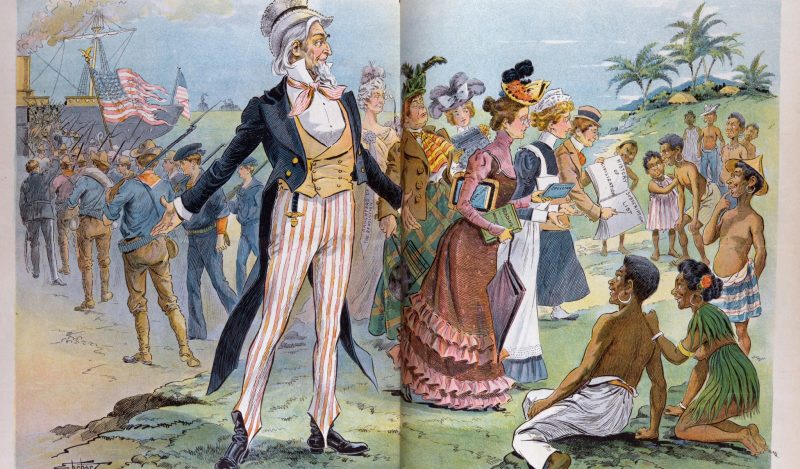

Social and political elites have long relied on euphemism to make their schemes of social control more palatable to those they see as their inferiors. Think here of “social distancing” or “mitigation measures” when they really mean forced separation and isolation.

Though such leaders pretend in certain moments to be comfortable with the use of brute force to achieve their desired domination of the masses, they are in reality quite frightened of going down that path, as they know that in an open conflict with the common people much can go wrong, and outcomes are anything but certain.

This is why they spend so much time and money on what Itamar Even-Zohar calls “culture-planning,” that is, arranging our semiotic environment in ways that naturalize schemas of social control that favor their interests, inducing in this way, what he calls “proneness” among considerable swathes of the population.

Why engage in conflict with the general population, with all that such conflicts portend in the way of unforeseen consequences when you can teach people to welcome externally generated schemas of domination into their lives as gifts of benevolence and social improvement?

The Making of Culture

Though it is often forgotten, culture is derived from the very same Latin root, colere, that gave us the verb to cultivate. To cultivate is, of course, to engage in a conscious process of husbandry within nature which, in turn, involves making repeated judgements about what one does and does not want growing, or even present, on a given patch of land.

Carrots and onions yes, weeds no.

Indeed, the very lack of specificity of the term weed tells us much about this process. Definitionally speaking, a weed has no inherent properties of its own. Rather, it is defined in purely terms of what it is not, that is, as something that the cultivator has deemed as having no positive use. In other words, there is no such thing as a garden without value judgments regarding the relative utility of various species of plants.

The field of what we call culture (with a capital C) not surprisingly, obeys similar imperatives. Like species of plants, the stocks of information around us are nearly infinite. What turns them into culture is the imposition upon them of a man-made order that supposes the existence of coherent relations between and among them through structure-engendering devices like syntax, narrative or concepts of esthetic harmony.

And as in the case of our garden, human judgment and the power to enforce it—a mechanism sometimes referred to as canon-making—are fundamental to the process. Just as in farming, there is no such thing as culture without human discernment and the exercise of power.

So, if we seek to truly understand the cultural sea in which we swim and its effects on the way we view “reality” we need to keep a close eye on the prime canon-making institutions in our cultural field (government, universities, Hollywood, Big Media, and Big Advertising) and constantly ask hard questions about how the vested interests of those that run them might affect the conformation of the cultural “realities” they place before us.

Conversely, those in power, and desirous of staying there, know that they must do everything in their control to present these cultural “realities” not as what they are—the result of quite conscious canon-making processes run by institutionally empowered elites—, but as largely spontaneous derivations of the popular will, or even better, as mere “common sense.”

New Technologies and Epochal Change

These efforts to convince the people that “this is just the way things are” can often be quite successful, and for surprisingly long stretches of time. Think, for example, of how the Church of Rome used its stranglehold on the production of texts and large scale visual imagery to impose a largely uniform understanding of human teleology upon western European culture for the thousand years leading to the publication Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses in 1517.

As I have suggested in other places, the spread and subsequent consolidation of Luther’s challenge to Rome would have been impossible without the invention of the technology of moveable type by Gutenberg approximately a half-century earlier. Others before the monk of Wittenberg had sought to challenge Rome’s monopoly on the truth. But their efforts foundered on an inability to spread their challenges to potential new adepts easily and quickly. The printing press changed all that.

Like Gutenberg’s invention, the advent of the internet nearly three decades ago radically enhanced most common people’s access to information, and from there, their comprehension of the important, and often nefarious role of canon-makers, or what we more commonly refer to as gatekeepers, in configuring operatives schemas of “reality” in their lives.

It is not clear whether those that decided to place this powerful tool at the disposal of the public in the mid-90s anticipated the challenges it might pose to the ability to generate narratives amenable to the long-term interests of our entrenched centers of financial, military and social power. My guess is that they did, but that they assumed, perhaps correctly, that the ability to gather information about their own citizens through these same technologies would more than compensate for that potential danger.

And they had, I think, what they realized was one other very important card up their sleeve in their ongoing efforts to enhance their control of the public. It was their ability—as one participant in the Event 201 Covid simulation event from 2019 candidly put it—to “flood the zone” with information when they viewed it as necessary, generating in this way, an acute hunger in the population for top-down expert guidance.

Social Control Through Informational Scarcity….and also Informational Abundance

Up until the advent of the internet, elite-generated systems of narrative control pivoted, for the most part, on their ability to deprive citizens of information that might allow them to generate visions of reality that challenged “common sense” understandings of how “the world really works”. And in the end, in fact, this remains their goal.

What is different today are mechanisms they have developed to achieve this end.

No one, especially no one raised in a consumer culture where the individual’s “right to choose” has been raised to a paramount social value, likes to be told they cannot freely access this or that thing.

So how then can the elite culture-planner achieve the results of information control without setting off the alarms that frontal censorship would set off among the parishioners of the contemporary church of choice?

The answer—to go back to our metaphorical garden—is to seed the patch of land with weeds while its owner is away and return a short time later as a salesman bearing a new and completely effective cure against the plague that threatens his agricultural holdings.

Put another way, today’s culture-planners are keenly aware of two things. One, that the initial liberatory jolt provided by the amount of information suddenly available through the internet has, for all but the most skilled and disciplined parsers of information, long-since faded, and has been replaced by information overload, with the inchoate sense of confusion and dread that his condition carries with it. Two, that human beings are, as the history of agriculture and the multitude of other pursuits derived from its original organizational impulse demonstrate, order-craving creatures.

In this context, they know that if they want to exercise control over the information diet of the many without recurring to frontal censorship they simply need heighten the volume and contradictory content of the information at the disposal of the many, wait for them to tire and become exasperated trying to figure it all out, and then present themselves as the solution to their growing sense disorientation and exhaustion.

And sadly, many, if not most people will see their submission to the supposed mental clarity offered them by authorities not as the abject capitulation of their individuality decision-king prerogative it is, but as a form of liberation. And they will attach to the authority figure’s person and/or the institution he or she represents, a devotion quite similar to that which a child will offer a person they perceive as having saved them from a perilous situation.

This is the infantilizing dynamic at the center of the fact-checking industry. And as is the case in all relationships between clerics and commoners, its vigor and durability is greatly enhanced by the deployment, on the part of the clerics, of an ideal that is both highly attractive and flatly impossible to achieve.

The unicorn of unbiased news

If there is one element that is found in virtually all of the fascist movements of the 20th century it is their leaders’ rhetorical pose of being above the frequently off-putting hurly-burly of politics. But, of course, no one operating in the public arena is ever above politics, or for that matter, ideology, both of which are just two more examples of the structure-engendering cultural practices alluded to above.

The same thing is true, as we have seen, in the matter of discourse which is our prime tool for turning raw information into cultural artifacts that suggest palpable meanings. As Hayden White makes clear in his masterful Metahistory, there is no such thing as a “virgin” approach to turning an agglomeration of facts into a coherent rendering of the past. Why? Because every writer or speaker of history is also necessarily a previous reader of it, and as such, has internalized a series of verbal conventions that are deeply freighted with ideological meanings.

He reminds us, moreover, that every act of narration undertaken by a writer involves both the suppression and/or foregrounding of certain facts in relation to others. So even if you provide two writers with the exact same factual materials, they will inevitably produce narratives that are different in their tone, as well as their implied semantic and ideological postures.

We can thus say that while there are more or less careful chroniclers of the social reality (the first groups type being conscious of the above-sketched complexities and traps, while the second group are far less so) what there are not, and never will be, are fully objective or unbiased ones

Confounding the matter further is the infinitely complex set of suppositions, often rooted in collective history and personal context, that a given reader brings to the task of deciphering the already freighted choices of the chronicler, something that Terry Eagleton points out in humorous fashion in the following passage.

Consider a prosaic, quite unambiguous statement like the one sometimes seen in the London Underground system: ‘Dogs must be carried on the escalator.’ This is not perhaps quite as unambiguous as it seems at first sight: does it mean that you must carry a dog on the escalator? Are you likely to be banned from the escalator unless you can find some stray mongrel to clutch in your arms on the way up? Many apparently straightforward notices contain such ambiguities: ‘Refuse to be put in this basket,’ for instance, or the British road-sign ‘Way Out’ as read by a Californian.

When we take the time to think about it, we can see that human communication is extremely complicated, necessarily ambiguous, and full of misunderstandings. It is, as is often said about baseball, “a game of percentages” in which what we say, or our interlocutor heard, will often differ greatly from the concept or idea that might have seemed crystal clear in our minds before we opened our mouths and tried to share it with that person.

This inherently “relational,” and therefore slippery nature of language, and hence the impossibility of expressing absolute, immutable or wholly objective truths through any of its modalities has been widely understood since the promulgations of Saussure’s linguistic theories in the early years of the 20th century, and needless to say, in a less abstract manner for thousands of years before that.

But now our “fact-checkers” are telling us that this is not the case, that there is such a thing as fully objective news that exists above the din of necessarily partial and gaffe-laden human dialogues, and surprise, surprise, they just happen to possess it.

This is, in the very real genealogical sense, a fascist trick if there ever was one.

As much as they liked to suggest it, Mussolini, Franco, Salazar and Hitler were never above politics or ideology. And our fact checkers are not, and never will be above linguistic and therefore, conceptual imprecision and semantic shading.

Why? Because no one or no institution ever is above politics. And anyone who tells or suggests that they are or can be is—no need beating around the bush—an authoritarian who either does not understand the workings of human freedom democracy, or does, and is quite intentionally trying to destroy it.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.