To theorize about our existence is essential. Indeed it could be argued that to think and speak is, in the most basic sense, to impose abstract models upon the multiple and often confusing manifestations of life around us. Without mental models for understanding the things outside our heads we would in all likelihood become seized with fright, and rendered largely incapable of imposing our individual and collective wills upon the world in any meaningful fashion.

I advance the foregoing ideas, however, with an important caveat: that while theories are essential for initially impelling individual and collective energies toward the taking of meaningful actions, they completely lose their utility when those claiming to be guided by them refuse to revise the assumptions of these mental constructs in the light of emergent and empirically verifiable realities.

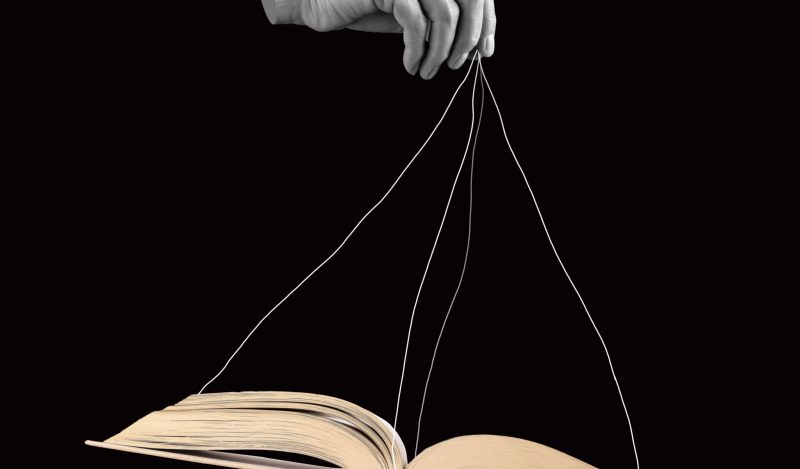

When this occurs, these once useful tools are transformed instantaneously into intellectual totems whose only function is to appropriate the energies and loyalties of those individuals who are either unwilling or unable to engage with complexity, and the demand for cognitive improvisation it constantly imposes upon us.

Over the last three years we have seen example after example of this mental ossification in our would-be intellectual classes. They bombarded the populace with empirically unproven models of their own making about many things connected with Covid. And when the vast majority of them proved completely at odds with observable reality, they simply doubled down in their propagation of them, and worse yet, stridently refused to entertain any substantive debate with those bearing contrasting arguments or data.

While the brazenness and magnitude of this abuse of modeling may be new, its presence in American life is anything but. Indeed, it could be argued that this country’s vast overseas empire could not have been founded and maintained without two academic disciplines whose production often tends quite heavily toward the creation of context-free and/or context-light models of vastly complex realities: Comparative Politics and International Relations.

As with nations and states, the fate of an empire depends heavily on the ability of its elites to generate and sell a compelling narrative of their society’s imagined community to the rank and file citizenry. But while in the case of the creation and maintenance of nations and states puts a premium on the evocation of positive values about the in-group, empires place much more value on the generation of dehumanizing portrayals of others, narratives that point to the “need” for these others to be reformed, altered, or eliminated by “our” obviously superior culture.

In other words, if you are going to convince young people to kill and maim folks in places thousands of miles from home, you must first convince them that their future victims are lacking in certain essential human qualities, a posture neatly summarized in a quip often tossed around by pro-empire partisans: “For those people, life is cheap.”

Key to this process of dehumanization is generating a “safe” observational distance between the members of the imperialist society and those “savages” that happen to inhabit spaces over or around the resources the imperialist society seeks to own. Why? Because getting too close to them, looking into their eyes, and listening to their stories in their own terms and in their own language might lead to unfortunate outbreaks of empathy in the imperial party, an eventuality that might fatally attenuate the imperial soldier’s drive to kill and pillage.

Much more effective, as Mary Louise Pratt suggests in her studies on European travel literature of the late 19th century—the heyday of the Western assault on “lesser” peoples in Africa—is to ply the citizens of the homeland with narratives characterized by “promontory views;” that is, views of the foreign land taken from “on high” that obviate or minimize enormous the potentially conscience-jarring presence of real human beings with real human pathos within the coveted territory.

These travel narratives, however, were but one prong of a multifaceted effort to distance the imperial citizenry from the messiness of their country’s overseas endeavors. Far more important in the long run has been the institution of Political Science and its disciplinary stepchildren Comparative Politics and International Relations, subject areas whose founding coincides more or less in time with the aforementioned late 19th and early 20th century European and North American pursuit of resources and political control in what some now call the Global South.

The central conceit of both of these disciplines is that if we adopt a distanced point that minimizes historic and cultural particularities of individual societies, and instead emphasize the seeming commonalities between them in the light of the present-day comportment of their political institutions, we can create analytical models that will allow the elite inhabitants of the metropole to predict future socio-political developments in these places with considerable accuracy. And that this, in turn, will allow those elite inhabitants of the metropole to develop to contain or alter these tendencies in ways that favor their own long-term interests.

To give just one example of this dynamic with which I happen to have a good deal of experience, this means having an English language “expert” who does not fluently read, speak, or write Catalan, Italian, or Spanish, and who thus cannot cross-check anything he says against basic in-culture sources, advance theories that seize upon some superficial similarities of the autonomist Lega Nord in Italy and the Catalan independence movement in Spain, and to conclude—in complete contradiction to available archival evidence—that the latter movement, like the former is and always has been firmly rooted in an authoritarian right-wing ethos.

These sages often do the same thing when speaking about the dynamics of identity issues within the Iberian Peninsula itself, making, for example, broad brush assumptions of similarity between nationalist movements Catalonia and the Basque Country, two phenomena with very distinct historical trajectories and tendencies.

When I have had to the opportunity to ask people making such statements whether they have actually read any of the founding documents of these movements written, say, by X or Y, they literally have no idea of who or what I’m talking about.

And yet, when a major Anglo-Saxon media wants an explainer on what is going on in such places they will inevitably call upon the monolingual modeler rather than the culture-drenched denizen of foreign streets and archives. The key reason for this is that the financial and institutional powers in the US, and increasingly Western Europe have worked to provide the modelers with an aura of clairvoyance and scientific rigor that they do not, in fact, have.

And why’s that?

Because they know such people will reliably supply the simplifying promontory views they need to justify their predatory policies.

I mean, why invite a real in-culture expert, (or heaven forbid an actual English-speaking native of the area) who will inevitably convey the nuances and complexities of the situation in place X or Y, when you can bring in a “prestigious” think-tank-funded modeler who will provide a much simpler and all-embracing view that can be much more easily sold to the rubes?

It would be bad enough if this were simply a media and academic reality. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case.

Though members of the US State Department have long been known—relative to the members of other diplomatic cadres—for the poverty of their linguistic and skills and foreign cultural knowledge, there were earnest attempts during the 60s and 70s to remediate this long-standing problem through, among other mechanisms, the development of area studies programs at US universities and within the State Department itself.

However, with the election of Ronald Reagan, with his pledge to develop a more muscular and unapologetic foreign policy, these efforts to develop more and better area specialists were greatly curtailed. The underlying premise for the change was the belief that as area specialists come to meet and know foreigners on their own cultural and linguistic terms, they will inevitably come to empathize with them and thus be less inclined to pursue US national interests with the requisite stridency and vigor, a transformation that reached its zenith a decade or so later when, as Bill Kristol proudly explained, most of the key Arabists at State and elsewhere were purged from the higher levels of Mideast policy making.

As a cursory review of the CVs of young and mid-career State Department officials today will quickly show, the new ideal version of the State Department employee is a graduate from an English-language social science discipline heavy on modeling approaches to reality (Poli-Sci, Comparative Politics, IR or the new one Security Studies) who, while he or she may have spent time in a foreign university or two while in college or grad school usually in an English language classroom environment has, at best, a halting command of another foreign language, and hence a very limited ability to cross-check the theories fed to him or her during their education against the “street” realities in the country of their posting.

I recently had the occasion to observe the new prototype of an American diplomat up close and personal at a ceremonial meeting between the foreign minister of an important EU member state country and the Chargé d’Affaires of the US Embassy in that country.

While the first spoke in warm and conventional diplomatic boilerplate about the history and shared values of our two countries, the second, a guest in the country, spoke with a control of the native language just slightly beyond the level of “Me Tarzan, You Jane” not mostly about the historic ties between the two nations, but the current US administration’s obsessions with global health policy, LGBTQ+ rights, and the urgent need to smite those internal and external groups in the US and Europe who disagree with certain elements of the International Rules-Based Order.

Talk about developing and deploying government agents who are locked into the world of promontory views!

It would all be somewhat comical were it not for the fact that in a fast-changing geopolitical environment the US and its European client states are in dire need of gaining a more nuanced understanding of those countries their foreign policy elites run around constantly portraying as our implacable enemies.

Can one really practice diplomacy when one party believes it has most of the answers and in many, many cases literally cannot enter into the linguistic and cultural world of the other?

The answer is clearly no.

And this is one of the big reasons the US, and increasingly the EU, no longer effectively “do” diplomacy, but rather issue an endless series of demands to our designated enemies.

At this point, some of you might ask what any of this has to do with the Covid crisis. I would suggest quite a lot; that is, if you accept what numerous historians have suggested over the years: that in the waning years of their existence, all empires eventually bring the repressive tools they have used on foreign others to bear upon their home-borne populations.

During Covid, our elites established cadres of “experts” in institutional “promontories” from whence it was difficult if not impossible for them to recognize, never mind respect and respond to, the variegated beliefs and social realities of the general population.

Fueled by fanciful theories of their own making, which were turned by dint of repetition within their own endogamic sub-cultures into unassailable “truths” that could not , and would not admit dissonance or reply, they demanded absolute obedience from the common people.

And when as the dismal empirical results of their policies became apparent and they began to “lose” the crowd they thought was theirs to control and guide in perpetuity, the only “explanation” they, like their US diplomatic counterparts of today, could come up with was that these lesser people were just too dumb to understand what was truly “good for them.” Which of course is an excellent way—how convenient—of justifying the need for still more nudging, coercion and censorship.

The only way this cycle of human degradation can be stopped is if we all come down from our beloved reconnaissance towers and engage with each and every person the way they are, and not as we think we “need,” and have a “right” for them to be.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.