Harris Coulter has written an academic and fascinating four-volume set of books on the history of Western Medicine, brought back into print by Brownstone Institute:

Volume I: The Patterns Emerge: Hippocrates to Paracelsus

Volume II: Progress and Regress: J.B. Van Helmont to Claude Bernard

Volume III: Science and Ethics in American Medicine: 1800-1914

Volume IV, Part One: Twentieth-Century Medicine: The Bacteriological Era

Volume IV, Part Two: Twentieth-Century Medicine: The Bacteriological Era

Each volume is important to those who wish to understand the roots of modern medicine and to learn how and why many “unorthodox” practices did not gain general acceptance in the health care system. The four books are of particular importance to those involved in holistic approaches to health because Coulter traces the history of the holistic (AKA “empirical”) practices that are often ignored or criticized unfairly in most medical history texts.

Ultimately, books on history are written by the “victors;” that is, by the dominant political or medical paradigm, and such books give an inadequately accurate view of true history. The books written by Dr. Coulter are therefore a refreshing and even compelling review of medical history. Coulter’s books show that what we call “scientific medicine” today isn’t really scientific but “reductionistic;” that is, these conventional medical treatments tend to provide short-term a highly limited assessment of health benefits from treatment, often ignoring the fact that such treatments provided only short-term benefits while creating many side effects that later led to chronic and deeper diseases.

The four volumes are scholarly written and are thoroughly footnoted with references to thousands of original writings. Volume I describes the era from Hippocrates (400 B.C.) to Paracelsus (1600). Volume II discusses medicine in Europe from 1600 to 1850. Volume III covers medicine in America from 1800 to 1914. Volume IV covers Twentieth-century Medicine: The Bacteriological Era (this volume is itself separated into two volumes, Part I and Part II).

The title, Divided Legacy, refers to the two predominant schools of thought or traditions that have dominated Western medical history (college courses in “philosophy” typically describe these two dominant schools of thought, and Coulter’s books describe how these two different philosophies manifest in medical thought and practice). Although the two schools were not formalized with every practitioner aligning him/herself with one or the other school, Coulter’s analysis shows convincing evidence how some of the best physicians and healers believed and practiced mainly in one or the other tradition.

One school was known as the Rationalist school, while the other was the Empirical school. The Rationalist school sought to understand health, disease, and the treatment of disease in an analytical fashion; It sought causes of disease and methods of treatment in a systematic and rational manner. It focused on the anatomical and biochemical nature of the human being as ways to understand the parts of the organism and how to make them function properly.

The Empirical school of thought held different assumptions about the ways of acquiring knowledge on health, disease, and the treatment of disease. It did not look for nor seek to understand the causes of disease. It sought and developed ways that worked whether or not the practitioner understood at first why the methods worked. Although Empirical practitioners usually had theories on how and why their methods worked, they recognized that their theories were always secondary to the fact that the method worked. Over long periods of time and through close observations, empirical practitioners developed their own time-tested and systematic health practices that were not based on an analytical understanding of cause and effect.

The Rationalist school, of which modern medicine is the latest development, has claimed the title of being the “scientific” medicine. At the same time, it asserted that other approaches to understanding health and to the treatment of disease were unscientific and were often to be considered as “quackery.” The meaning and significance of scientific methodology are discussed in detail in volumes II, III, and IV of Divided Legacy.

Coulter points out that although the Rationalists explained why their methods worked or didn’t work, their explanations were soon disproven and were replaced by a new set of “facts.” Comparatively, Coulter describes the scientific characteristics of the Empirical school and how and why their observations and their health practices have been utilized for long periods of time. Whether the outcomes have been successful has not been adequately determined statistically; however, the great numbers of people over many centuries who have made use of the various Empirical health practices should encourage clinicians and researchers to look more closely at Empirical perspectives and practices.

It should be clarified that the definition and the historical use of the word “empirical” refers to the dependence upon observation and experience alone without the use of theory or reductionistic methodology. Although modern medicine is considered a highly empirical science, it is much more rationally based than empirically based. Modern medicine’s emphasis on reductionistic methodology is different from traditional empirical practices that gauged improvement in health in holistic terms. Despite this, Coulter does not infer that the Rationalist’s practices don’t have some empirical basis or that Empirical practices don’t have some rational basis. Coulter’s books help us understand the distinct primary emphases of the two schools of medical thought.

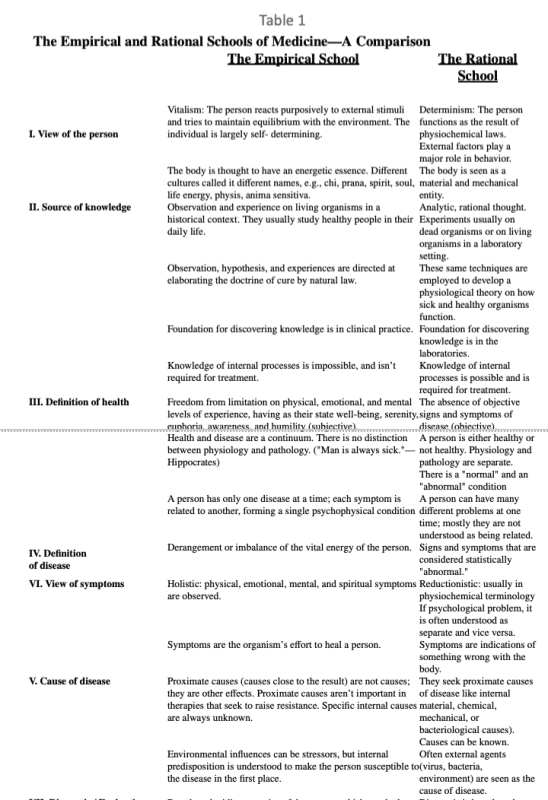

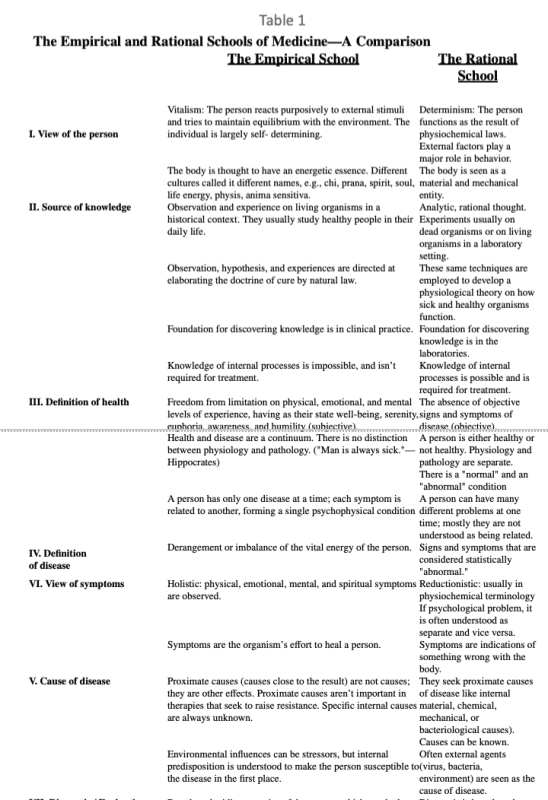

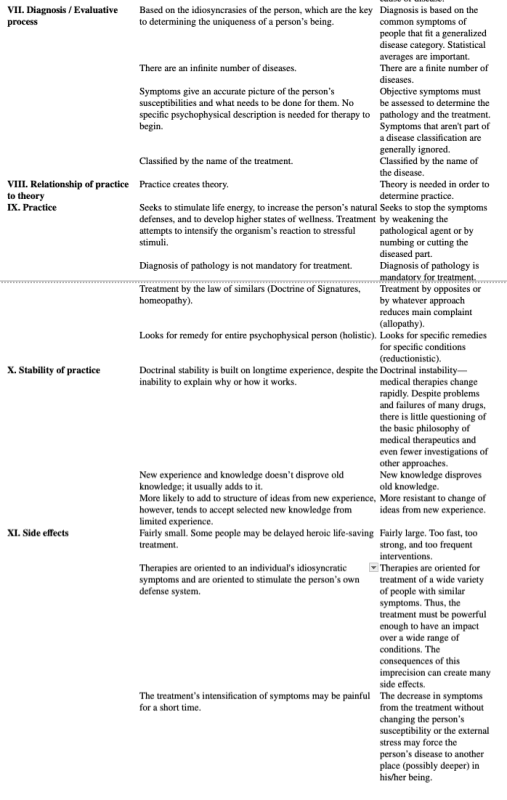

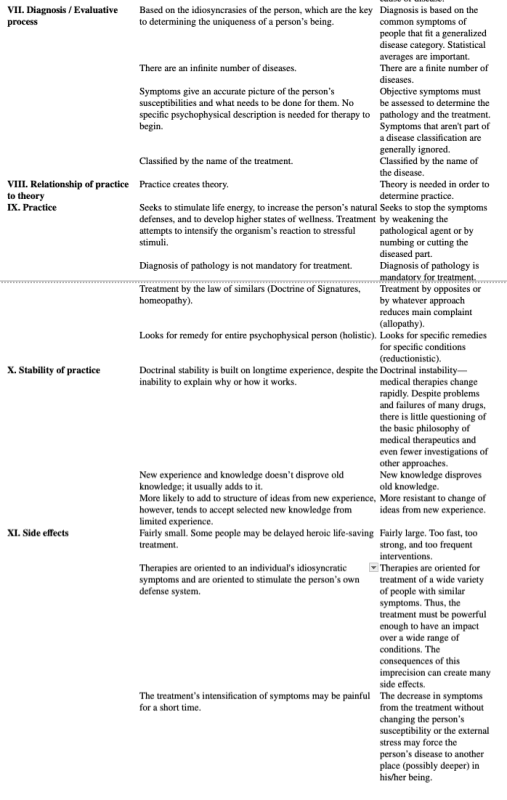

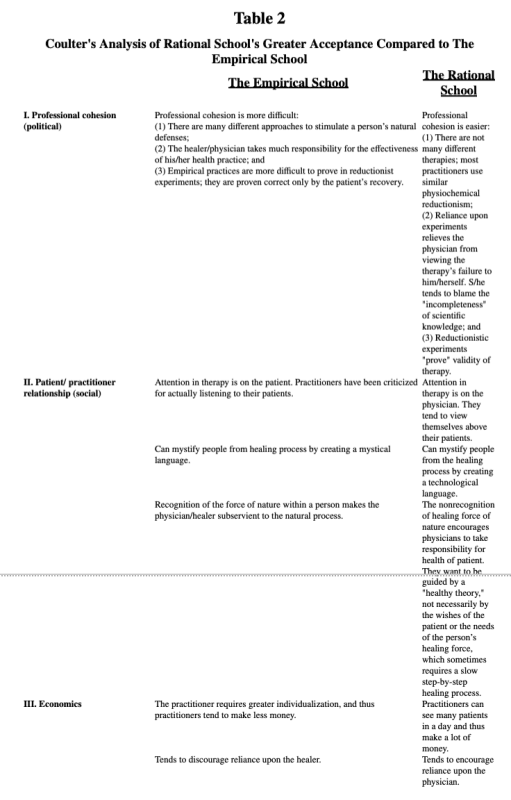

See Table 1 for an outline of the basic assumptions of the Rationalist and Empirical schools of medicine.

Whether the Rationalist or the Empirical school of medicine appears to be more appropriate does not depend upon which approach seems more scientific. It ultimately depends upon which set of assumptions, summarized above, the practitioner has about human beings, about the definition of health, about obtaining knowledge, and about understanding the universe.

Coulter’s preference or bias for the Empirical school is made known throughout the book. Coulter includes in each chapter statements of some of the great physicians/healers/theorists in history. Thomas Sydenham, a celebrated English physician in the 17th century who is considered the English Hippocrates, referred to the work of the Rationalists as “the art of talking rather than the art of healing.” (Vol. II, p. 681)

Dr. Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843), the German physician and father of homeopathic medicine,* criticized the Rationalist school stating, “the vain fallacy that the business of the medical profession is to explain everything.” (Vol. II, p. 327) Rather, “they have never yet how to cure our fellow men in a manner that shall satisfy our conscience, but only how we may present to the people an appearance of learned wisdom and deep penetration” (Vol. II, p. 329). More trenchantly, Hahnemann asserts,

“They [the Rationalists] placed the essence of the medical art, and their own chief pride, in explaining even much of the inexplicable. They imagined it impossible to treat scientifically the abnormal states of the human body (diseases) without possessing a tangible idea of the fundamental laws of the normal and abnormal conditions of the human frame. Our system-builders delighted in these metaphysical heights where it was so easy to win territory; for in the boundless reaches of speculation everyone becomes a ruler who can effectually elevate himself beyond the domain of the senses. The superhuman aspect they derived from the erection of these stupendous castles in the air concealed their poverty in the art of healing.” (Vol. II, p. 328)

Hahnemann’s argument clearly had a strong basis during his life in the early 1800s when the majority of physicians practiced what most people today believe was dangerous medicine.

Through Coulter’s exhaustive research he also quotes from well-known Rationalists to support his thesis. Coulter quotes Claude Bernard, father of experimental physiology, who in turn quotes Baron Cuvier as saying, “All parts of a living body are interrelated; they can act only insofar as they act all together; trying to separate one from the whole means transferring it to the realm of dead substances; it means entirely changing its essence.” Bernard replies to this by stating, “If the above objections [to mechanistic physiology, a part of Rationalist thought well founded], we should either have to recognize that determinism is impossible in the phenomena of life, and this would be simply denying biological science; or else we should have to acknowledge that vital force must be studied by special methods and that science of life must rest on different principles from the science of inorganic bodies.” (Vol. II, p. 669)

Coulter’s point is that we do need special methods to study the vital energy of the human organism, and in fact, many of these methods have been in the developmental stages for over two centuries. These are the characteristics of the Empirical tradition.

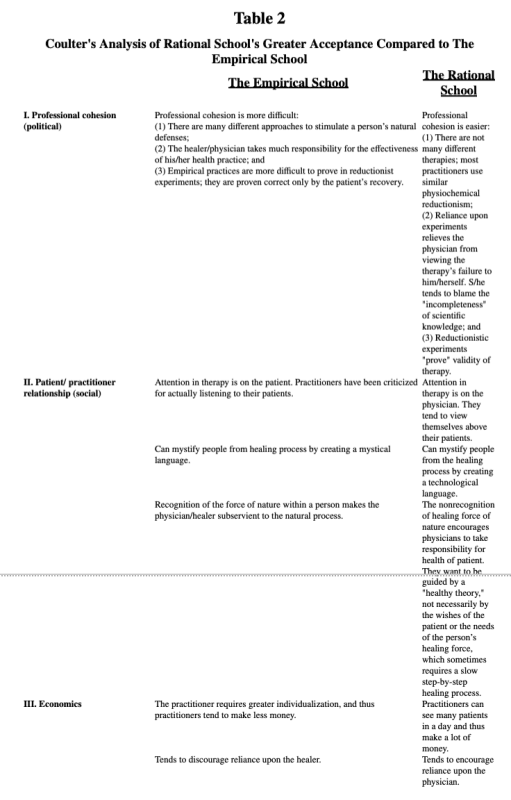

If the Empirical tradition embodies the characteristics of a scientific methodology to understand and heal the human being more fully, why hasn’t it gained greater acceptance? The three main reasons that Coulter describes for why the Rationalist rather than the Empirical school gained general acceptance were:

(1) political: the differences in the professional cohesion amongst the members within each school;

(2) social: the differences in the practitioner/patient relationship; and

(3) economic: the differences in the economics of being a practitioner in the different schools.

See Table 2 for a comparison of these reasons.

One characteristic of the interaction between the two traditions that cannot be discerned in the above type of comparison is Coulter’s observation that the Empiricists were the agents of creative discovery, while the Rationalists tended to trim and adjust knowledge to the institutional and socioeconomic needs of their profession. Coulter cites this recurrent pattern throughout history in fascinating detail. Through the elaborate theories that the Rationalists erect, it seems that they are on the right track. Coulter, however, gives a greater perspective on medical history and shows that too often the Rationalists have been traveling down a narrow track.

It is essential to add that Coulter’s deep appreciation of Empirical practices as a scientific discipline with history-tested results does not preclude the appropriate use of our present highly developed Rational medicine. However, whether one’s background is the Rational or Empirical tradition, Coulter makes a strong case for much greater investigation and utilization of Empirical perspectives and practices than is occurring at the present time.

Although one may say that “holistic health,” “alternative medicine,” “natural medicine,” and “integrative health care” are simply some of the more recent names for the Empirical tradition, it is important to recognize that some unorthodox practices and practitioners follow the general assumptions of the Empirical tradition, while others definitely do not. In any case, anyone who is interested in the emerging field of integrative health care would learn much about the roots of this approach to health by reading any or all of Harris Coulter’s Divided Legacy. These books should be read by those involved in the integrative health movement and by those who want to know why our current medical care system is not responsive to the needs of our society.

Although homeopathy’s greatest popularity in the US was in the late 1800s and early 1900s when between 20% to 25% of urban physicians considered themselves homeopaths, homeopathy itself sharply declined after this time, though a significant resurgence began in the late 20th century and continues today.

NOTE (Regarding Table 1 and Table 2): This comparison describes the general view of the two schools of thought. Not every practitioner consistently believed or practiced each assumption. Some of the descriptions represent the extremist and the more classic assumptions of the two schools. Coulter documents how most of these assumptions pervade the thinking and practice of the majority of health practitioners

* Coulter considers homeopathy to be the most sophisticated manifestation of the Empirical tradition in medicine. He claims that homeopathy’s use of toxicology experiments (called “provings”) help determine what a medicinal substance CAUSES in overdose and therefore what it will be effective in healing in specially prepared microdoses. Ultimately, Coulter shows that homeopathic medicine is based on a strong scientific basis, even though its practitioners had not yet concretely explained how these special extremely small doses elicited their healing response.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.