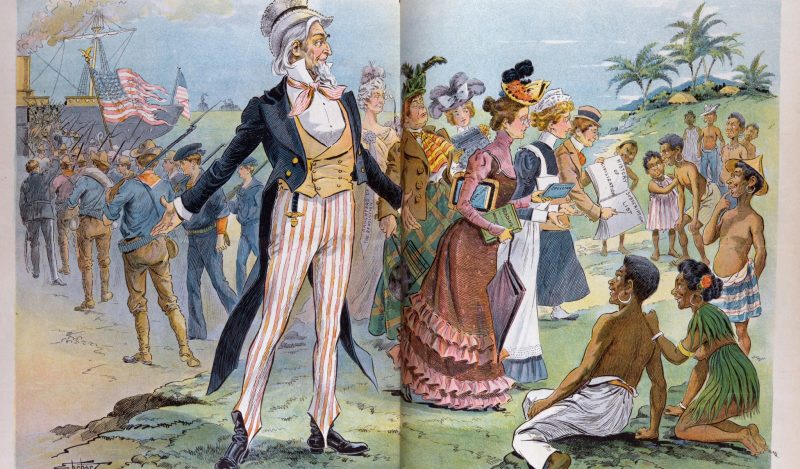

One of the key drivers of modernity is the belief that human beings are at their core empirically-minded creatures who, if left to develop this innate disposition to its fullest, will in time uncover and explain all of the world’s many mysteries.

It is a very compelling idea, one that has no doubt greatly contributed to energizing what is sometimes referred to as the social and material “march of progress.”

As an epistemic system, however, it is also plagued by a grave foundational problem: the supposition that an acculturated human being can and will assess the reality around him with virgin or unbiased eyes.

As José Ortega y Gasset makes clear in his masterful short essay “Heart and Head” no human being can ever do this.

“In any landscape, in any precinct where we open our eyes, the number of visible things is practically infinite, but in any given moment we can only see a very small number of them. The line of sight must fixate upon a small group of objects and deviate from the rest, effectively neglecting those other things. In other words, we cannot see one thing without ceasing to see others, without temporarily blinding ourselves to them. To see this thing means unseeing that one, in the same way that hearing one sound means unhearing others…. To see it is not enough that there exist, on one side, our organs of sight, and the other, the visible object situated, as always, between other equally visible things. Rather we must lead the pupil toward this object while withholding it from the others. To see, in short, it is necessary to focus. But to focus is precisely to seek something before seeing it, it is a sort of pre-see before the see. It thus seems that every vision supposes the existence of a pre-vision, which is not the product of either the pupil or the object, but rather another, pre-existing faculty charged with directing the eyes and exploring the surroundings, a thing called attention.”

In other words, human perceptions in a given moment are always mediated by previous and often quite personal cognitive, vital and sensorial experiences, and as a result, can never begin to approach the levels of neutrality or breadth of focus that we humans are presumed to be capable of having as participants in the empiricist paradigm of modernity.

Ortega thus suggests that we should—while never abandoning the search for enveloping truths—always retain a consciousness of the fact that many if not most descriptions proffered to us as exemplars of reality writ large are symbolic placeholders, or proxies, for the integral reality of the phenomenon in question.

I may be wrong, but it seems that few policy-makers, and more depressingly still, few physicians today ever think about the Spanish philosopher’s advice about the need to constantly engage in what Pierre Bourdieu would come to call “critical reflexivity;” that is, the ability to honestly assess the inevitable shortcomings and blind spots located within the phenomenological frame(s) governing their daily labors.

In fact, we see much the opposite: a growing tendency among both political and scientific insiders, and from there, the general public to both naively presume the panoptic nature of the scientific gaze, and to imbue self-evidently partial or even purely theoretical “proofs” with the same evidentiary weight as results obtained in much more broadly designed trials with significant real-world outcomes.

Does this sound confusing? Perhaps an example can help.

The ostensible purpose of going to college is to get educated, which is to say, to submit one’s self to a series of rigorous exercises that expand the contours and capabilities of the mind.

When watching the commercial enterprise colloquially known as college sports on TV we are frequently told of the wonderfully high graduation rates achieved by certain coaches at certain universities. The announcers speak of these wonderful graduation rates to underscore the idea that the athletes you see on your screen are studying and getting educated, and thus enhancing the stated core goal of the University.

In this context, then, we could say that the graduation rate is serving as a proxy for the idea that a whole lot of education is taking place among the athletes at those institutions.

But is that necessarily so? Is it not equally possible that the institution, aware of the enormous financial benefits that a powerful athletic team can bring to it, might set up graduation processes for athletes that only very marginally touch on activities that might roundly be recognized as educational? If this is the case, (and it seems to be precisely so in more than a few instances) then we would have to say that an athletic program’s graduation rate is a mostly useless metric for measuring real educational progress.

So, why do they continue to harp on such measurements?

Because they know most people—thanks in large part to the grave deficiencies of our educational system—have never been forced to ponder the problem of perception and how quite powerful forces are constantly creating and organizing mental structures, or epistemologies, designed to mediate between us and the vastness of reality, mediations designed to direct our attentions toward perceptions and interpretations that are invariably amenable to the interests of those very same powerful entities.

Indeed, one of the more common of these elite-imposed “suggestions” is precisely the idea that there is no one or any group of people imposing frames of interpretation upon the common people; that is, that we are always and everywhere addressing ourselves to the world with a virgin gaze.

Like large revenue-producing college athletic programs, Big Pharma is deeply aware of how little thought most citizens, and sadly it seems, most medical professionals give to how “facts” and notions of “reality” enter into their field of consciousness. And they play mercilessly upon this widespread epistemological illiteracy.

Take the PCR test.

Since the dawn of western medicine, medical diagnostics has been driven by symptomatology; that is, by having a physician cast his experienced eyes upon the physical manifestations of sickness in the patient. No symptoms, no diagnosis. No diagnosis, no treatment.

But what if you are the owner of a business that sells treatments and wants to expand its market share? Or a government leader, who might want to sow panic and division in a population so as to better control them?

Might it not be in each of their interests to generate a proxy of illness, one that would greatly inflate the numbers of those considered “sick” or “dangerous” and sell it to the population as being as grave and important as the real thing?

This is exactly what was done with the known-to-be-wildly-inaccurate-toward generating-false-positives PCR tests.

We see a very similar approach in the measurement of vaccine effectiveness. The only truly useful measurements of vaccine effectiveness are whether a) they stop transmission and thus bring an epidemic to an end b) lead to a decrease of overall sickness and mortality.

But what if a company had invested billions of dollars in the development of a vaccine that could do neither of these things?

Well, you simply develop proxy measurements, such as the rise in antibody levels in injected trial subjects—results that may or may not have a proven causal relation with the above-mentioned real measurements of effectiveness—and present them as being flawless indicators of success in disease minimization and eradication. This was, it appears, what was done in the FDA’s recent scandalous decision to approve the MRNA vaccines for administration to newborns and toddlers.

We have been told ad nauseam that lowering cholesterol is per se a good thing. But what if, as Malcolm Kendrick and others have argued, the line of causality between elevated cholesterol and serious cardiac illness and cardiac deaths—arguably one of the most complex and multifactorial maladies a human being can suffer—is not nearly as clear as we have been led to believe?

Then we’d have another case of a proxy indicator—whose promotion not coincidentally enriches pharmaceutical companies greatly—being presented to us as a simple key to resolving an often inscrutably complex problem. And all this doesn’t take into account the often considerable side effects that have been shown to accompany the use of statins.

And what about blood pressure and blood pressure medications? Let’s assume you are someone who carefully and frequently monitors their blood pressure at home to insure that it remains within normal limits, but finds that when you go to the doctor—where anxiety is always present for many patients and where the prescribed procedures about how to take blood pressure are routinely violated by the hurried office employees—your reading is considerably higher?

Despite the fact that “white coat syndrome” has been well acknowledged in the scientific literature, the patient is often put in the position of having to defend their voluminous record of normal readings at home against the one-time, or every six month, reading taken in the artificial setting of the doctor’s office, with all that this implies in terms having to stand up to a doctor—talk about generating anxiety!—who is usually all too ready to use this obvious proxy indicator as a reason to commit the patient to a lifetime of antihypertensive medication.

Once you start examining things in this way, the examples are nearly endless.

The elites’ ability to flood our consciousness with fragmentary and undigested information has increased exponentially. And they are well aware of, and quite satisfied by, the sense of disorientation this information overload causes in the majority of citizens. Why? Because they know that a disoriented or overwhelmed person is much more likely to grasp at simplistic “solutions” when they are directed this way.

“Every religion is true one way or another,” writes Joseph Campbell. “It is true when understood metaphorically. But when it gets stuck to its own metaphors, interpreting them as facts, then you are in trouble.”

If we are to regain our rightful protagonism as citizens of a republic we must closely study the mechanics of these processes, starting, in the particular case of public health policy, by addressing the serial abuse of flimsy proxy “evidence” in matters of grave personal and public importance.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.