In April 2020, while most of the world was in strict lockdown, the New York Times published The Untold Story of the Birth of Social Distancing, reassuring readers that this concept of “social distancing” had a scientific history.

Of course, this was nonsense. Western nations hadn’t merely implemented voluntary social distancing, they’d imposed lockdowns: Shutting businesses and community spaces with the force of law. These lockdowns were unprecedented in the western world and weren’t part of any democratic country’s pandemic plan prior to Xi Jinping’s lockdown of Wuhan. They failed meaningfully to slow the spread of Covid and led to the deaths of tens of thousands of young people in every country in which they were tried.

But according to the Times, the science of “social distancing” all began in 2005, when Richard Hatchett and Carter Mecher were enlisted by the Bush administration to think of ways to combat a pandemic. Hatchett and Mecher were then inspired by a 2006 science fair project by the 14-year-old daughter of their friend Robert Glass on closing schools to prevent contagion.

Hatchett, Mecher, and their UK colleague Neil Ferguson then did studies portending to show that similar closures had led to better results in St. Louis than in Philadelphia during the 1918 Spanish flu. Armed with these studies, they gave this concept of community closures, which had “been around for centuries,” the new name of measures to increase “social distance” and pushed it through the federal bureaucracy: “In February 2007, the CDC made their approach—bureaucratically called Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, or NPIs—official US policy.”

In 2021, celebrity author Michael Lewis wrote The Premonition, a 240-page book that was essentially an extended version of the New York Times article, lionizing Hatchett and Mecher as heroes and going into meticulous detail on how a 14-year-old’s science project became a federal policy affecting hundreds of millions of lives. This effectively became the official story of the birth of social distancing.

This story had the benefit of being dumb enough to be believable. Intelligent people often live by the heuristic “never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.” Thus, for those who realized the strict lockdowns of 2020 had actually been a catastrophe, the story that all this ruin had been brought about as a result of their government’s implementing sweeping mandates based on a 14-year-old’s science project was so dumb that it had to be true. That’s our gub’ment.

The strict lockdowns of 2020 were similar enough to the voluntary social distancing measures entertained in pandemic plans, so the story went, that their implementation could be forgiven as a mistake. People were panicked, and that hysteria had led them to mistakenly turn the voluntary social distancing measures in their pandemic plans—which were legitimate “science”—into mandates, which were not.

There’s just one problem. The science of “social distancing” may not have been so legitimate after all.

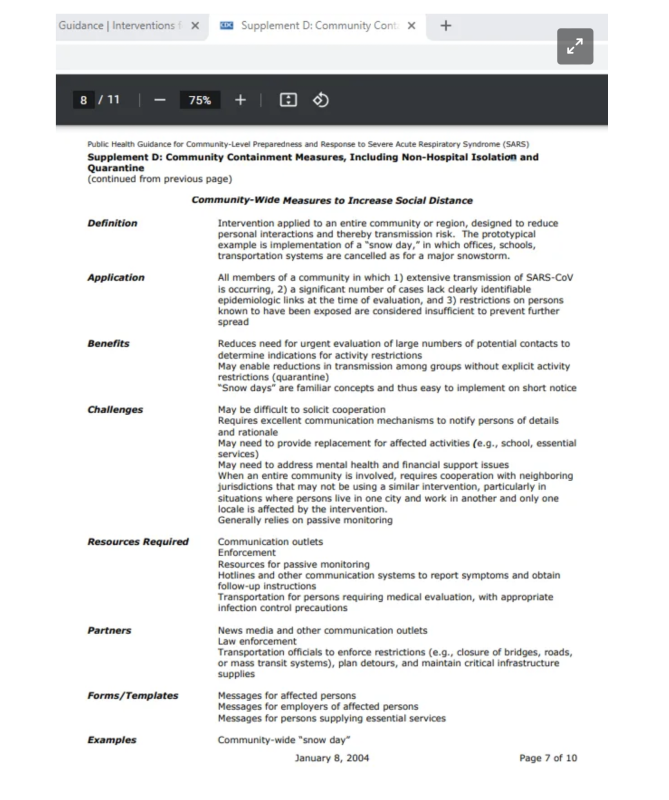

As it turns out, “community-wide measures to increase social distance” had already been promulgated into policy by both the CDC and the World Health Organization in early 2004. Thus, the official story of the birth of social distancing based on a 14-year-old’s science fair project falls apart entirely and appears to be nothing more than an elaborate cover story. In fact, these 2004 “community-wide measures to increase social distance” had been lifted straight from the closures imposed in China in response to SARS in 2003, in accordance with the ancient Chinese policy of lockdown (封锁).

The History of Lockdown and Herd Immunity

The concept of “lockdown,” or the mandatory closure of private and public spaces to limit potential human contact during a perceived outbreak, dates back to ancient times in China. This policy of lockdown is distinct from “quarantine,” which is the confinement of those who are ill.

After the Chinese Communist Party took power in China in 1949, this ancient concept of “lockdown” was effectively grandfathered into CCP policy. For example, one CCP document from the year 2000 contains very detailed instructions on the implementation of lockdown (封锁) in response to “an animal disease that seriously endangers human and animal health.” Another CCP document from 2002 recommends lockdown (封锁) in the case of avian influenza. The CCP also imposed lockdown measures in response to SARS in 2003.

That the CCP would continue this ancient policy is not surprising. As George Orwell famously captured in Animal Farm, the transition to communism was, for the most part, a continuation of the old feudal system with propaganda that was more appealing to 20th-century audiences. New pigs, same as the old pigs.

This concept of lockdown has precursors in other ancient civilizations as well, including in Europe. Various versions of lockdown were recorded during the Great Plague of London in the 1660s, during various medieval plagues in Italy, throughout Europe during the Black Death in the 14th century, and in countless other instances as well.

The results in each case were, of course, absolutely awful—the Black Death claimed over a third of Europe’s population despite all these lockdowns. Yet you may be familiar with these historical examples from the broad campaign of pro-lockdown propaganda to which we were exposed during peak Covid lockdown in spring 2020, in which these medieval examples were nearly always touted as having been on “the right side of science”—the ludicrous logic being that since medieval governments had ordered what modern governments were now ordering, then they must have been right, despite the countless decades of modern scientific evidence to the contrary.

For this reason, the New York Times and other major media outlets touted the lockdowns of 2020, all too accurately, as the return of a “medieval” policy.

The pervasiveness of lockdown across ancient and medieval civilizations is likewise not surprising, as the policy is innately appealing to the primitive mind ignorant of the complex and sometimes counterintuitive dynamics of epidemiology in interconnected societies. As with all effective propaganda, this innate appeal to the primitive mind is what gives lockdown propaganda such immense psychological power.

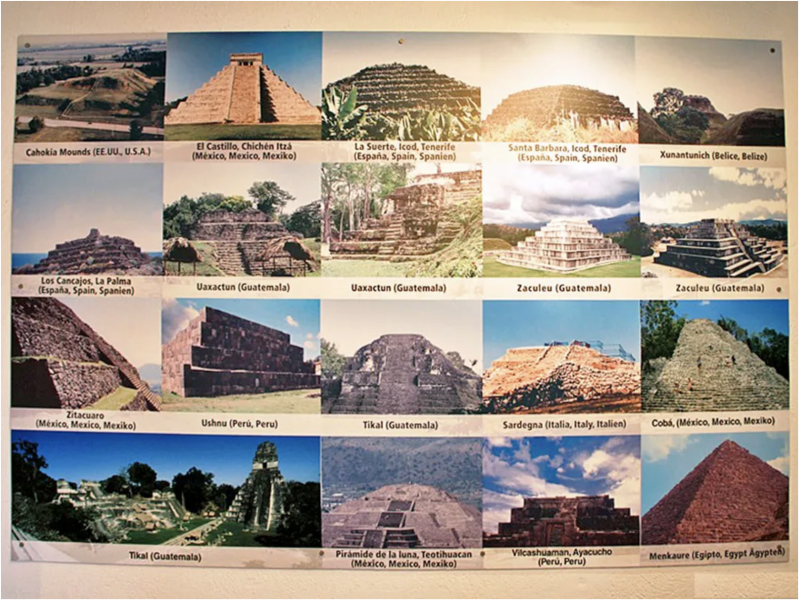

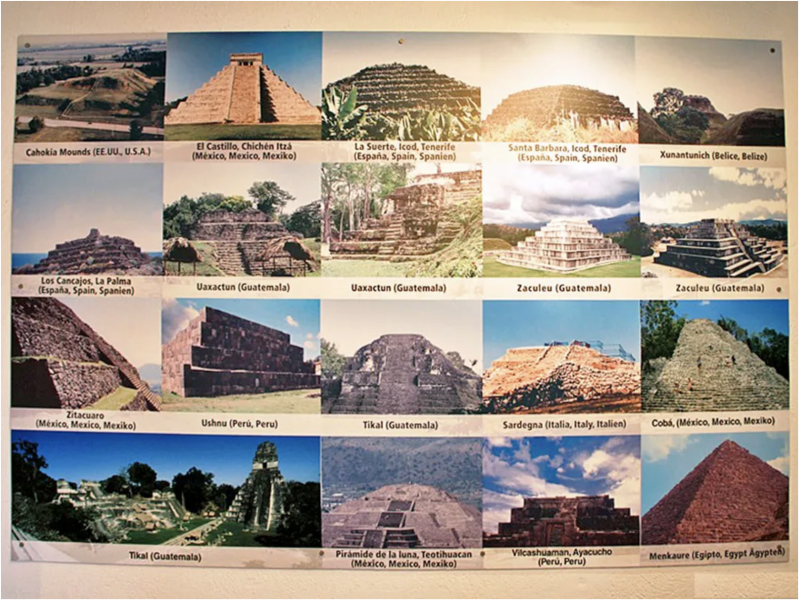

This phenomenon by which a civilization must transcend concepts that are innately appealing to the primitive mind can be observed across many fields. For example, the peoples of each cradle of civilization from the Americas to Asia at various times constructed giant pyramids, despite having had no contact with one another. Why pyramids? For the same reason children build pyramids at the beach: A pyramid is a big, strong structure that anyone can understand.

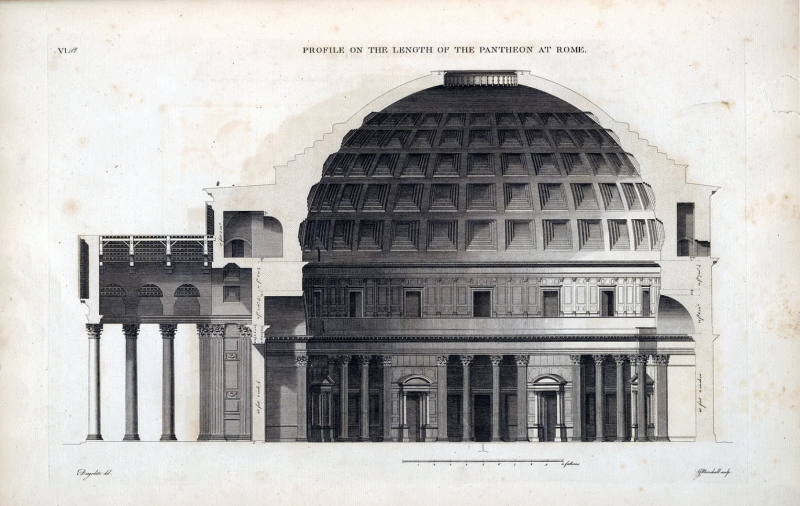

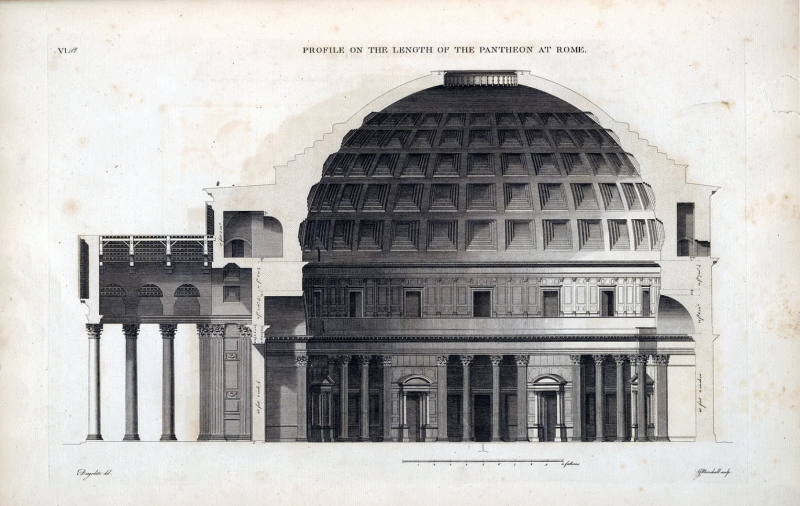

Of course, we now understand the pyramid to be a simple, inefficient structure, far inferior in both strength and utility to modern, arch-based structures. Yet it was only through countless centuries of careful study, intense focus, and attention to the brightest mathematical minds that the arch came to be widely accepted in the field of architecture.

The type of civilizational reverse-Enlightenment that we experienced during the response to Covid is also not altogether new. For example, after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Roman Pantheon was closed for centuries. The scholars of the early Middle Ages could not make sense of how such a giant arch-based structure could possibly remain standing, and therefore concluded that it could only be the result of witchcraft. QED. The Pantheon was opened only periodically to high-level members of the clergy, and even then only for the limited purpose of exorcising evil spirits.

Nor, sadly, is this type of reverse-Enlightenment always a random, transparent, or peaceful process. In some sense, the major wars of the 20th century can be viewed as conflicts by leaders who represented primitive, absolutist systems under the new branding of “fascism” and “communism” in an attempt by those primitive systems to reclaim power from more complex modern institutional republics.

Across many fields, the progress of human civilization can often be attributed to the mainstream acceptance of complex and often counterintuitive ideas, and nowhere was this more clear than in the fields of epidemiology and public health throughout the 20th century.

For centuries, scientists had observed the deleterious social, economic, and health effects of lockdowns and quarantines and wondered when and under what circumstances these measures were actually beneficial. This question came to especial prominence during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, after which a broad consensus formed that masks and lockdown measures had been counterproductive. As Michael Lewis relates in The Premonition:

A powerful conventional wisdom held that there was only one effective strategy: isolate the ill, and hustle to create and distribute vaccines and antiviral drugs; that other ideas, including social interventions to keep people physically farther apart from each other, had been tried back in 1918 and hadn’t worked. America’s leading disease experts—the people inside the CDC, and elsewhere in the Department of Health and Human Services —agreed on this point.

It was with this wisdom in mind that early 20th-century epidemiologists began to take a closer look at how diseases interact with immune systems—not just at the individual level, but within entire populations. Among them was A.W. Hedrich, who in the 1930s made the incredible observation that after enough healthy individuals within a given population contracted and became immune to a pathogen, the number of new infections fell dramatically, even among those who were still susceptible, as the pathogen ran out of hosts. This groundbreaking concept was carefully studied and documented over the coming decades and became known as “herd immunity.”

The principle was elegantly counterintuitive, and could best be summarized as “slow down before you hurt yourself.” Because epidemics would inevitably end through herd immunity, the role of public health should be limited to educating the public about proper hygiene, protecting the elderly and vulnerable, identifying the most effective treatment and vaccination protocols, and resisting mass hysteria and popular pressure for closures and other illiberal measures that were destructive and counterproductive.

Herd immunity became a central principle of modern epidemiology and public health planning, and it was applied broadly across the western world even during the worst epidemics of the 20th century, such as during the 1957 Asian flu and, even more famously, during the Hong Kong flu of 1968-69, in which Woodstock took place.

In each case, the results were extremely positive—so much so that today, few attendees of Woodstock have any idea that they spent the summer of ‘69 partying during an epidemic that was arguably more deadly than Covid. Though far more people ultimately died during Covid, these excess deaths have been vastly skewed toward age groups at little risk from the virus, indicating that they’ve predominantly been caused by the response to Covid rather than the virus itself.

One of the great advocates of herd immunity as a central principle of western epidemiological planning was Donald A. Henderson, the man widely credited with eradicating smallpox. Henderson was a revered, almost Gandalf-like figure in the field of public health.

As Lewis describes: “[T]he legendary D.A. Henderson … was just then the only human being walking the planet who might challenge Foege for the title of greatest living disease battlefield commander.” Henderson was an outspoken critic of the new fascination with “social distancing” and, along with PCR inventor Kary Mullis, was one of the few individuals who may have singlehandedly stopped the lockdowns of 2020 if he hadn’t tragically passed away shortly before they happened. As Henderson wrote:

The interest in quarantine reflects the views and conditions prevalent more than 50 years ago, when much less was known about the epidemiology of infectious diseases and when there was far less international and domestic travel in a less densely populated world… The negative consequences of largescale quarantine are so extreme(forced confinement of sick people with the well; complete restriction of movement of large populations; difficulty in getting critical supplies, medicines, and food to people inside the quarantine zone) that this mitigation measure should be eliminated from serious consideration.

However, throughout the 20th century, as the principle of herd immunity came to prominence and saved the western world from epidemic after epidemic, the west and China were often in a state of war, and relations between them were limited. Thus, just as the western Enlightenment largely passed China by when the institutions of feudalism were grandfathered into communism, the medieval concept of lockdown (封锁) was grandfathered into the policy of the CCP and remained central to the CCP’s public health policy. The public health epistemology of the west and China thus diverged, until some officials in the western public health and biosecurity establishment decided to re-import the concept of lockdown from China back into western pandemic policy with the new name of “social distancing.”

How “Lockdown” Was Re-Imported Into the Western World as “Social Distancing”

It remains unclear why exactly the decision to re-import the concept of lockdown back into the western world was made. The WHO first began discussing mass community-wide closures as public health policy during an international meeting on the response to SARS in October 2003, ostensibly based on what China had done. The greater epidemiology community started using “social distance” as an epidemiological term for mass closures shortly thereafter.

Then, in January 2004, this concept of mass closures suddenly appeared in great detail as official US CDC policy for the response to SARS, with the official name of “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance.” By mid-2004, the WHO had also picked up the use of the term “social distance” for community-wide closures, without really endorsing them. The 2004 CDC guidance on “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” contains no citations, so it’s unclear where exactly it came from; in response to inquiries, a CDC representative responded only with a link containing a lot of info on events in China.

Everything about this timeline utterly belies the story of the “birth of social distancing” as told by the New York Times and Michael Lewis. But important information on the importation of these lockdown measures can still be gleaned from their concocted story.

Somewhat inexplicably, in the late 1990s a subset of the western national security community developed a kind of fixation on bioterrorism and began conducting high-level simulations that often involved mass quarantines, such as Dark Winter in 2001. One member of this subset was an oncologist named Richard Hatchett, now Chief Executive of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), who is credited by the New York Times and Michael Lewis with inventing the concept of “social distancing.” According to the Times, it all began in 2005:

The effort began in the summer of 2005 when Mr. Bush, already concerned with bioterrorism after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, read a forthcoming book, ‘The Great Influenza,’ by John M. Barry, about the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918… To develop ideas, the Bush administration enlisted Dr. [Richard] Hatchett, who had served as a White House biodefense policy adviser, and Dr. [Carter] Mecher, who was a Veterans Affairs medical officer in Georgia overseeing care in the Southeast.

Already, the story begs credulity: We’re meant to believe that George W. Bush read a book. But worse, the record is abundantly clear that “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” were already official CDC policy well before 2005.

While they were thinking about ways to combat a pandemic, so the story went, Hatchett and Mecher were contacted by Robert Glass, whose 14-year-old daughter had done a school science project on preventing contagion by shutting down schools. Hatchett, Mecher, and other researchers then did studies portending to show that through community-wide closures, St. Louis had achieved better results than Philadelphia during the Spanish flu in 1918. Hatchett and Mecher then used these studies to push the concept of “social distancing” through the CDC and the federal bureaucracy until it was accepted as official policy in 2007.

The concept of social distancing is now intimately familiar to almost everyone. But as it first made its way through the federal bureaucracy in 2006 and 2007, it was viewed as impractical, unnecessary and politically infeasible… But within the Bush administration, they were encouraged to keep at it and follow the science. And ultimately, their arguments proved persuasive…

In February 2007, the CDC made their approach—bureaucratically called Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, or NPIs—official US policy.

But again, the record is abundantly clear that the CDC had already made Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance “official US policy” in January 2004.

Hatchett claims that he invented the use of the term “social distance” for epidemiological purposes. Previously, the term had been used for about a century as a negative sociological term for stigmatization based on race, class, or health status. Per Lewis:

As communicable disease spreads through social networks, Richard reasoned, you had to find ways to disrupt those networks. And the easiest way to do that was to move people physically farther apart from each other. ‘Increasing Effective Social Distance as a Strategy,’ he called it. ‘Social distance’ had been used by anthropologists to describe kinship, but he didn’t know that at the time, and so he thought he was giving birth to a phrase.

This story is, again, belied by the fact that the CDC had already enacted“Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” in January 2004. So either Hatchett did not actually invent the term “social distance” for epidemiological use, or he was in contact with the CDC several years before he says he was.

Lewis goes on with the story of Hatchett’s crusade at the CDC:

The story that Lisa planned to tell in her book would build to a tipping point, a meeting that ran for two days, December 11–12, 2006. It amounted to a final showdown on this new, but also ancient, strategy for disease control… By then several inside the CDC were on board, including the CDC’s head of global migration and quarantine, Marty Cetron… ‘We won!’ That was the moment the CDC accepted various forms of social distancing as a viable tool.

Yes, it’s not surprising that “several inside the CDC were on board” with social distancing in 2006, given the CDC had already enacted it as policy in January 2004.

That was also when Carter [Mecher] fully infiltrated the Centers for Disease Control. The morning after the hotel meeting, he dressed in what amounted to a CDC costume: Birkenstocks, a loose-fitting shirt, and khaki pants to match—or not. He drove to a CDC campus in Atlanta; there Lisa badged him in and led him to Marty Cetron’s office. Marty had left for a ski trip in Europe. Carter sat at a desk and, consulting with Richard over the phone, wrote the CDC’s new policy, which called for social distancing in the event of any pandemic… school closure and social distancing of kids and bans on mass gatherings and other interventions would be central to the future pandemic strategy of the United States—and not just the United States. ‘The CDC was the world’s leading health agency,’ said Lisa. ‘When the CDC publishes something, it is not just the CDC talking to the US but to the entire world’…

After [Mecher] left, people seemed to forget he’d ever been there. By February 2007, when the CDC published the new strategy, if you asked anyone inside the place who had written it, they’d have given you the name of a man inside the CDC. Marty Cetron, or maybe someone who worked for him…

Bossert had watched Carter and Richard reinvent pandemic planning, reinterpret the greatest pandemic in human history, resurrect the idea that a society could control a new disease by using social distancing in its various forms, and then somehow lead the CDC to the conclusion that the whole thing had been their idea.

There’s a lot wrong here. First of all, why did the CDC’s head of global migration and quarantine, Marty Cetron, let Carter Mecher sit at his desk in the CDC and write an entirely new pandemic policy—a policy that would affect not just the US, “but the entire world”? While he left for a ski trip in Europe? We’re going to “reinvent pandemic planning”—unraveling an entire century of epidemiological knowledge not just for the country, but for the whole world—you got this Carter, I’ll be out skiing in the Alps!

Then there’s the fact that no one at the CDC even remembered any of this—the CDC, which is our repository for epidemiological knowledge. According to Lewis, Hatchett and Mecher led “the CDC to the conclusion that the whole thing had been their idea.” Perhaps that wasn’t so difficult, given “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” had already been CDC policy in January 2004, indicating that it had, in fact, always been their idea.

In Lewis’s book, Richard Hatchett pays due reverence to D.A. Henderson.

Donald Ainslie Henderson was maybe six foot two, but in Richard’s mind he stood twelve foot six and loomed even larger in his field.

It’s unclear whether Hatchett actually believed any of this about Henderson, or whether his reverence was simply a means to ingratiate himself with Henderson and other public health officials, given that virtually everything Hatchett did amounted to an unraveling of Henderson’s life work. It’s also unclear why exactly Hatchett felt this burning need to roll back an entire century of western epidemiological knowledge.

Richard couldn’t understand his certainty, or the weird conventional wisdom that had coalesced. ‘One thing that’s inarguably true is that if you got everyone and locked each of them in their own room and didn’t let them talk to anyone, you would not have any disease,’ he said. ‘The question was can you do anything in the real world.’

The problem is, Richard’s assertion that “if you got everyone and locked each of them in their own room … you would not have any disease” is in reality inarguably false. In fact, during Covid, even groups of researchers who were completely isolated in Antarctica, all of whom took ample public health precautions and none of whom tested positive before the trip, experienced Covid outbreaks.

The truth is, even in our modern world, despite our formidable knowledge of so many subjects, our collective knowledge of viruses is nowhere near as sophisticated as is commonly believed. Perhaps in the 22nd century people will look back and laugh at our primitive understanding of virology. But for now, we simply don’t know why infections crop up even in long-isolated individuals. Herd immunity takes this knowledge deficit into account and has long been central to best public health practices based on what we do know.

But for whatever reason, owing to the CDC’s sudden passage of “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” in January 2004 and Hatchett’s subsequent efforts, the medieval concept of lockdown (封锁) had now been re-imported into western pandemic planning as “social distancing.”

These events soon triggered their very own reverse-Enlightenment, with teams of scientists, often physicists like Neil Ferguson, churning out model after model claiming to prove the effectiveness of mass quarantines and “social distancing,” spinning an illusion that the revival of this medieval policy represented some new scientific breakthrough. 99.9% of the population had no reason to know or think about any of this until 2020, when these measures were suddenly unleashed indiscriminately across the western world, often skipping the modern name of “social distancing” altogether and defaulting instead to the original Chinese name of “lockdown.”

Contemporary Usage of “Lockdown” vs “Social Distancing

The term “Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” in its first use by the CDC appears to have simply been lifted from China’s lockdown measures during SARS. Thus, “social distancing” is simply a western name for the ancient Chinese concept of lockdown (封锁). For this reason, it’s perhaps not surprising that officials often use the terms interchangeably. But important and sometimes galling information can be gleaned from how the use of these two terms has diverged since the inception of “social distance” as an epidemiological term in 2004, and especially since the mass Covid lockdowns of spring 2020.

For example, during the lockdowns in Sierra Leone in 2014, the millions of foreign bot posts promoting the concept of lockdown specifically used the Chinese term of “lockdown” rather than the western term of “social distancing,” indicating that whoever was behind this bot campaign to export lockdowns to Sierra Leone was inspired to do so by China’s lockdowns rather than the western interest in “social distancing.”

Likewise, the countless thousands of bots who promoted the concept of “lockdown” around the world in March 2020 also used the Chinese term of “lockdown” rather than the western term of “social distancing.”

Naturally, for this same reason, you won’t find Chinese state media using the western term of “social distancing” to describe these measures; they use the Chinese term of “lockdown.”

None of this information diminishes the fact that Xi Jinping’s massive lockdowns in response to Covid in January 2020 were, in the words of the WHO, “new to science” and “unprecedented in public health history.” Perhaps Xi’s most notable contribution to the field was his introduction of the concept of welding people into their homes; welding had no precedent in public health policy.

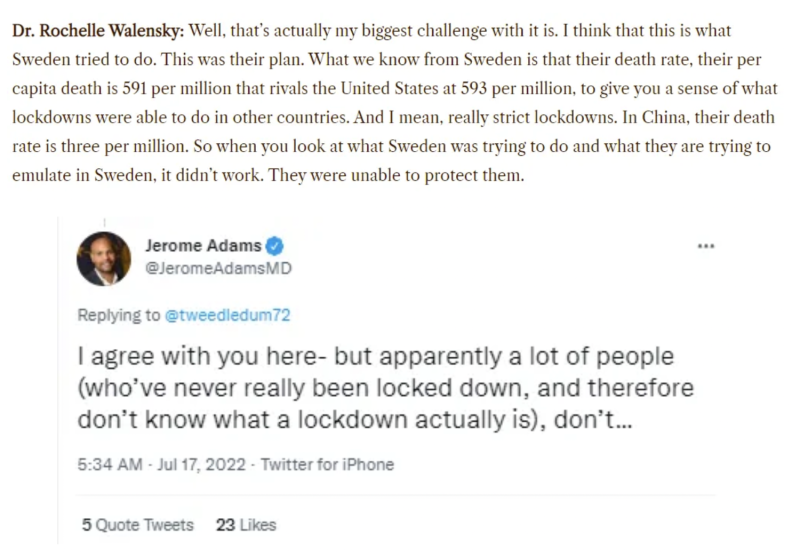

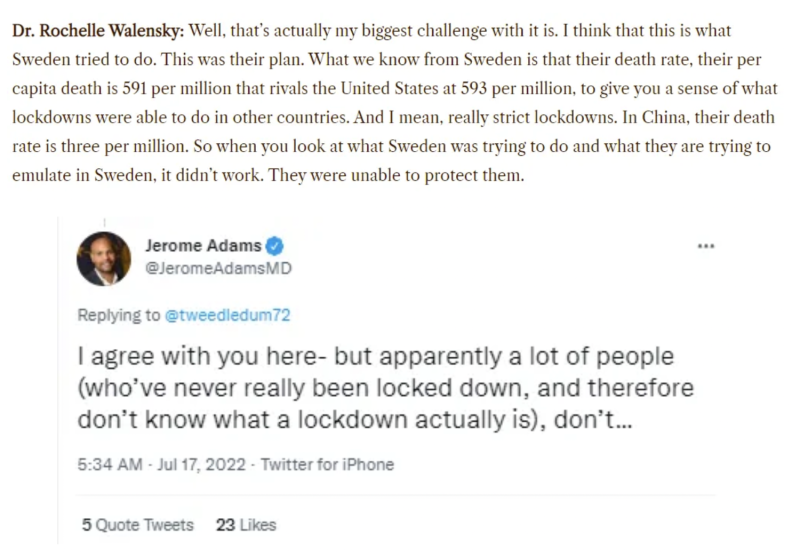

Throughout the response to Covid, countless leading journalists, influencers, and even political and public health officials have called for the imposition of a “real lockdown,” or blamed the failure of the western response to Covid on the failure to implement a “real lockdown.” However, since the record is quite clear that “social distancing” is simply the western name for the Chinese concept of “lockdown (封锁),” it’s unclear what exactly these commenters and officials meant by a “real lockdown.”

The truth is that anyone who experienced any kind of social distancing was experiencing a real “lockdown.” Further, “lockdown” was not mentioned in any western country’s pandemic plan. So when these leading officials, journalists, and influencers invoked the concept of a “real lockdown,” to what exactly were they referring? Presumably some were invoking Xi Jinping’s policy of a lockdown so strict as to weld people into their homes, or in some cases, by “real lockdown” they simply meant stricter and more forceful mandates in the abstract sense.

In other instances, leading officials in the response to Covid have used the terms “social distancing” and “lockdown” interchangeably. For example, in her strange book Silent Invasion, White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator Deborah Birx says that China employed “social distancing” during SARS in 2003:

One of the things that had kept the SARS case fatality rate from being worse was that, in Asia, the population (young and old alike) adopted the wearing of masks routinely, to protect themselves from air pollution and infections in crowded indoor and outdoor spaces when social distancing wasn’t possible.

This is technically incorrect. “Social distancing” had not yet been invented as an epidemiological term in 2003; rather, the Chinese had employed“lockdown” (封锁). But to-may-to/to-mah-to I suppose.

Perhaps this is why Birx, the leading official in charge of the US response to Covid, then shows no qualms about having wanted to impose “lockdown”—using the Chinese term—on the American people.

At this point, I wasn’t about to use the words lockdown or shutdown. If I had uttered either of those in early March, after being at the White House only one week, the political, nonmedical members of the task force would have dismissed me as too alarmist, too doom-and-gloom, too reliant on feelings and not facts…

On Monday and Tuesday, while sorting through the CDC data issues, we worked simultaneously to develop the flatten-the-curve guidance I hoped to present to the vice president at week’s end. Getting buy-in on the simple mitigation measures every American could take was just the first step leading to longer and more aggressive interventions. We had to make these palatable to the administration by avoiding the obvious appearance of a full Italian lockdown.

Italian Health Minister Roberto Speranza, the man who signed several of the first pandemic lockdown orders in the modern western world, likewise uses the Chinese term “lockdown” in his book:

It is the moment of general closure, of the lockdown for a large area of Northern Italy. It is a very hard measure, never before applied in the West.

Indeed, the concept of a mandatory “lockdown” had no precedent in the western world; rather, western pandemic plans recommended only voluntary “social distancing” measures. But given “social distancing” had originated as the western name for “lockdown (封锁),” perhaps the closures contemplated in these pandemic plans were never really meant to be “voluntary” after all—whatever a “voluntary” closure even is. In Birx’s words:

[T]he recommendations served as the basis for governors to mandate the flattening-the-curve shutdowns… With the White House’s “this is serious” message, governors now had “permission” to mount a proportionate response and, one by one, other states followed suit. California was first, doing so on March 18. New York followed on March 20. Illinois, which had declared its own state of emergency on March 9, issued shelter-in-place orders on March 21. Louisiana did so on the twenty-second. In relatively short order by the end of March and the first week of April, there were few holdouts. The circuit-breaking, flattening-the-curve shutdown had begun.

Conclusion

“Community-Wide Measures to Increase Social Distance” had already been promulgated by the CDC into federal policy by January 2004, having apparently been lifted directly from China’s lockdown (封锁) measures during SARS. This concept of “lockdown,” or mass closures, had many precedents in ancient and medieval times but was overwhelmingly discredited by western epidemiological research in the 20th century. Western responses to 20th century epidemics thus centered around the principle of “herd immunity” with so much success that most people hardly noticed them.

“Social distancing” is therefore simply the western term for “lockdown.” The official story of the birth of social distancing based on a 14-year-old’s 2006 science project as told by the New York Times and Michael Lewis thus falls apart entirely and appears to be an elaborate cover story for the Chinese origin of the concept.

For this reason, the interchangeable use by many key officials during the response to Covid of the terms “lockdown” and “social distancing” is notable, as are the large-scale propaganda campaigns which specifically used the term “lockdown.” Broad appeals among western officials and media outlets for the implementation of a “real lockdown” are especially odd, given that “social distancing” was born as a synonym for “lockdown”; presumably some of these appeals were for measures more similar to Xi Jinping’s unprecedented lockdowns in early 2020 which involved welding doors and other totalitarian measures.

These facts raise several more questions. Who exactly was behind the importation of China’s lockdown measures into western policy in 2004, and why? What explains the national security community’s sudden fixation on bioterrorism and quarantine in the late 1990s? Was this fixation with quarantine simply a result of having too much military brass with an inadequate understanding of 20th century epidemiology, or something else? Who exactly gave George W. Bush that book about the Spanish flu in 2005? And why exactly have the officials and media outlets involved gone to such lengths to concoct cover stories and avoid association with the Chinese origin of these concepts?

One way or another, the ancient policy of “lockdown” in response to an outbreak thus came full circle. Having been thoroughly discredited as counterproductive by 20th-century epidemiological research, this medieval policy of lockdown (封锁) was kept alive in China due to the CCP’s limited contact with the west, only to be reintroduced into the west in the early 21st century, first through a gradual and mysterious process of influence, and then all at once in 2020 through a propaganda campaign of unprecedented scale.

Reprinted from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.