Before properly starting this article, I’ll recall a phrase that almost everyone knows: “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as a farce.” The author is the German philosopher Karl Marx. It’s common for people to use variants of this phrase, which has become part of the popular imagination. After all, history tends to repeat itself cyclically.

And to complement it, I’ll quote another phrase. This one, unlike the first, is less known: “What experience and history teaches us is that people and governments have never learned anything from history.” This was said by Hegel, another famous German philosopher.

Why do I start by talking about history? Because before delving into the core of this article, which discusses the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s necessary to recall the previous pandemic: AIDS, a disease that terrified and devastated the world from the mid-1980s, resulting in the loss of about 40 million lives, according to UNAIDS official estimates.

To put this in perspective, World War II as a whole resulted in 70 million deaths. AIDS, therefore, as a significant event in human history, accounts for a little more than half the casualties of World War II.

AIDS in Cinema

Even though AIDS has caused more than half the deaths of World War II, in popular culture, the two narratives show a great imbalance in cultural productions. While there’s a vast array of movies, books, and documentaries that have been released—nearly 80 years after the war’s end—depicting the battles and the context leading to the armed conflicts, the story of AIDS, a much more recent event, has only a fraction of that attention.

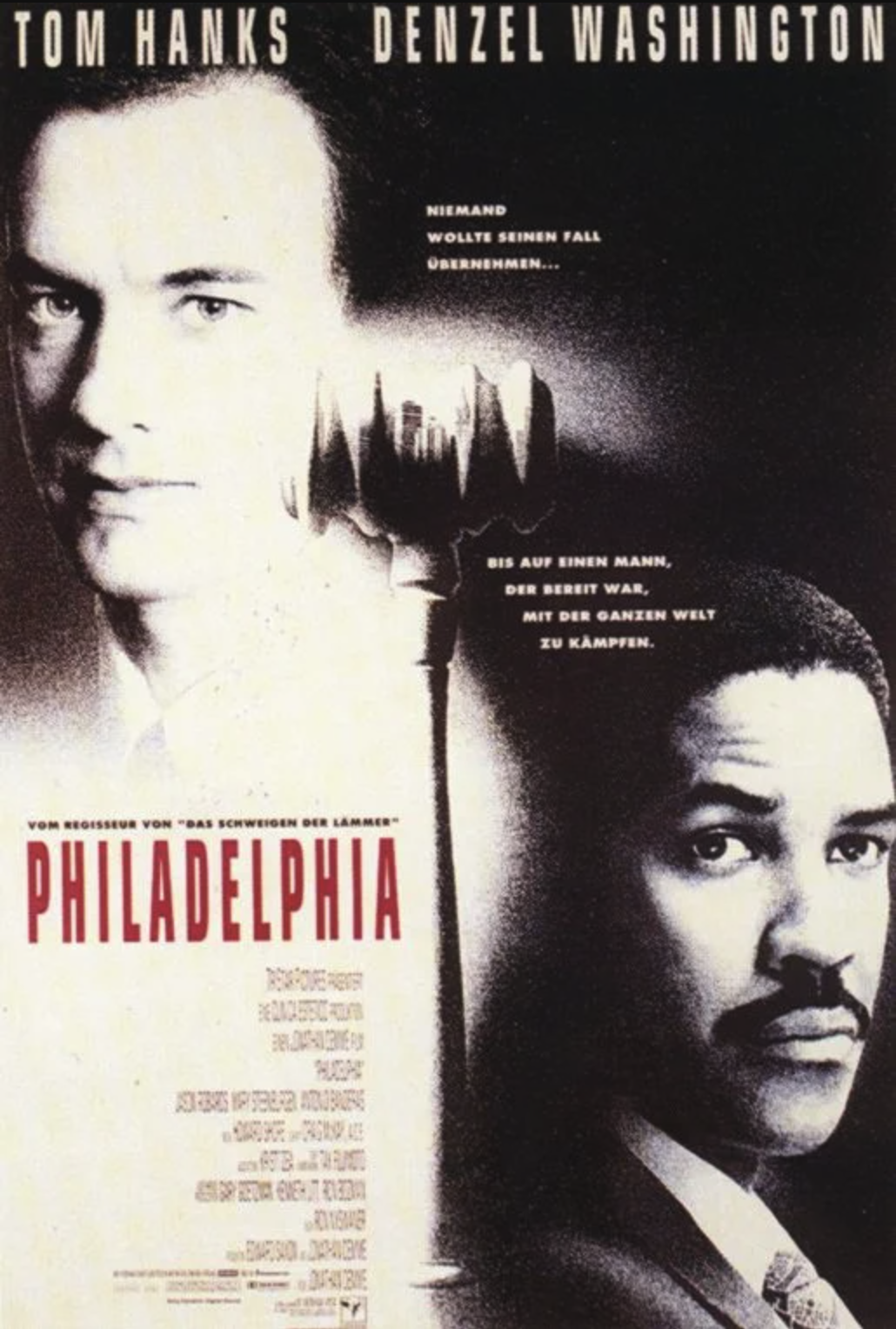

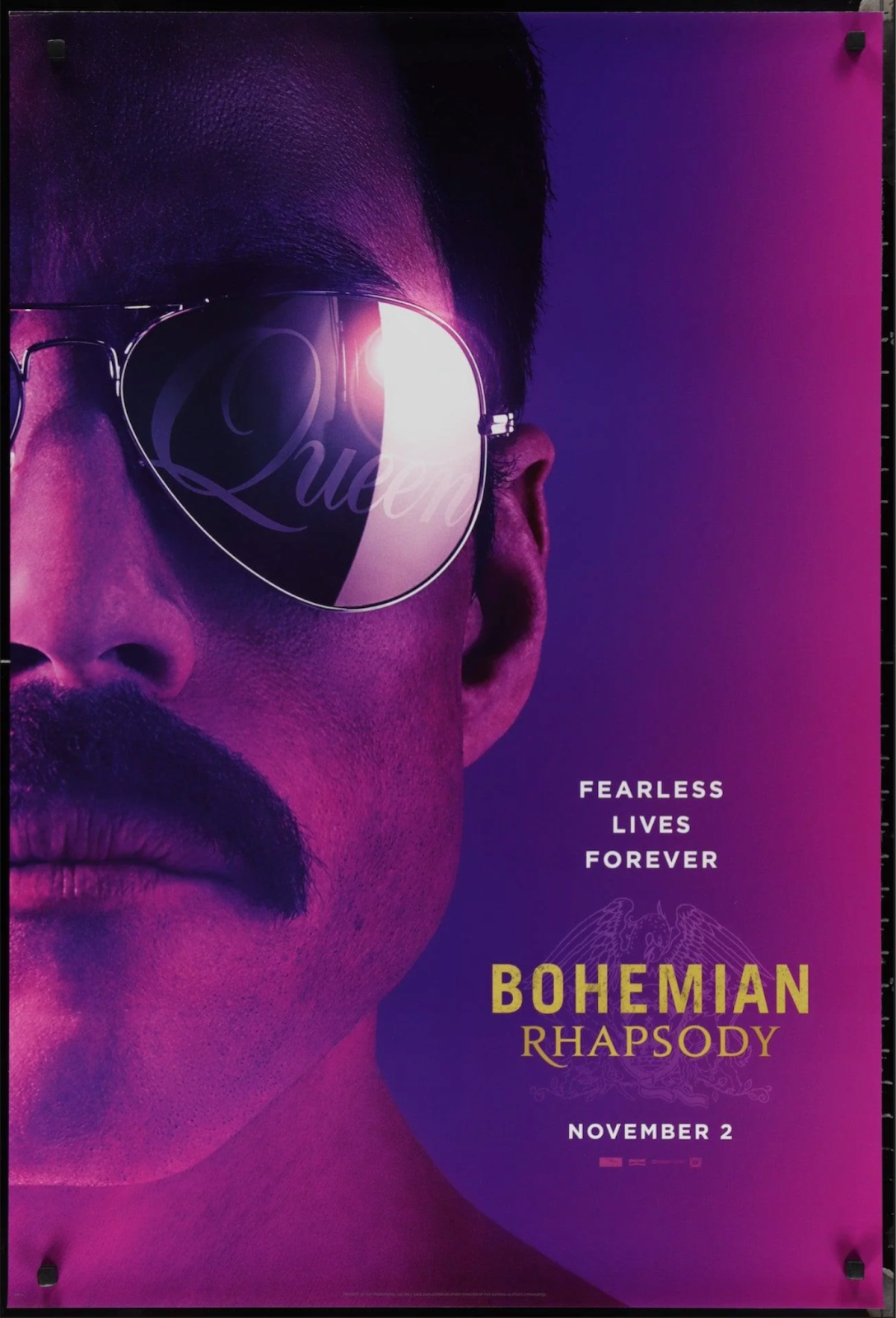

In any case, the smaller proportion of works about AIDS didn’t affect the quality of the productions. For movie enthusiasts, some films are truly memorable. In 1993, Tom Hanks won the Oscar for Best Actor for his role in the excellent film Philadelphia. More recently, in 2018, it was Rami Malek’s turn to take home the Academy Award for Best Actor. In Bohemian Rhapsody, Malek portrayed Freddie Mercury, the lead singer of the iconic British band Queen. His performance was truly impressive.

However, these two films focus only on the personal dramas of those affected by the disease. The scripts don’t delve into the great pettiness and hidden agendas that AIDS has sparked. In both films, the approach is different. In Philadelphia, we understand the prejudices faced by people with the virus. In Bohemian Rhapsody, we grasp the world’s grief over losing a major music star.

Roughly speaking, it’s like telling stories about people who drowned in the Titanic without explaining all the reasons that led to the collision with the iceberg, the accident that sent the ship to the bottom of the sea. These could be interesting stories, full of emotions, but they don’t get to the heart of the matter.

And Cinema Told the Greatest Story of AIDS

Today, a person with HIV has a life expectancy comparable to someone without the virus. But in the early 1980s, people with AIDS were dying like flies. Because of this, most people tend to believe that medicine takes a long time to understand the disease and develop an effective treatment. This is not true.

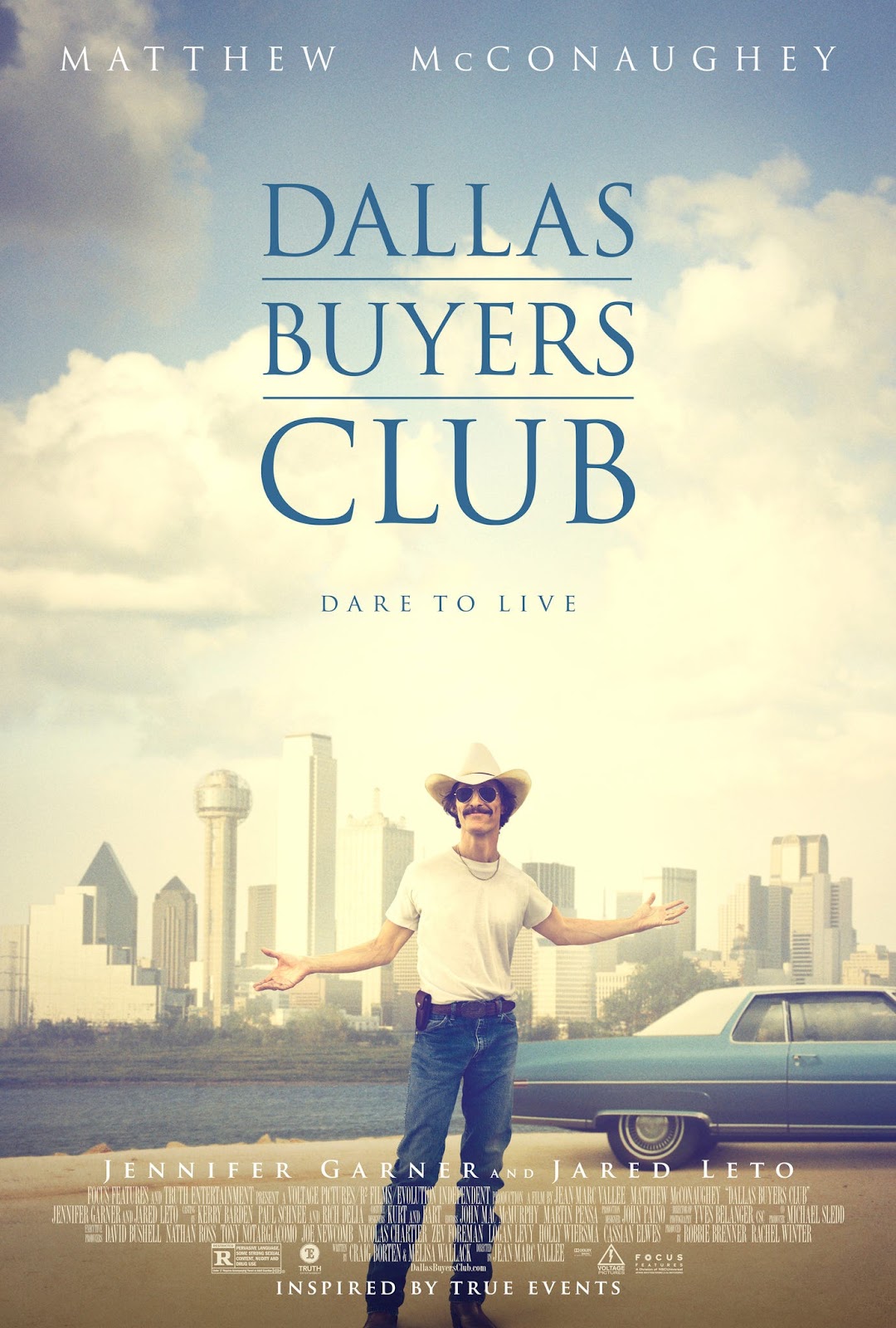

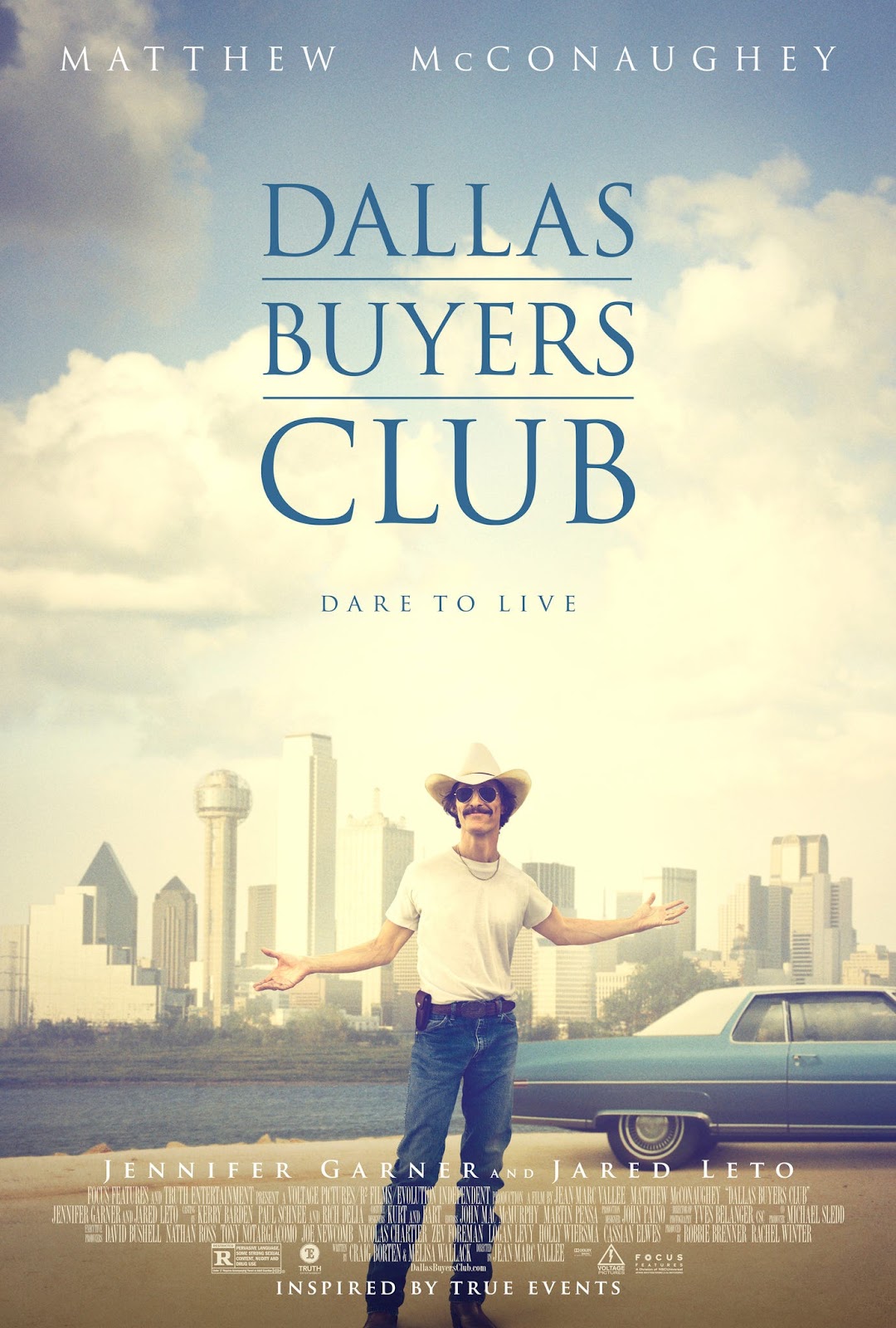

That’s where the most important story about AIDS lies: the disease had a highly effective treatment from the start, but everything was covered up by a conspiracy involving Big Pharma, doctors, scientists, medical societies, hospitals, and the US government. The motivation? A lot of money. They simply let millions die for profit. This story is masterfully told in the 2013 biographical film Dallas Buyers Club, winner of three Oscar statuettes, including Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor.

A summary of the plot? The film is set in the mid-1980s and tells the story of Ron Woodroof, a Texas electrician in the USA, who discovers he’s infected with AIDS. After the diagnosis, he finds out that the standard treatment in the United States, AZT, is highly toxic and ineffective. He then looks for alternatives and discovers a doctor who treats the disease with repurposed drugs.

At the beginning of the movie, when Ron learns about his illness, the doctor tells him he has only one month to live. In the end, Ron lived nine more years. And everyone treated with the “AIDS kit,” which Ron began selling illegally, also survived. Without effective treatment, the disease killed 100% of people within a few months. But everyone who took Ron Woodroof’s “AIDS kit” had a life expectancy close to normal.

And everyone who tried to treat the infected was persecuted, even by the police and all government authorities. They were the “science deniers” and “conspiracy theorists” of the time. Even some doctors lost their licenses for refusing to let people with AIDS die. Meanwhile, Big Pharma brought out drugs that only worsened the disease, but the profits were immense. AZT was the most expensive drug in history.

Every respectable film script has heroes and villains. Without them, there’s no story to tell. Dallas Buyers Club fulfills that requirement. And when people watch the film, there’s no doubt who the good guys and the bad guys are. The good guys were the ones who, despite being attacked and persecuted, drastically reduced the mortality rate of the disease.

From AIDS to Covid-19

Any possibility of treating Covid-19 with inexpensive, generic, and unpatented drugs, just like in the early days of AIDS, was dismissed as crazy talk, flat-earth theory, or conspiracy. After all, according to all mainstream media, it was all “proven to be ineffective.” No matter how many studies were published, they were always “without scientific evidence,” according to the media.

At this point, among the “experts” with a voice in the media, there began a tiresome discourse to obscure the truth, full of phrases like “scientific rigor,” “double-blind,” “impact factor” of scientific journals, and the argument that we should fully trust regulatory agencies.

However, no discourse can overshadow the results of frontline doctors who treated many Covid-19 patients with little or no deaths, echoing what we saw in Dallas Buyers Club. After all, if these doctors’ patients weren’t dying in large numbers during a pandemic that killed millions, they were doing something that worked.

Extra note: Strangely, scientific communicators didn’t label it “proven to be ineffective” when the expensive and patented drug Remdesivir was approved and endorsed by regulatory agencies for Covid-19—the approval was based on an April 2020 study that yielded no positive results. Atila Iamarino, Brazil’s most successful science communicator with over a million followers on X (formerly Twitter), celebrated the approval. “Great for reducing ICU pressure,” he wrote. In fact, the study showed 8.6% more deaths in the Remdesivir group than in the placebo group. At the end of the study, on day 28, 22 out of 158 in the drug group died, while 10 out of 78 in the placebo group died.

Conscience Relief

José Alencar, a doctor, professor, researcher, and digital influencer who defines himself as a “Defender of evidence-based medicine” and is the author of books in the field, positioned himself throughout the Covid-19 pandemic against treatments using generic, cheap, and unpatented drugs, often in an offensive manner. For him, this topic was only worth discussing on April Fool’s Day.

However, the results of frontline doctors fighting Covid-19, with overwhelming numbers that were easily understandable to both laypeople and specialists, still haunt those who vehemently opposed these treatments, especially those who mocked and contributed to the persecution of doctors who chose not to let patients die.

With this burden on his conscience, Alencar, now in 2024, seeking relief, made a very popular post on his Twitter account, where he has over 50,000 followers. In an educational way and using allegories, he explained the fundamentals of the article “The Mathematics of a Lady Tasting Tea,” by Ronald Fisher, one of the fathers of statistics.

In the fictional scenario, a young lady claimed she could tell, in a cup of tea with milk, whether the milk or the tea was added first. She asserted that the taste would be different depending on which was added first. Fisher’s article proposed that, with eight cups, the probability of guessing all correctly is 1.14%.

Based on this article, Alencar proposed another probability exercise:

1 – For example, if the doctor you follow on Instagram says he treated 100 people with a certain disease, and they all survived, what is the probability that this occurred by mere chance? Shall we use Fisher’s teachings?

2 – First, we need to know the fatality rate. Let’s say that, in its natural course, the disease kills 1% of those infected—1 out of every 100.

After calculations, we find that the probability of something as extreme as 0 deaths out of 100 (when the fatality rate is 1%) is 36%.

3 – So does that mean your favorite Instagram guru is claiming victory for something that could have been mere coincidence? Yes, my friend.

Alencar got the calculation right. In a disease with a 1% fatality rate, if a doctor treated 100 people, the chance that no one died is 36%. But is this the reality of Covid-19 and the reality of the doctors who decided to treat the disease with the best available evidence?

Frontline Results

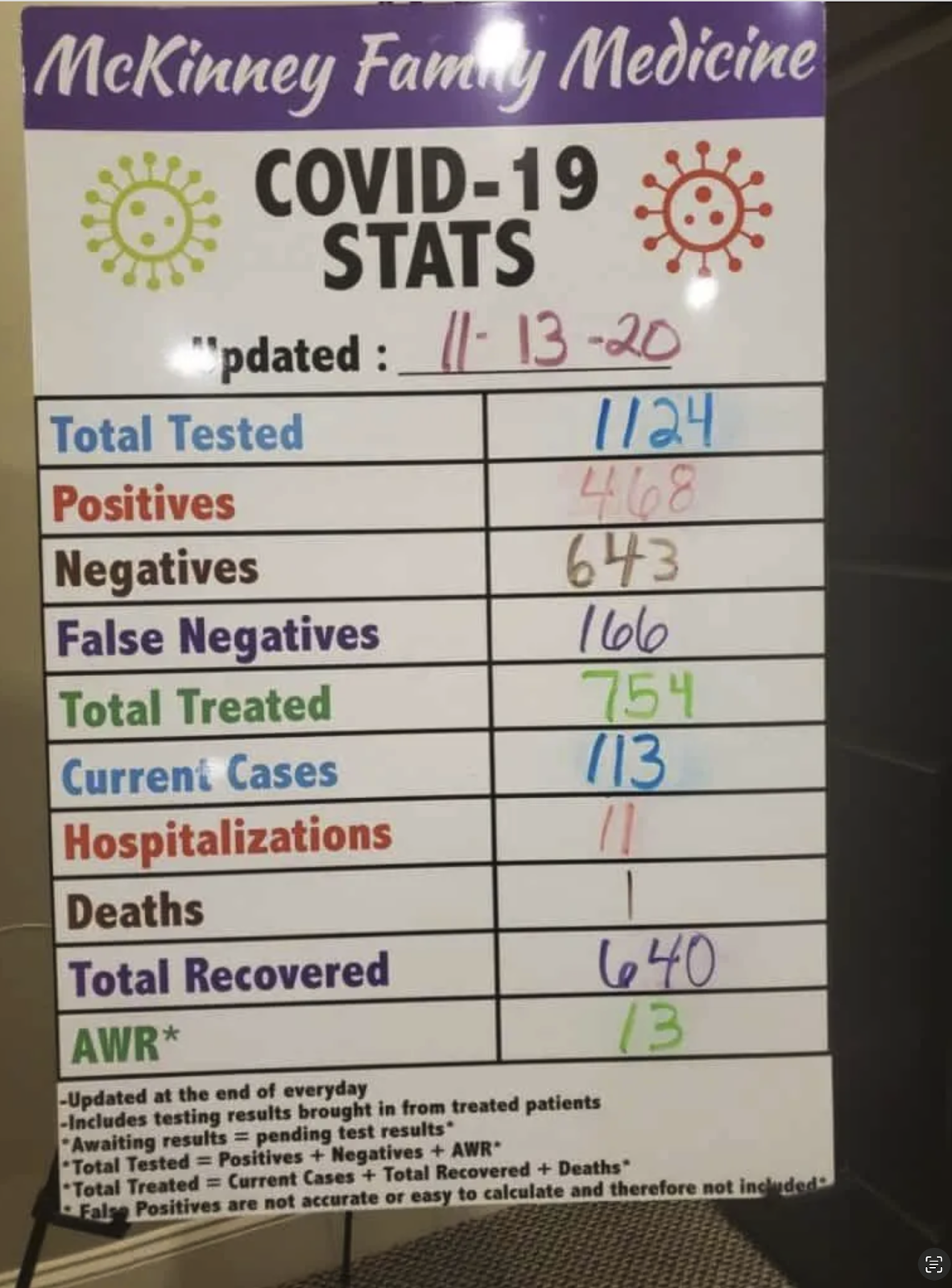

From the beginning of the pandemic, a US doctor, Brian Procter, decided to share his results live on Twitter. He set up a whiteboard in his office. With each update, he posted a photo of the whiteboard on his social media. This is the photo from a post when he had treated 754 patients with only a single death.

Dr. Procter understood the impact of his communication, similar to what Ron Woodroof did during the AIDS crisis. The people responsible for Twitter’s censorship also grasped the impact, to the extent that Dr. Procter lost his account on the social network.

Subsequently, Dr. Procter published a peer-reviewed study in the International Journal of Innovative Research in Medical Science, detailing the results of his treatment cocktail. In the end, he treated 869 Covid-19 patients, all over 50 years old or, if under 50, with at least one comorbidity. He deemed it unnecessary to treat those under 50 without comorbidities. Among the 869, only 20 needed hospitalization, and only two died.

Also from the US, using the same cocktail of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, among other drugs, Dr. George Fareed and Dr. Brian Tyson treated 3,962 patients within the first few days of symptoms. None of these early-stage patients died. Of the 413 patients who arrived after the initial stage of the disease, with more than five days of symptoms, the American duo had only three deaths.

In France, Dr. Didier Raoult, also using hydroxychloroquine as a base, treated 8,315 patients with symptoms lasting up to five days. Of these, only 214 needed hospitalization (2.6%), and only five died. Raoult and his team’s results were published in the peer-reviewed journal Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine.

In Brazil, Dr. Cadegiani has treated 3,711 patients since the beginning of the pandemic. Of these, there were only four hospitalizations, and none resulted in death. One hospitalization required intubation, but the patient survived, narrowly avoiding a fatal outcome.

In Peru, Dr. Roberto Alfonso Accinelli treated 1,265 patients, with seven reported deaths in his peer-reviewed study. In this case, among the 360 treated within three days of symptoms, no one died. Several other doctors who dared to treat patients, even while being persecuted like the doctors in Dallas Buyers Club, achieved similar results.

Here’s a list of outcomes from doctors and medical teams who used treatment cocktails against Covid-19. Many of these results were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Reality Versus Lying to Oneself

In Alencar’s comforting story, there were 100 patients with a disease that had a 1% fatality rate. According to his calculations, which are correct, there’s a 36% chance that no one would die with ineffective treatment in his hypothetical disease with a 1% fatality rate among 100 patients. So, in this case, there wouldn’t be a reason to claim success.

However, in Covid-19, the fatality rate was approximately 2% throughout the pandemic until the Omicron variant appeared at the end of 2021. This means that, on average, one person died for every 50 infected, not every 100. And we’re not talking about just 100 patients. Adding up all the results from the doctors I listed above, there were 18,525 people with the disease who sought treatment. And in total, 17 people died. This yields a fatality rate of 0.09%.

I’m not going to get into the exact fatality rate of Covid-19. I’m going to lower the fatality rate to below the minimum, and in an unrealistic way. In Brazil, we have 203 million inhabitants. According to the country’s official Covid-19 death count, 712,000 people died.

Let’s suppose that all Brazilians had Covid-19—which is not the reality, because many didn’t get the disease—and that everyone was treated and had the same 0.09% fatality rate as those mentioned earlier. In this case, total deaths would have stopped at just over 186,000. But 712,000 people died.

So, even with the most conservative (lower than the real) estimate of the fatality rate, more than half a million Brazilians would be alive today.

Layperson or specialist, when watching Dallas Buyers Club, you understand the effectiveness. And nobody is confused about who the heroes and villains are. Layperson or specialist, upon seeing the results of these doctors against Covid-19, understands the effectiveness because almost no one died. And I know who today’s heroes and villains are.

Shoddy Calculations for Applause and Comfort

Alencar had to distort reality to come up with math that gave him comfort. He lied to himself. And if he’s still doing this four years after the pandemic, it means the results of those who faced the disease haunt those who stood against them, aided the persecution, and even insulted those who dared to treat and bring results.

Leandro Tessler, a professor at Unicamp, one of Brazil’s largest public universities, who defines himself as a “science communicator,” found the comfort he was seeking in Alencar’s post. Throughout the pandemic, he took it upon himself, on behalf of the university, to classify what was true and what was false on social media. In doing so, he attacked everyone who dared to treat him. Tessler even celebrated the censorship of those who reported on studies and results.

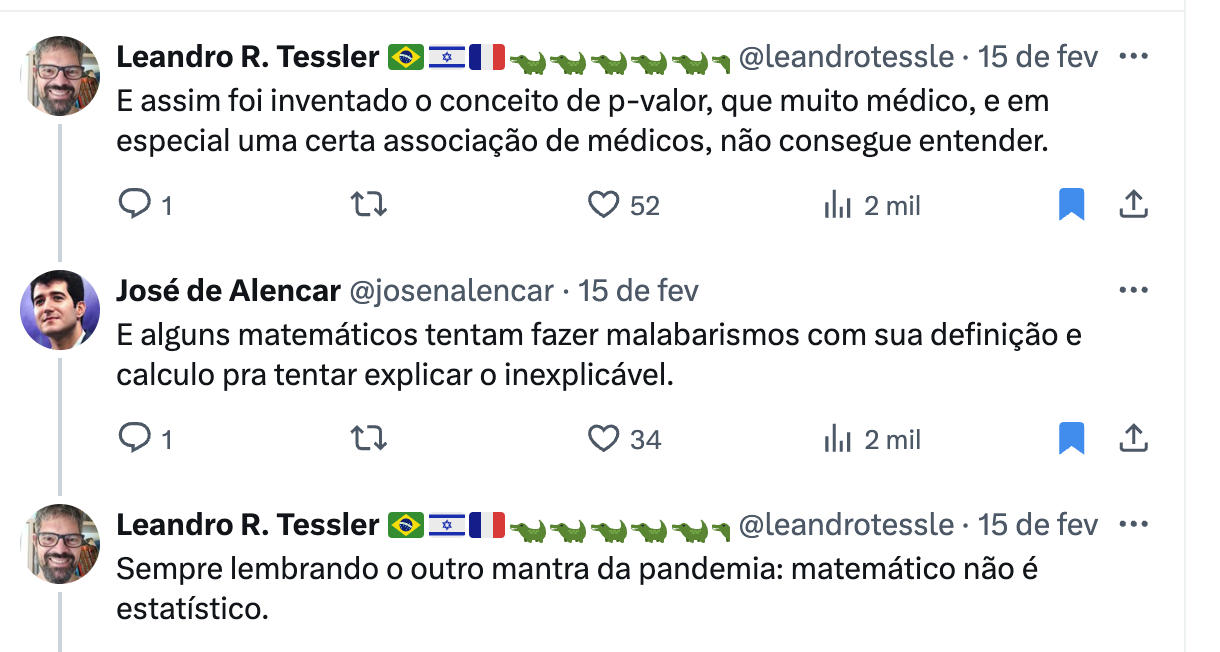

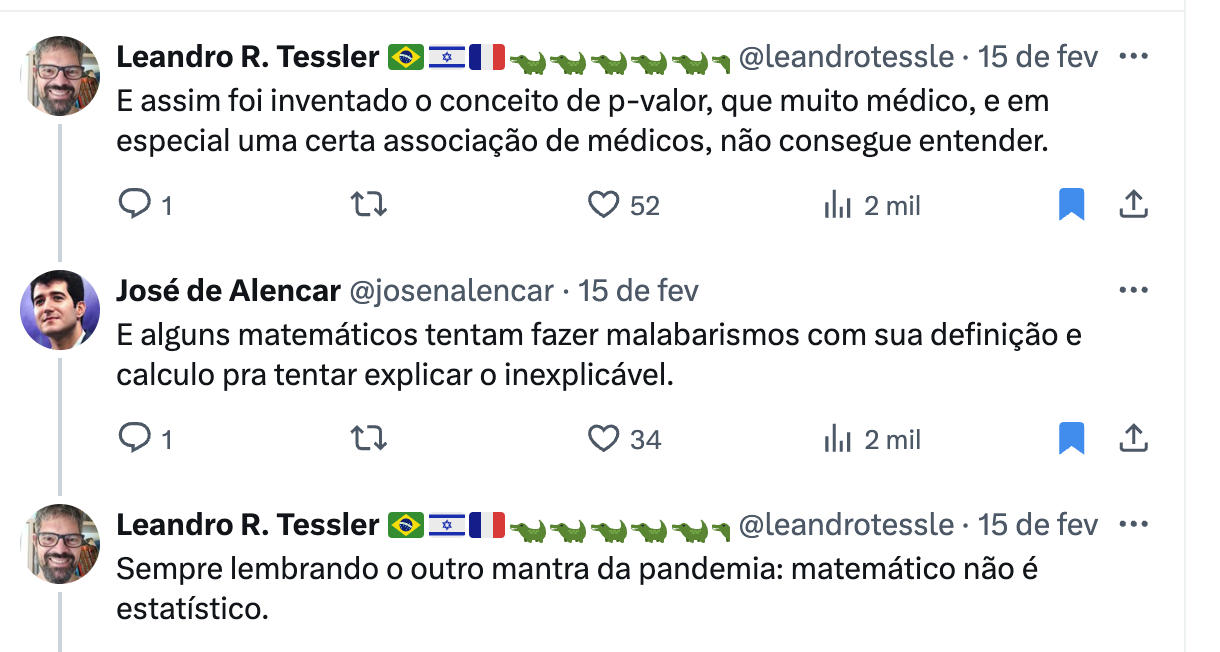

Tessler: And so, the concept of p-value was invented, which many doctors, especially a certain medical association, cannot seem to grasp.

Alencar: And some mathematicians try to perform gymnastics with its definition and calculation to explain the inexplicable.

Tessler: Always remember the other pandemic mantra: mathematicians aren’t statisticians.

Here, Tessler attacks the math professor from USP, Daniel Tausk, for his efforts to analyze and explain clinical studies to frontline doctors who wanted to understand all possible approaches to combat the disease, helping them in their search for the best scientific evidence.

Well, Marx and Hegel were right. History repeats itself, and people learn nothing from it. It must be hard to see the outcomes of those who treated Covid-19, then realize you’re on the wrong side of history when you look in the rearview mirror. They can’t go back; they can only move forward, deceiving themselves. There are no other options.

For everyone’s comfort, all that’s left is the creative math of academic circus artists.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.