Dear Editor:

In an ideal world of uncensored Covid science, I would have submitted this letter through the online submission website. However, my experience in 2021 and 2022 and more recently has taught me that there was zero chance that you would have published this text.It has been over four years since the following letter to the editor was published in your journal, but I discovered it only last month. I think there is no expiration date for the search for the truth, and I hope you agree.

Relying on data from 280 nursing homes across 21 states, the authors concluded: “These findings show the real-world effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines in reducing the incidence of asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in a vulnerable nursing home population.”

That is far from the truth.

First, they did not report a single estimate of effect, such as a risk (probability) ratio. That the authors conclude “real-world effectiveness” without showing any estimate is astonishing. It is also astonishing that peer-reviewers or the editorial board have allowed that to happen.

Second, in every nursing home an unvaccinated resident was followed at least three weeks longer than a fully vaccinated resident, so their risk (probability) of infection was higher. Time at risk was neither reported nor considered.

Third, a key risk ratio I will shortly compute from the data is confounded by time trends in the background risk of an infection.

Fourth, comparing the risk ratio of infection (mucosal immunity) with the risk ratio of symptoms if infected (systemic immunity), we observe implausible results.

Lastly, a rudimentary correction suggests near-zero effectiveness of two doses of an mRNA vaccine in this population.

To set the record straight, I offer a peer review of the study and show several risk ratios.

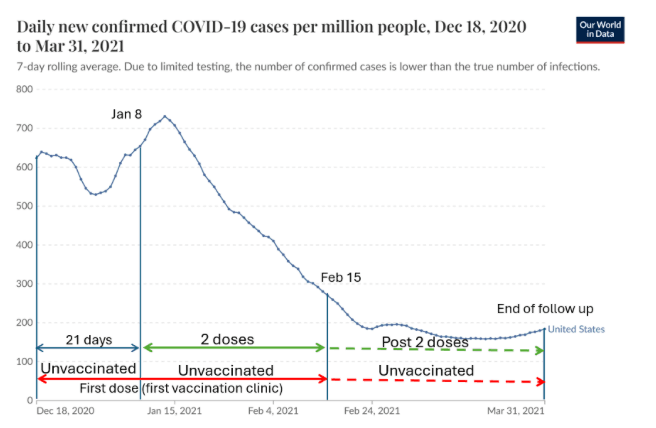

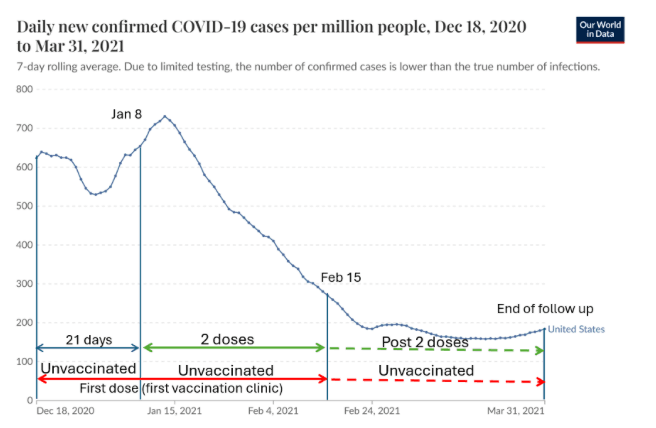

The first dose of an mRNA vaccine was administered on December 18, 2020. Follow-up of nursing home residents who received two doses began at least 21 days later, on January 8, and lasted till March 31. The timeline is shown in the figure along with the epidemic curve.

Unvaccinated residents “were present at their facility on the day of the first vaccination clinic” (i.e., at the time of the first dose, if administered by February 15) and were not vaccinated by March 31. Therefore, in every facility, the follow-up time of unvaccinated residents was three weeks longer if the second dose was the Pfizer vaccine and four weeks longer if it was Moderna.

Moreover, follow-up of unvaccinated residents in some nursing homes started between December 18 and January 8. Not only was it earlier, but that was a period of high risk of infection just before the peak of the winter wave (see figure). All two-dose recipients were spared that early, high-risk exposure time. This bias—confounding by time trends in the background risk—has operated in other “real-world” studies from that time.

The bias is worse if the follow-up is delayed until 14 days after the second dose (to allow full immunity). In this case, follow-up of recipients of two doses began on January 22, ten days after the peak.

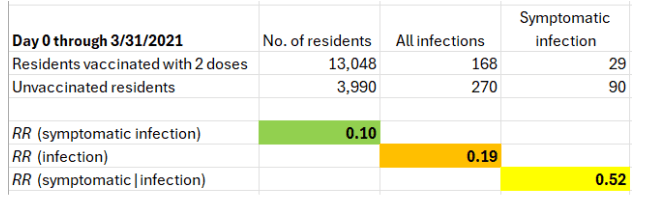

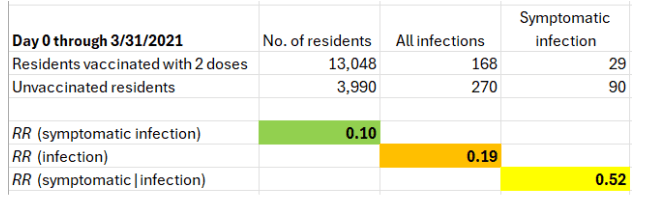

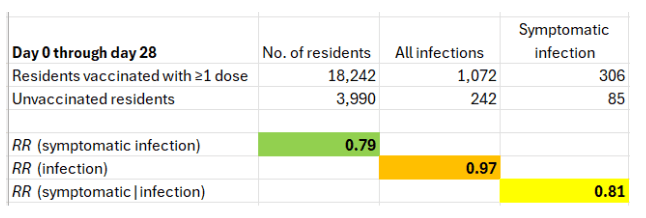

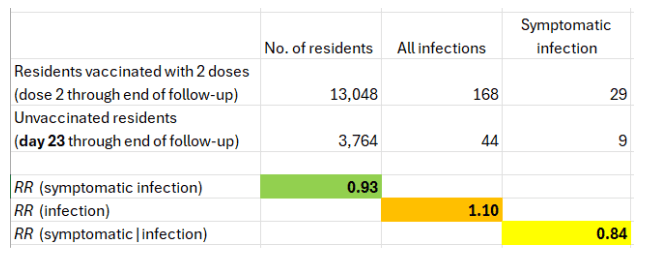

Using data from Table 1 in the letter, I computed three risk ratios (RR). In every facility, day 0 for the unvaccinated was 3-4 weeks earlier than day 0 for two-dose recipients.

The key number is the risk ratio of symptomatic infection. It is 0.1 (90% vaccine effectiveness). Surprisingly, the mRNA vaccines seem to have offered fragile residents of nursing homes with a weakened immune response almost the same level of protection that was reported for younger, healthy populations. Remarkable if true, or difficult to believe.

The risk ratio of symptomatic infection, which I questioned, is the product of two risk ratios: the risk ratio of infection (0.19) times the risk ratio of symptoms if infected (0.52).

The first estimate is unquestionably implausible. Upper respiratory infection is primarily prevented by secretory IgA antibodies on the nasal epithelium. That’s not the immune response to the spike protein that is circulating in the blood. The key mechanism of protection by an intramuscular injection cannot be mucosal immunity against infection (RR=0.19). Moreover, by now it is widely accepted that the mRNA vaccines do not prevent infection.

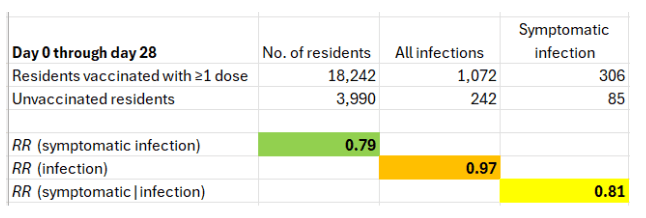

The results for the first dose are shown below. (Although the authors refer to the first 28 days after the first dose as “≥1 dose,” a second dose, if administered, was not expected to add benefit yet.)

Unlike the two-dose data, there is no confounding by time trends, and follow-up time is even. In every facility, follow-up of vaccinated residents and unvaccinated residents started on the day of the first vaccination clinic (or within a few days for some of the former).

What do we observe?

First, the risk ratio of symptomatic infection is 0.79, which is about 20% effectiveness. That’s closer to zero than to 50%, which was reported in the famous Pfizer trial between dose 1 and dose 2.

Second, with no confounding by time trends or uneven follow-up, we now observe the expected null effect on the risk of infection (RR~1; VE~0%). Obviously, effectiveness against infection could not have increased from 0% after the first dose to 80% after the second. That would be a biological miracle. Therefore, at least one component of the risk ratio of symptomatic infection after two doses is wrong.

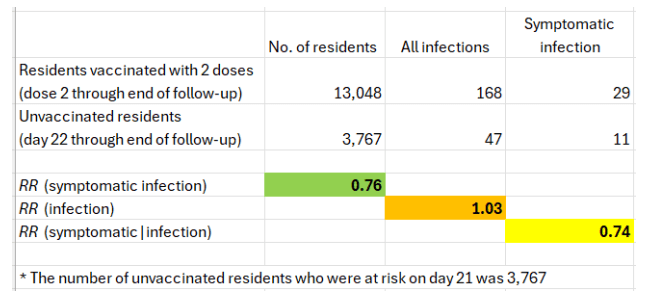

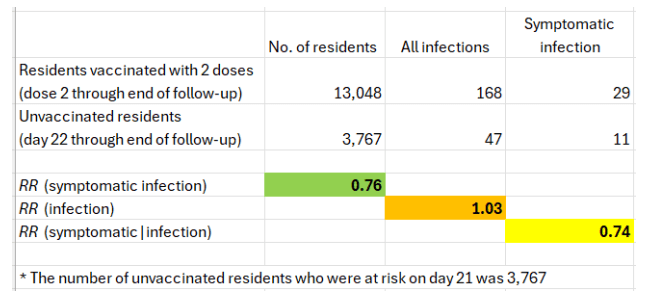

Finally, the uneven follow-up of two-dose recipients and the unvaccinated may be roughly corrected by considering cases in the latter that have occurred after three weeks. Based on Figure S1(C), between day 22 after the first vaccination clinic and the end of the follow-up, there were 47 cases of infection in unvaccinated residents, 11 of which were symptomatic.

The estimated risk ratios are shown below.

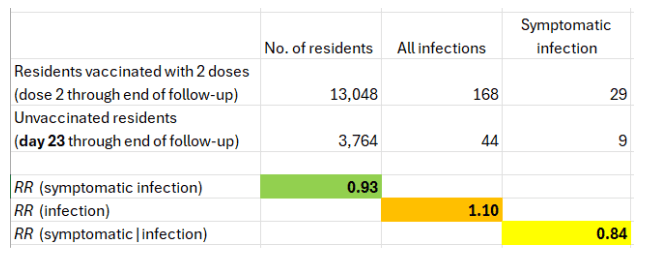

That’s a conservative approach because 21 days was the shortest interval for the second Pfizer vaccine, and the interval for Moderna was 28 days. A shift of one day (day 23 through the end of follow-up) changes the risk ratio of symptomatic infection from 0.76 to 0.93.

To summarize, this set of results does not demonstrate “real-world” effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines against symptomatic infection in a vulnerable nursing home population. Nor did the data from a study of Covid mortality of nursing home residents in Israel.

It is likely that the efforts to change the outcome of the most vulnerable segment of the population have been futile, if not worse. We are still waiting for a randomized trial of the mRNA vaccines in residents of nursing homes—with a mortality endpoint. A trial would be more ethical than continued approval of the mRNA vaccines. They are not risk-free injections, and there have been vaccine-related deaths.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.