Alongside Brownstone author Jennifer Sey, I received honorable mention in Walter Bragman’s breathless Important Context: Leaked Brownstone Institute Emails Reveal Support for Child Labor, Underage Smoking. Bragman has chosen to attach the hashtag #Brownstonefiles in an obvious reference to the Twitter Files, but it’s somewhat less impactful. At the time of this writing it has a total of two subsequent tweets, both hostile to Bragman.

Bragman reports that in the leaked emails that he viewed, “Blumen offered up an anecdote about antiwar activist pages getting edited by a single, potentially automated user slowly over time.”

Bragman is correct. I brought up the Philip Cross story in an internal email on the Brownstone authors’ list. The story is an important one, which I had not thought about much since 2018 when it first broke. In light of recent news, this story looks quite different than it did five years ago. I will revisit that story in this current piece, and follow up with some analysis of how the world has changed in the last five years.

The story broke in 2018 when former British MP George Galloway, long known for his anti-war views, called out a mysterious Wikipedia editor named “Philip Cross” for making unflattering changes to his Wikipedia page. BBC News covered Galloway’s war of words with a mystery Wikipedia editor.

The subject of Galloway’s ire is a prolific Wikipedia editor who goes by the name “Philip Cross”. He’s been the subject of a huge debate on the internet encyclopaedia – one of the world’s most popular websites – and also on Twitter. And he’s been accused of bias for interacting, sometimes negatively, with some of the people whose Wikipedia pages he’s edited.

The Philip Cross account was created at precisely 18:48 GMT on 26 October 2004. Since then, he’s made more than 130,000 edits to more 30,000 pages (sic). That’s a substantial amount, but not hugely unusual – it’s not enough edits, for example, to put him in the top 300 editors on Wikipedia.

But it’s what he edits which has preoccupied anti-war politicians and journalists. In his top 10 most-edited pages are the jazz musician Duke Ellington, The Sun newspaper, and Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre. But also in that top 10 are a number of vocal critics of American and British foreign policy: the journalist John Pilger, Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and Corbyn’s director of strategy, Seamus Milne.

His critics also say that Philip Cross has made favourable edits to pages about public figures who are supportive of Western military intervention in the Middle East.

…

“His edits are remorselessly targeted at people who oppose the Iraq war, who’ve opposed the subsequent intervention wars … in Libya and Syria, and people who criticise Israel,” Galloway says.

Mintpress published in an excellent digest of commentary around this issue and quotes Ron McKay in the Edinburgh Sunday Herald:

You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to see that there are common threads here. All of those [targeted] are… prominent campaigners on social media and in the mainstream media vigorously questioning our foreign policy.

Former UK Ambassador Craig Murray, also known for anti-war views and for his support of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, made a similar point:

[…] the purpose of the “Philip Cross” operation is systematically to attack and undermine the reputations of those who are prominent in challenging the dominant corporate and state media narrative, particularly in foreign affairs.

Anti-war site medialens.org asked:

Other notable anti-war voices such as Noam Chomsky, Edward S. Herman (co-author of the book Manufacturing Consent), and Rania Khalek were also subject to Cross’s relentless campaign of defacement.

Amb Murray, observed the following astonishing facts:

The unidentified editor, “account is responsible for 20.4% of all edits” of Galloway’s page (which Cross had edited over 1800 times), said the BBC, which continues to detail the contents of specific edits which were entirely in the unflattering or negative direction.

UPDATE “Philip Cross” has not had one single day off from editing Wikipedia in almost five years. “He” has edited every single day from 29 August 2013 to 14 May 2018. Including five Christmas Days. That’s 1,721 consecutive days of editing.

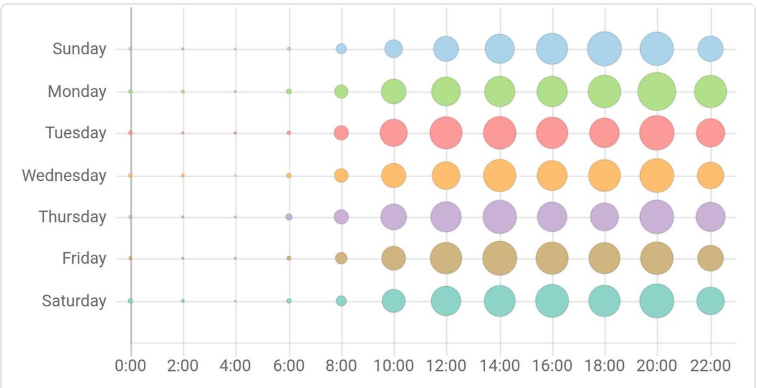

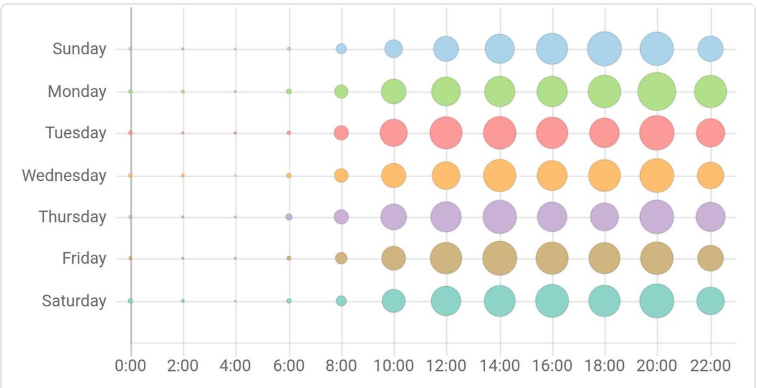

So, 133,612 edits to Wikipedia have been made in the name of “Philip Cross” over 14 years. That’s over 30 edits per day, seven days a week. And I do not use that figuratively: Wikipedia edits are timed, and if you plot them, the timecard for “Philip Cross’s” Wikipedia activity is astonishing if it is one individual:

The operation runs like clockwork, seven days a week, every waking hour, without significant variation.

Amb Murray provided the following graph of “Philip Cross’s” productivity in altering Wikipedia pages by day of the week averaged over the 14 years of activity:

Who is or was this Philip Cross? Subsequent to the above-mentioned BBC article, Cross retired from his career of vandalism ranked #308 among most active all-time Wikipedia editors. His former Twitter account @philipcross63 no longer exists. No one who knows, tells. Galloway thinks that Cross is a “real and vulnerable person.”

Amb Murray notes that Galloway had at one point offered a reward of £1,000 for the identity of this person or entity, “so he may also take legal action.” MediaLens states that “BBC Trending has been able to establish that he lives in England, and that Philip Cross is not the name he normally goes by outside of Wikipedia.” Everipedia.org states “Cross is a jazz and drama enthusiast.” I suspect that he probably also likes long walks on the beach and curling up in front of an open fireplace with a copy of the New York Times.

Amb Murray offers:

There are three options here. “Philip Cross” is either a very strange person indeed, or is a false persona disguising a paid operation to control wikipedia content, or is a real front person for such an operation in his name.

and

My view is that Philip Cross probably is a real person, but that he fronts for a group acting under his name. It is undeniably true, in fact the government has boasted, that both the MOD and GCHQ have “cyber-war” ops aiming to defend the “official” narrative against alternative news media, and that is precisely the purpose of the “Philip Cross” operation on Wikipedia. The extreme regularity of output argues against “Philip Cross” being either a one man or volunteer operation. I do not rule out however the possibility he genuinely is just a single extremely obsessed right wing fanatic.

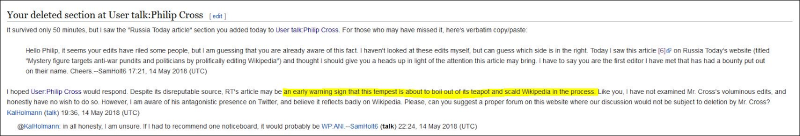

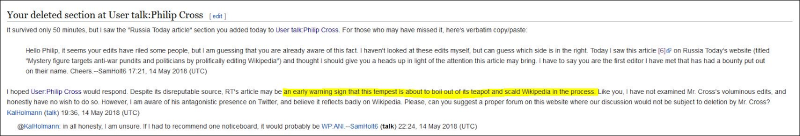

A Wikipedia editor in a side channel expressed concern that Wikipedia’s reputation (such as it is) might be when light was shone on the unusual activities of “Philip Cross.”

Did the story have a happy ending? In August of 2018, reported by Five Filters, “Wikipedia’s arbitration committee (ArbCom) has finally voted to ban editor Philip Cross from the topic of ‘post-1978 British politics’.” But wait – not so fast. “In a petty tit-for-tat move, however, Wikipedia’s arbitration committee decided it would also punish the editor who tried to alert the community to Philip Cross’ conduct.”

I was aware of the Philip Cross story when it broke in 2018. At the time I did not have an explanation for it. It seemed eerily odd to me and I was not thinking about bots or natural language automation.

The recent groundbreaking Twitter revelations of the existence and massive scale of an organized censorship-industrial complex (CIC) make suspicions of official sector censorship, perhaps in an earlier iteration five years ago, far more plausible. FiveFilters.org wrote in 2018, “Nearly All of Wikipedia Is Written By Just 1 Percent of Its Editors.” The same piece cites a Daniel Oberhaus article in Vice from 2017 about the concentration of Wikipedia editing:

But as the encyclopedia grew, and the number of collaborators grew with it, a cadre of die-hard editors emerged that have accounted for the bulk of Wikipedia’s growth ever since.

Matei and his colleague Brian Britt, an assistant professor of journalism at South Dakota State University, used a machine learning algorithm to crawl the quarter of a billion publicly available edit logs from Wikipedia’s first decade of existence. The results of this research, published September as a book, suggests that for all of Wikipedia’s pretension to being a site produced by a network of freely collaborating peers, “some peers are more equal than others,”

The long-form piece on racket.news cites multiple instances of CIC actors using AI and natural language processing. The Public Goods Project, for example,

use AI and natural language processing to ‘identify, track, and respond to narratives, trends, and urgent issues’ in order to ‘perform fact-checking’ and ‘power behavior change strategies.’

A recent story on Igor Chodov’s substack, Bill Gates-Funded AI Chatbots Promoted COVID Vaccines (You may have encountered them on social networks) which cites a nature.com article Effectiveness of chatbots on COVID vaccine confidence and acceptance in Thailand, Hong Kong, and Singapore provides more information about the use of bots in the service of controlling narratives.

The recent emergence of high-performing large language models makes the idea of automation more plausible. If not in 2018, an LLM could now easily rewrite a given text to slant it in the prompted direction.

Were there models that could do this at that time? Will future campaigns to control Wikipedia narratives rely on this technology? What is the future of a crowd-sourced knowledge base such as Wikipedia that depends on the high cost in human time and social interaction of making an edit to a controversial topic when the ability to automate this makes it close to free?

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.