Nearly the whole of the professional, intellectual, and government class has betrayed the cause of universal human liberty in our times. But among those who were supposed to be less susceptible were the people called libertarians. They fell too, and tragically so. This subject is especially salient to me because I have long considered myself to be among them.

“If only there were a political movement focused on making the government get out of the way and just leave you alone,” famed whistleblower Edward Snowden has written from exile in Russia. “An ideology to answer the growing prison-planet problem. Name it something that evokes the spirit of liberty, you know? We could all use some of that.”

If only. I among many people thought we had such a thing. It was built over many decades of focused intellectual work, sacrificial funding, countless conferences, a library of books, and many nonprofit organizations the world over. It was called libertarianism, a word recaptured in 1955 as a new name for the old liberalism and then further refined over the decades.

The last four years should have been a great moment for the ideological movement that went by that name. The total state – official compulsion in every area of life – had never been more on display in our lifetimes, shutting small businesses and closing churches and schools, even imposing visitor limits in our own homes. Liberty itself came under crushing attack.

Libertarianism had for decades if not centuries condemned overweening government power, industrial cronyism, interventions in commerce freedom, and the deployment of coercion in place of the free and voluntary choices of the population. It had celebrated the capacity of society itself, and especially its commercial sector, to create order without imposition.

All that libertarianism had long opposed reached its apotheosis of absurdity in four years, wrecking economies and cultures and violating human rights, and with what result? Economic crisis, ill-health, illiteracy, distrust, population-wide demoralization, and the generalized pillaging of the commonwealth at the behest of the ruling class elite.

There was never a better time for libertarianism to scream: we told you so, so stop doing this. And not only for purposes of being right but also in order to provide light for a post-lockdown future, one that would promote confidence in self-organizing social orders rather than central managers.

Instead, where are we? There is every bit of evidence that libertarianism, as a cultural and ideological force, has never been more marginal. It seems barely to exist as a brand. This is not an accident of history but a consequence, in part, of a certain tone-deafness on the part of the leadership. They simply declined to seize the moment.

There is another issue that is more philosophical. Several pillars of libertarian orthodoxy—free trade, free immigration and open borders, and its uncritical pro-business stance—have all come under serious strain at the same time, leaving adherents struggling to figure out the new lay of the land and lacking a voice to respond to the current crisis.

As a bellwether, consider the current Libertarian Party.

In a narrow vote and lacking serious alternatives, it nominated Chase Oliver as their presidential candidate for 2024. Very few had ever heard of him before. Deeper research demonstrated that during the most totalitarian exercise of state power in our lifetimes, Oliver posted frequently in a fear-mongering vein, utterly missing the moment and blind to the despotism as it emerged.

Oliver bragged of always masking (often) and never meeting in crowds (unless it was for the BLM protest), defended and pushed for vaccine mandates for business, urged on his social media followers to follow CDC propaganda, and celebrated Paxlovid (later proven worthless) as the key to ending lockdowns, which he only expressly opposed 20 months after they were imposed.

In other words, he not only failed to challenge the core of Covid ideology—that other human beings are pathogenic so we need to restrict our freedoms and isolate—but used his social media presence, such as it was, to urge others to accept all the dominant lies by the government. He bought the Covid and lockdown ideology and broadcasted it. He seems to have no regrets.

He is hardly alone. Nearly the whole of the media/academic/political establishment was with him on all of this. This is four years following the previous Libertarian Party national candidate who, during the thick of the lockdown crisis, had nothing to say, a failure that led to upheaval in the party. The new faction swore to defend actual liberty but enough grass-roots delegates apparently disagreed and defaulted to the old model.

To be sure, you could say that this is purely a failure of a long-dysfunctional third party. But what if there is more going on here? What if libertarianism as such has melted as a cultural and intellectual force too?

Earlier this summer, the closure of the organization FreedomWorks unleashed the ultimate spin: the libertarian moment is over. The goal of cutting government, freeing trade, lowering taxes, and prioritizing liberty is no more, wrote Laurel Duggan in Unherd. “In 2016, a number of prominent US conservatives gathered to formally debate whether the much-vaunted ‘libertarian moment’ was merely a mirage.” he writes. “Nearly a decade later, the American Right’s libertarian contingent has seemingly been dealt its final blow.”

The institutional meltdown that I’ve watched for nearly ten years might be accelerating. So much has been wrecked by failures: of timing, organizing, strategy, and theory. As the conventional wisdom says, the rise of Trump, with its two pillars of protectionism and immigration restrictions, does indeed fly in the face of the libertarian spirit. The dogma seemed to fit the facts ever less, while the temptation toward protectionism and border restriction was just too powerful.

Therefore let us begin with the larger picture, the smattering of issues that have been top of the list in liberal/libertarian circles for a very long time.

Trade

Consider the issue of trade, central to the rise of liberalism in the post-feudal period from the late Middle Ages onward. Sometimes called Manchesterism in the 19th century, the idea was that no one should care about which nation states were trading what with whom but rather that laissez-faire should prevail.

Manchesterism stands in stark contrast to Mercantilism, the protectionist idea that a nation should seek to guard its industries from foreign competition at any cost, keeping as much money inside the country as possible, via tariffs and blockades and other measures.

The Manchester doctrine of free trade posited that everyone benefits from the freest trade possible and that all fears of losses of currency and industry are wildly overblown. It’s been central to the libertarian tradition in the UK and US. But over half a century since the loss of the gold standard, the manufacturing base of the US underwent a huge upheaval as textiles and then steel left US shores, gutting cities and towns of industries that were not easily converted to other purposes, leaving carcasses of facilities to remind residents of a time gone by.

It’s mostly all gone: clocks, textiles, apparel, steel, shoes, toys, tools, semiconductors, home electronics and appliances, and much more. What remains are boutiques making high-end products priced far higher than the mainstream market. They appeal to the elite, unlike the tradition of American manufacturing which was to make products for the masses of consumers.

As market defenders have long said, this is just what happens when half the world that was previously closed opens up, China in particular. The division of labor expands globally, and there is nothing to be gained by taxing citizens to preserve manufacturing that can take place more efficiently elsewhere. Consumers benefited greatly. Adjustment among the production sector was inevitable, unless you want to pretend like the rest of the world doesn’t exist, which many Trump supporters now favor.

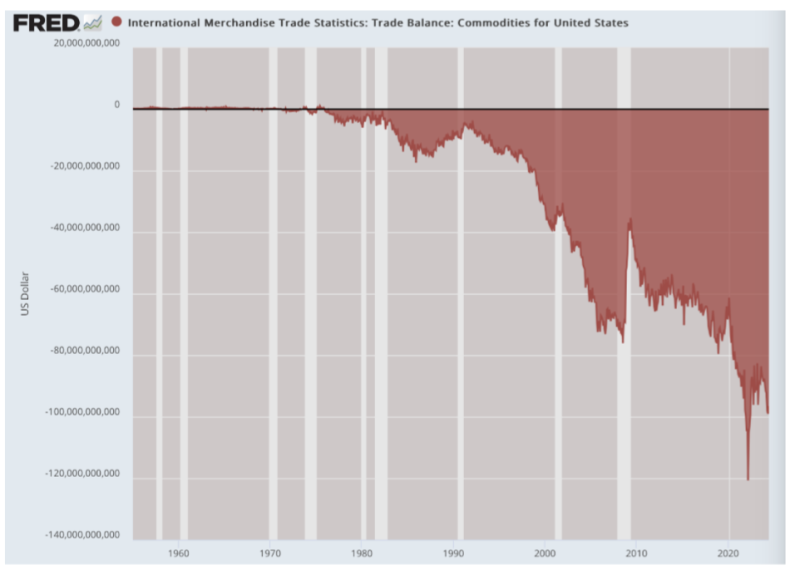

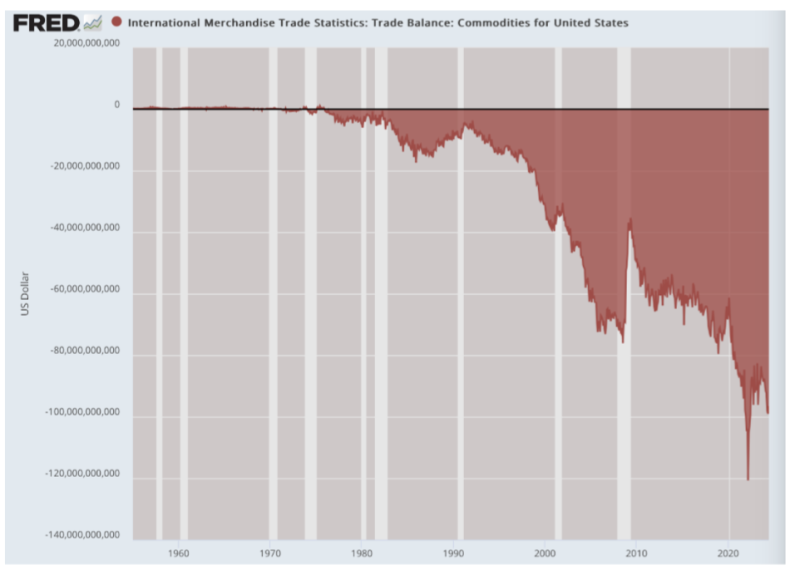

But along with that, there were other problems brewing. Free-floating exchange rates with a global dollar standard based on fiat gave the strong impression that the US was actually exporting its economic base as the world central bank accumulated dollars as assets, without the natural corrections that would have happened under a gold standard. Those corrections involve falling prices in importing nations and rising prices in exporting nations, leading to a rebalancing of the two. The balance can never be perfect of course but there is a reason that the US in postwar history never ran consistent, much less rising, trade deficits until 1976 and following.

Free trade economists from David Hume in the 18th century to Gottfried Haberler in the 20th century had long explained that trade is no threat to domestic production because of the price-specie flow mechanism. This system worked as an international settlement mechanism in which prices would adjust in each country based on monetary flows, turning exporters to importers and back again. It was precisely because of this system that so many free traders have said it is a waste of time to follow the balance of payments; it all works out in the end.

That absolutely stopped working in 1971. That changed matters substantially, and for decades now the US has stood by as mountains of US debt assets served as collateral for foreign central banks to build up their manufacturing base to directly compete with US producers with no settlement system in place at all. The reality is reflected in the trade deficit data but also in the loss of capital, infrastructure, supply chains, and skills that once made America the world’s leader in consumer goods manufacturing.

Even as this took place abroad, business creation became ever more difficult at home with high taxes and intensifying regulatory controls that made enterprise ever less functional. Such costs ended up making competition even more difficult to the point that waves of bankruptcy were inevitable. Meanwhile, the managers of the price level could never tolerate a rising purchasing power in response to money/debt exports, and continued to replace outward money flows with new supplies so as to prevent “deflation.” As a result, the price-specie flow mechanism of old simply ceased to operate.

And that was only the start of it. Henry Hazlitt in 1945 explained that balance-of-trade issues are themselves not the problem but they serve as an indicator of other problems. “These may consist of pegging its currency too high, encouraging its citizens or its own government to buy excessive imports; encouraging its unions to fix domestic wage rates too high; enacting minimum wage rates; imposing excessive corporation or individual income taxes (destroying incentives to production and preventing the creation of sufficient capital for investment); imposing price ceilings; undermining property rights; attempting to redistribute income; following other anti-capitalistic policies; or even imposing outright socialism. Since nearly every government today—particularly of “developing” countries—is practicing at least a few of these policies, it is not surprising that some of these countries will get into balance-of-payment difficulties with others.”

The US has done all these things, including not just pegging the currency too high but becoming the world reserve currency and the only currency in which all energy trades took place, together with subsidizing the industrial build-out of nations around the world to compete directly with American firms, even as the US economy has become ever less adaptable to change and response. In other words, the problems were not due to free trade as traditionally understood. In fact, the idea of “free trade” was unnecessarily scapegoated throughout. Nonetheless, it has lost popular support as an easy cause-and-effect has proven highly tempting: free trade abroad leads to domestic decline.

In addition, huge trade agreements like Nafta, the EU, and the World Trade Organization were sold as free trade but they were actually heavily bureaucratized and managed trade with corporatist substance: trade authority not by property owners but by bureaucracies. Their failure was blamed on something they were not and never intended to be. And yet, the libertarian position throughout has been to let it rip, as if none of this is a problem while defending the results. Decades have gone by and the backlash is fully here but libertarians have consistently defended the status quo, even as left and right have both agreed to abandon it in the face of all evidence that “free trade” is not going as planned.

The real answer is a dramatic domestic reform, balanced budgets, and a sound monetary system but these positions have lost their cache in public culture.

Migration

The immigration issue is more complex still. Reagan-era conservatives celebrated more immigration based on rational and legal standards of bringing more skilled workers into the fabric of a welcoming nation. In those days, we never imagined the possibility that the entire system could become so gamed by cynical political elites to import voting blocs to skew elections. There had always been questions about how viable open borders could be with the presence of a welfare state but using such policies for overt political manipulation and vote harvesting is not something that most people had even considered as possible.

Murray Rothbard himself warned about this problem in 1994: “I began to rethink my views on immigration when, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it became clear that ethnic Russians had been encouraged to flood into Estonia and Latvia in order to destroy the cultures and languages of these peoples.” The problem concerns citizenship in a democracy. What if an existing regime exports or imports people for the precise point of unsettling demographics for reasons of political control? In that case, we are not talking about just economics but crucial matters of human liberty and regime hegemony.

The reality of millions brought in under migrant programs, funded and supported by tax dollars, raises profound problems for the traditional libertarian doctrine of free immigration, particularly if the political ambition is to make the domestic economy and society even less free. Incredibly, the waves of illegal immigration were permitted and encouraged at a time when it was increasingly difficult to immigrate legally. In the US, we found ourselves in the worst of both worlds: restrictive policies toward migration (and work permits) that would enhance freedom and prosperity even while millions flooded in as refugees in ways that could only harm the prospects for freedom.

This problem, too, has brought about a full political backlash, and for reasons that are entirely understandable and defensible. People in a democratic system are simply unwilling to have their tax dollars deployed and their voting rights diluted by hordes of people who have no historic investment in maintaining their traditions of freedom and the rule of law. You can lecture people all day about the importance of diversity but if the results of demographic upheaval clearly spell more servitude, the native population will not be entirely welcoming of the results.

With those two pillars of libertarian policy brought into question, and pummeled politically, the theoretical apparatus itself began to appear ever more fragile. The rise of Trump in 2016, who focused on these two issues, trade and immigration, became a huge problem as populist nationalism replaced Reaganism and libertarianism as the prevailing ethos within the GOP, even as the opposition drifted ever more toward traditional social-democratic affection for state planning and left-socialist idealism.

The Statism of the Corporate Elite

The Trump movement also kicked off a dramatic turning in American political life within the corporate and business world. The high-end sectors of all the new and old industries—tech, media, finance, education, and information—turned against the political right and began to court alternatives. This meant the loss of a traditional ally in the push for lower taxes, deregulation, and limited government. The largest companies began to become allies of the other side, and that included Google, Meta (Facebook), Twitter 1.0, LinkedIn, plus the pharmaceutical giants which are famously cooperative with the state.

Indeed, the whole corporate sector proved itself far more politically nihilistic than anyone expected, more than thrilled to join up in a huge corporatist push to unite public and private into a single hegemon. After all, government had become its largest customer, as Amazon and Google made contracts with government worth tens of billions, making the state the single most powerful influence over managerial loyalties. If under the market economy, the customer is always right, what happens when the government becomes a main customer? Political loyalties shift.

This runs counter to the simple paradigm of libertarianism which had long pitted power against the market as if they were always and everywhere enemies. The history of corporatism in the 20th century shows otherwise of course but the corruption in the past had usually been limited to munitions and large physical infrastructure.

In the digital age, the corporatist form invaded the whole of civilian enterprise all the way down to the individual cellphone, which went from a tool of emancipation to become a tool of surveillance and control. Our data and even our bodies had become commoditized by private industry and marketed to the state to become instruments of control, creating what has been called techno-feudalism to replace capitalism.

This shift was something for which conventional libertarian thinking was not prepared, intellectually or otherwise. The deep instinct to defend the publicly traded for-profit private company no matter what created blinders to a system of oppression that was decades in the making. At some point in the rise of the corporatist hegemon, it became difficult to figure out which was the hand and which was the glove in this coercive hand. Power and market had become one.

As a final and devastating blow to the traditional understanding of market mechanisms, advertising itself became corporatized and allied with state power. This should have been obvious long before big advertisers attempted to bankrupt Elon Musk’s platform X precisely because it allows some measure of free speech. That is a devastating commentary on where matters stand: the major advertisers are more loyal to states than to their customers, perhaps and precisely because states had become their customers.

Similarly, Tucker Carlson’s show at Fox was the most highly rated news show in the US, and yet faced a brutal advertising boycott that led to its cancellation. This is not how markets are supposed to work but it was all unfolding before our eyes: big corporations and especially pharma were no longer responding to market forces but instead were currying favor with their new benefactors within the structure of state power.

The Squeeze

Following the triumph of Trump on the right—complete with its protectionist, anti-immigrationist, and anti-corporate ethos—libertarians had nowhere to turn, as the anti-Trump forces seemed animated by an anti-liberal impulse too, and even more so. Over the subsequent four years, libertarian energy depleted dramatically as the old guard became increasingly defined by whether it would support or resist Trump, with ideological coloration following in kind. The magic center of the libertarian and classical liberal idea—to make expanding freedom the sole aim of politics—became internally squeezed by either side.

The proof of the weakness of institutionalized libertarianism was really exposed in March 2020. What was called the “liberty movement” had hundreds of organizations and thousands of pundits, with events scheduled regularly in the US and abroad. Every organization bragged about the expansion of staff and their supposed achievements, complete with metrics (which became all the rage among the donor class). It was a well-funded and self-satisfied movement that imagined itself to be robust and influential.

But, when governments around the country literally took a sledgehammer to free association, free enterprise, free speech, even the freedom of worship, did the “liberty movement” fly into action?

No. The Libertarian Party had nothing to say, even though it was an election year. The “Students for Liberty” sent out a message urging everyone to stay home. “We will be spreading liberty, not corona. Watch this space for our upcoming #SpreadLibertyNotCorona campaign,” wrote the SFL president. He celebrated that “We have access to tools that can move most work into a remote environment,” forgetting entirely that some people, not elite think tankers, have to deliver the groceries.

Most everyone else in elite quadrants of society—with only a few in dissent—stayed quiet. It was a deafening silence. The Mont Pelerin Society and Philadelphia Society were absent from the debate. Most of these nonprofits went into full turtle mode. They can claim now that activism was not their role, and yet both organizations were born in the midst of a crisis. The whole point of their existence was to address them directly. This time it was all-too-convenient to say nothing even as the businesses were shut and the schools and churches closed by force.

In other liberty-aligned circles, there was active support for some features of the lockdown-until-vaccinate agenda. Some arms of the Koch Foundation backed and awarded Neil Ferguson’s modeling that proved so wrong but whipped the Western world into a lockdown frenzy, while Koch-backed FastGrants cooperated with crypto-scam FTX to fund the designed-to-fail debunking of Ivermectin as a therapeutic alternative. These relationships involved many millions in funding.

In theoretical/academic circles, conducted on email in my experience, there were strange parlor debates on whether and to what extent the passing on of an infectious disease might constitute the very form of aggression against which libertarianism had long condemned. The “public goods” problem of vaccines was also hotly debated, as if the issue was somehow new and the libertarians had just heard of it.

The prevailing attitude became: Maybe there was a point to the lockdowns after all and perhaps libertarianism should not be so quick to condemn them? This was the point of a major position paper that came out from the Cato Institute, a canonical statement appearing eight months after lockdowns, that endorsed masking, distancing, closures, and tax-funded vaccines and mandates to take them. (I’ve critiqued this in detail here.)

It should go without saying that lockdown is the opposite of libertarianism, regardless of the excuse. Infectious disease has been around since the beginning of time. Are these libertarians just now coming to terms with this? What can one say about a massive intellectual industry that is shocked by the existence of pathogenic exposure as a living reality?

And what about the sheer class brutality of lockdowns that enable the laptop class ultimate luxury and condemn the working classes to serve them while risking disease exposure? Why is this not a problem for an ideology that idealizes universal emancipation?

Many of the organizations and spokesmen (even the supposed anarchist Walter Block) had already said as much. Professor Block had long defended the 30-year incarceration of “Typhoid Mary” (Irish immigrant chef Mary Mallon) as a wholly legitimate action of the state, even with all remaining doubts about her culpability and with full knowledge that hundreds if not thousands of others were similarly infected. Even “to sneeze in someone’s face” is “akin to assault and battery” and should be punishable by law, he wrote. Meanwhile, Reason Magazine figured out some way to defend masks even as mandates were sweeping the country, among other fashionable concessions to lockdown mania, especially on the topic of vaccines.

Then there was the subject of vaccine mandates as imposed by businesses. The typical libertarian answer was that business can do what it wants because it is their property and their right to exclude. Those who don’t like it should get another job, as if that were an easy proposition and no big deal to hurl people out of their jobs for refusing an untested new injection they did not want or need. Many libertarians put business rights ahead of individual rights, without considering the role of government in imposing these mandates in the first place. Moreover, this position fails to consider the profound problem of liability. The vaccine companies were indemnified by law and that extended to the institutions mandating, thus robbing all workers of any recourse in the case of injury or relatives any compensation in the case of death.

How and why this happened is still a mystery but it surely revealed an underlying weakness that is disclosed when an ideological structure had never really faced a foundational stress test. Honestly, if one’s libertarianism cannot manage to oppose decisively a global lockdown of billions of people in the name of infectious disease control, complete with track-and-trace and censorship, even though the disease had a 99-plus percent survival rate, what possible good is it?

At that point, the doom of the machinery was already set in motion and it was only a matter of time.

Tactical Issues

At a deeper level, I’ve personally observed several additional problems within libertarianism over my career, all of which were fully revealed in the embarrassing period in which lockdowns came to be either ignored or even permissioned by most official voices within this camp:

- Professionalization of activism. In the 1960s, the libertarians were mostly employed in other tasks: professors, journalists with mainstream outlets and publishers, business people with views on things, and really only one small organization with a tiny staff. The idea at the time was that all of this would expand and the masses would be educated when the ideology became a job with a professional aspiration. As politics is downstream from such education, revolution would be in the bag.

Thanks to idealistic industrial benefactors, the liberty industry was born. What could go wrong? Essentially, everything. Instead of smartly pushing out ever more clear theory and policy ideas, the first priority of the newly minted libertarian professionals became securing employment within the growing industrial machinery associated with the ideology. Instead of attracting ever more sophisticated thinkers who were ever better at responding and messaging, the professionalization of libertarianism over several decades ended up attracting people who wanted a good job at a high wage, and climbing the corporate ladder by keeping actual talent at bay. Risk aversion became the rule over time, so when wars and bailouts and lockdowns happened, there was an institutionalized aversion to rocking the boat too much. Radicalism mutated into careerism. - Organizational mismanagement. Along with this professionalization came the valorization of the non-profit organization without market metrics and without a drive to do much besides build and protect itself and its funding base. The major intellectuals and “activists” inhabited a huge sector that was literally separated from the very market forces it sought to defend. That’s not necessarily fatal but when you combine such institutions with professional opportunism and managerial bloat, you end up with large institutions that exist mainly to perpetuate themselves. Getting funded was job one, and all the organizations found their strength in networked numbers, sending endless and voluminous fundraising letters proclaiming their victories even as the world was becoming ever less free.

- Theoretical arrogance. The word libertarian is a postwar neologistic successor to the word liberal that had defined the ideological impulse a century earlier. But instead of sticking to the general aspirational and more peaceful and prosperous societies through freedom, 1970s-style libertarianism became ever more rationalistic and prescriptive on every conceivable problem in human society, with precise opinions on every controversy in human history. It never intended to create an alternative central plan but there were times when it seemed close to doing so. What is the libertarian answer to this or that problem? The bromides came fast and furious, as if the “best and brightest” intellectuals could be counted on to guide us to a new world through well-produced video tutorials.

Along with the drive to popularize the ideology came a push to reduce its postulates to simple syllogisms, the most popular of which was the “non-aggression principle” or NAP for short. It was a decent slogan if you see it as a summary statement of a large literature tracking back through Murray Rothbard, Ayn Rand, Herbert Spencer, Thomas Paine, and back further through a huge diversity of fascinating intellectuals across many continents and ages. It hardly works at all, however, as a single ethical prism through which to view all human activity, but that is how it came to be rendered in times when learning took place not through large treatises but through memes on social media.

That invariably led to the dramatic dumbing down of the whole tradition of thought, with everyone invited to invent their own versions of what the NAP means to them. But there was a problem. No one could agree on what aggression is (if you think you know, consider what it means to have an aggressive ad campaign) or even what it means to be a principle (a law, an ethic, a theoretical device?).

For example, it leaves unsettled issues such as intellectual property, air, and water pollution, property rights in air, banking and credit, punishment and proportionality, immigration, and infectious disease, issues on which there was a huge and useful debate that was at cross purposes with the goal of popularizing and sloganizing.

To be sure, there are answers to how to deal with all of these issues using liberal policies but understanding them requires reading and careful thought, and possibly adaptation given the circumstances of time and place. Instead of that, we suffered through many years of the “chirping sectaries” problem identified by Russell Kirk in the 1970s: a war of endless factions that became ever more vicious and eventually ate into the big picture of what it is we are going for in the first place.

No one had time for the humble intellectual exploration that characterizes robust intellectual societies in the go-go post-millennium culture of institutional expansion, professional aspiration, and making a splash as a libertarian influencer. As a result, the theoretical foundations of the entire apparatus became ever thinner even as the popular consensus against laissez-faire theory was decaying. - Errors in strategic outlook. Liberalism has generally been prone to a kind of Whiggish understanding of itself as historically inevitable and somehow baked into the cake of history, ushered in by market forces and people power. Murray Rothbard had always warned against this outlook but his warnings were unheeded. Speaking for myself, without knowing it, I had personally adopted a 19th-century Victorian-style confidence in the victory of liberty in our time. Why? I saw digital tech as the magic bullet. It meant that freedom of information flows would leave the physical world and become infinitely reproducible, gradually inspiring the world to overthrow their masters. Or something like that.

Looking back now, the whole position was naive in the extreme. It overlooked the problem of industry cartelization by regulation and capture by the state itself. It also conflated the spread of information with the spread of wisdom, which mostly certainly didn’t happen. The entirety of industrial development in the last five years has left me and many libertarians feeling deeply betrayed by the very systems we once championed.

What we expected to emancipate us has imprisoned us. Major swaths of the Internet consist of state actors now. The failure is nowhere better illustrated than by what’s happened to Bitcoin and the crypto industry, but that is a subject for another time.

Some of this failure could not be helped. Facebook went from libertarian organizing tool to a display of only state-approved information, thus disabling a major tool of communicating. Something similar happened to YouTube, Google, LinkedIn, and Reddit, thus silencing and separating voices that had long trusted such venues to get the word out.

We are left with problems today that seem very old-fashioned. Business is cartelizing and joining up with powerful states into a corporatist combine. It is happening not just on a national level but a global one. The managerial state has insulated itself from democratic forces, raising real questions of how to combat it.

The idealism of universal liberation ever more feels like a pipe dream taking place in a living room that is ever smaller, while the “movement” we once thought we had has become a dumbed-down, career-driven, money grubbing, and uninspiring corpse that only rouses itself to dance for a dwindling number of elderly people among the donor class. In other words, it is the perfect time for old-fashioned freedom to sweep in with a clear vision of where we need to go.

This ought to be the libertarian moment. It is not.

To be sure, there were some outliers among the libertarians, some voices that stood up and stood out, early on, and those same people are still consistently defending liberty as the answer to social, economic, and political problems. I would list them but I might leave some out. That said, one voice stands out and deserves maximum praise: Ron Paul. He is from that early generation of libertarians who understood priorities and he deployed also his scientific background in the case of Covid, with the result that he was 100% correct from day one. His son Rand has been a leader throughout. Ron and others were a distinct minority and took grave risks to their careers in doing so. And they had almost no institutional backing, not even from self-described libertarian organizations.

The Reinvention

Regardless, it should create an opportunity to regroup, rethink, and rebuild on a different foundation, with fewer deployments of hammer-and-tongs ideological agitation as an end in itself, less professional opportunism, more vision of the big goals, more attention to facts and science, and a greater inclusion of intellectual engagement and real-world concern and communication across the political divide. Edward Snowden is exactly right: the plain aspiration of a free life should not be such a rarity. Libertarianism, properly conceived, should be a common way to think about the current crisis.

Above all, libertarianism needs to rediscover sincere passion and a willingness to tell the truth in hard times, same as motivated abolitionist movements in the past. That is what is missing above all else, and perhaps the reason for this is due to a lack of intellectual seriousness plus careerist-centered caution. But as Rothbard used to say, did you really think that being a libertarian would be a great career move as compared with the choice to fit in with establishment propaganda? If so, someone was misled along the way.

Humanity desperately needs freedom, now more than ever, but it cannot necessarily count on the movements, organizations, and tactics of the past to get us there. Libertarianism as a general aspiration of a non-violent society is a beautiful one, but this vision can survive with or without the name and with or without the many organizations and influencers who claim the decaying mantle.

The aspiration survives, and so does the large literature, and you might find it alive and growing in places you least expect to find it. The supposed “movement” as represented by big-name institutions might be broken but the dream is not. It’s only in exile, like Snowden himself, safe and waiting in the unlikeliest of places.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.