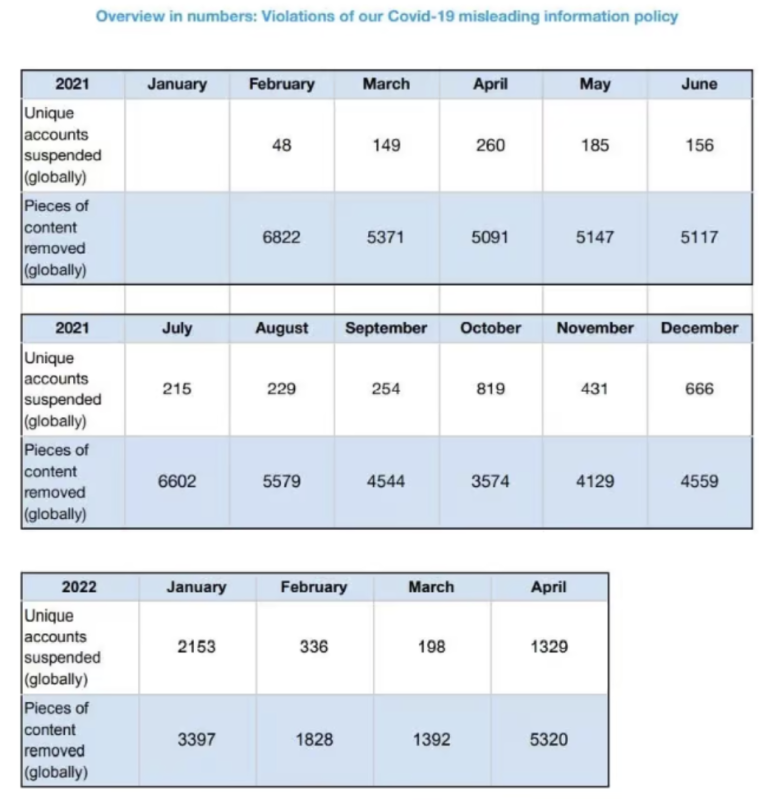

A presentation of the data submitted specifically by Twitter in its final report can be seen below. Note that the figures given on accounts suspended and pieces of content removed are global figures, i.e. the government censorship programme was affecting Twitter users all around the world.

Moreover, the government had already hit several of the participants in the programme (Google, Facebook, and Microsoft) with massive fines in antitrust cases in recent years, and the programme was being rolled out in conjunction with draft legislation which was practically guaranteed to become law and which gave the government the following powers, among others:

- The power to fine platforms up to 6% of their global turnover if they fail to comply with the government’s censorship demands: i.e. to suppress what the government deems misinformation or disinformation.

- The power to conduct “dawn raids” in case of suspected non-compliance: i.e. to have government agents break into and seal off company premises, inspect books or records in whatever form, and take away copies of or extracts from whatever books or records they deem relevant to their investigation.

- The all-important power, in the context of digital means of communication, to require platforms to provide the government access to their algorithms. This gives the government the opportunity not only to demand open and direct censorship in the form of content removal and account suspension, but also to demand and to influence the more subtle and insidious censorship that takes the form of algorithmic suppression.

In July 2022, the legislation was passed, as expected, and it is now law.

You do not remember this happening? Well, that is not because it did not happen. It did happen. It is because the government in question is not the United States government, but rather the European Commission.

The archive of the Fighting Covid-19 Disinformation Monitoring Programme is here, the cited Twitter report is here, the legislation and now law is the EU’s Digital Services Act, which can be consulted here.

It was thus the European Commission which was the driving force behind the wave of censorship which struck Covid-19 dissent from 2020 to 2022, certainly not the Biden administration, whose role was limited to making informal, essentially toothless requests. There was indeed coercion, there was indeed a threat. But it was coming from a different source: it was the looming threat of the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA).

It should be recalled that in Murthy v. Missouri, the US government has argued that it was merely asking platforms to apply their own content moderation policies. So, the question is: Where did those policies come from? “Content moderation” is, after all, just a kinder, gentler euphemism for censorship. Why should the platforms even have “content moderation” policies? Why do they have them?

The answer is that they have them because the European Union has demanded that they have them: first in the context of suppressing “hate speech” and more recently in that of suppressing alleged “disinformation.” The European Commission launched its so-called Code of Practice on Disinformation in 2018, “voluntarily” enrolling all of the major online social media platforms and search engines into it. Was Google, for instance, which the European Commission had just hit with a record-breaking €4.3 billion fine – plus a €2.4 billion fine just the year before! – going to refuse to play ball? Of course not.

The Fighting Covid-19 Disinformation Monitoring Programme was a sub-programme of the Code of Practice. The Code of Practice would in turn lose its ostensibly “voluntary” character with the passage of the Digital Services Act, as the below European Commission tweet makes perfectly clear.

What is at issue in Murthy v. Missouri is an injunction preventing the US government from communicating with online platforms about “content moderation.” In the meanwhile, however, all the online platforms which signed up to the Code of Practice – and even many which did not but were simply unilaterally designated by the European Commission – have necessarily to be in contact with the latter on their “content moderation” in order to ensure compliance with the Digital Services Act.

The platforms are indeed required to submit periodic reports to the Commission. The Commission is even given the power to demand that the platforms undertake special “content moderation” measures in times of crisis, with a “crisis” being defined as “extraordinary circumstances…that can lead to a serious threat to public security or public health” (preamble, para. 91). Sound familiar?

The 2022 “strengthened” Code of Practice even set up a “Permanent Task Force on Disinformation,” in which representatives of the platforms meet with EU officials at least every six months, as well as in sub-groups in between the plenary sessions. The Task Force is chaired by the European Commission and also, for some reason, includes a representative of the EU foreign service.

So, even supposing the Supreme Court finds in favour of the plaintiffs in Murthy v. Missouri and upholds the injunction, what will have been gained? The US government will be prevented from talking to the platforms on “content moderation,” but the European Commission, the executive organ of a foreign power, will still be able to do so.

How is that a victory? The European Commission is in fact doing so, systematically and in a formalized manner, because the EU’s Digital Services Act makes it nothing less than the arbiter of what counts as “misinformation” or “disinformation” – the very arbiter of truth and falsity – and the platforms have to satisfy the Commission that they are respecting its judgment in this regard or face the ruinous DSA fines.

The fact of the matter is that Americans’ 1st Amendment rights are already well and truly dead and they are dead because of the actions of a foreign power. Lawsuits targeting the US government will do nothing to change this.

Here is what would: for the US Congress to pass its own law making it a crime for US companies to collaborate with a foreign government in restricting Americans’ speech.

The law could give federal authorities the same draconian powers that the DSA gives the European Commission, but now in the cause of protecting speech rather than suppressing it: (a) the power to apply crippling fines for non-compliance; (b) search-and-seizure powers, so that we can know exactly what communications the companies are having with the European Commission or other foreign powers or governments, rather than having to wait, say, for Elon Musk to kindly divulge them at his discretion; (c) the power to demand access to platform algorithms, so that we can know exactly what and whose speech platforms are surreptitiously, algorithmically suppressing and what and whose speech they are surreptitiously, algorithmically amplifying (which is just the flip side of the same coin).

If the platforms want to stay on both markets, then it would be up to them to find a modus vivendi which allows them to do so: for instance, by geo-blocking content in the EU. Censoring Americans’ speech to meet EU demands would no longer be an option.

Jay Bhattacharya, Martin Kulldorff, Adam Kheriarty (all three plaintiffs in Murthy v. Missouri): Are you going to call for such a law?

Senator Ron Johnson, Senator Rand Paul, Representative Thomas Massie: Are you prepared to propose it?

If you truly want to defend Americans’ freedom of speech, then the EU has to be confronted. Attacking the Biden administration for informal contacts with online platforms while staying silent about the EU’s systematic infringement and undermining of Americans’ 1st Amendment rights – and instrumentalizing of American companies to this end! – is not defending freedom of speech. It is grandstanding.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.