Evidence continues to mount indicating that the global response to the Covid-19 pandemic was counterproductive and harmful, yet mainstream opinion continues to proclaim that it was a triumph.

This is based on scientific papers that often manipulate the data or present it selectively.

Exhibit 1: Cohort study of cardiovascular safety of different Covid-19 vaccination doses among 46 million adults in England by Ip et al. The authors conclude that ‘the incidence of common arterial thrombotic events (mainly acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke) was generally lower after each vaccine dose, brand and combination’ and ‘the incidence of common venous thrombotic events (mainly pulmonary embolism and lower limb deep venous thrombosis) was lower after vaccination.’

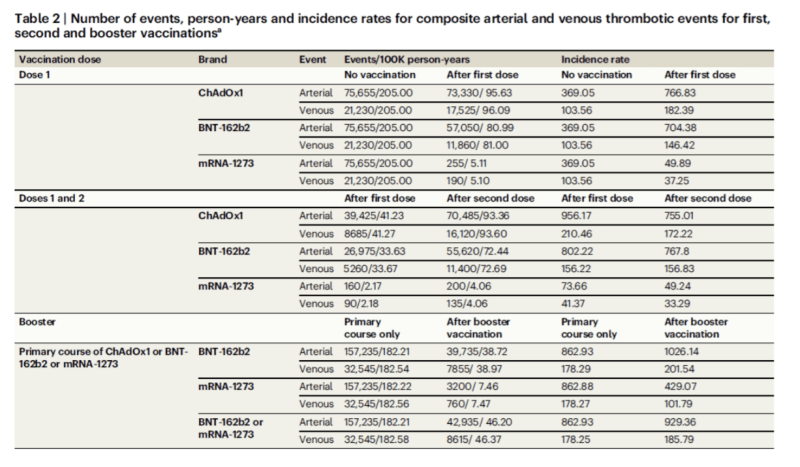

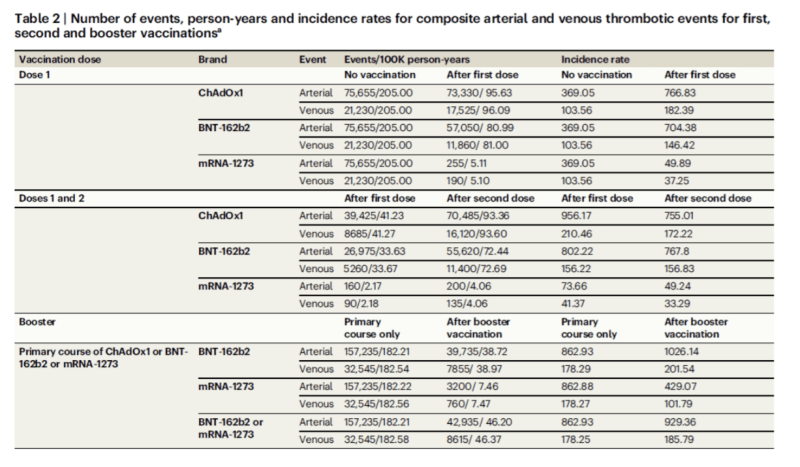

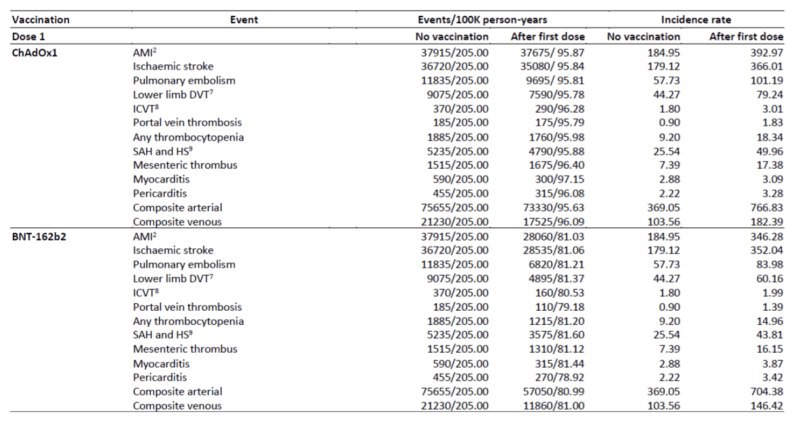

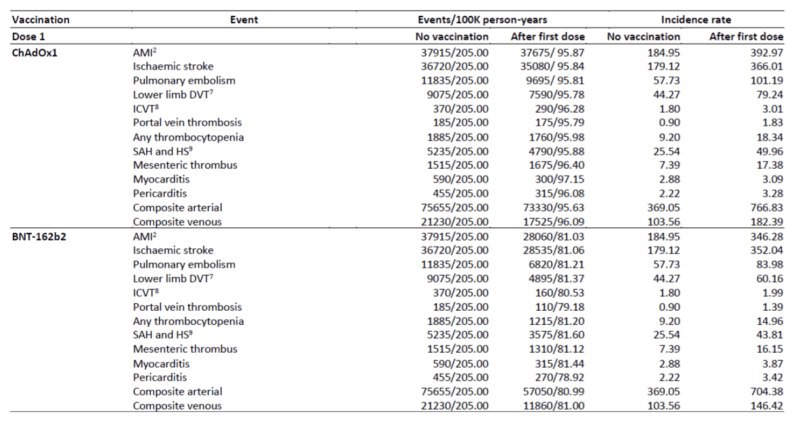

This seems to be a straightforward outcome, based on a most inclusive sample – the whole population of England. However, Table 2 shows incidence rates of cardiovascular events were substantially higher (nearly double for arterial events) after the first dose of the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines, compared to no vaccination:

This contradicts the text: ‘The incidence of thrombotic and cardiovascular complications was generally lower after each dose of each vaccine brand.’ Of course, ‘generally’ is a weasel word. It means that the incidence of complications after each dose was lower except where it was higher. Incidence rates for the Moderna vaccine were indeed much lower at least in the medium term (up to 26 weeks) but rates for AstraZeneca and Pfizer were much higher.

Incidence rates after the second dose were indeed ‘generally’ lower in the tables. But Supplementary Table 3 reveals that the definition of ‘no vaccination’ for Dose 2 in fact means the interval between a first dose and a second dose. The largest increases in incidence rates are for the Pfizer and AstraZeneca Dose 1 vaccination groups, the only cohorts compared with a true vaccination naïve control group.

Returning to Table 2, the vaccinated group and the unvaccinated groups have comparable numbers of events, but the vaccinated groups are calculated with reference to approximately half the number of person years. If we apply the incidence rates to the numbers of people in each group (at the top of Table 1), we can calculate vaccination with the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines brought about in the region of 91,000 additional serious cardiac events (euphemistically described as ‘complications’) compared to the no vaccination group in a little over one year. On the other hand, the Moderna group experienced over 34,000 fewer events compared with the no vaccination group, leading to an overall balance of around 56,000 additional events. How many of the individuals who had additional heart attacks, strokes, and thromboses subsequently died? The results are shocking, but after further processing we are told they are ‘reassuring.’

To obscure the alarming results, the text relies not on the straight incidence rates but on hazard ratios ‘adjusting for a wide range of potential confounding factors.’

It is not apparent why any adjustment was necessary. On the one hand, ‘There were few differences between subgroups defined by demographic and clinical characteristics,’ and on the other hand, ‘we addressed potential confounding by adjusting for a wide range of demographic factors and prior diagnoses.’ Were there significant differences in demographics or weren’t there?

Further on, we are told that ‘Subgroup analyses by age group, ethnic group, previous history of the event of interest and sex were conducted’ and outcomes ‘were generally similar across subgroups.’ What were the potentially confounding factors that had to be adjusted for if not these? How could an incidence rate of approximately 1.9 for the Pfizer Dose 1 arterial events be adjusted to a hazard ratio of 0.9?

If an adjustment leads to the reversal of findings of this magnitude, then it must be done transparently and with full substantiation. Without further explanation, the adjustment seems extraordinary and unjustifiable if outcomes were similar across subgroups and no differentiating factor is identified. They are statistical artefacts of low credibility and should not be used to guide policy.

This is a well-established academic trope – something that seems on the face of it to be black is not really black, but when ‘adjusted’ in an undisclosed and untransparent way has many white characteristics.

Table 2 compares the ‘primary course’ rates with the ‘after booster vaccination’ rates, where the Pfizer incidence rates are again higher for this last dose in the series, compounding the primary dose increase. I would have thought the authors should have commented on this, given that it contradicts the conclusions of the paper. This rise in the rate for vaccinated individuals with subsequent vaccinations is unlikely to be and is not in fact explained by confounding factors. We are told that both second dose-vaccinated and booster-vaccinated cohorts were older than the first dose cohort, so age does not seem to explain the rise. Other confounding factors are not revealed. Did they exist for any of the cohorts?

The authors also resort to breaking the data down into slices (dose by dose) in a way which prioritises the micro over the macro perspective, and obscures strategic synthesis.

After three doses (including boosters), how did the incidence rates of the vaccinated groups compare with that of the unvaccinated groups in toto, over the whole study period? Were they higher or lower overall? This is not revealed. What about after a year? Two years? Three years? Why are the Moderna rates so much lower, and why do they not discuss this? On the basis of the figures in the table, repeated doses of the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines pose unacceptable risks. Yet these were the main vaccines deployed in England in this period, approximately 90% of the total.

But on the basis of these misleading and selected statistics, unasked and unanswered questions, the authors triumphantly conclude:

These findings, in conjunction with the long-term higher risk of severe cardiovascular and other complications associated with COVID-19, offer compelling evidence supporting the net cardiovascular benefit of COVID vaccination.

This is a whitewash. Their unadjusted data show the reverse – most Covid-19 vaccinations increased cardiac risks. The fact that the authors studiously refrain from referring to or discussing the markedly adverse incidence ratios after vaccination is strongly indicative of bias, although at least they included them in the tables, taking a risk that close readers might notice their significance.

Many other studies perpetuate the whitewash, based on a zero-sum assumption that there are two mutually exclusive groups: unvaccinated people who fall victim to Covid-19 and vaccinated people who don’t.But the Cleveland Clinic preprint by Shrestha et al found that:

Consistent with similar findings in many prior studies…a higher number of prior vaccine doses was associated with a higher risk of COVID-19. The exact reason for this finding is not clear. It is possible that this may be related to the fact that vaccine-induced immunity is weaker and less durable than natural immunity….Thus, the short-term protection provided by a COVID-19 vaccine comes with a risk of increased susceptibility to COVID-19 in the future.

They reached the same conclusion in their peer-reviewed report on the effectiveness of the 2019 bivalent vaccines: ‘The risk of Covid-19 also increased with time since the most recent prior Covid-19 episode and with the number of vaccine doses previously received.’

Studies which show that vaccinated groups have much lower rates of infection than unvaccinated groups are usually founded on the ‘case-counting window bias,’ as explained in the peer-reviewed report on the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna by Alessandria et al. The vaccinated have lower numbers of infections in a defined window of time, but not necessarily beyond it. By contrast, the Cleveland Clinic studies above use a longer and additive timeframe, and Ip et al do not seem to exclude the first 14 days, which is a strength of their base statistics.

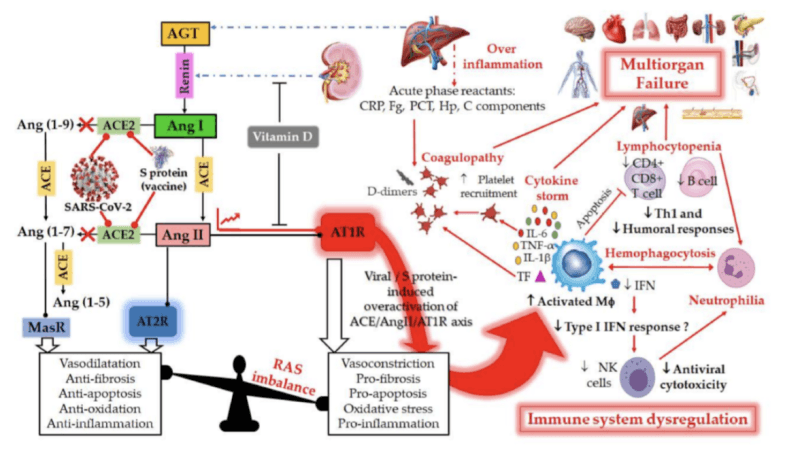

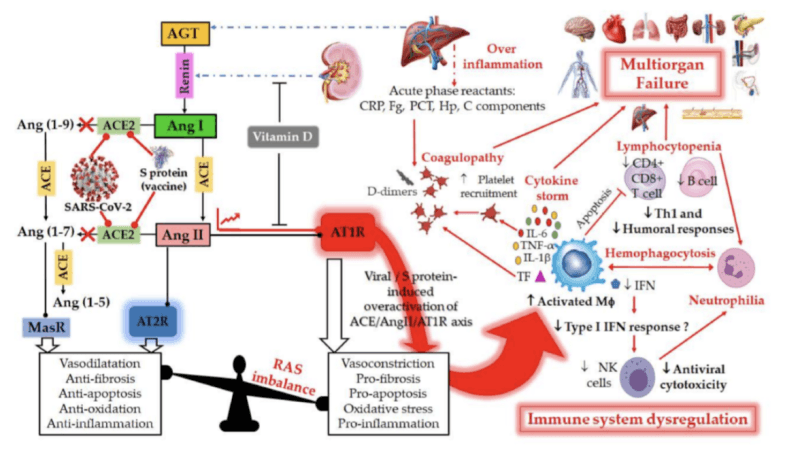

There is the risk that both the vaccines and the virus might cause similar harms to the cardiovascular system. Jean Marc Sabatier of Aix-Marseilles University has been warning against this from early in the pandemic. In 2021 he and his colleagues published a peer-reviewed paper: The Renin-Angiotensin System: A Key Role in SARS-CoV-2-Induced COVID-19.

The paper explains:

In fact, the viral entrance promotes a downregulation of ACE2 followed by RAS balance dysregulation and an overactivation of the angiotensin II (Ang II)–angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1R) axis, which is characterized by a strong vasoconstriction and the induction of the profibrotic, proapoptotic and proinflammatory signalizations in the lungs and other organs. This mechanism features a massive cytokine storm, hypercoagulation, an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequent multiple organ damage.

The model is depicted in Figure 1:

While the paper focuses almost entirely on Covid-19, the disease, the implications of the model go to risks of the vaccine also. This is cautiously slipped into the explication of Figure 1 (my italics): ‘during SARS-CoV-2 infection or upon receiving a spike protein-based vaccine, the viral Spike (S) glycoprotein binding to ACE2 receptor induces overactivation of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis.’

So, we must consider the risk that as well as the SARS-CoV-2 virus, some (if not all) vaccines might also induce overactivation of the ACE2 receptor and consequently the renin angiotensin system. There is no proof that they do, but there is equally no proof that they do not, and the model fits well with the Ip data on cardiovascular event incidence levels for the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines (but not with the favourable Moderna figures – what is different about the Moderna vaccine?).

This would be an issue under any scenario, but even more so if incidence of Covid-19 increases with the number of vaccine doses previously received. The vaccinated can be repeatedly challenged by the spike protein both in the form of the virus and in the form of the vaccines as well. The risks from infection are not obviated – the risks of vaccinations are added to them, not substituted for them.

There has been a torrent of papers on the effects of Covid-19 vaccination, focusing on these limited windows of effectiveness. They display strong confirmation bias – data and findings apparently supporting effectiveness are welcomed with open arms despite obvious flaws, findings that overtly cast doubt on effectiveness or safety are vigorously contested and often succumb to a campaign to have them retracted. If the data are unfavourable, better to ‘adjust’ them so you can reverse the conclusions. This constitutes scientific misinformation.

Although pro-vaccine papers sometimes have sophisticated technical values, they show little capability for strategic thinking.

Which is the preferable and lowest-risk strategy over the timeframe of the pandemic crisis:

- Undergoing multiple vaccinations of short-term effectiveness

- Minimizing exposure to the spike vaccine?

The scientific literature simply does not test this strategic comparison by comparing overall outcomes for the vaccinated from the point of vaccination to the end of the pandemic crisis period, compared with the truly unvaccinated. But what we do know from the Ip population-level study of England is that Dose 1 for the two most commonly used vaccines increased 11 out of 11 cardiac events and a booster increased both arterial and venous events again for the Pfizer vaccine.

Individuals should be free to make the strategic choice, guided by their health professionals, and should not be coerced to follow the first strategy through mandates. Mandates should not risk creating severe adverse outcomes on a mass scale.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.