Recently, Brownstone Journal published a short piece by Toby Rogers: “Society Without an Organizing Thesis.”

In it, Rogers briefly tours the dominant political philosophies spanning the past few hundred years and points out how each of them has failed us. Each attempted to solve problems left behind by the era immediately preceding it; and while each did, indeed, solve some problems and create new opportunities, each, in its turn, left a whole new suite of problems in its wake.

We are left, now, with a broken and fragmented culture, on the brink of institutionalizing a fascist dystopia as its principal ruling structure, and the competing socio-political alternatives have terrifyingly little to offer us. So it is no surprise — to me, at least — that Rogers speaks with flustered urgency when he concludes:

The urgent task for the Resistance is to define a political economy that addresses the failures of conservatism, liberalism, and progressivism while charting a way forward that destroys fascism and restores freedom through human flourishing. That’s the conversation that we need to have all day every day until we figure this out.

I feel the same, and I couldn’t agree more; for this happens to be the precise problem I’ve spent the last fifteen years (more or less) working on — and am currently attempting to finally write up into a cohesive narrative. So I thought I would take this opportunity to share some preliminary insights — as well as some of the experiences that led me to initially embark on this endeavor, more than a decade before the Covidian and post-Covidian era.

First, I should probably clarify something: I am not an economist. Toby Rogers is a political economist by trade — which is why he says we need to “define a political economy;” I am a philosopher with a background in behavioral neuroscience. I did not set out to “define a political economy,” but rather, to “coax out a social philosophy” — what I have previously referred to as “a restorative philosophy of freedom.” Yet, it will be quite obvious to anyone who has studied history, economics, and society that the domains of social philosophy and political economy are intimately intertwined.

They cannot be extricated. You cannot remove human psychology from any examination of what humans do; nor can you remove social philosophy from any examination of what humans do collectively. You can apply many lenses to this problem, and you can call it by many names, but what we are looking at — and what Rogers has also observed — is this: we are living in a socially fractured and disorganized world. There is little tying us together, in a cooperative way, to help us engage respectfully with each other while preserving human autonomy and dignity, and creating a flourishing and vibrant culture. It is causing socio-cultural erosion and vast degradation that is visible in almost every conceivable cross-section of our inhabited reality. And these are things that even our political enemies are observing.

Governments and institutions all over the world are assuming more and more powers over the minutiae of our daily lives; they are constructing an enormous infrastructure for the control, management, and social engineering of billions of human beings. Meanwhile, various social factions with competing ideologies and value systems, and an intensely seething hatred for each other, fight tooth and nail to acquire access to that emerging infrastructure, in the hopes of using it to vanquish their political enemies and exact “justice.”

There is a cultural vacuum. At various times throughout history, old and timeless truths need to be restated in new ways, and new frameworks also need to be developed that incorporate new understandings of the world and information into these old ways. The generations of the future need to come into possession of the tools and roadmaps that guided their ancestors, and to the extent that they encounter new frontiers or terra incognita, they may need to draw up new maps themselves.

But this has not really been happening, and to the extent it has, these new maps and translations have been mostly forged by people who are part of insular communities — who do not know how to speak with people outside their own echo chambers, and often do not even care to try — or, they have been forged by those whose scope and worldview is too narrow to properly incorporate the true scale, complexity, and diversity of the globally-connected “village” we now inhabit.

We are badly in need of some kind of social repair. We need tools by which to bring each other together again, to be able to create a vibrant, meaningful, living and cohesive culture, truly — perhaps, for the first time in human civilized history (if it is successful) — founded on mutual nourishment and respect for individual autonomy.

But, as Rogers points out, we cannot accomplish this by simply “returning” to the way things were in some previous era or by bringing back forgotten values. Why? Because the old ways of organizing society, both morally and culturally, did not work for everybody and will not work for vast numbers of people now. Ignoring or dismissing this reality does not make it less true, and would only inhibit the effectiveness of any new attempt to foster social cohesion.

It is easy to romanticize the past — especially a past that seems to represent our own utopian visions of the world, or to give preference to our personal ideas of beauty, comfort and morality. I’m as guilty of this as anyone. And there are certainly many incredible and worthy notions, philosophical ideas, norms, and traditions from nearly any era and location you could think of in history, which should be actively preserved and propagated.

But if we truly want to build a restorative philosophy of freedom — and with it, a restorative culture of freedom — if we truly care about freedom and autonomy itself, rather than just maintaining a desire to impose our personal visions of utopia on the world around us (and all of us should see clearly, by now, having studied and lived through some history, what a mess that is when anyone attempts to do it) — if we truly care about freedom and autonomy itself, we need to be able to transcend our own personal desires for the way we want to see the world, to take on the perspective of people who are our enemies, and to try to find creative ways that everyone could actually try, in practice, to achieve their goals and live in harmony.

If that exists, and is possible, then it will not look like anything that has existed before in the history of civilization. And we should honestly be happy about that, because each previous era of history has entertained its own gruesome social realities. But, it would very likely contain many elements of old traditions, values, and the things that have come before; or localized social microcosms where the romanticization and revival of past social orders may prevail.

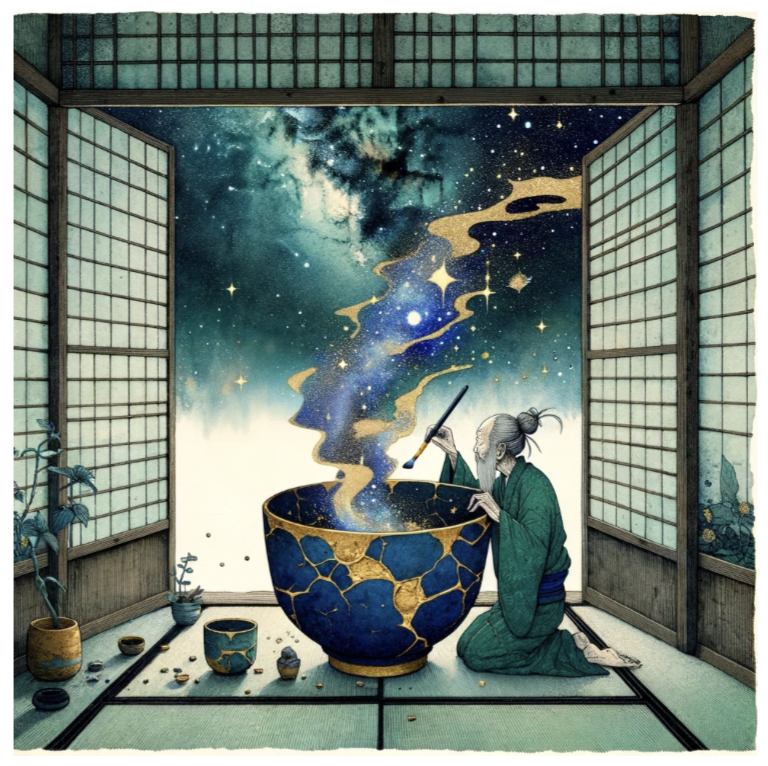

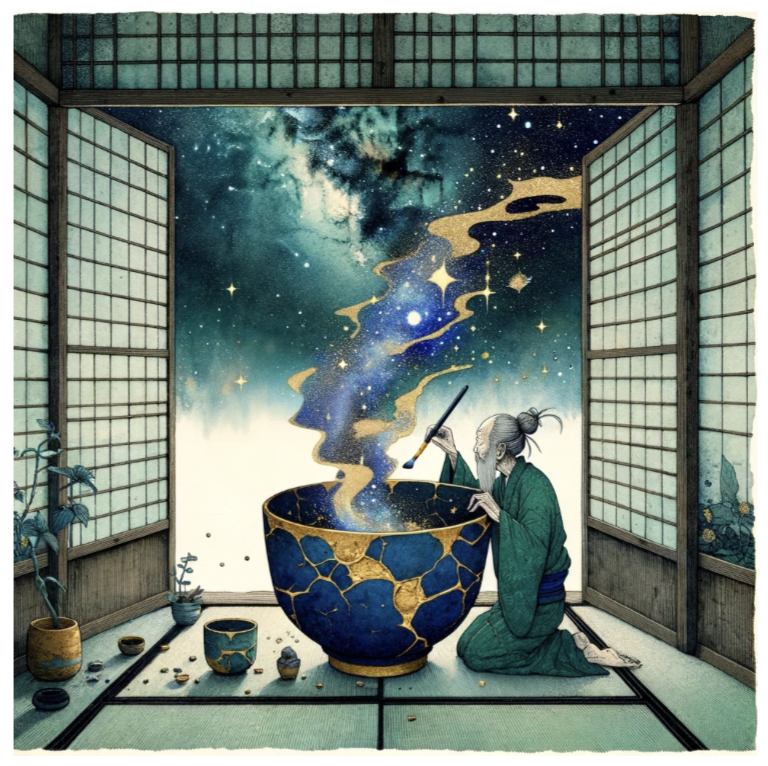

In Japan, the art of 金継ぎ (kintsugi) — “golden joinery” — or 金繕い (kintsukuroi) — “golden repair” — is an art by which broken pottery is mended using lacquer mixed with powdered gold. Rather than trying to hide the defects of the broken dish or vessel, and pretend the damage never happened, these defects are highlighted and utilized to increase the object’s beauty and elegance.

induced by the author for purposes of brainstorming and visualization.

I think this is a good metaphor through which to begin to approach our task. For if we truly do value freedom and autonomy, then this will be a collaborative endeavor, worthy of extreme humility in elaboration and in execution. It will largely be a work, not of top-down implementation, but of synthesis and mutual understanding. It will require actually getting to know what the world looks like beyond our preferred corner of it, and what other people around us want.

This is why I used the phrase “coax out” above, when talking about trying to explore the philosophy behind it. I do not see myself as an inventor or designer, and I am not trying to dictate anything for the world at large. Rather, I am trying to find what exists already, to synthesize it, and to see how various different perspectives or ways of life could be brought together in an organic and spontaneous way.

My goal is not, and never has been, to come up with some vast plan to re-engineer society or the world into compliance with my own visions — however noble I think them to be. In fact, that seems to be the exact attitude that, over and over again throughout history, has wrought enormous havoc on society and destroyed the beauty of the world and countless human lives.

I see my work primarily as a means of potentially beautifying something around me that has been horribly broken, and helping reunite the scattered shards into a new, organic configuration. And while most of us would probably agree, at least on the surface, with this sentiment, I think it really bears repeating — as often as possible — because it can be very difficult, even when we have the most noble of intentions, to resist the urge to try to become the Kings and Engineers of tomorrow’s utopia.

I have thought about this problem for a long time now. I have thrown myself into as many different communities, around the world, as possible, in order to expose myself to diverse perspectives, religions, philosophies, and methods of social organization, and to try to gain a broad understanding of the different types of ways that humans can, and do, build individual and collective lives. I do not claim to have all the answers. In fact, the more you learn, the more you realize how much you really just don’t know.

But one thing I can say: studying this problem has shown me the value of humility. We do not have a simple problem on our hands. There will be no simple answers, and it is not something that we can hope to hack together overnight, and then proceed to just roll out to the world. Therefore, I stress humility as a first operating principle for any approach to attempting to address this problem at all.

Below I will attempt to lay out — in no particular order — some of the questions, concerns, and potential leads that I have come up with over the years — partially through personal experience, partially through research into history and the mechanics of human psychology, and partially through engaging in perspective-taking and extensive thought experiments. I will share some of my methodology for reasoning, and how it has led me down the particular path that I have taken. This may ultimately span several articles.

Defining the Problem: Goals and Scope

Of course, I cannot tell you what, exactly, Toby Rogers means when he proclaims we need to define a political economy. I can only guess that he is talking about the same problem I have been trying to tackle, although he might choose to approach it from a different starting point or perspective. But that’s okay. I believe that, in any case, the problem he is trying to address shares a root with the one that I am addressing here. In that sense, at least, our goals have overlap. I will share my personal methodologies, and what I have set out to do.

The first step is to elucidate, and to make clear, the precise nature of the problem. It is one thing to say “We need to define a political economy” — or, in my case, “We need to coax out a social philosophy.” We can summarize the problem, in many different ways and from many different perspectives, just like I have tried to summarize it above. But it is quite another thing to ask oneself: “How do I go about trying to address this problem, in a functional way?”

And this is where goals and scope come in. What are our precise goals with respect to this problem? How big is our scope, and where in the social fabric does our scope apply?

I have seen many people take a practical approach to goal-setting: they assume that revolutionary goals are not possible; so they set out to change the system from within, or work within a field of pre-existing options. I am not going to tell anyone that can’t happen. In fact, I think that’s part of holding on to a proper sense of humility as we attempt to address this problem: we don’t actually know what can’t work, so we may as well be supportive of each other as we try to explore ideas and tactics from different perspectives.

But I have worked with some of these people. I helped my friend Joe Bray-Ali, a grassroots progressive candidate, campaign for a city council seat in Los Angeles. I saw firsthand how his campaign was sabotaged by his rival, incumbent Gil Cedillo, who has taken funding in the past from Chevron. Trying to change the system from within is a lot of exhausting work (I know — I was running around from door to door, day after day, talking to constituents on Bray-Ali’s behalf) in exchange for very little headway, for the most part.

That didn’t satisfy me. I wanted to approach the problem, not by trying to cut off one of its many hydra-heads (only to see two grow back), but by finding the real root, in the universally human and timeless patterns of history — and then moving outward, to more practical and concrete endpoints, from there.

Here is what I did to try to find this underlying problem:

- I kept a journal and meticulously wrote down everything I observed, throughout my day-to-day routines, that made me upset, or angry, or that came across as concrete instances of massive problems in our social fabric and infrastructure. Key here is that I started from my own experiences, and my own personal feelings about the world I had to engage with. I was not trying to solve anybody else’s problems, or change abstract political systems, or the world. I was principally concerned with living a fulfilling life myself — and finding a direct route to doing that.

- When I had a sizable list of these problems, I went through them and I tried to distill common underlying causes, in order to determine patterns. For example, getting fired from a job that you are not performing well (rather than being taught how to perform the job correctly), and purchasing a home appliance which breaks after only a couple months of use, could both be said to be examples of a “disposable attitude” in culture toward people and objects.

- I compared the patterns I observed with patterns that could be observed at different times and places throughout history, in order to understand how they are capable of changing form with time, as well as what characteristics remain universal and timeless.

I realized that a lot of the things that bothered me about the world I lived in, and made it a fundamentally uncomfortable and inhospitable place for me to make a home, boiled down to the following:

- The spontaneity of the individual will was being thwarted by extraneous societal demands, overregulation, and excessive imposition of order or inflexible rule systems.

- As a result, I felt like I did not have freedom to behave flexibly and to engage with the beauty and wonder of life in the way that felt most natural to me.

- I also felt that culture was becoming increasingly homogenized, predictable, and boring; what was lovable about humanity, and our natural connections to each other, were slowly being erased.

- At the same time, the world we lived in was incredibly complex, and increasingly so. Millions of moving parts depended on millions of other moving parts in order to function smoothly, and there was little room for error in many cases. Yet, no one person fully understood these parts, and most people had only an extremely narrow window into the actual mechanics of the world that they inhabited.

- Yet, people pretended to know a lot more than they did. They lacked humility. As a result, they were treating each other disrespectfully and disposably. Increasingly, people viewed each other as resources to be used, with little value for the beauty of expressive individuality. They began to have less and less respect, in turn, for the idea that anyone should have individual freedom.

- This led to a feedback loop, in which people insisted on more regulation and externally-imposed order, in order to keep others from behaving unpredictably and upsetting the fragile balance of this complex and increasingly-mechanized world.

- This regulation also increased the cost of living dramatically, as fees and permits and taxes began to stack up. As an example, I could not afford to start my own legal business in California, because the business taxes were $800 a year minimum, which I judged was too expensive for what I would expect to earn as a sole proprietor of a microbusiness.

- Furthermore, this regulation often placed one, or several, intermediaries in between a human being and the fundamental necessities and dignities of human life. The administration of national parks places an intermediary between ourselves and nature, along with natural sustenance activities such as hunting and fishing; excessive regulation of the food industry (in the wrong ways) places many intermediaries between ourselves and the suppliers of our food; landlords, the banks that handle our mortgages, local councils and homeowners’ associations place intermediaries between ourselves and our private dwelling places; and so on.

- These phenomena were self-proliferating; that is, they were not confined to one or two small regions, but quickly spread over massive territorial domains, making them difficult to escape or avoid, and alternatives difficult to find.

I valued my own personal autonomy. I wanted to work for myself; I wanted to wake up, and go to sleep, when I felt like doing so. I wanted to choose who my clients were, and how I interacted with them. I did not want to be told by someone else to “smile” when I didn’t feel like smiling. I wanted to own my own living space, and have permanent and lasting control over all aspects of it. And so on.

But I also fundamentally valued the autonomy of other people. I wanted to live in a culture where others around me were able to be spontaneous and empowered, to develop skills, acquire unique perspectives, and to do things in their own unique ways. I think this naturally enriches culture, and fosters a thriving society.

I asked myself: what kind of world would be my ideal world to live in?

And I tried to imagine it, and sketch it out, in detail. I imagined it without any restrictions — I went back to the drawing board of society. I imagined that everything anyone had previously told me about how “things have to be” or “things can’t be” was potentially wrong. After all, there has never existed, in human history, a true “utopia” — though plenty of people have insisted, in the past, that their ideas for utopia are the only possible way to organize society. Those ideas have almost always failed to work as planned.

So we don’t actually know how things “have to be” (because nothing has ever truly worked) and we don’t actually know how things “can’t be” (if they have never been implemented before, or, if there are potentially new ways to reinvent old ideas that have never been tried).

Once I had imagined a society that worked for me, and that contained all of the elements that were missing from my life, and that I thought essential to a fulfilling and meaningful existence, I moved on to the next step: figuring out how to navigate the disparity between my current reality and the world I wanted to see.

One problem was that my personal perfect world wasn’t going to work for everybody else. In order for me to obtain my visions, I would have to gain total power over the world and its infrastructure and people, and then enforce my vision so that it would become reality. In short, I would have to become a totalitarian dictator.

But I reasoned, starting from a place of humility: “I cannot ever be 100% certain what is right and what is wrong. I am a fallible human being. Would I really be comfortable imposing my ideas on other people, at their expense, and taking complete responsibility for that?” I realized I would not. “Therefore, I should not attempt to impose my own values and ideas on other people against their will.”

Furthermore, I reasoned: “All other human beings are also fallible, like me. If all human beings are fallible, prone to corruption and the lust for power in our own self-interest, then none of us can ever be 100% certain what is right and what is wrong. Given this, it is unreasonable and extremely arrogant for any human being to usurp authority over any other human being (except, perhaps, by mutual agreement, on a local and immediate level, or in self-defense).”

Note that I do not completely oppose the condition of top-down authority. What I oppose is the non-consensual imposition of this authority. Therefore, isolated communities organized in a top-down — and even potentially authoritarian — manner, if based on mutual consensus of the constituents, and if the communities were porous (that is, if you could revoke your consent and remove yourself from them, if necessary), could fulfill this condition. But global-scale, self-proliferating, and non-consensual, communities of this type (that is, empire-type or imperial powers and authorities, as well as the traditional structure of the modern state, which is based on an imaginary, non-consensual “social contract”) I opposed.

I made autonomy my foundational principle, and I asked myself if a truly autonomous world was possible. Would it be possible to discover a social philosophy, or to foster the development of a mode of social organization, that allowed for the autonomy of all individuals, without the necessity for global, top-down imposition of specific sets of rules; and would it be possible, at the same time, to preserve a sense of social order and harmony?

Would it be possible to create a social world that was not a zero-sum game; where some people didn’t always have to lose in order for others to win; and where people of all types could find a place and coexist with each other, while preserving what was important to each of them? And crucially — in order to preserve my fundamental principle of autonomy — would it be possible to foster such a development without a violent revolution, and without coercive, top-down, imperial force?

That is, would it be possible to create the kind of world I imagined without violating the fundamental organizing principle of that world in the process of creating it?

Many people would tell me that I was crazy, or idealistic; that such a world would be impossible. Almost every social philosophy — with the exception, perhaps, of sects of radical libertarianism and anarchism — accepts, at its foundation, that in order to preserve social order, autonomy must be limited, from the top-down, through coercive means.

That is because there is a fundamental perceived paradox between human autonomy and social order. If people have too much autonomy, it is believed, then they will violate the social order, or the rights and autonomy of others, in their own self-interest.

Yet, at the same time, if the imposed social order becomes too restrictive, people will become unhappy, and they will rebel, and resort to criminal means of achieving their goals.

However, I realized that violations of the social order have happened in all scenarios of social organization; there has never been a society that has been completely free of this. So we cannot use occasional violations of the social order as a pretext to limit human autonomy from the get-go; top-down limitations on human autonomy do not eradicate such violations, and it is not clear that they always (or, even, usually) reduce them.

Moreover, there are many small-scale social environments in which coercive force is not necessary to maintain social order (more on this later). Social cohesion can be fostered without authoritarian or excessively punitive measures, and often such measures only serve to undermine that cohesion and create increased unhappiness. Could it be possible to replicate such situations at larger scales?

I wondered if, by utilizing natural mechanics of human individual and social psychology, it could be possible to create a world where social coercion was not necessary to maintain social order and harmony, and where individual autonomy would be valued equally with social order and encouraged to flourish in a spontaneous and organic (i.e. non-manipulative) way.

I do not know if this is possible. But crucially, neither does anybody else. And usually, the people who argue most vehemently against its possibility are the same people who lack the imagination to come up with anything truly new or interesting themselves. Such people will not propose any new ideas, or even present particularly strong arguments in their own favor; they will merely tell you why things have to be the way they currently are, or why we must accept a currently-existing option that they happen to already prefer, for personal, ideological, or political reasons.

I refuse to accept that just because we cannot currently see the path forward to an imagined goal, that makes it impossible. I refuse to accept that, just because someone cannot personally imagine something, it is not worth pursuing. And I refuse to accept that, just because something sounds lofty or difficult, we should give up without ever trying. The great minds and revolutionary thinkers of history certainly would not have accomplished very much if they thought this way.

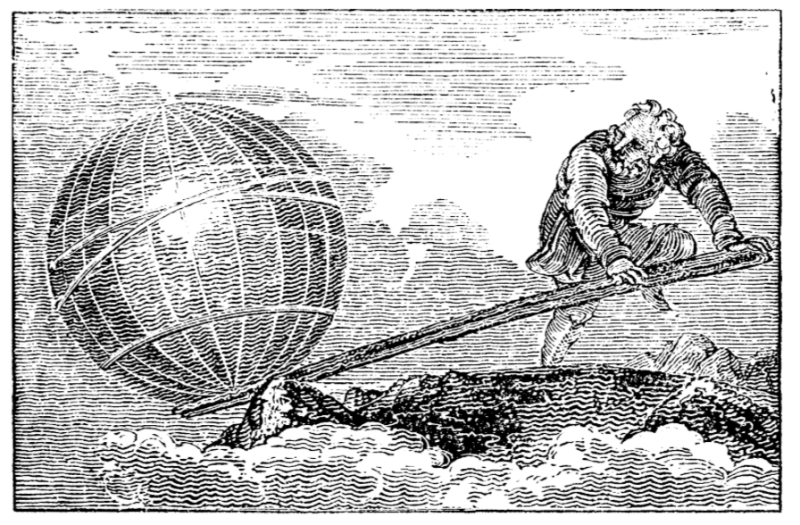

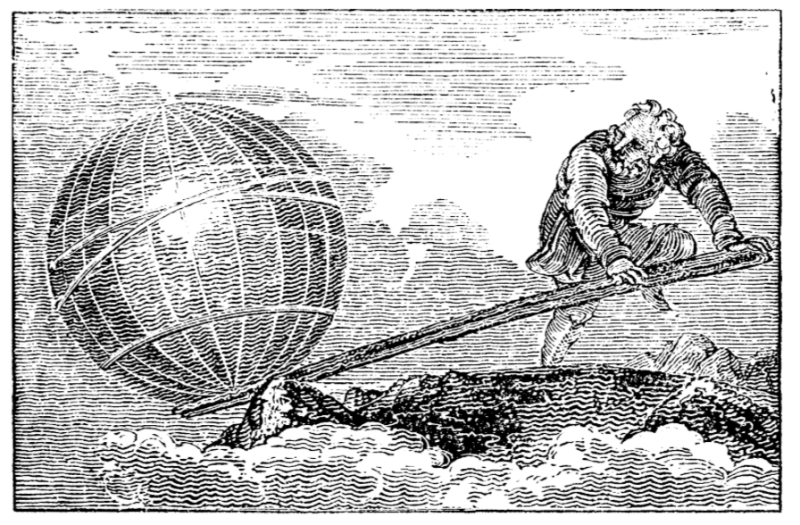

As the brilliant mathematician and inventor Archimedes famously said, “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the earth.”

Original Greek: “δός μοί (φησι) ποῦ στῶ καὶ κινῶ τὴν γῆν.”

I decided to pursue a lofty goal. And if I failed, who cared? At least I would probably accomplish more than what I would accomplish if I set my sights on lower ends to begin with.

But I also realized I was not as crazy, in reality, as many people might have liked to make me feel. For one thing, many of history’s most well-remembered geniuses attempted things that, in their lifetimes, were considered to be impossible. And — especially in the realms of technology and mathematics — intelligent and respectable people sat around contemplating problems (and were occasionally paid by universities or wealthy patrons) that would have been considered, by the average person, to be ridiculous or useless lines of thought.

Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci developed a concept for a flying machine that presaged the invention of the helicopter. Over five hundred years later, engineering students at the University of Maryland finally brought his design to life. And mathematician John Horton Conway discovered a connection between the so-called “monster group” of symmetric structures, which “exists” in 196,883-dimensional space, and modular functions (which he playfully called “monstrous moonshine”). Decades later, string theorists are utilizing his abstract conjectures and discoveries to attempt to learn more about the structure of the physical universe.

Sometimes, throughout history, the dreams and reasoned conjectures of visionaries sit dormant for decades or even hundreds of years before their ideological successors are able to make use of their findings. Their names may, on occasion, disappear from the pages of history books forever, but their silent influence spurs on the imaginations of many of our most well-honored innovators and creators. The minds of history’s most fantastical and lofty dreamers, be they today remembered or forgotten, have lit fires in the hearts of those who actually took center stage to move real pieces on the world’s chessboard.

But most of these creative and innovative thinkers tend to dedicate their pursuits to questions of technical ability, power, military prowess, and rational knowledge. Even the United States government, through the Central Intelligence Agency, funded lofty and ambitious projects, utilizing some of the country’s top minds, to search for techniques for brainwashing and mind control. Why, I wondered, did it seem so few inventors and innovators throughout history dedicated themselves to advancing the flourishing and spontaneous beauty of the autonomous human soul?

I grew up admiring the great minds and divergent thinkers of history who had pushed past the ideological limitations and narrow worldviews of their eras to imagine the impossible — even if, often, they were ridiculed by their contemporaries, or their ideas never came to fruition. I knew that I would rather spend my life pursuing an imaginative, lofty goal — even if it brought me zero recognition and resulted in a dead end — than to simply walk the paths that others had paved before me. I chose to hope that something new and incredible might be possible, if only someone (or, ideally, multiple someones) would dedicate enough time and effort to the task of trying to understand it.

So, if I can recommend humility as a first operating principle for elucidating a restorative philosophy of freedom, then I would suggest a second be: extreme open-mindedness of the imagination.

We should be willing to consider old problems in new ways; to have open and honest conversations with people we might have previously considered to be our ideological enemies; to question everything, even our most fundamental assumptions about the world; to be willing to learn from anyone; and to think of creative ways of utilizing and translating ideas we come into contact with. We should let go of the fears we have of ideas that previously scared us; and consider everything with an open mind and a generous heart. Then, we can begin to have real dialogue, and find ways to connect across society’s major ideological fracture lines.

We have talked about goal-setting. My goal was to see if I could pursue the seemingly-impossible task of elucidating a path toward a society founded on individual autonomy, which did not sacrifice social cohesion and harmony. But there are many possible ways to approach goal-setting. My goal is an abstract, and visionary, one. I am concerned, like a mathematician studying higher-dimensional shapes, with figuring out whether something might be possible, and if so, what it might look like.

Goals can range from more abstract and philosophical, to more direct and concrete. But it’s important to know, as precisely as possible, how one’s goal is related to reality, and what the implications of that relationship are with regards to its functional pursuit. When people gain an understanding of this, then it is possible for people pursuing different goals, at different levels of the problem’s structure, to communicate more effectively and to pass relevant information to each other about their insights.

With that in mind, let’s move on to address scope:

What is the scope of the problem?

This means, how much of reality are you trying to influence and affect? When we say, “We need a restorative philosophy of freedom,” what are we talking about? Do we want a single, unified, global philosophy that everyone subscribes to? Or are we just trying to gain hold of the reins of societal power until we get what we want? Is it okay if not everyone accepts the underpinning philosophy or narrative? Is it okay if there are active opponents to the philosophy or narrative? Is it okay if there are multiple interpretations to its on-ground implementation? If so, how should disputes between these interpretations be resolved, in case they clash?

Or do we mean to say, “My nation needs a restorative philosophy of freedom,” “The European Union needs a restorative philosophy of freedom,” “My state needs a restorative philosophy of freedom,” or even, “My neighborhood needs a restorative philosophy of freedom?”

From what end do we desire to change the world, and how thorough does it have to be? Are we approaching it from top-down? From bottom-up? From our own, personal, local sphere, moving outward? Do we want to change the whole world, or just our local areas? Or just the minds of people on X? Or our family and friends? And if we only want to change our local areas, then who are “we” as a social group? Readers, writers, and philosophers of Brownstone Journal, and our allies and affiliates, live all over the world. Do we want to help each other propagate a seed philosophy, or set of seed philosophies, across different locations, in the common interest of all of us? If so, what does that look like?

Here is where I find it helpful to implement at least two “states of imagination:” “idealized society,” and “real society.”

In “idealized society,” everything goes. You can have your own fantasy world, exactly as you want it. You can play around with redesigning everything from the ground up, your way, and “simulate,” so to speak, different outcomes, processes, or events. You can pursue liberating thought experiments. You can create your own personal fantasy, or try to create an idealized society from the perspective of different social groups (or of everyone).

In “real society,” though, we take the world as it currently is, and look at how we might plug into where we currently are and try to make a concrete, and immediate difference. Actions have real and serious consequences, based on actual configurations of people, objects, power sources, and systemic structures. In “real society,” you are not King (or Queen); other people exist, and have a right to weigh in on courses of action (I hope).

Obviously this is not a perfect dichotomy. It is more like a spectrum. But it is easy for us, in our minds, to get confused, or lose track of where we are on that spectrum. And it can create a lot of frustration and anger, when we attempt to apply our idealizations out-of-the-box to an imperfect real world; it can also hinder effective communication when many different people are visualizing the problem at different levels of these spheres, and don’t understand how their conversation partners are attempting to conceptualize their own visions.

In my experience, it is helpful to create a personalized fantasy of an idealized society for yourself. We all have this urge, to some extent, to remake the world in our image. But most of us can also recognize that there are major problems with this urge, when left unchecked, in concrete practice. If we do not have an outlet for our personal fantasies, to explore them with the full knowledge that they are fantasies (and therefore, to place limits on them), we risk behaving much like toddler “child-kings,” who, ignorant in the ways of actual, large-scale adult reality, nonetheless throw tantrums and proceed to try to boss their friends and family around and to conduct the universe in accordance with their whims.

Induced by the author for purposes of brainstorming and visualization.

I have met people who behave this way — full-grown adults, with established careers and many years behind them; they say things like (real quote): “If I was King of America, I would establish a Department of Facts, to determine what was true and what was false; and it would be illegal to disseminate anything false, on pain of prison.”

The person who said this to me was not willing to engage in a real and nuanced dialogue about the implications of censorship and its impact on real people. He did not separate his own personal societal fantasy from a world based in reality that included other people, along with their desires and needs.

Creating personal fantasies also allows us to get to know ourselves better, and to root ourselves with confidence within an understanding of what it truly is we want. We may be able to explore potential conceivable alternatives, or multiple ways that we might be able to achieve the same underlying essence of what it is we are looking for. If we can then place definite boundaries on these dreams and visions, we can go out into the real world and talk with people about diverse — and perhaps, scary — ideas, without feeling directly attacked or threatened by notions that seem to contradict them.

Often, when people make idle comments — on social media or otherwise — that tend toward the drastic, and are motivated by an intense surge of emotion, they are bringing an “idealized society” into a dialogue implicitly anchored in the real. But without a well-developed ability to clearly differentiate between these visions of reality, people can easily end up aggressively insisting on extremely ignorant and vicious social policies that disregard the rights and fundamental humanity of millions of their fellow human beings. If these aggressive lines are repeated enough, mass social delusions may end up forming as people normalize the idealized reality at the expense of the “real,” and eventually, horrific atrocities can ensue.

I set up for myself, to start, an idealized personal reality: that is, a whole world and universe that would be delightful and comfortable for me. This reality I envisioned mostly as an outlet for my own personal desires, and as a way to explore myself and gain better self-understanding.

Then, I asked myself what other people wanted. And I set up another idealized version of social reality: one in which other people could also coexist with me. I set as a stipulation that any time I encountered someone who had a philosophy that was inimical to my own, whose values conflicted with mine, or whose ideals made me feel angry or threatened, I had to include them somehow in that idealized version of reality, in a way where they could pursue a fulfilling and autonomous life.

This “idealized social reality” was the perfect society, built on my foundational principles of autonomy. I set the conditions as follows:

- Specificities of legal reality, or social rules, are not imposed by any global-scale, empire-like, or self-proliferating, non-consensual top-down institutional structures.

This allows for the possibility that such global institutions or organizations may exist; but if they did, their purpose would not be to create or influence specific laws or policies that are valid everywhere, or to administer justice. This would be a job for lower levels of the social microcosm. - Any social institution or organization with hierarchical authority to impose laws, administer justice, or govern other human beings and individuals must be established through the mutual consensus of all members of the social system — a real social contract. Individuals who do not give their consent must be free to either coexist within the system under their own autonomous aegis, or they must be free to leave the system to establish a life elsewhere.

I realized that some people actually do like hierarchical systems, and are followers by nature. In order for me to preserve my principle of autonomy, therefore, I would paradoxically need to allow that some people will want to live in non-autonomous social systems: for example, under monarchies, chiefdoms, or even dictatorships. Therefore, I had to be able to incorporate this into my model. - All individuals are autonomous and have the right to personal, as well as bodily, autonomy in all affairs, without coercion. No one is forced to believe anything, follow any particular path, etc.

This means that there would need to be places that exist outside of, or beyond, urban centers, dense communities or “societies,” where individuals who need to leave a community system can retreat to develop their own, or extricate themselves from interdependency with, and subjection to, others. In order for this to work, people would need open access to undeveloped land, and they would need to be able to engage with, and utilize, the resources there for their own sustenance and survival. Access to these places could not be gatekept by overarching institutions. - Social harmony exists. Perhaps we have not totally eradicated violations of the social order, but a general balance exists which keeps the world, as a whole, functioning smoothly. Again, it may not be perfect, but then again, neither is anything else; the point is that the system as a whole self-balances and self-corrects, and mass-scale violations of autonomy or order are prevented from occurring by those balancing forces.

I realized that the main problem throughout history has not been that people commit crimes or sins, do bad things, or correspondingly, suffer from the deeds of others. Human social designers and philosophers have tried to eradicate these occurrences in their societies for thousands of years. But none have been completely successful. And it is perhaps safe to say that more atrocities have been committed in the name of this eradication than in the absence of such attempts.

The worst tragedies, by contrast, are recognized because they happen on a mass scale, and often, predictably: a nationality or race is targeted, with predictable regularity, because of their accent, traditions, or skin color; a genocide is committed; a war turns thousands of healthy young men, with families, into cannon fodder; an authoritarian dictatorship murders millions of its own citizens; a mass shooter fires into a crowd at a school or a concert; a particular neighborhood is “scary” because it is home to several gangs, and has a higher-than-average murder rate.

I reasoned that huge, large-scale, self-proliferating top-down institutions of authority provide a sort of infrastructure for the management and control of human beings, usually with the stated aim of preserving social order. This infrastructure — while often planned out, in the beginning, to maximize human rights and dignity, and minimize the risk for corruption — almost always falls into the wrong hands and ends up perpetrating violence, imperialism, and injustice. When this happens, it occurs on a scale far larger than any individual criminal could accomplish, and often with far more consistency and regularity.

Yet people often use criminal behavior and human selfishness as the justification for these institutions in the first place. Since we cannot eradicate this behavior (or at least, we have not succeeded in doing so, even under the most authoritarian and controlled conditions), we should not use the fear of it as a justification for risking even greater atrocities, by putting immense infrastructures of power into the hands of corruptible individuals.

So I accepted that occasional violations of the social order will, likely, occur, and I asked myself: is there a way to foster balancing or harmonizing forces that would minimize these, or at least keep them from gaining ground on scale and regularity? - In addition to social harmony, human beings exist in harmony with other beings, their environment, and the natural world.

Here I do not stipulate a kind of primitivism, a total absence of technology, or a destruction of civilized modes of social organization. I also do not stipulate that humans should refrain from eating meat, or altering their environment in any way. In fact, one of the questions I set out to address was: might it be possible to preserve civilization and allow for the use of (even advanced) technologies while meeting this condition?

But I do think it is important for us to respect the world that we are a part of, rather than to simply use it as a resource. This is a topic for another time, however.

I decided I would not try to “design” the entire social system from the top-down. In fact, my stipulations demand that I not attempt to do this. If people are truly autonomous, I cannot design the specifics of the society; only the initial conditions. I cannot prevent people, of course, from creating individual social microcosms in this world that allow for extremely authoritarian and coercive societies; and that is not my goal (as long as those microcosms do not gain total or widespread control).

But there is an obvious challenge: after setting a world with these initial conditions, over time, empires and authoritarian top-down systems will almost certainly develop. Some people will always emerge as Machiavellian parasites and manipulators. They will want to dominate increasingly large territories and subject them to their own will. And any attempt, from the top-down, to rein this in, risks becoming the very thing it was established to prevent.

Furthermore, it is very common for people, in the heat of conflict, to come to a stalemate with regards to the boundaries between each others’ rights. Some people will always see as “theirs” what rightfully belongs to other people; and vice versa. Sometimes there is no real “correct answer,” either, to a social problem, and negotiations break down.

The challenge here is the question of coexistence and social negotiation. How do people with different perspectives on justice coexist in peace with one another? And how can people who discard the notion of justice altogether, serving themselves at the expense of others, be prevented from gaining a foothold to large-scale control?

This is a question that all modes of social organization need to contend with. But most choose to solve it through the use of coercion. That is, they try to combat the weaknesses of human psychology through external structures, and by creating artificial chains of consequences that attempt to incentivize desired behaviors, punishing undesired ones. I asked myself: would it be possible to address it, instead, from within — by harnessing the natural strengths and positive rhythms of human psychology?

This is the next question I set out to answer — though, as this piece is already running long, I must save it for a follow-up.

Let’s close by giving a briefly-sketched overview to the implementation of my imagined “real society.”

If I’m starting from the idealized society I outlined above, this is a far cry from the world we currently live in. We have numerous top-down authorities and institutions, which rule over vast areas in complex and overlapping ways. Self-preservation is an incentive for these institutions, once they are established; anyone who wants to try to dismantle them is generally seen as an enemy to be eradicated. They no longer serve the interests of the people at this point, but of themselves. And “they” are not human beings, but impersonal entities.

In addition, society is currently split along many fracture lines, and individuals have strong and often conflicting — and more importantly, totalizing — opinions and ideas. The totalizing element, for me, is more important than the conflicting element; remember, in my idealized society, people can coexist while holding different conflicting ideas, or modes of social organization (we can examine later whether this might actually be possible). But a totalizing philosophy requires that everyone else do what you say — it is the philosophy, in short, of the Child King (or Queen).

The totalizing philosophy does not restrict itself to a given localized territorial domain; it needs to encompass everything, or else eliminate whatever it cannot incorporate. It is a narcissistic philosophy; the self is all there is, and nothing is allowed to exist outside of it.

We currently do not exist in harmony with each other or with our environment. I asked myself: “How do I go about plugging this idealized society into the real society in a way that does not violate my operating principles, and that genuinely respects the other beings that form a part of this society?”

My stipulations are as follows:

- I cannot violate the autonomy of anyone else, or impose anything on anyone against their will, or through coercion or manipulation.

- I am restricted by actual realities: i.e. my own access to resources, my geographical location, my social networks (both online and in person), the opportunities I have available to me in my environment, and respect for the desires and needs of people around me.

I realized this implies a couple of things:

- I can’t depend on large numbers of people accepting any philosophy that I develop; rather, I need to develop a philosophy that is mutually interchangeable, translatable, and compatible with existing philosophies around me, in order to facilitate effective communication without the necessity for manipulative “propaganda,” war-like behavior, or aggressive sales tactics.

Any strategy I develop, therefore, needs to allow other people to hold on to their pre-existing perspectives and ways of interacting with, and seeing the world (we will see why I find this to be true later). - If existing top-down institutions and authorities are dismantled, or reorganize themselves, it needs to happen without the use of violence.

- If I cannot attempt to physically force or coerce, or covertly manipulate people (i.e., as in the Bernaysian sciences of public relations and advertising, or “behavioral nudging”) into accepting my ideas, or trying to create the society that I envision, then the mechanism for change needs to be through inspiration and by encouraging natural mechanisms of human psychology to align and harmonize organically.

To that end, as I stated above, I see myself as less of a social designer or behavioral engineer, and more akin to an artist of kintsugi — helping to fill the cracks in our broken culture with lacquer of gold, to inspire others and to highlight, with love and with beauty, the possibilities that exist but have heretofore been ignored, or lie dormant.

Or perhaps as a lightkeeper, in a lighthouse, shining a beacon so that the ship of the heart can find where to sail, without dashing itself on the rocks.

Throughout much of human civilized history, it has been the fear of others that has governed the bases for our social philosophies, modes of government, and our political economies.

We fear the average man; we fear our neighbor; so we insist we need enormous, top-down, centralized institutions of power to “rein in” his or her destructive, selfish tendencies, and preserve the social order.

People are unwilling to contemplate a life without such systemic entities and institutions — which always bring with them the risk of large-scale corruption and the abuse of authority — because they are afraid of what their individual fellow man will do in their absence. But they are completely happy to accept these greater, harder-to-eradicate, larger-scale risks, on the other hand.

They turn a blind eye to the bombs dropped by their governments on thousands of people in far-distant lands, while clamoring for increased restrictions on the autonomy of their terrifying and unpredictable countrymen, in the name of “safety” and “public order.”

When those restrictions fail to work — just like with the Covid crisis — they clamor for more, implemented faster and harder, rather than questioning whether coercion is the correct strategy at all.

Like child-kings-and-queens, they know very little about the vast world, and the true effects of their clamoring; but nonetheless, they insist with vigor and emotional intensity that “this is the only way.” And they respond to the failure of their whim to work its will upon the world by simply trying old and tired tactics more aggressively.

But perhaps in the darkness of the night, and in the space between the cracks, lie possibilities that have never been tried, and which might open up new worlds to us. If only somebody would shine a light on those dark spaces, and paint the cracks so lovingly with gold, to highlight what has lain invisible or forgotten for millennia.

induced by the author for purposes of brainstorming and visualization.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.