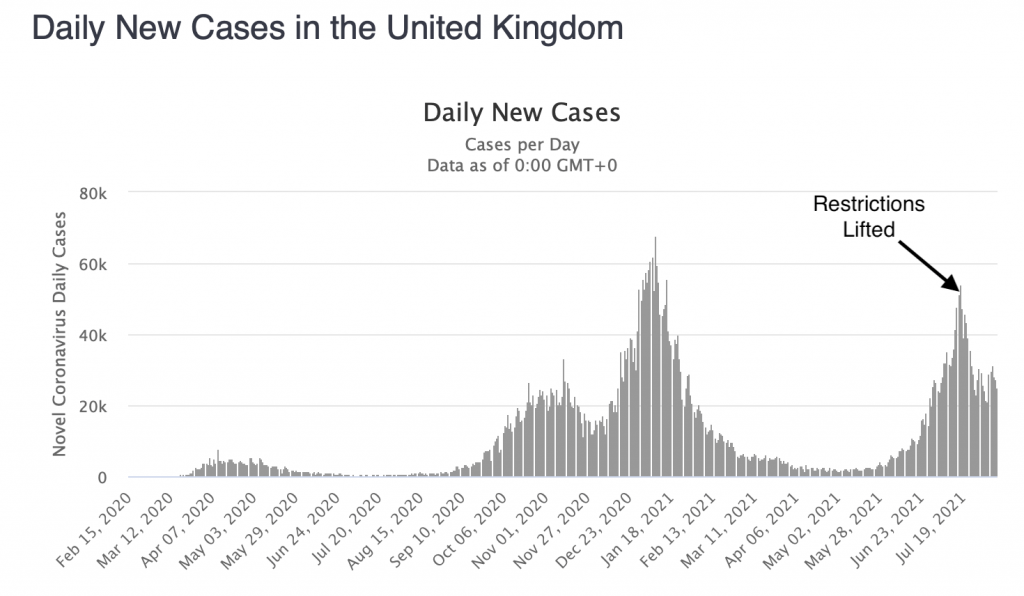

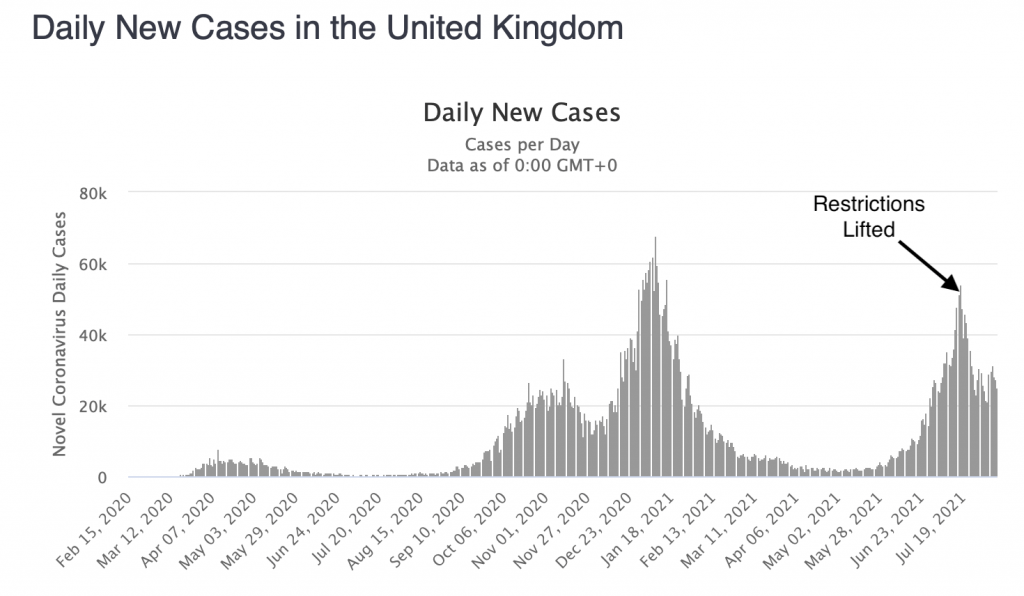

On Monday July 19, 2021, the UK government removed all distancing and masking restrictions, allowing, after sixteen months, the free assembly of people, and the re-starting of the many functions of our society that rely on us gathering together.

This decision was reported to be a ‘dangerous experiment’, a ‘global threat’, and all manner of predictions were made regarding the certainty that such a decision would lead to escalating case numbers. In fact, the opposite happened, and cases started dropping in the days following July 19.

This drop in cases, since the removal of distancing and masking restrictions in the UK, has exposed three incorrect assumptions that the whole pandemic response has been built on.

Assumption 1): The Illusion of Control

The idea that the government has the power to legislate restrictions on innate human behaviour, such as social contact, is false. This is a long-established reality in the discipline of public health, where ‘total abstinence’ behavioural policies have repeatedly been demonstrated to fail.

Humans have an innate drive to interact, socialise, mix, make new social and sexual relationships, and that need and the resultant behaviours cannot be removed by simple legislation. While the imposed restrictions made life miserable for many, humans remained human and mixing of course continued – and is essential for many of the basic functions of society to continue.

The belief that human behaviour simply followed government instruction was never the case, and therefore the removal of the legislation likely has not made as much difference to mixing as many anticipated.

Assumption 2) Illness Patterns Can Always Be Explained

This is incorrect. Medicine is full of examples of recognised patterns for illness trajectories, without clear reasons for the drivers of the pattern. So much is unknown, and much of the skill, or art, of being a doctor is in pattern recognition. We now know Covid has a distinct pattern. It comes, and goes, in waves, lasting around three to four months. This has been the case everywhere around the world, regardless of policy.

Unfortunately, our media cycles, and scientific attention, tend to focus on the part of the world that is currently in crisis, with the most number of Covid cases and the biggest strain on hospitals and healthcare systems, but when cases start to fall in those areas the attention is moved elsewhere.

This perhaps reflects a tendency for many media organisations, and scientific institutions, to treat these epidemic hotspots as objects with which to inject a dose of fear to boost their preferred policy proposals.

Conversely, if areas with high case numbers were approached with concern and open curiosity, then perhaps our media focus would not shift elsewhere as soon as the cases start to drop. This would allow for more learning around the inherent wave-like patterns of Covid transmission which have occurred repeatedly around the world. Like so much else in medicine, it is likely that these patterns can be described before the underlying drivers for the patterns are fully understood.

Assumption 3) Scientific and Medical Institutions Have the Answers

Responding to a pandemic is a complex problem, which requires a cross-disciplinary understanding of human behaviour, ethics, philosophy, data interpretation, law, politics, sociology and more. Scientists, while they may have specific training on one aspect of our pandemic response, are no better placed at responding to this, in the round, than anyone else.

Some of the failures in our response results from a lack of understanding, with some of our scientific institutions, about the realities of human behaviour, democracy, human rights, the nature of illness, and our diverse relationships with health and mortality.

In my view, this is a failure of our institutional class which, as a result of economic inequality, tends to exist in a privileged bubble, removed from many of the innate realities of human behaviour, and is therefore poorly equipped to interrogate problems from the perspective of many of the individuals they seek to represent.

This is not to suggest that we should hastily do away with the experts; of course scientific expertise is hugely helpful in offering a framework to test, evaluate and critically appraise interventions. That, however, has not, by and large, happened. The restriction and lockdown based approach was introduced before it could be scientifically tested. They were framed as ‘scientific’ before they could be evaluated, and efforts to do this since then have largely been sidelined.

The outcome, from the exposure of these false assumptions, however, can actually be liberating and empowering. It has revealed that the authority that has been invested in scientific and medical institutions is misguided, and that the authority should, in fact, sit much closer to us as individuals and as communities.

We all need to be our own philosophers, to question, interrogate, and make sense of the world, in ways that fit with our own expertise, our understanding of our own behaviour and that of our communities.

We can not divert this questioning, power, and decision making all to scientific institutions. The scientific institutions do not have the answers – and nor should they claim to. The response to a crisis like the coronavirus pandemic, and even understanding the aetiology and transmission patterns, requires an understanding of society that goes far beyond that which can be understood in a narrow scientific framework alone. We are, all of us, with our own individual experiences, perspectives, and training, just as likely to come up with valid hypotheses and solutions, as those in scientific institutions.

There are, however, ways of ensuring that our responses are more rooted in the realities of human society and human behaviour than has been the case in the restriction-based Covid response. If our lives are organised in a way where we are truly living in community, with each other, where we come into contact with difference, and can hear one another and understand our different needs and desires, then perhaps we are just as likely, or even, more likely, than unrepresentative ‘ivory tower’ type institutions, to have a decent attempt at understanding of what is happening in the world with respect to any given crisis.

Certainly, there are many people taking part in conversations, across the globe, who have observed the world around them, been curious about how our societies are structured and organised, and observed the hollowness of the assumptions on which our models and response has been built, and how likely the predictions – of what would happen when restrictions were imposed or removed – were to be incorrect.

The lesson is that the questions, answers, and solutions are within the capacity of individuals in society to discern and implement. We do not need powerful institutions with legal rights over us to feed them to us, to legislate us, to coerce us.

We of course need expertise for specific technical help in all sorts of situations, but not to instruct us how we go about our lives down to the tiniest detail. We need to figure it out for ourselves; no institution can do this for us – and they very well might get it wrong. And the results can be catastrophic, as these last 18 months have demonstrated.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.