At a recent Brownstone Institute event, I spoke on a panel about the importance of judging public health interventions by their real-world impact — by whether they genuinely help people live longer and healthier lives.

I had just written about mammography screening, and how decades of research show that while it detects more breast cancers, it doesn’t reduce overall deaths.

During the discussion, someone raised the issue about prostate cancer screening and the PSA test.

It was a fair question — because the parallels with routine mammography are striking. Both programs rest on the same seductive logic: find cancer early, treat it, and save lives. It sounds so obvious, doesn’t it?

But the latest data on prostate-cancer screening — 23 years of it — suggest that this promise, too, has failed the most important test: overall mortality.

When the Numbers Don’t Match the Promise

The European randomised screening study began in 1993 and enrolled more than 160,000 men aged 55 to 69. Half were invited to have regular PSA blood tests; the others were not.

After 23 years of follow-up, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the results are just in.

Predictably, screening led to about 30% more prostate cancers being diagnosed. However, most were low-risk tumours that never would have caused harm.

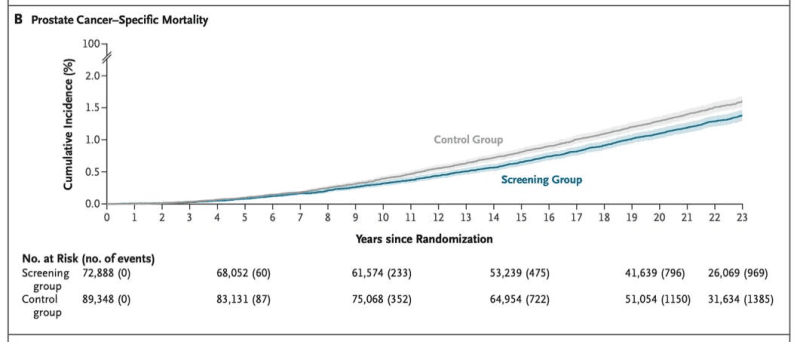

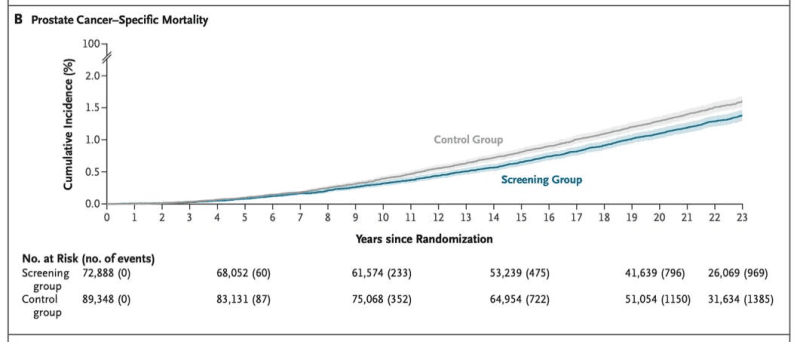

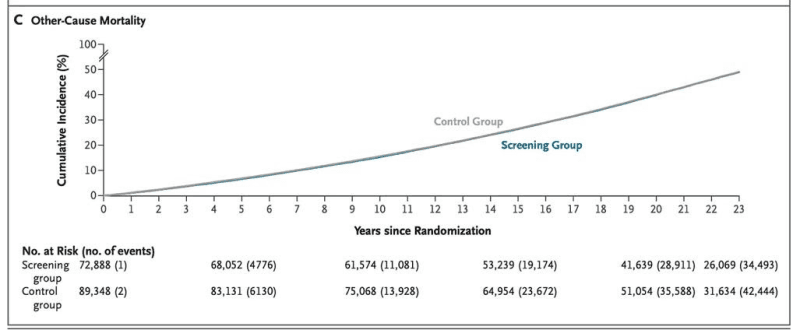

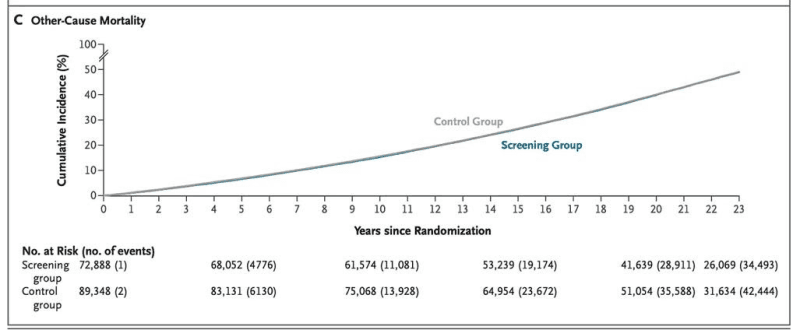

Men who were screened had a 13% lower risk of dying from prostate cancer than those who weren’t screened.

But that difference, while sounding impressive, shrinks dramatically when translated into absolute numbers: 1.4% versus 1.6%, an absolute reduction of 0.2% (see graph).

That means you’d have to screen about 500 men to prevent one death from prostate cancer — the other 499 see no benefit.

But here’s the key point — the overall death rates were identical in both groups (see graph below).

Despite finding more prostate cancers, men who were screened did not live longer — they simply had a higher chance of being labelled “cancer patients.”

The study found that while screening can modestly reduce prostate cancer deaths, it comes at the cost of significant overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

The reality for most men is that once a PSA test is positive, it’s almost impossible not to act.

At the Brownstone event, I described it like a conveyor belt: once you’re on it, it’s difficult to get off. An elevated PSA often sets in motion a chain of medical interventions that men may not need.

The Harms We Don’t Count

A positive test often triggers a chain reaction — MRIs, biopsies, surgery, radiation — and often with lifelong consequences.

Men who undergo unnecessary treatment can be left impotent, incontinent, or chronically anxious.

Most elevated PSAs are false positives, and even when biopsies reveal no cancer, the process itself carries risk — including infections that can require hospitalisation — and often leads to repeat testing and repeat biopsies.

The psychological toll — months of fear between tests, the dread of results, the pressure to “do something” can be harmful.

A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine of nearly a quarter-million US veterans found that even men with limited life expectancy — too old or frail to benefit — were being treated aggressively for prostate cancer.

The authors urged doctors to “avoid definitive treatment of men with limited life expectancy to prevent unnecessary toxic effects.”

It’s a roundabout way of saying what should be obvious — we’re hurting people we can’t help.

It’s often argued that today’s tests and treatments have improved, and while that may be true in some cases, the fundamental problem remains.

The Pressure to Participate

Every October brings Breast Cancer Awareness Month, urging women to get mammograms “for peace of mind.”

Every November brings Movember, encouraging men to grow moustaches to raise funds and promote prostate cancer screening in the name of “men’s health.”

The intentions are good. But these campaigns often create social pressure rather than informed choice. They send the message that screening is a no-brainer when, in fact, the evidence is far more nuanced.

Advocacy groups and celebrity endorsements can amplify that pressure, but they rarely explain the full picture: that for most men, prostate cancer is slow-growing and unlikely to be fatal.

Around 97% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer die from something else. For some, those are odds worth accepting.

Public health messaging tends to treat populations as uniform. But individuals aren’t.

Some men want every possible test and every possible intervention — and that is entirely valid. Others are comfortable with uncertainty, preferring to watch and wait rather than undergo treatment for something that might never cause harm.

Understanding what population-level recommendations mean for individual lives is essential.

Even Richard Ablin, the man who discovered the PSA test in 1970, later called mass screening “a public health disaster” in the New York Times, authoring an article titled “The Great Prostate Mistake.“

Why Informed Consent Matters

At the Brownstone panel, I stressed the need for true informed consent — not just a pamphlet or checkbox, but an honest conversation between doctors and patients.

I’ve seen PSA tests ordered without patients even being aware — bundled into routine blood work for “general health” or “annual checkups.” Too often, the first time a man hears about PSA screening is after an abnormal result.

Patients must be asked whether they want the test — and whether they understand what a positive result could set in motion. They should know the risks of testing, the risks of not testing, and what living with uncertainty might look like.

For a man with a strong family history or someone who cannot live with uncertainty, PSA screening may be reasonable.

But for someone at peace with small risks and wishing to avoid procedures that may lead to impotence or incontinence, declining screening is equally rational.

This is what evidence-based medicine looks like — it takes into consideration a patient’s values and preferences, together with clinical experience and data.

The role of a doctor is to inform, not coerce.

Public health must stop selling certainty and start embracing nuance. Some abnormalities don’t need to be found. Sometimes in medicine, ‘less is more.’ And sometimes the most responsible medical decision is to do nothing.

The point is, it’s patients — not governments — who should steer their own medical decisions, once they’ve been fully informed.

The story of the PSA test, like routine mammography, reminds us that well-intentioned medicine can cause real harm when certainty is oversold and humility is lost.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.