In a world where ‘equity’ is the catch-cry of corporatists accumulating unprecedented wealth, the return of colonialism should not surprise. Colonialism, after all, brings great benefits to those whom it disempowers and pillages. Success requires a highly centralized approach to achieve mass control, restricting freedom ‘for the greater good’ whilst silencing those who disagree.

With the World Health Organization (WHO) now rebooted to promote just such approaches, and its calamitous Covid response having recently pushed former colonies further into penury, the stage is set for a return of the old order. An army of international health bureaucrats, equipping themselves with an array of rhetoric around ‘infodemics,’ ‘vaccine equity,’ and a new-found love of corporate sponsorship, are forming the vanguard. The winners, the losers, and the enablers – all the stuff we naively thought we had put aside but was just festering in the shadows.

While European colonialism proved an excellent way to extract the wealth of others, it also had its downsides. One was the inadvertent extraction of pestilence such as cholera and typhus. While smallpox had been a devastating European export, clearing coveted lands for colonial settlement, transmission of disease in the reverse direction upset the colonizers; local laws and expectations applied and mass death and suffering could not be hidden from the public eye.

To address this problem, 12 European countries met in 1851 for the first international sanitary conference. Most were heavily invested in the colonial enterprise, settling and pillaging other lands to demonstrate a higher form of civilization. Some were still actively enslaving people to make this greater good even cheaper to impose. Thus, the noble field of international public health (nowadays rebranded as ‘Global Health’) was born. Regular rebranding is important as the past becomes awkward.

A series of such conferences culminated in the first Sanitary Convention in 1892, and the establishment of the permanent Office Internationale d’Hygiene Publique in Paris in 1907. The countries of the Americas had got in first with their own International Sanitary Bureau in 1902, but the world’s center of gravity was still in Europe. While the great public-private partnerships that had exploited the colonial populations, such as the East India companies, had mostly dissolved, colonial governments were still able to starve and abuse the locals without too much reference to the norms of behavior expected at home. International public health was about keeping the home populations safe, not about dealing with the disease burdens of the colonized.

Colonies could be run with the efficiency of private industry free from the growing expectations of health and welfare in Europe. They were sufficiently distant and profitable for the benefits of extracted wealth to temper any feelings of guilt that such abuse might arouse. The extremes of some late-comers such as systemic mutilation could also serve as outlets for those who wished to vent virtue; this could allow feelings of philanthropic altruism or ‘White Man’s Burden’ to veil the more routine carnage of the more established powers.

Throughout this, the tropical public health schools of Europe helped keep populations productive and profitable whilst reinforcing this veil of benevolence; dictated healthcare to support the corporate-authoritarian state. They also boosted the egos and sense of adventure of the young health professionals the state recruited. There is not much new under the sun.

Between the two world wars colonialism remained good business. The League of Nations trialed inclusiveness by adding the rising Asian colonial power, Japan. The pre-antibiotic Spanish flu had recently wreaked havoc globally with 25 to 50 million deaths between 1918 and 1920, and typhus had continued a deadly path through the First World War. International collaboration made sense, but it would be on the terms of the wealthy and remain primarily focused on threats to their own health.

This elitist view extended to the eugenics movement of the time. Supported by much of the Western public health establishment, this came to be expressed most clearly through their enthusiastic embrace of Nazism in Germany. We usually view Nazism as gray images of jackboots and concentration camps, but this is a distortion; a figment of monochrome film and propaganda. It was considered progressive at the time; people working together in the sun for the benefit of the many, growing prosperity and opportunity.

It captured the minds and hearts of students and the young, giving them a cause to stand for, sanctioning their right to denigrate deviants, non-conformers, and those considered unhealthy or a threat to social purity. As today, this was all promoted from above by a mix of politicians and corporatists and reflected in the professional societies and colleges. It enables people to view the subjugation of others as virtuous. Fascism and colonialism are faces of the same coin.

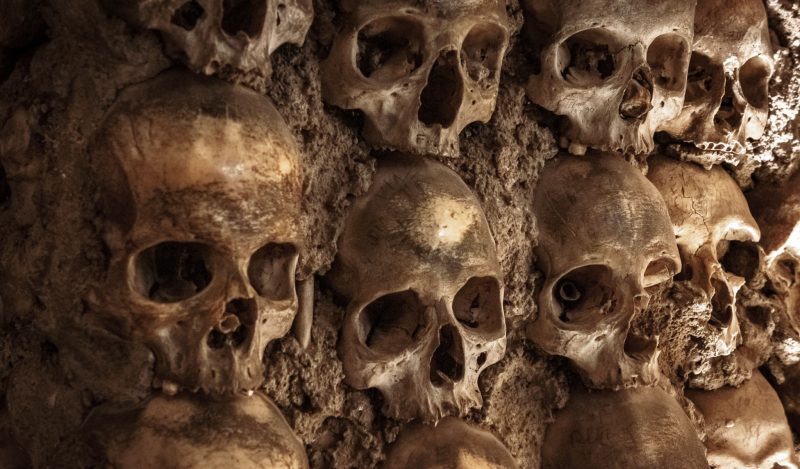

The consequent rotting piled corpses of the death trains of the 1940s, and the mutilated skeletal ghosts of the camps they served, gave medical authoritarianism a bad name. The Second World War also gave colonized populations a path and a means to throw off their oppressors. There followed a few decades in which public health did penance. Career paths required acknowledgement of anti-fascist concepts such as equality between countries, community control of health policy, and the ever-unpopular idea of ‘informed consent.’ Declarations from Nuremberg to Helsinki to Alma Ata promoted this theme, with human rights trending in the media.

For corporate authoritarianism and the colonialist ideal to be made friendly again, the former themes would have to be sanitized. ‘Greater good’ is a good place to start; “Protect your community, get your jab” makes forced compliance sound caring. “No one is safe, until everyone is safe” justifies the demonization of non-compliers. A few generations of forgetting, a bit of rebranding, and it all becomes mainstream again.

Let us dig further into our enlightened present. We pull down the statues of the tyrants, ban the books of racists, then close the markets and schools across low-income countries and expand their debt, ensuring they remain subservient. In wealthy countries, corporatists fund the colleges that train the cadres who then save the ignorant and needy in ‘backward’ States. They arrange for the children to be injected with the medicines the corporatists make, proven effective by the modelers they sponsor and approved by the regulatory agencies they support. The big new public-private partnerships ensure private profit can be driven by public money.

An ever-growing bureaucracy, in an ever-growing list of international agencies, now implements the centrist agenda, removing remaining vestiges of local ownership and control. Thousands of well-salaried ‘humanitarian’ workers are the new East India Company bureaucrats, projecting the same façade of Western largesse to the distant, ignorant, and undeveloped. Untouchable international agencies such as the WHO, external to national judicial control, do the leg work for those with money and power. Two decades ago, emphasis was on empowering communities. I have sat in meetings in recent years where these same people shamelessly discuss defunding countries that don’t comply with emerging Western cultural norms. Cultural imperialism has become acceptable again.

With the world turning full circle, post-World War Two concepts of human rights, equality, and local agency are exiting the international stage. The veiled colonialism currently dressed up as vaccine equity looks like a bunch of colonial bureaucrats forcing their sponsors’ wares on those with less power, whilst building policies to ensure this imbalance remains. Malnutrition, infectious disease, child marriage, and generational poverty are side issues to the East India Pharma and Software Company’s bottom lines. This will stop when those being colonized once again unite and refuse to comply. In the meantime, the enablers could open their eyes and understand who they are working for.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.