“We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.”

-C.S. Lewis “Men Without Chests”

I recently returned from Spain where I participated in a seminar on The Defeat of the West, the most recent book by the well-known French historian Emmanuel Todd. Whether one agrees with all, part, or none of his thesis—I find myself in the second category—it is a compelling and suggestive read, one that in typical Todd style relies on the innovative mixing of demographic, anthropological, religious, and sociological theories to make its case.

One would think that here in what we are constantly told is the beating heart of the West, a book such as this, written by someone who is widely acknowledged to be one of the more prestigious historians and public intellectuals in Europe and who, moreover, sports a very enviable record of prognostication (he was one of the first important public figures to predict the collapse of the Soviet Union), would be the subject of lively speculation on these shores.

But as of yesterday this book, unlike so many of his others, was still unavailable in English, nearly a year after its publication. And outside of a brief article at Jacobin and another by the thankfully iconoclastic Christopher Caldwell at the New York Times, it has garnered no sustained attention within the chattering classes of the US left or right, a fate that would only seem to confirm one of the many excellent points he makes in the book: that one of the more salient features of societies that have started on a sharp descent into cultural decline is their enormous capacity to deny palpable realities.

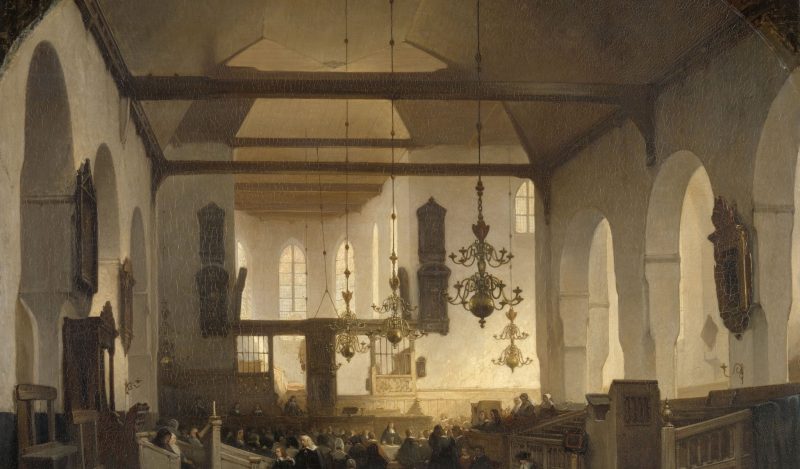

For Todd, decline is inexorably linked with cultural nihilism, by which he means a state of being defined by the generalized absence of consensually recognized moral and ethical structures within the society. Like Weber before him, he sees the rise of Protestantism, with its theretofore largely unknown emphasis on personal responsibility and probity in both personal and public matters, as key to the rise of the West. And he thus sees the final expiration of this same ethos among us, and especially among our elite classes, as heralding the end of our time of unchallenged world prominence.

One can accept or not that it was the particular attributes of the Protestant mindset that, more than anything else, launched the West on its now 500-year reign of world hegemony.

But I think it is harder to dispute his larger and what I think will be his more enduring point: that no society can impel itself toward the commission of great, creative, and hopefully humane things without a broadly agreed upon set of positive moral imperatives emanating from a purportedly transcendent font of power and energy.

Put in a slightly different way, without a set of social norms modeled by our elite classes that encourage us to feel wonder and awe before the condition of being alive, and the sense of reverence that inevitably follows in their wake, human beings will inevitably redound to their most base impulses, something that in turn sets off endless rounds of infighting within the culture, and from there, its eventual collapse.

After saying that, I could, if I wanted to play to the cheap seats, go on a long diatribe about how, over the last 12 or so years, the Democrats, with their many accomplices in the media, academia, and the Deep State have set out quite consciously to destroy this preternatural human impulse toward reverence and all that flows from it, doing so especially, and most criminally, in social spaces inhabited by the young. And no element of that would-be diatribe would be false or misleading.

But in doing so, I’d be engaging in the type of lying and self-deception that these misnamed liberals, with whom I used to mostly identify, are so good at.

The fact is that these so-called progressives were and still are working on well-fertilized terrain, land carefully tilled by Republicans in the wake of September 11th with the plow of fear, the hoe of social ostracism and, above all, the stinking manure of conversation-ending false binaries in our civic discussions. You know, exchanges like this.

Person 1: “I’m troubled by the idea of destroying Iraq, thereby killing and displacing millions, when Saddam had nothing to do with Bin-Laden or September 11th”.

Person 2: “Oh, so you’re one of those America-hating types that loves terrorists and wants to let them kill us all.”

Or things like the brutal cancelling of people like Susan Sontag and Phil Donahue, just to name two, who dared question the wisdom of purposely destroying a country that had had nothing to do with the attack on the Twin Towers.

The conceptual thinking of human beings is largely delimited by the repertoire of verbal devices at their disposal. With more words and tropes come more concepts. With more concepts comes more imagination. Conversely, the fewer available words and concepts a person has, the less rich his repertoire of concepts and imaginative capabilities.

Those who control our media on behalf of the super-elites are well aware of this reality. They knew, for example, that it was perfectly possible to be against what was done on September 11th and not be in any way in favor of the ideas and methods of bin Laden or the goal of punishing Iraq for his sins.

But they also knew that allowing space for this concept in our verbal economy would greatly complicate their preconceived plan to remake the Middle East at the point of a gun. So, they used all the coercive powers at their disposal to disappear this mental possibility from our public life, purposefully impoverishing our public discourse to achieve their private ends. And, for the most part, it worked, paving the way for the use of the exact same techniques, only more widely and more viciously, during the Covid operation.

Americans are a famously transactional people. And we have just elected a famously transactional President. I have nothing against transactional approaches to problem-solving per se. In fact, in the realm of foreign policy, I believe they can often be quite useful. And I believe that if Trump can do away with so many of the ideological a prioris that currently fog American elite thinking on its dealings with the world—including their need to see ourselves as inherently different and better than all other collectives on the earth—he will be doing us and all the world a great favor.

There is, however, one great drawback with transactionalism as it relates to the issue of establishing or re-establishing what I earlier described as “a broadly agreed upon set of moral imperatives emanating from a purportedly transcendent font of power and energy.” And it’s a big one.

Transactionalism is by definition the art of manipulating what recognizably is, and is thus often indifferent when not openly hostile to the process of what we might need or want to be from a moral and ethical point of view down the road.

Am I saying that Trump has no positive vision for the future of the US? No. What I am suggesting, however, is that his vision for the future appears to be rather delimited, and riven, moreover, with contradictions that may sink it in the longer run.

From what I can tell, his outlook revolves around two major positive concepts (amidst a sea of others designed, for better or worse to undo the work of his predecessors (e.g. close up the border). They are a return to material prosperity and a renewed respect for the military, the police, and all other uniformed civil servants. A third, more vaguely and more confusingly expressed positive concept is that of transforming the US from an instigator of wars into a purveyor of peace.

Returning material prosperity is of course a noble goal that if accomplished would alleviate a lot of citizen anxiety and misery. But it does not, in and of itself, address the problem of cultural nihilism that Todd sees as lying at the core of the West’s and hence the US’s social decline. In fact, a good case could be made that by renewing our obsession with the pursuit of material gains at the expense of more transcendently conceived goals, we could, in fact, be unwittingly hastening our descent down that hill of decline.

And using the military as the prime placeholder for that which holds us together presents another set of problems. One of the key goals of those who planned the cultural and media response to 9-11 was to take a once broad field of social exemplarity where there were heroes of all social classes and types and reduce it to a space defined by narrowly conceived fixation on the military and those who wore uniforms. This, of course, played into the authoritarian and bellicose plans of the neocon warmongers who planned that propaganda effort.

But looking back, we can see that this not only placed an undue and unrealistic moral burden on our servicemen—they are, after all, principally in the business of killing and maiming— but led to a dangerous narrowing of the discourse, central to the creation and maintenance of every healthy culture in history, of what it means to be a good person and to live the “good life.”

And as for peace, it is difficult to make a convincing case for it when it is clear that the US leadership class, including the faction about to enter the White House, has shown itself to be wholly indifferent to the gruesome slaughter of tens of thousands of maimed and slain children in Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria.

Nope, largely limiting our repertoire of exemplarity to those who kill and those who get rich, with side helpings of praise for famous athletes and young women who exhibit surgically enhanced “beauty,” really won’t do the trick.

What exactly will, I don’t know.

What I do know is that problems, such as the dramatic winnowing and hollowing out of our public discourses of social exemplarity can never be repaired if we don’t talk about them.

When was the last time you talked in depth with a young person about what it means to live a good and fulfilling life as it is conceived of outside the parameters of economic gain or the game of acquiring reputation chits through the acquisition of titles and credentials?

My guess is that for most of us it has been longer than we care to admit. And my sense is that a lot of that reticence comes from the fact many of us have been worn down by the overwhelming pressure in our culture to be “pragmatic” and to not “waste time” thinking about big questions like “Why am I here?” and/or “What does it mean beyond to live an internally harmonious and spiritually satisfying life?

You know, those “spiritual” things that in recent years have been portrayed by our elite culture planners as, take your pick, a marker of being a loopy New Ager or a culturally intolerant Right-Winger.

But when we look at things in the broader expanse of history, it becomes clear that the real joke is likely to be on those who, desirous of achieving status in the pragmatically defined world, amputated their relationship to the world of holistic and reverent thinking. Or to put it in terms used by Ian McGilchrist, the joke is likely on those who passively subjugate the “master” who inhabits the big-thinking right hemisphere of the brain to the restless, narrowly focused “grabbing and getting” spirit of his “emissary” who inhabits in the left side of his cranium.

As contemporary thinkers as seemingly different as Stephen Covey and Joseph Campbell have argued, lasting satisfaction really only comes when we work, as it were, from the “inside out,” bringing what we have found to be more or less true in our own internal dialogues and pilgrimages “out” into our friendships and loveships, and from there, into the conversations we maintain with others in the public square.

If, as Todd suggests, we have lost the spiritual ethos that allowed the West to gain favor and power in the preceding centuries, we better get down to work on creating a new social credo, understanding as we do so that while those focused on the spirit often easily conceive of the matter that surrounds them, those obsessed with matter generally have a harder time of doing the opposite.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.