For all its obvious organizational authoritarianism and corruption, the Catholicism that reigned largely unchallenged in Western Europe in the ten or so centuries previous to the unveiling of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses in Wittenberg in 1517 was, and to a great extent still is, profoundly democratic in the way it looks at the intrinsic worth of human beings before God, holding that insofar as an individual decides to accept God’s grace, practice good works, and cleanse himself of sin through repentance, he or she can enjoy eternal salvation.

However, as Max Weber argued in his justifiably renowned The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), Protestantism, and more specifically its Calvinist variant, changed much of this through its propagation of the doctrine of predestination; that is, the idea that “only a small proportion of men are chosen for eternal grace” and that we humans, with our limited purview of creation are unable to discern exactly who among those in our midst has been called by to form part of this small cadre of God’s pre-chosen Elect.

While Weber was primarily concerned with how the anxiety created by not knowing the ultimate disposition of their souls before God often drove people to try and prove their elect status before others through industriousness and the accumulation of wealth, the doctrine of predestination had many other important effects on the populations (such as our own) where Calvinism took root and played a key role in generating foundational cultural norms.

Perhaps none of these is more important or consequential than the generalized acceptance of the idea that a select number among us, putative members of that predestined elite, not only have the right, but the obligation to correct and/or tame the moral comportment of their fellow citizens.

Like most people raised in the US, I assumed as a young man that this was a universal cultural dynamic.

But that was before I began my decades-long immersion in the cultures of Post-dictatorial Spain, Portugal, Italy, and numerous countries in Latin America, societies that Americans, raised knowingly or not on the many offshoots and variations of the Black Legend, generally see as being cruelly corseted by the supposedly restrictive and personally invasive diktats of the Catholic Church.

What I found, however, was the exact opposite of all that. I experienced cultures where the urge among self-selected seers to rise up in high moral dudgeon against the wayward comportment of others was largely non-existent, cultures where people young and old lived with their bodies, its basic functions, and their own sexuality with a naturalness and fearlessness that I had seldom known or seen growing up, cultures that, in the end, were deeply aware of the existence of puritanical priggishness of our Calvinistically-inflected cultures, with their self-appointed moral teachers, and often laughed derisively about it.

And unlike so many of us raised within the Protestant pale of settlement, the citizens of these places often had no problem recognizing the link between our “if-there-must-be-hidden-moral-paragons-among-us-they-might-as-well-be-me” outlook and the nature of contemporary Anglo-American imperialism.

They could clearly see that when all the military and economic accoutrements of imperialism are stripped away, what remains is its spiritual core: the imperialist’s deeply held conviction that the elites of his tribe are morally superior beings who thus have the right and the responsibility to “share” their enlightenment with the benighted non-Elect cultures of the world.

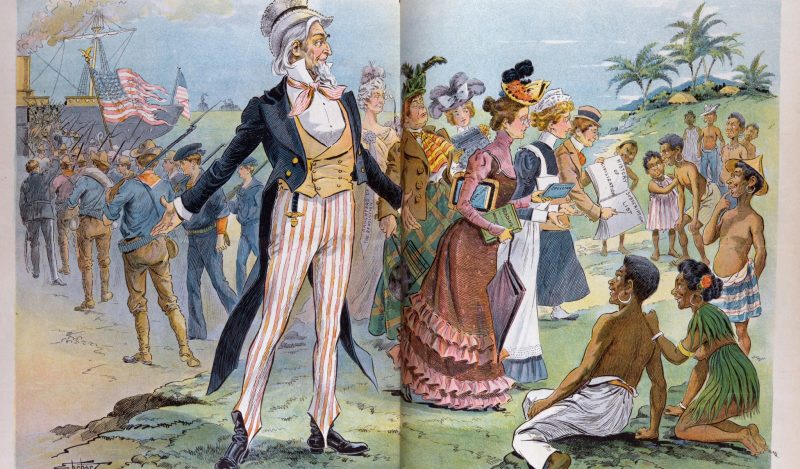

In this context, it was supremely fitting that it was Rudyard Kipling, an Anglo-American living and working during the early years of the shift from British to American global primacy, who propounded the concept of the “White Man’s Burden” in a now famous poem of the same name. In it, he speaks of the need to “wage savage wars of peace” against those living outside our bubble of superior civilization who are described in the text as “silent, sullen peoples” who are “half-devil and half-child.”

In the quarter century or so immediately following World War II, a time marked by the decolonization of many parts of Asia and Africa, Kipling’s testosterone-infused ode to the task of inflicting superior Anglo-American culture on lesser beings was generally presented as an embarrassing reminder of a now wholly eclipsed vital outlook.

But events soon showed this was not the case. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Anglo-American “obligation” to “wage savage wars of peace” on lesser others came back with a vengeance, but this time shorn of its vocabulary of overt disdain for its overseas tutees.

In the 1990s, Anglo-American leadership cadres, aware of the off-putting nature of Kipling-style discourses, began speaking of other people’s need for lessons in something called Democracy. Those who agreed to be tutored in the art of this endlessly flexible concept were granted the title of allies. Those who believed they had a right to pursue their own indigenous vision of the good life were branded extremists, or if they were especially recalcitrant in their continuing devotion to their obviously backward native ways, terrorists.

As the title of Kipling’s famous poem suggests, this practice of war-fueled moral beneficence was long an overwhelmingly male affair.

But thanks to the advances wrought by feminism we can now rightfully speak of the White Woman’s Burden as well.

Like their testosterone-laden forerunners, those assuming this honorable mantle possess a rock-solid belief that there is a moral elect embedded in almost every population whose job it is to liberate the majority from their weaknesses and superstitions through instruction, and if need be, loving coercion.

But unlike their male counterparts, whose ways of teaching and helping mostly relied heavily on physical intimidation, our new female pedagogues tend to trade much more heavily in things like interpersonal boundary violations and reputational destruction.

And whereas the violently helping spirit of our male elects was generally aimed at those outside their own grouping or tribe, our newly burdened white women elects are much more comfortable working domestically, doing things like declaring those long seen as being the necessary yin to their yang—men—as being per se toxic, which is to say, belonging irremediably to the cohort of the eternally damned.

And doing things like portraying the gift of fecundity, long seen as perhaps the world’s most precious commodity, into a regrettable curse. All this while fulsomely praising abortion and genital mutilation, something that only a few years ago many of their numbers decried as barbaric when it was being carried out by those lesser people in places like Africa.

And perhaps most remarkable and surprising of all, these zealous new bearers of the White Woman’s Burden have made remarkably rapid inroads into the Catholic cultures of Europe and America that only a short time ago reflexively sniggered at the male version of the north’s Calvinist busybodyism.

Today, you need only spend a few minutes in the Boho neighborhoods of Barcelona, Lisbon, or Mexico City, or listen to the media that both serves and is generated by people from those rarefied places, to imbibe today’s distaff descendants of the Minister of Geneva sharing their moralizing magic with the benighted masses around them.

Are we witnessing, as these moralizing maenads seem to think, a new beginning that will fundamentally reorder the nature of human relations down to the most basic and time-ratified drives and functions of our bodies?

Or are we observing the chaotic and pitiful end to the 500-year project of European modernity which was fueled in no small part by its embedded doctrine of Calvinist predestination?

If I were a betting man, I’d have to say the latter. Why? Because as the ancient Greeks told us with their stories of Icarus and Oedipus, man’s ingenuity and ability to transform his environment, while often prodigious, are in the end no match for the unimaginable creativity and power of the Gods.

My sense is that these simple lessons, which modernity has bent over backward to portray as anachronistically irrelevant to our circumstance, are about to reassert themselves in ways that few in our class of enlightened male and female burden-bearers ever thought possible.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.