Preface and Executive Summary

More than thirty months after the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 on the world stage, it is time for the public to evaluate America’s response to the virus, with a particular focus on economics.

Both the virus and our policy decisions taken in response to it have taken a toll on America.

In the US, children’s mathematics and language abilities have reduced markedly, particularly among the poor, while worldwide, over 600 million children have been negatively affected by school disruptions. World food prices increased nearly 60% between May 2020 and March 2022, disproportionately affecting the poor in the US and elsewhere. Depression and anxiety rates have increased by at least 25% in the US and around the world.

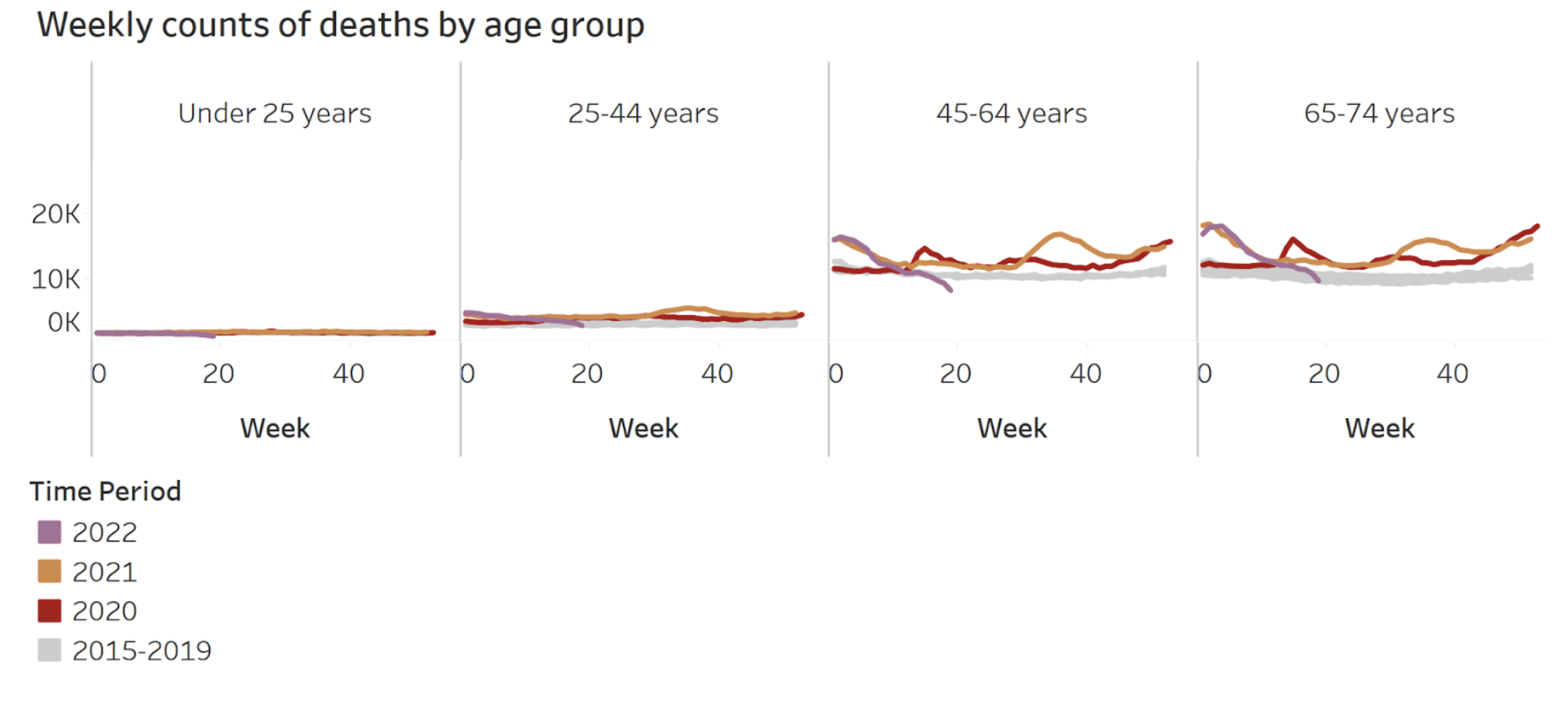

Government debt in the US has increased by at least 30% of GDP, compared to an increase of only 6% of GDP in Sweden. US inflation is near 10% as of early 2022, and similar rates of inflation have arrived in many other countries that massively increased spending, but not production, during the Covid period. In 2020 and 2021, roughly 7 million people died in the US, with 10-15% of these deaths attributed to Covid.

How much of the health and economic damage witnessed in the past two years is due to the virus itself, and how much is due to our policy response? Public rhetoric is now implicitly attributing economic harms and social dislocation to “the pandemic” (i.e., the virus itself), whereas data indicate that much harm and dislocation have resulted from man’s inhumanity to man as embodied in our policy response. This then implies that an evaluation of our policy response can yield insights applicable to guiding our handling of future threats similar to Covid.

In this essay, written from a broad economics perspective that incorporates an understanding of incentives, institutions, information, and power, we address the following three broad questions: (1) What were the roles and responsibilities of our institutions when faced with a threat like Covid? (2) What were the costs and benefits of the response that transpired? (3) What is the need and potential for institutional and social reform? The overarching aim is to raise questions and suggest initial ideas that investigators and researchers can use, rather than to give final answers.

Roles and responsibilities in government

As SARS-CoV-2 emerged, many individuals and groups played a part in crafting the governmental response at the federal, state, and local levels. When the broad response was set, which people and groups both within and outside of government were ultimately responsible for which parts of the decisions taken, and was a different overall response politically feasible at the time?

How were the viewpoints of the various professions (doctors, lawyers, psychologists, economists, schoolteachers) and bureaucratic departments (trade, education, immigration, health) expressed and integrated into the whole-of-government response? Did the response adapt over time to changing information (e.g., uptake of new early treatment options, adjustments to modeling simulations as new data on transmission and lethality became available, adaptation to new information about the efficacy of masking, incorporation of emerging knowledge of collateral damage)?

We lay out a stylized framework of how the system as a whole was supposed to function, a brief overview of how various groups and institutions actually functioned, and lines of inquiry to reveal how the actual response we witnessed came about.

The role of economics

A particular area of focus is the role of economists and the economic perspective in driving the policy decisions of this period. The economic perspective recognizes the interdependence of sectors, workers, countries, and activities, and acknowledges that the ability of a modern society to produce human welfare results directly from the coordinated functioning of millions of individuals taking countless daily decisions influenced by local information and incentives to which no central authority has access.

Concern over the economic impact of the pandemic response, expressed by economists cognizant of the life-giving potential of a healthy economy, came to be particularly deprecated in the popular press and in the public mind during Covid times. Those who raised the problem that “shutting down the economy” might have deleterious impacts on public health and on our way of life generally came to be denigrated as putting money ahead of lives, or choosing profit over people. Those who raised the standard economic perspective of trade-offs, wherein a choice to spend on one thing also means a choice not to spend on other things, and wherein a decision to halt the normal operations of businesses, communities, or hospitals creates victims of its own, was pilloried.

How did it come to pass that two key lessons of economics – that the economy is the source of our livelihoods, and that there are trade-offs – were so disregarded? How did the idea of “pressing pause” on the economy come to be seen as feasible? Were economists asked to consult with decision-makers? If so, did those asked in fact contribute, and did they provide the economic perspective described above? If not, why were they not asked?

Costs and benefits

Large disruptions emerged from our response to Covid in many areas of social and economic life. The results of the Covid response are now being seen in global goods shortages, dislocations in health-care delivery, a reduction in the cognitive and emotional development of our children, and hunger. Inflation is rising alarmingly, a direct result of supply-chain breakages and central bank policy. All of these effects relate to economics and to our economic policy choices, underscoring the point that the economic perspective is not focused only on narrow concerns about financial markets, but on the whole of social functioning.

Over the course of the pandemic, research worldwide has shown that these costs are largest in the following areas:

- Mental health reductions (particularly in the young);

- Health neglect for non-Covid causes resulting from a reorientation of the health service to focus heavily on Covid (including the halting of services essential to life, such as IVF services deemed to be inessential during this period);

- A greatly increased debt burden on the state, implying reductions in future government services;

- Increased idleness of production factors, including business closures and a decrease in labor force participation;

- Disruption to human capital accumulation and the cognitive and emotional development of the young;

- Disruption to markets and the price mechanism (inflation, supply-chain disruptions, impediments to consumer choices via movement restrictions, mandated changes to business operations);

- Increases in income and wealth inequality, and reductions in opportunities for the disadvantaged.

These costs may or may not have been appropriate and necessary. To assess the need to pay these costs in order to address Covid, we need to estimate their value and compare that to the benefits that may have been achieved by the Covid policies that produced these costs.

We follow a method for assessing the costs and benefits of America’s Covid policy response that takes seriously the statement in the Declaration of Independence for the inalienable right of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This means the state implicitly has a duty both to secure the right to these things and to facilitate the pursuit of its citizens’ happiness. To gauge the costs of our Covid response, we use as our primary measure the number of years that people lead happy lives, borrowing from the well-being-based WELLBY methodology recently developed at the London School of Economics, and now adopted within the UK government as a means of evaluating policies.

Finally, are there ways to repair the damage done during the Covid period to families and businesses, and/or to more intangible quantities such as individual liberty, institutional trust, and habits of thought? Should the ill-gotten gains accumulated by some individuals and groups during this period be recouped? If so, how, and what is the government’s role in supporting such a process of restitution?

Lessons for the future

With the benefit of hindsight, we can ask the following questions:

- Which professional perspectives were insufficiently developed, expressed, or integrated into the government response?

- What institutions structurally failed in their responsibilities, including by underperforming or by overstepping the borders of their designated authority?

- Which groups and sectors impeded the flow of emerging information about optimal public health responses, as well as the consequences of our responses?

- Did advisors to politicians and policymakers provide fearless advice to promote the public interest? Which people or groups impeded coordination across government institutions and analytical units?

- Would a different response have been feasible for key decision-makers at key points?

In each of these cases, we ask what alternative processes or institutional features could have delivered a more appropriate response, thereby pointing to reforms that might be considered in the future. In our search for institutional alternatives, we turn to examples provided by other countries with different institutional structures that had different initial responses. For example, we exploit the diversity of policy responses in other countries (such as Sweden) and in different states within the US, available due to the federalist system, to discover what alternative Covid responses could have been taken and what institutional differences may have produced them.

What changes to institutions are feasible in the American context that could have delivered a different response when faced with the circumstances of February and March 2020? Many federal and state institutions influenced the initial response, including in the media, academia, the medical bureaucracy (e.g., the CDC, the FDA, the NIH), and the governmental economics bureaucracy. The institutions of academia and the media that played a role could also be reformed.

Reforming individual institutions involves cross-cutting considerations that hold for all institutions, such as:

- The capture of institutions by special interests, including the medical authorities and the court system;

- Propaganda creation and dissemination, including the role of the government in guaranteeing free speech on private media platforms;

- Social contagion of emotional response, poor policy examples, and economic losses, including losses to developing countries due to disruptions to America’s normal role in the international economy;

- The ability to develop, express, and incorporate a diversity of views within state institutions, academia, the medical establishment, the media, and the professions;

- Self-interested coordination amongst powerful individuals and groups in government and business;

- Virtue signaling by institutions;

- The role of power concentration (e.g., in Big Tech and Big Pharma);

- The presence of relevant expertise within the responsible institutions, and their ability to speak out without fear of reprisal.

We also ask broader questions pertaining to both government and society. What social changes should government hinder or catalyze in broad areas such as how to craft and deliver a national apology to those who have been hurt during this period (e.g., the young), how most accurately to view this period, attitudes towards safety and the optimal limits of regulations, and how we view germs, death, and other people?

Beyond America’s borders, how could changes to international coordination mechanisms deliver better results for the US and the world in a future crisis?

Our questions lead to three different types of potential reactions to the policy decisions made during Covid times: (1) Justice: holding to account the decision-makers and systems that overstepped their authority or who willfully harmed the public; (2) Bureaucratic reform: looking for new regulations and institutions to address the failings found; and (3) Democratization: involving the general public more directly in the appointment of key decision-makers and in the coproduction of crucial public goods, like trusted information.

In these Articles of Inquiry, our primary aim is to set out the questions that should be asked in order to trace the lines of responsibility for policy-setting; gauge whether America’s responses were appropriate; estimate the damage of our responses; and scope the need and potential for institutional and social reform.

PART 1 The American Covid response: Lines of inquiry

What should have happened when Covid emerged? What actually happened? What were the roles and responsibilities of groups and individuals in crafting America’s response?

1(a) What should have happened?

America at the start of 2020 had a system of institutions and bureaucratic support that implicitly set out how a threat like Covid would be addressed. What should have happened, according to the implicit roles of these institutions and support systems, when Covid emerged?

1(a) i Institutional frameworks: Responsibilities of government

Which groups are tasked within the American bureaucracy with crafting policy evaluations/defenses? What protocols, including around “emergency declarations” or “states of emergency,” existed and could be used should a serious threat to public health emerge?

In terms of formal roles, many US institutions may take up the mantle of leadership during a pandemic, and what actually happens depends on what the President decides and which institutions opt to take on a leadership role. As Berman (2020) explains, state and federal responsibilities overlap:

As a public health matter, the primary responsibility for pandemic response lies with the states. At the same time, multiple laws, policies, and the numerous pandemic-response plans that the federal government has developed make plain that a successful fight against an outbreak of the scale and severity of COVID-19 requires a national response, with significant responsibilities necessarily falling on the federal government.

Various federal government entities … have developed emergency-response plans designed to guide pandemic response should the need arise. Some, such as the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Pandemic Influenza Plan, … updated most recently in 2017; the Homeland Security Council’s National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza and its Implementation Plan; the Defense Department’s Global Campaign Plan for Pandemic Influenza; and the National Security Council’s (NSC) infectious disease Playbook, are pandemic-specific. Others, like the National Blueprint for Biodefense, which is the product of a bipartisan commission made up of former lawmakers, executive-branch officials, and experts; the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) National Response Framework; and HHS’s National Health Security Strategy and Implementation Plan, cover a range of possible emergency scenarios that would include pandemics. Finally, there is a US Government Pandemic Crisis Action Plan (PanCAP) adapted specifically to respond to COVID-19.

Without exception, each of these plans envisions an energetic role for the federal government in meeting challenges such as the one we currently face. To fulfill this role, the government can employ two different sets of tools. The first are coercive—authorities empowering the federal government to require or prohibit particular actions, such as barring individuals suspected of carrying infectious diseases from entering the country. Just as important, however, are federal agencies’ numerous non-coercive tools—powers that enable federal actions to support preparedness and response efforts, such as coordinating among government entities, vaccine and treatment research, public education efforts, and management of resources.

One crucial responsibility that pandemic policies assign to the federal government is coordination… HHS is the designated leader for federal responses —though in the Covid-19 context that leadership role was transferred to the Vice President on February 28—headed up by a presidentially appointed Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR).

In addition to its coordinating function, the federal government’s role during an outbreak includes substantive responsibilities, such as engaging in epidemiologic studies to inform pandemic response efforts; developing necessary medical tools, such as vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics; determining the need for development or procurement of medical countermeasures; maintaining supply chains and stockpiling supplies; and monitoring demand for and distribution of those supplies by engaging with private sector partners and local governments. Supply chain management includes not only directing critical resources to where they are most needed, but also employing tools available uniquely to the federal government such as the Strategic National Stockpile.

States therefore have the primary responsibility, including general police power over public health, with federal agencies responsible mainly for informing and coordination. The Federal Department of Health and Human Services holds statutory authority to exercise interstate quarantine, but this authority has never been invoked in regard to humans. Many different agencies could try to take up responsibilities, and emergency powers can be invoked. However, the extent of these powers is legally contested, as demonstrated by the Health Freedom Defense Fund organization’s successful challenge of the travel mask mandates issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in which it was found that the CDC overstepped its statutory authority in issuing the mandates.

1(a) ii Institutional policies for the management of pandemics

What policies should have been expected, based on the consensus in US institutions before 2020 as to what should have been done?

Pandemics are some of the most widely studied topics in public health. The protocols for managing respiratory pandemics had been extensively researched and were widely understood and agreed upon within US government circles prior to 2020.

The US government’s pandemic plan

The 2017 US Department of Heath’s pandemic plan (Pandemic Influenza Plan 2017 UPDATE) contains no mention of lockdowns. It says:

NPIs [non-pharmaceutical interventions] that all people should practice at all times are particularly important during a pandemic. These everyday preventive actions include staying home when sick, covering coughs and sneezes, frequent and appropriate hand-washing, and routine cleaning of frequently touched surfaces. Community-level interventions can be added during pandemics and implemented in a graded fashion depending on the severity of the pandemic; these include measures aimed to reduce social contacts between people in schools, workplaces, and other community settings.

This extract is not about coercive lockdowns, but about voluntary measures.

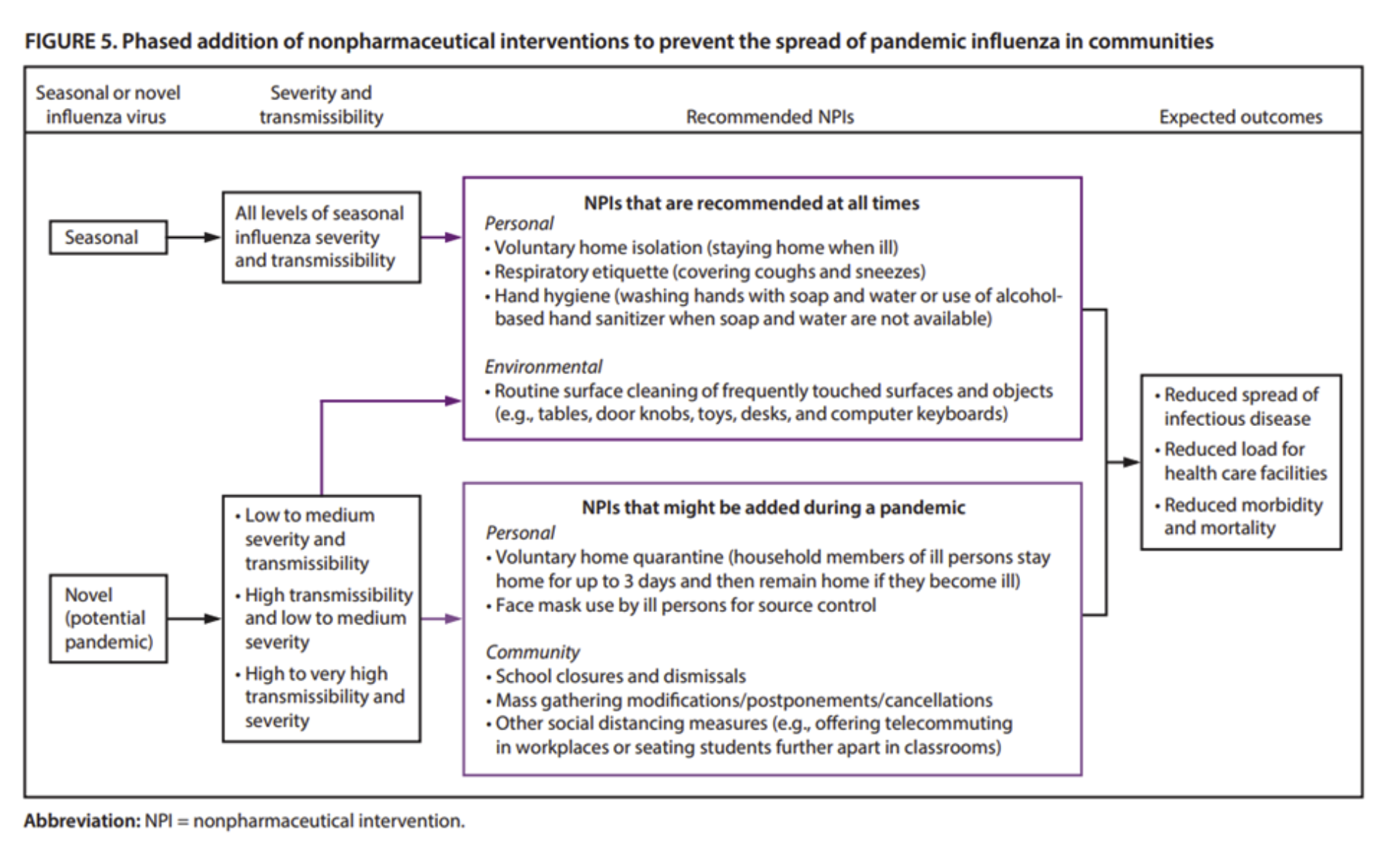

The CDC’s pandemic guidelinesThe following figure from the CDC’s Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza – United States, 2017 shows that like the US Department of Health, the CDC did not recommend society-wide lockdowns or curfews, even for worst-case pandemics.

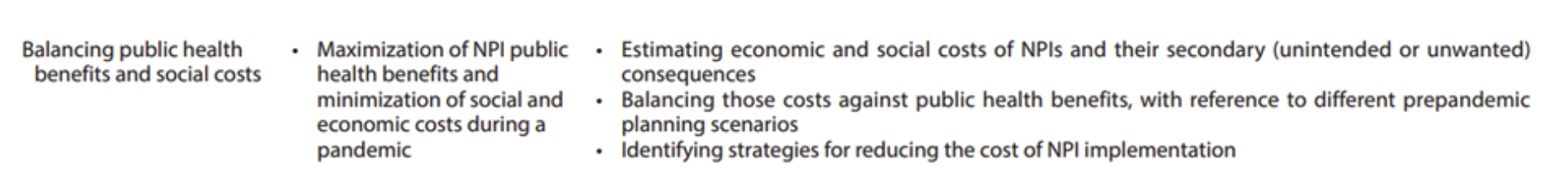

These 2017 CDC guidelines mention (on page 27) the need to avoid creating “intervention fatigue” and to make sure that the unintended costs of interventions are understood (“estimated”) and minimized (“minimization of social and economic costs during a pandemic”). The relevant section from a key table in the report is provided below. This illustrates that in 2017, the CDC itself explicitly recommended balancing the costs and benefits of any public health intervention.

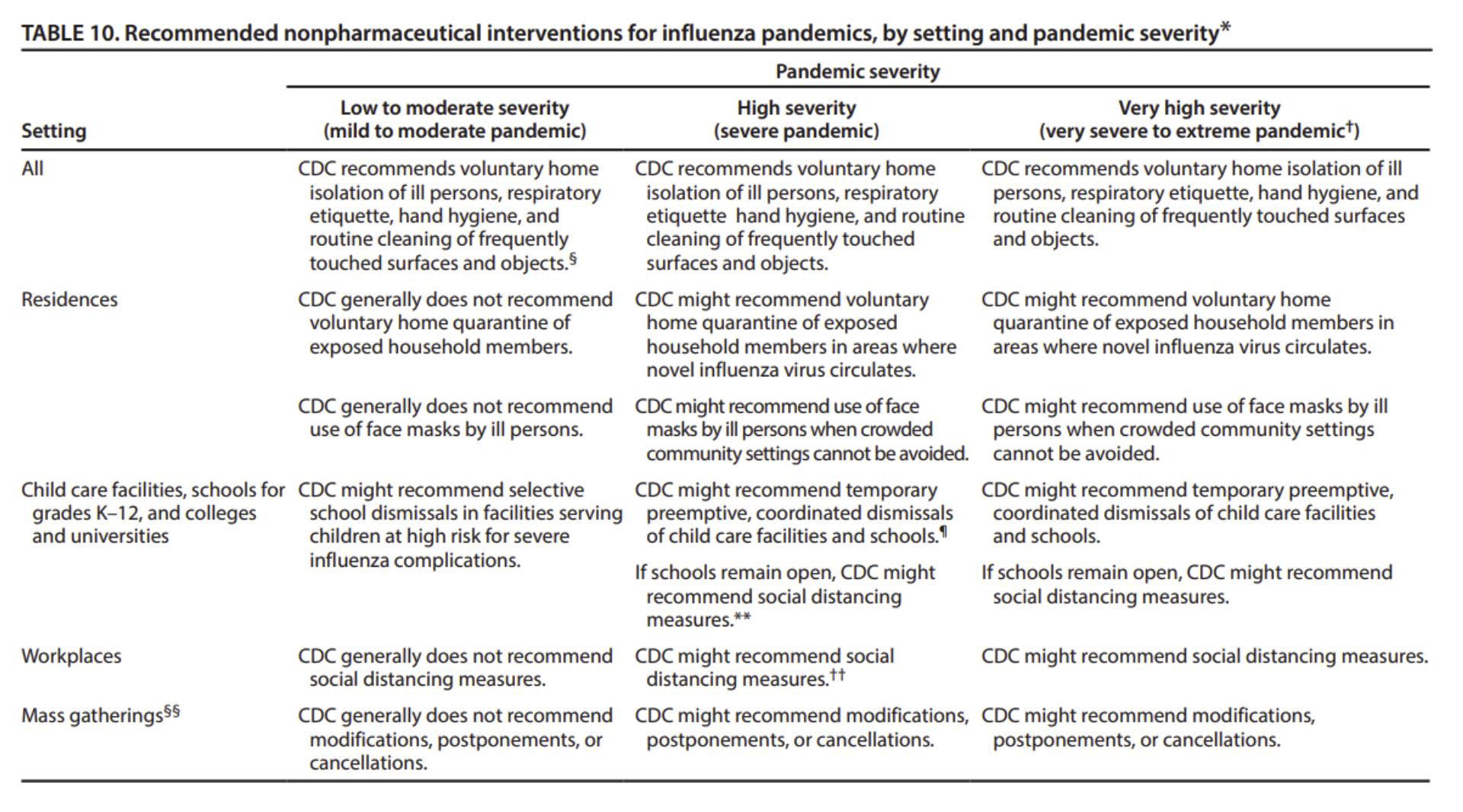

The following extract from a table on page 32 of the CDC’s 2017 guidelines is even clearer: even for a virus equivalent to the Spanish flu of a century ago, mandatory isolation of people would not be acceptable. For mild to moderate pandemics, the CDC “does not recommend voluntary home quarantine of exposed household members,” just as stated in the WHO’s 2019 guidelines. Covid would be categorized as a “moderate” pandemic with a vanishingly small impact on children, and hence one for which the only NPIs recommended by the CDC in 2017 were in relation to standard personal hygiene, including staying home if you are sick.

Moreover, the CDC’s guidance confined itself to recommendations. Mandates were not considered, even for extreme pandemics.

1(a) iii Summary of what should have happened according to pre-2020 structures and plans

In terms of what was supposed to happen when Covid emerged, the CDC should only have implemented lockdowns and other coercive measures after a cost-benefit analysis of these measures, while most policy should have been set at the state level rather than the federal level. The role of the CDC and other federal agencies should have been to inform, advise, and coordinate, rather than to coerce or mandate.

Berman’s 2020 paper explains that “under our federal constitutional system, the states enjoy inherent police power to regulate in the service of the public health, safety, and welfare of their people… The many pandemic-response plans developed at the national level recognize that the primary responsibility for addressing domestic health emergencies rests with states and localities… Even outside the emergency context, states regularly enforce mandatory screening and vaccination rules; conduct health inspections of places of business such as restaurants and nail salons; and engage in surveillance, tracing, treatment, and notification of individuals who have been exposed to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis or HIV. The routine exercise of these authorities fails to attract the attention devoted to pandemics like COVID-19, but they illustrate the nature of responsibilities carried out by local public health services across the country.”

Federal agencies did not follow either their own plans or the scientific consensus pre-2020, and neither was the division of roles between federal agencies and states as anticipated pre-2020. Key questions revolve around who took on more power than they should have, who let them do that, what the courts did, and whether in hindsight the decisions taken were illegal or even criminal. Challenges to the expansive use of federal power during the covid era have been successful when appealing to legislation describing the bounds of federal administrative authority, such as the Administrative Procedures Act (e.g., the Supreme Court’s ruling on the CDC’s second eviction moratorium, the district-court ruling against the above-mentioned travel mask mandate, and the finding by a circuit court against the covid vaccination mandate for federal contractors). Attempts to appeal to an overreach of the police power residing in states have been less successful in overturning state-level covid-era edicts, with courts often citing as precedent the 1905 smallpox vaccination case, Jacobson vs Massachusetts, in which state authority to compel vaccination was upheld over the principle of personal bodily autonomy. It bears mentioning that since 1905, the Supreme Court has found in other cases that individuals enjoy a personal right to refuse medical treatment, a finding that has yet to be reconciled with the Jacobson decision.

1(a) iv The management of prior pandemics

Historical examples provide an alternative perspective on the US government’s Covid response. Is what happened during Covid in line with what has happened during previous pandemics?

A 2015 paper by Rachel Kaplan Hoffmann and Keith Hoffmann outlines as follows the history of “cordons sanitaires” – attempts to isolate people from one another – as an infectious disease mitigation measure:

First developed during the Black Death of the Middle Ages, cordons sanitaires have since been used to quarantine inhabitants of Georgia, Texas, and Florida during the 1880s to combat the spread of yellow fever; Honolulu’s Chinatown during a bubonic plague outbreak in 1900; and Poland during a typhus outbreak after World War I; along with historical examples that include infected communities voluntarily cordoning themselves. These cordons achieved varying levels of medical success; at their worst, cordons sanitaires, including most American examples of the practice, have been examples of callousness and racism that unnecessarily victimized minority communities. However, an EVD [Ebola] outbreak in 1995 in Kikwit, Zaire was reportedly contained by “heartless but effective” cordons sanitaires.

These measures were effectively very short “lockdowns” applying to cities or small regions, but not to whole countries for extended periods of time.

While fear inevitably accompanied pandemics prior to the biological discovery of pathogens, fear-mongering became less common as the science of public health came of age in the middle of the 20th century. For example, during the Asian flu in 1957, “Public health experts did in fact consider school closures, business closures, and a ban of public events but the entire ethos of the profession rejected them. There were two grounds for this rejection: lockdowns would be too disruptive, disabling the capacity of medical professionals to deal competently with the crisis, and also because such policies would be futile because the virus was already here and spreading.”

A golden age for public health and epidemiology arrived during the 1950s and 1960s, when experts like Donald Henderson were finally mastering the nature of pandemics. Donald Henderson is celebrated as the person who oversaw the eradication of smallpox from the planet.

Henderson’s view was that it is impossible to stop most viruses through border control.1 Henderson contended that the spread of most viruses cannot be stopped unless the first case (the “index case”) in a country is stopped, and the next case is stopped, and every additional index case is stopped as it erupts. He noted that some viruses can indeed be controlled through quarantines of the sick, and successful attempts have been made to do so, such as for Ebola. Yet for most viruses, including influenza, he argued that if even a single person slips through the net of control, then the battle is lost. It is far more sensible in such cases, Henderson argued, not to implement hard border controls but rather to manage the disease in order to minimize harm. In his words: “this idea that in this day and age one is going to intercept people coming across the border and you’re going to stop the spread of the disease is a concept that was antiquated a very long time ago.”

1 See Donald Henderson’s comments on this topic at the link from timestamp 32:35, speaking on a panel at the 5 March 2010 conference on “The 2009 H1N1 experience: policy implications for future infectious disease emergencies” at (Role of Disease Containment in Control of Epidemics (Panel)).

In relation to social distancing interventions generally, in 2007 it was reported in the National Library of Medicine that “Donald Henderson of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center cautioned against relying on models that do not take into consideration the adverse effects or practical constraints that such public health interventions would entail. Accepting such models uncritically, he warned, could result in policies that ‘take a perfectly manageable epidemic and turn it into a national disaster.’”

Evidently, extended lockdowns of whole populations had not been used in the modern era and were regarded as unwise by eminent epidemiological experts. They were known to cause significant negative effects on many other dimensions of society, including our ability to continue to control the target disease.2

2See this discussion of Donald Henderson’s position and the history of the use of lockdowns provided by Jay Bhattacharya, and this reprint of a paper by Henderson.

Henderson’s view became the scientific consensus. Core players in the American Covid response, such as Anthony Fauci, initially followed Henderson’s view of the pointlessness of lockdowns prior to the Covid pandemic. In 2014, Fauci did not advocate quarantines even for Ebola health workers. As late as 24 January 2020, Fauci expressed opposition to lockdowns, saying “historically when you shut things down it doesn’t have a major effect.”

Further, counterintuitive though it may seem, there are arguably great public health benefits from human intermingling. Some of these may derive directly from our interaction with pathogens, including when we travel internationally. Since at least her “Princeton in Europe” lecture of 2013, Dr Sunetra Gupta of Oxford University has argued that global immunity to viruses is strengthened from international travel:

Virulent pathogens cannot be the only things we bring back from countries where they’ve originated. It is more likely that we’re constantly importing less virulent forms which go undetected because they’re asymptomatic and these may well have the effect of attenuating the severity of infection with their more virulent cousins.

After all, the oldest trick up our sleeves is, as vaccination goes, is to use a milder species to protect against a more virulent species. Perhaps this is something we’re inadvertently achieving by mixing more widely with a variety of international pathogens.

According to Dr Gupta, the same principle applies to children, who “benefit from being exposed to this [Covid] and other seasonal coronaviruses.” The logic is that getting a less harmful infection protects children against more serious infections in the future. Therefore, Dr Gupta contends, “the best way to [safeguard against pandemics] is to build up a global wall of immunity. And it may be that we’re unwittingly achieving this through our current patterns of international travel.” As part of our response to Covid, we have paused this potential mechanism of building group-level immunity to pathogens.

While communities have been temporarily isolated during severe pandemics of the past, top scientists had come to the conclusion by the middle of the 20th century that extended lockdowns would not work once a virus became a pandemic, and that it is actually detrimental to the overall health of human societies to attempt to avoid viral spread.

Yet, fear and business opportunities have combined to produce a less sanguine response by governments to the pandemics of the past 50 years.

A paper published in the WHO Bulletin in 2011 described as follows how fear overpowered a calm public health response in Europe to bird flu and swine flu:

The repeated pandemic health scares caused by an avian H5N1 [2006] and a new A(H1N1) [2009] human influenza virus are part of the culture of fear. Worst-case thinking replaced balanced risk assessment. Worst-case thinking is motivated by the belief that the danger we face is so overwhelmingly catastrophic that we must act immediately. Rather than wait for information, we need a pre-emptive strike. But if resources buy lives, wasting resources wastes lives. The precautionary stocking of largely useless antivirals and the irrational vaccination policies against an unusually benign H1N1 virus wasted many billions of euros and eroded the trust of the public in health officials. The pandemic policy was never informed by evidence, but by fear of worst-case scenarios.

The tendency of public health practitioners to grossly exaggerate risks and foster tunnel-visioned panics that ignore other health issues is well-known. The behavior of public health practitioners in relation to swine flu was questionable, as reported in many documents and by the Council of Europe, the continent’s leading human rights organization.

Lockdowns were used again in 2014 to try to control Ebola in Africa. It was noted in the New York Times article that reported this that lockdowns created significant logistical and other challenges and impacted human rights. The Hoffman and Hoffman paper above evaluated these 2014 Ebola lockdowns (“cordons sanitaires”) according to four fundamental ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Apart from the logistical issues and mismanagement they note, their main conclusions are noteworthy:

[T]hese cordons have had variable effectiveness. Clinically, very small-scale cordons—quarantining individual patients and those with whom EVD patients have come into direct contact—have demonstrated effectiveness, while medium- and large-scale cordons around neighborhoods, regions, and nations have proven ethically troubling, largely ineffective, and difficult to enforce.

[P]ublic health officials should focus on the containment of EVD by zeroing in on those already infected and containing its spread through small-scale cordons sanitaires—like those that have been successful in Nigeria and Senegal—conducted in the most ethical manner possible. Fortunately this type of effort has demonstrated effectiveness; in their most recent report, the WHO states that on a national level, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone have achieved the capacity to isolate and treat all reported EVD cases and to bury all EVD-related deaths safely and with dignity.

Even while strictly enforcing small-scale cordons, public health officials should be vigilant to prevent unnecessarily harsh or capricious cordons as inappropriate quarantines raise ethical issues, may create public health panic, and waste resources.

When they reflected on the many pandemics between 1940 and 2006, Torsten Engelbrecht and Claus Kohnlein in their 2007 book describe the risks to humanity when public health authority is misused.

We are not witnessing viral epidemics; we are witnessing epidemics of fear. And both the media and the pharmaceutical industry carry most of the responsibility for amplifying fears, fears that happen, incidentally, to always ignite fantastically profitable business. Research hypotheses covering these areas of virus research are practically never scientifically verified with appropriate controls. Instead, they are established by “consensus.” This is then rapidly reshaped into a dogma, efficiently perpetuated in a quasi-religious manner by the media, including ensuring that research funding is restricted to projects supporting the dogma, excluding research into alternative hypotheses. An important tool to keep dissenting voices out of the debate is censorship at various levels ranging from the popular media to scientific publications.

In summary, it was well understood that applying community-wide lockdowns even for a virus like Ebola is fraught. Even for Ebola, only “small-scale cordons” had been evaluated as being effective. When large-scale lockdowns even for a lethal virus like Ebola were seen as unscientific and unethical, applying these measures to try to stop a flu-like virus was simply not considered.

Yet while the scientific consensus and WHO recommendations in early 2020 made clear the folly of lockdowns and other highly coercive measures, there was also a known risk that fear and business opportunities would combine to push for a costly overreaction.

1(b) What actually happened?

What sequence of decisions constituted the setting of the American Covid policy response? Thousands of decisions made at the state and federal level fed into the response. We briefly list below the federal decisions that carried the largest economic costs.

1(b) i A brief timeline of events and major decisions taken during the Covid era

In late November 2019, an unknown virus was detected in Wuhan, China that is now known as SARS-CoV-2. On January 20, 2020, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced that “the NIH is in the process of taking the first steps towards the development of a vaccine.” The next day, on January 21, 2020, the first Covid case was confirmed in the United States.

On January 23, 2020, WHO stated that Covid did not yet constitute a public health emergency of international concern. Despite this, a task force was formed by the White House to provide accurate and current health and travel information on January 29, 2020.

On January 30, 2020, WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and the next day, on January 31, 2020, the Trump administration announced that foreign nationals who had traveled to China in the last 14 days would be denied entry into the United States.

On February 10, 2020, WHO experts arrived in China to assist with containing the Coronavirus outbreak. On February 11, 2020, the Coronavirus was named Covid-19.

The Federal Reserve lowered interest rates by half a percentage point on March 3, 2020. This was the first unscheduled rate cut since 2008.

On March 10, 2020, Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow announced a transition to fully-online classes by Monday, March 23 upon students’ return from Spring Break. Students would continue studying remotely “until further notice.” Harvard’s announcement followed the closing on March 7, 2020 of the University of Washington, the first large university in the US to close due to Covid.

On March 11, 2020, WHO declared the Coronavirus outbreak a pandemic and President Trump announced that he was restricting travel from Europe to the United States for 30 days to slow the spread of Covid. American citizens and permanent residents were exempt from the ban and would be screened prior to entering the United States.

On March 13, 2020, a national emergency was declared by President Trump and on March 18, 2020, a Coronavirus relief package was signed into law. On March 27, 2020, a $2 trillion stimulus package was signed into law by President Trump.

Between late March 2020 and May 2020, authorities in the individual states made decisions on forced business closures, the distinction between essential and nonessential jobs, and rules on subsidies for those forced to close down.

On April 2, 2020, the Department of Labor announced that 6.6 million US workers filed for their first week of unemployment benefits in the week ending March 28. This was the highest number of initial claims of unemployment in history. In response, President Trump signed off on a $484 billion small-business stimulus bill, the majority of which funded the Paycheck Protection Program on April 23, 2020.

On April 3, 2020, the Trump administration recommended Americans begin wearing “non-medical cloth” face coverings.

Scott Atlas’ 2021 book, A Plague Upon Our House, provides a summary of what happened at the federal level from the point in late 2020 when he joined the Trump White House’s Coronavirus Task Force and identified that the federal Covid response was being led by Anthony Fauci (Director of NIAID and Chief Medical Advisor to the President since 2021) and Deborah Birx (White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator since February 2020). Both Fauci and Birx supported extreme responses to Covid that were inconsistent with America’s pre-2020 pandemic management plans. Coercive powers were increasingly vested in the CDC, something increasingly seen as controversial in legal and journalistic circles in 2022. Yet, it was President Trump who declared a National Emergency on March 13th, 2020, and also he who began issuing stay-at-home orders from March 17th, 2020. Trump also approved the application of power by Birx, essentially letting the CDC and others drive policies while remaining formally responsible, as President.

The decision to lock down and treat the virus as an emergency in 2020 was widely shared. As Berman (2020) noted, “All fifty states have declared COVID-19 a public health emergency, a step that can augment the powers of governors or local officials, often authorizing them to impose such measures by fiat … [T]he courts—including the Supreme Court—have extended state officials significant leeway in determining what is required to address public-health risks.”

On December 11, 2020, an emergency authorization was granted by the FDA for the Pfizer/ BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine. This was followed by an emergency authorization for the Moderna vaccine on December 18, 2020 and for Johnson & Johnson on February 27, 2021.

On December 27, 2020, Trump signed a second stimulus package bill of $2.3 trillion.

On December 28, 2020, Trump signed a US $868 billion coronavirus relief and government funding bill as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021.

On January 29, 2021, the CDC ordered the use of masks on public transportation conveyances and at transportation hubs.

On March 11, 2021, President Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan, which provided another round of Coronavirus relief with an estimated cost of $1.844 trillion (about 8.8 percent of 2020 GDP). The plan focused on investments in the public health response and providing time-bound assistance to families, communities and businesses. It extended the unemployment benefits programs (including supplemental unemployment benefits), sent direct stimulus payments of $1,400 to eligible individuals, provided direct aid to state and local government, added resources to the vaccination program, and increased funding for school reopening.

On August 12, 2021, the FDA authorized an additional vaccine dose for immunocompromised people. On September 24, 2021, CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky recommended boosters to people aged 18 to 64 who are at increased risk of Covid in addition to those with underlying health conditions. On November 19, 2021, the FDA authorized boosters of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccine for all adults. On November 29, 2021, the CDC recommended that anyone over 18 years old receive a booster six months after their second vaccine. On December 16, 2021, the CDC stated that the Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna vaccines were preferred over the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

On September 9, 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order mandating SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations for employees of federal contractors and subcontractors. This led to mass layoffs and vaccinations to prevent loss of livelihoods.

On December 22, 2021, the FDA authorized Paxlovid, Pfizer’s antiviral pill for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2. On December 23, 2021, the FDA authorized molnupiravir, Merck’s antiviral pill. Antiviral pills are authorized by the FDA to be taken by sick people at home before they are sick enough to be hospitalized.

On December 27, 2021, the CDC shortened the recommended period for the isolation of people who tested positive for Covid from 10 days to five days if no symptoms are present, and five days for vaccinated people who test positive.

On March 29, 2022, a second booster of Pfizer/ BioNTech and Moderna was approved by the FDA for adults 50 and older. On the same day, the CDC endorsed a second booster for adults 50 and older.

On April 18, 2022, the Transportation Security Administration declared that it would no longer be enforcing mask mandates on airplanes.

1(b) ii Initial assessment of the American Covid policy response

The US federal government’s Covid response was not consistent with its own pre-2020 pandemic management plans, and defenders of the policies made no reference to these plans, instead more frequently mentioning other countries’ Covid responses.3

3For example, on 30 April 2020 Trump tweeted “Sweden is paying heavily for its decision not to lockdown.”

In his 2021 book, Atlas refers to the disconnect between what Fauci and Birx were saying and the impression he had from his first meeting with President Trump: “I also sensed, even in this initial conversation, that he [Trump] was frustrated — not just at how the country was still shut down, but that he had allowed it to happen, against his own intuition.” Whilst this may or may not be true, what matters is actual decisions taken, not private misgivings, and the buck stops with the President.

To inquire further about how the US response to Covid came to deviate so much from what it should have looked like, one could ask questions such as the following:

Who appointed the White House Coronavirus Response Team? Who at the CDC decided not to adhere to or give voice to the CDC’s own pre-2020 pandemic management plans? Was the failure of key decision-makers to apply the proportionality principle that is central to oaths (such as the Hippocratic Oath, often summarized as “First, do no harm”) and rules of thumb in medicine (e.g., cures should not be worse than the disease) criminal?

1(b) iii The legal context

What did the courts initially decide about the coercive Covid policy measures?

US courts struggled to deal with the intrusive policies adopted in the name of fighting Covid. On 14 September 2020, the judgment in the case of “United States District Court for the Western District Of Pennsylvania, Civil Action No. 2:20-cv-677” (County of Butler v. Wolf) declared lockdowns unconstitutional. However, other courts across the country interpreted things differently, and so lockdowns and other mandates continued in the US long after this judgment.

A case can be made that in the future, there should be a quicker way for courts to hand down judgments on policies as widespread and coercive as those implemented in the Covid period.

1(b) iv Changes to health care and socio-economic life: Lines of inquiry

Many changes to American society were justified as necessary responses to Covid. Important lines of inquiry relate to the major decisions taken – e.g.,:

- Within the machinery of government, who told hospital administrators to close to non-Covid patients? Was that decision legal and made on the basis of evidence that included a clear consideration of costs?

- Who decided on the division into “essential” versus “nonessential” workers, and “elective” versus “non-elective” surgeries?

- Who decided on the system of subsidies to hospitals for Covid diagnoses?

- Who decided on the rules to be enforced in the aged-care sector?

- Who decided on the policies relating to quarantines, masking, social distancing, and restrictions on personal freedoms?

1(c) The voice of groups outside government

Many professional groups, including public health professionals, epidemiologists, and economists, composed open letters and petitions that influenced decision-makers during this time. Politicians were vulnerable to this influence partly because of their need to be seen to be doing something about what was perceived as a serious threat.

Were economists in particular asked to contribute to Covid policy-setting, and when they were, what did they say? If they were not asked, why weren’t they, given the large amount of economic fallout that would be inevitable from the Covid policy response, as explicitly acknowledged in pre-2020 pandemic management plans?

1(c) i US and European economists

According to Scott Atlas, no top economics officials in the US government were asked to weigh in on Covid policy. In no press conferences were the economic costs of lockdowns considered.

Outside of government, did economists make their views known? Mikko Packalen and Jay Bhattacharya pointed out on 29 August 2021 that:

Economists, who study and write about these phenomena for a living, had a special responsibility to raise the alarm. And though some did speak, most either stayed silent or actively promoted lockdown. Economists had one job—notice costs. On COVID, the profession failed.

In support of this contention, on 7 April 2020 the Financial Times reported that:

The IGM Economic Experts Panel’s latest survey of top US macroeconomists asked for their view of the statement “Abandoning severe lockdowns at a time when the likelihood of a resurgence in infections remains high will lead to greater total economic damage than sustaining the lockdowns to eliminate the resurgence risk”. Eighty per cent of the panel agreed, the rest were uncertain or did not respond. Not a single expert disagreed.

In Europe, 65 per cent of respondents agreed that “severe lockdowns — including closing non-essential businesses and strict limitations on people’s movement — are likely to be better for the economy in the medium term than less aggressive measures”. Only 4 per cent disagreed.

Rachel Griffith, president of the UK’s Royal Economic Society and professor of economics at the University of Manchester, was reported to have the following view:

“Clearly there is a cost” to the lockdowns, said Ms Griffith, “but what is the counterfactual? The cost of not containing the virus would be greater — even economically.” Not only was saving lives inherently valuable, but fear of contagion would cause economic disruption even in the absence of government action, she explained.

In their minds, such economists appear to have come to the view that society would be disrupted even without lockdown mandates – whether due to widespread fear of contagion leading to “self-lockdown,” suffering due to witnessing friends and family dying of Covid, or even due to prime-age workers dying of Covid and thereby decimating the economy – such that the marginal cost of forcing everyone to stay at home would be small. No value was placed in this reasoning upon individual liberty and agency. Moreover, such beliefs were not openly cognizant of the pre-2020 scientific consensus, based on the deep understanding of pandemics reached by Henderson and others, nor put to the empirical test of comparing what happened in similar regions that adopted different policies.

Gigi Foster and Paul Frijters note in relation to the IGM Economic Experts Panel survey question that “this is a leading question, as its wording alone invites the responder to agree, and assumes a connection between lockdowns and viral trajectory. Still, PhD-qualified economists working for world-class universities would presumably have the skills needed to resist implicit pressure towards having a particular opinion on a survey question directly related to their expertise. However, not a single American economist in the group went on record as disagreeing with the statement above. Only 14% of the 44 respondents responded “Uncertain,” and 7% abstained.” 4

4 These authors note that those who selected “Uncertain” were David Autor, Linan Einav, Pinelopi Goldberg, Jonathan Levin, Jose Scheinkman, and James Stock. Those who abstained were Abhijit Banerjee, Amy Finkelstein, and Caroline Hoxby.

The following selected analyses by US academic economists were published in 2020 and 2021 in favor of lockdowns:

- A May 2020 paper by Barrot et al said that “state-mandated business closures might have cost $700 billion and saved 36,000 lives so far.”

- A 14 May 2020 paper by Courtemanche et al. argued in relation to social distancing policies that “there would have been ten times greater spread of COVID-19 by April 27 without shelter-in-place orders (ten million cases) and more than thirty-five times greater spread without any of the four measures (thirty-five million cases).”

- A 12 October 2020 piece in JAMA by Cutler et al. looked at the costs of the Covid pandemic, but failed to distinguish the costs of Covid itself from the costs of responses to it, like lockdowns. It found “estimated cumulative financial costs of the COVID-19 pandemic related to the lost output and health reduction … at more than $16 trillion, or approximately 90% of the annual gross domestic product of the US.”

- In a 14 January 2021 paper, economist Anna Scherbina argued that “[t]he failed Swedish experiment has illustrated that it may be impossible to selectively protect the vulnerable population without a government intervention.” She modeled the viral trajectory of Covid using the “SIR” (susceptible, infected, recovered) model frequently used in epidemiology, and again mixes together the costs of the virus itself with the costs of a response to it. In her words, “The expected future monetary cost of the COVID pandemic is calculated from the following three components: (1) the loss of productivity due to missed work of the symptomatically ill; (2) the cost of medical interventions that could have been used elsewhere; and (3) the value of lives of the projected fatalities. The benefit of a lockdown is calculated based on reducing the number of new infections going forward, and therefore avoiding a portion of these costs.” This method ignores all other negative well-being effects of lockdowns. She then estimates “that if the United States imposed a nation-wide lockdown similar to the lockdowns in Europe, which, depending on the assumptions, would optimally last between two and four weeks, it will generate a net benefit of up to $1.2 trillion, or 6% of GDP.”

These papers fail to count the main costs of lockdowns and other coercive policy measures, and do not recognise the possibility of pursuing a targeted policy response instead of excessive interventions. These failures may be partly explained by the fact that most academic economists are not well-versed in cost-benefit analyses, which is instead largely the purview of government economists and specialist consulting economists.

On the other hand, a few economists did try to grapple early on with the full effects of lockdowns. One of the first was John Birge of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business who, with Scott Atlas, Ralph L. Keeney and Alexander Lipton, published a piece on 25 May 2020 arguing that “The COVID-19 Shutdown Will Cost Americans Millions of Years of Life.”

On 24 August 2020 the Wall Street Journal reported that “some experts are urging policy-makers to pursue these more targeted restrictions and interventions rather than another crippling round of lockdowns. ‘We’re on the cusp of an economic catastrophe,’ said James Stock, a Harvard University economist who, with Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina and others, is modeling how to avoid a surge in deaths without a deeply damaging lockdown. ‘We can avoid the worst of that catastrophe by being disciplined,’ Mr. Stock said.”

More economists have spoken out since then against lockdowns. In a paper published in January 2022, three economists (one Swedish, one Danish, and one from Johns Hopkins University) concluded on the basis of a review of 100 papers that lockdowns in Europe and the US reduced Covid mortality by 0.2% on average. This report led to a furor in the media, including an article claiming that “Economists Are Fueling the War Against Public Health.”

1(c) ii Economists outside the US and Europe

On 19 April 2020, 256 academic and non-academic economists from Australia, the USA, Canada, the UK, and Japan released an open letter in support of lockdowns. They argued:

We cannot have a functioning economy unless we first comprehensively address the public health crisis. The measures put in place in Australia, at the border and within the states and territories, have reduced the number of new infections. This has put Australia in an enviable position compared to other countries, and we must not squander that success.

We recognise that the measures taken to date have come at a cost to economic activity and jobs, but believe these are far outweighed by the lives saved and the avoided economic damage due to an unmitigated contagion. We believe that strong fiscal measures are a much better way to offset these economic costs than prematurely loosening restrictions.

As has been foreshadowed in your public remarks, our borders will need to remain under tight control for an extended period. It is vital to keep social-distancing measures in place until the number of infections is very low, our testing capacity is expanded well beyond its already comparatively high level, and widespread contact tracing is available.

A second-wave outbreak would be extremely damaging to the economy, in addition to involving tragic and unnecessary loss of life.

This letter suggests that these economists failed to recognise the costs of lockdowns beyond narrow economic harms. They ignored the enormous losses in well-being that were becoming evident even at that early stage of lockdowns and border closures. Further, in their thinking, economic harms stood in a separate category from harms to human life and well-being, which are more fully explored in Part 2. They therefore displayed some common misconceptions of those untrained in cost-benefit economics.

As in the US and Europe, despite the majority view of economists in other countries being in support of strong restrictions, a few voices disagreed. On 8 June 2020, some Australian economists and other academics and laymen signed an open letter to the National Cabinet of Australia, demanding a cost-benefit analysis. This matter is discussed in detail in a May 2022 paper by Gigi Foster and Paul Frijters. The paper focuses on “the weak resistance mounted by the Australian economics profession during this period, and the role played by many Australian economists as apologists for Australia’s most catastrophic peacetime economic policy failure.” Their analysis concludes that most Australian academic economists not just forgot the most basic principles of their discipline, but abetted what they considered to be crimes by governments. Their recommended solution: “For the Australian economics profession and society as a whole, we think truth commissions are a reasonable way forward to recognise that crimes during this period have been aided and abetted by our profession, to acknowledge the domestic and international victims of those crimes, and to establish a more truthful basis from which to move on.”

1(c) iii The role of “little enforcers” on (social) media and in communities

In previous pandemics, writers in the media seemed aware of their impact on society and acted responsibly in reporting deaths. It was noted in The Lancet on 25 May 2020 that:

At the end of July, 1957, the Daily Mail issued a dire warning about a “new outbreak of Asian flu” when a 1-year-old girl fell ill in Fulham. The Guardian surrendered its cool editorial tone for a headline reading: “Crash Fight Against Asian ‘Flu’”.

However, such headlines were the exception and for the most part newspapers seem to have behaved responsibly during the pandemic. Publishers were also reluctant to be seen to be stoking public fears.

Yet in Covid times, the media behaved differently, exacerbating the hysteria and blocking attempts to calm people down.

Bullying was rife not only on social media and in traditional media, but in offices and in the public space. Shops discriminated against the unvaccinated, friends bullied other friends in order to enforce compliance, and school administrators made life hard for unmasked and unvaccinated children. This was a direct repeat from what was normal in Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe before 1990, where neighbor informed on neighbor.

Writers on various media platforms leveled accusations at dissenting voices, with Brownstone Institute for example being labeled as part of disinformation campaigns and as being sponsored by “dark money,” the Koch Foundation, and “climate science deniers.” Individual dissenters were pilloried, including on social media. A cottage industry emerged early on of “fact checks,” being funded either by universities or by the mainstream media, to denigrate the opinions of those who held what were portrayed as “standard, risk-based” views on the topic. Much of this constituted private-sector restriction on free speech, leading to the question explored in Part 3 of this document of how to ensure free speech when public media space is privately owned.

In academia, bodies like the NIH were involved in undermining the expression of dissident views. An email trail shows how Fauci and his colleagues undermined the work of the Great Barrington Declaration. Scott Atlas was pilloried by the media and also by the academy. In Australia, people within government departments who had alternative views were stifled (as detailed in Sanjeev Sabhlok’s 2020 book), leading some to resign.

The government became an enforcer of “right speech” in other ways during Covid times, often by using its power to threaten media companies that did not comply. With the incoming Biden administration, the government started demanding that social media companies block free speech:

In May 2021, the White House began a coordinated and escalating public campaign to stop the flow of purported “health misinformation” related to Covid-19. In a May 5, 2021 press briefing, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki stated that the President believed social media platforms have a responsibility to censor health “misinformation” related to Covid-19 vaccinations, that by not doing so they were responsible for American deaths, and that the President believed “anti-trust” programs were in order to effectuate this end. In other words, if tech companies refused to censor, they would face antitrust investigations—or worse. By July, the Surgeon General and HHS ratcheted up the pressure by issuing an advisory on the subject, commanding technology platforms to collect data on the “spread and impact of misinformation” and “prioritize early detection of misinformation ‘super-spreaders’ and repeat offenders” by “impos[ing] clear consequences for accounts that repeatedly violate platform policies.”

Government directives that attack free speech directly insult the First Amendment, as recognised by the instigation of legal challenges to them.

A more detailed review of what happened in the media during the Covid era is provided in the Media line of inquiry released by Brownstone Institute.

PART 2 The impact of the policies undertaken: Lines of inquiry.

The US was the first country in the world to formally adopt a cost-benefit framework for public policy in 1981 during the Reagan administration, and there is a strong culture of conducting CBA or cost-effectiveness analyses to evaluate health policy. Still, no government-led CBA was issued anywhere in the US that evaluated the validity of the Covid policies being implemented, and health economists outside government in general did not step forward with their views.

Compared to the outcomes in 2019, the US and the world as a whole are poorer, unhealthier, less skilled, less employed, and less free. To assign any of this decline to a policy with confidence, we need a unit of account in which to quantify and sum the diverse effects of the policy together into a single measure of ‘what matters,’ and we need a reasonable method of identifying the part of the damage due to the policy rather than to the new virus itself, or the weather, or any other factor outside human control. We take these issues in turn.

2(a) What matters?

We take seriously the Declaration of Independence that talks of citizens’ inalienable rights to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Accordingly, all changes to the number of happy years of life lived by the population should be counted and recognized. The number of years lived is used rather than the number of lives, recognizing the standard argument that everyone eventually dies, so no policy can aim to prevent death but only to postpone it. Yet not only the number but also the quality of years lived matters. To measure the quality of years lived, we draw from a huge literature that has looked at the determinants of life satisfaction, in practice measured by asking individuals the following question (or a close variant): “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?”

A person’s response to this question, answered on a scale of 0 (completely unsatisfied) to 10 (totally satisfied), is interpreted as her vote about how much her circumstances have made her satisfied with her life. A 1-point change in this 0-10 scale for one person for one year is termed a WELLBY, and is the basic unit of account that can capture changes in human well-being in different realms.

The literature on life satisfaction has found effects on human well-being from changes to people’s circumstances in different realms. For example, we know that, roughly speaking, getting married has an effect of around one WELLBY: around the time of marriage people are happier, a savoring effect that starts to occur about a year before marriage and fades about a year after the marriage happens. Since a very healthy person experiences around 6 WELLBYs in a year, this means we know that getting married is ‘worth’ around the same amount of human well-being as two months of life: people would be willing to live two months fewer in exchange for getting married. Conversely, if a policy prevents one million marriages, then the WELLBY cost of that is around 167,000 life years. If the average Covid victim has been estimated to have had around 3 to 5 good years of life left, as Foster and Sabhlok (2022) suggest, then preventing a million marriages would be equivalent to suffering 35,000-50,000 Covid deaths. In a similar fashion can one translate the costs of mental health problems, childhood disruptions, additional health problems, and future government service reductions into lost WELLBYs, and thereby into fewer ‘happy years of life.’

The WELLBY methodology was developed at the London School of Economics between 2017 and 2020 and has been adopted by the UK government as a means to evaluate complex policies. 5 It was first published in Frijters et al. (2020) and has been adopted by the UK Treasury (2021) for policy evaluations and appraisal throughout UK institutions. New Zealand has recently followed suit. The WELLBY is also being advocated for use by other countries by the World Happiness Report (e.g., Helliwell et al. 2021).

5 The first published WELLBY paper is Frijters et al 2020. The Handbook that explains and applies the methodology is Frijters, P., & Krekel, C. (2021). The adoption of the basic tenets of this methodology by the UK government was explained and formalized in the Green Book used throughout England and Wales.

While comprehensive economic evaluations of specific NPIs such as masking, curfews, and vaccine mandates have not as yet been conducted, the WELLBY methodology has now been applied to evaluate Covid lockdowns in the UK (De Neve et al. 2020), Ireland (Ryan 2021), New Zealand (Lally 2021), Canada (Joffe 2021), Australia (Foster 2020c; Foster and Sabhlok 2022), the world, and various countries in continental Europe (Frijters and Krekel 2021, Frijters 2020b). All of these inquiries lead to the conclusion that the costs of Covid lockdowns outweighed their benefits by at least 3 to 1, even if lockdowns would last only a month. Using best-guess instead of optimistic-about-lockdowns assumptions, the usual conclusion is that lockdowns had costs 50 times higher than benefits. Similar conclusions have been reached via the older QALY methodology under which quality of life is not measured via life satisfaction but instead via health-related questions or via standard economic value-of-life measures. A recent review of 100 cost-benefit studies based on empirically identified outcomes, as opposed to model simulations, arrived at a similar conclusion. For instance, Miles et al. (2020) found a 50:1 ratio of costs to benefits of lockdowns in the UK, looking only at physical health.

2(b) The counterfactual

A crucial question in any policy evaluation is what the outcome would have been under policies different than the one actually implemented. History cannot be run with different policies, which would be the ideal, so in practice researchers settle for comparing the outcomes in regions that were very similar before 2020 but adopted very different Covid policies, trying to take account as best they can the divergent characteristics of different regions. 6

6 The 2022 World Happiness Report documented a fairly dramatic fall in happiness levels around the world, with stronger drops in regions with longer and more severe lockdowns.

When comparing outcomes between regions with different Covid policy settings, what is being evaluated is the totality of thousands of small individual policies, ranging from social isolation rules for young children to mandated business closures. The effect of the policy collection in a particular region estimated in this fashion is often labeled as the effect of ‘lockdowns’ or of ‘zero-Covid policies’. While it is not feasible to provide exact evaluations for every small policy, rules of thumb can be derived from the estimated effects of the totality of more or less restrictive policies to identify the main sources of costs, and therefore the main effects of different policies.

In the WELLBY cost-benefit analyses in other countries, researchers have compared outcomes in their country with those of Sweden, or to a ‘no changes from 2019 trends’ scenario. Using the first counterfactual effectively means that researchers assume that their country would have seen the same change in outcomes in various realms as Sweden experienced, had they adopted Swedish policies. For example, the assumption would be that if the UK had taken up Swedish policies, it would have seen no change in mental health and only a 6%-of-GDP increase in government debt (which were the Swedish outcomes) rather than the doubling in mental health problems and 20%-of-GDP increase in government debt that the UK actually experienced.

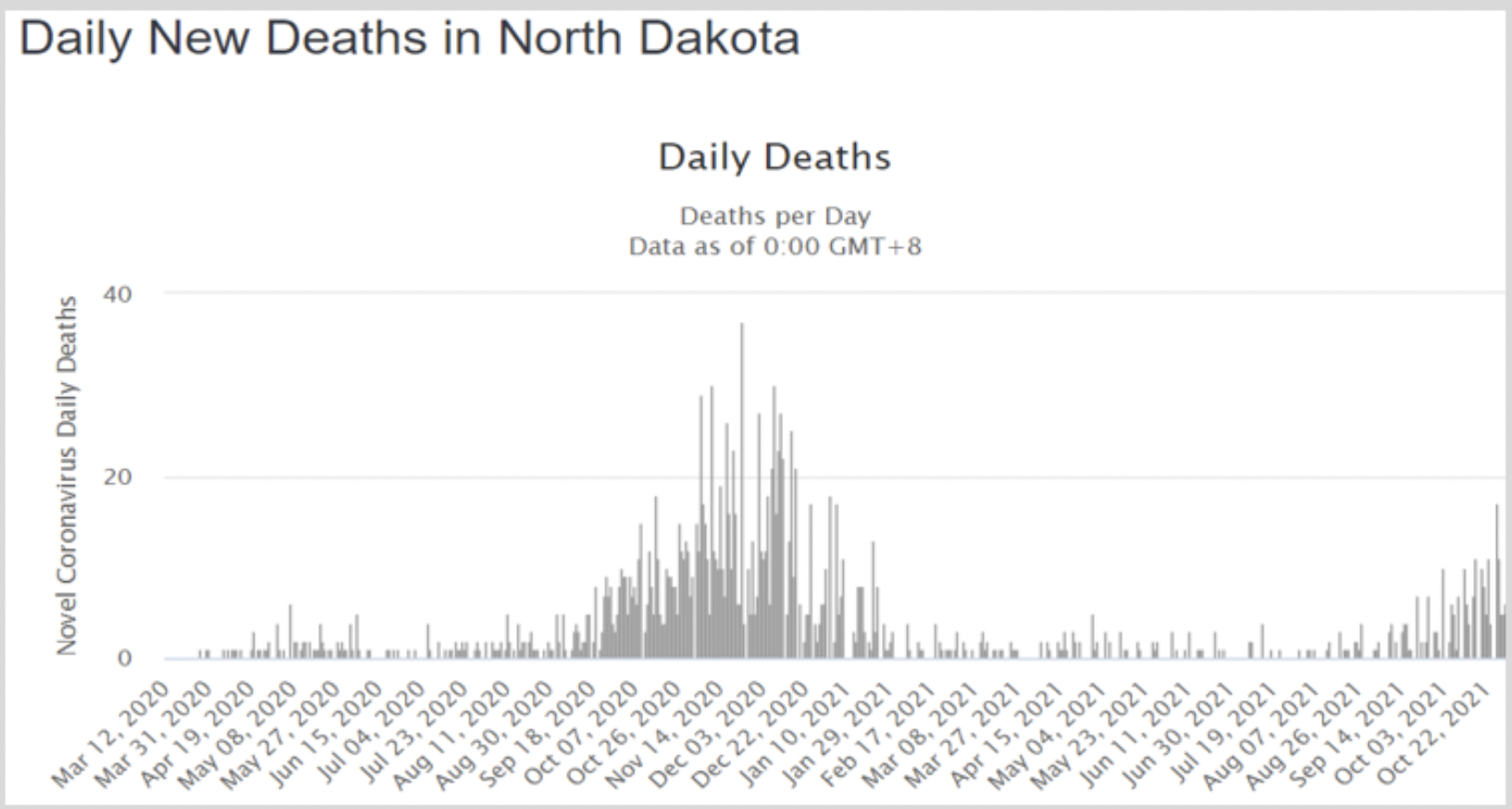

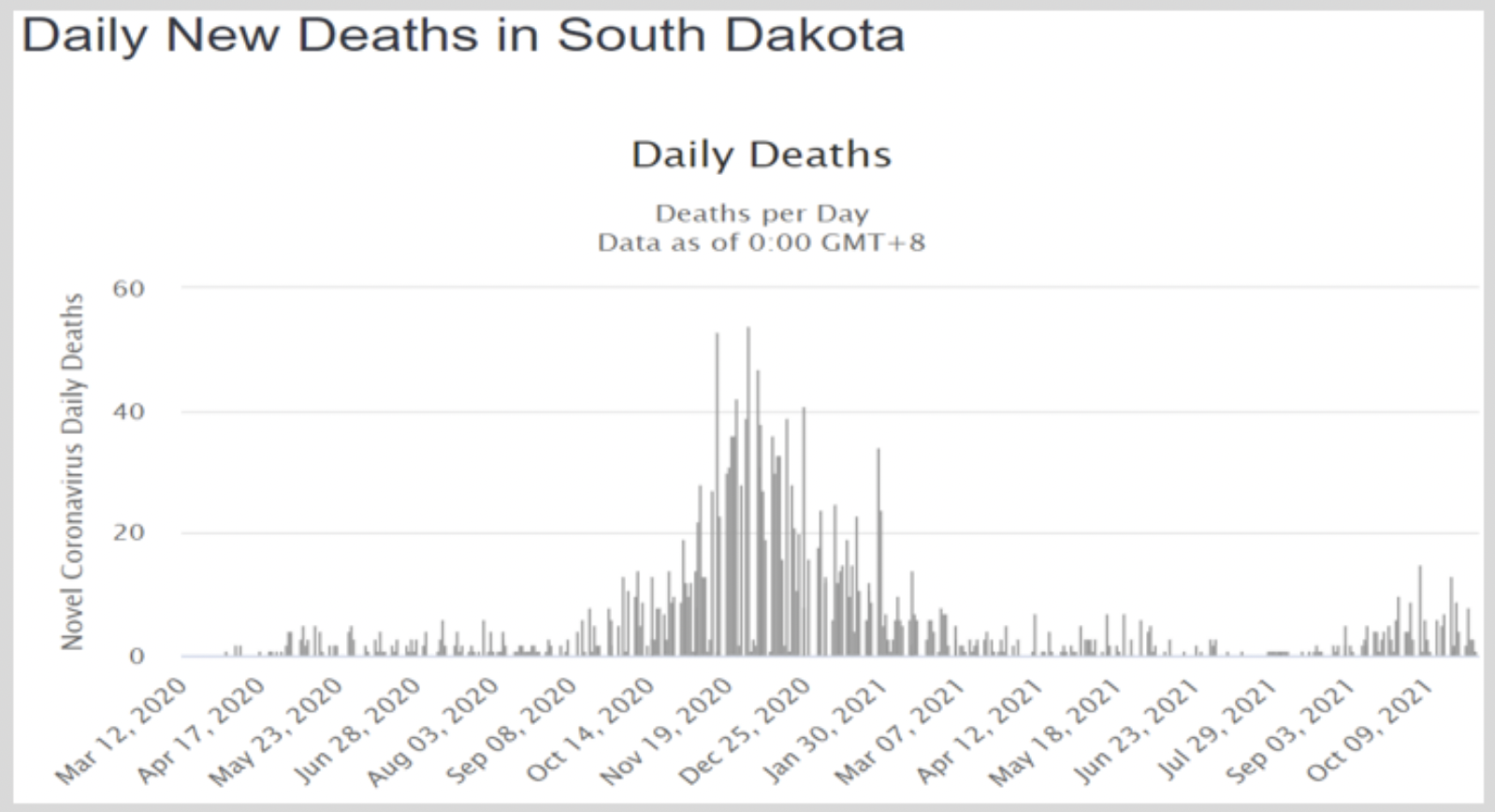

For the US, we can do better, because of the high diversity of policies between states. We can make reasonable comments about the costs and benefits of different Covid policy constellations by comparing high-lockdown states like New York and California with low-lockdown states such as Florida, Texas, and South Dakota. Brownstone Institute has compiled a database of over 400 studies that have identified few positive, and even negative, net effects of lockdown policies and other restrictions.

2(c) The approximate magnitude of Covid policy costs and benefits

The most important and useful thing that the well-being-based cost-benefit analyses of Covid policies has delivered is a sense of the magnitude of different effects. We have learned where to look for the damage, and now have a set of rules of thumb about what is harmful, what is benign, and what is helpful that can be applied in settings ranging from the country to the village to the company.

Seven WELLBY papers have estimated Covid policy costs and benefits, using data respectively from the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the world as a whole. We provide the bottom line of the study as well as the essential breakdown of where they estimated the main costs and benefits to be, which differs quite a bit over time, as with more elapsed time the effect that is yet to come in the future relative to damage already sustained reduces. The purpose is to indicate the main sources of costs and benefits, and the relative magnitude to which different things matter for the bottom line.

The following table presents these estimates.

| Country and Author/s | Summary finding | Highlights of the analysis |

|---|---|---|

| UK: De Neve, J. E., Clark, A. E., Krekel, C., Layard, R. and O’Donnell, G. (2020), ‘Taking a Wellbeing Years Approach to Policy Choice’, British Medical Journal, 371, m3853-m3853. | Their preliminary analysis of April 2020 suggested that the UK lockdowns might potentially be beneficial until 1 May 2020, but after that they would increasingly lead to greater net harm to society. To reach that conclusion, they effectively presumed that government services were about 20 times less effective at buying well-being than has been found in the literature (which reduces the importance of the economic effects). | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 6 years in good health. The costs of lockdown in April 2020 are appx in this proportion: reduced income (30%), increased unemployment (49%), reduced mental health (12%), reduced confidence in government (6%), reduced schooling (3%). The benefits of lockdowns in April 2020 are in this proportion: reduced SARS-CoV-2 deaths (84%), reduced road deaths (3%), reduced commuting (5%), reduced CO2 emissions (4%), improved air quality (4%). The costs of lockdowns worsen with a longer duration but benefits do not increase proportionately. |

| UK: Frijters, P., Foster, G. and Baker, M. (2021), The Great Covid Panic. Brownstone Institute Press, Austin, TX. | The costs of UK lockdowns were at least 28 times greater during 2020 than any benefits (illustrative calculation: a single month of UK-style lockdown in the developed West is estimated to cost around 250% of the entire loss represented by 0.3% of the population dying of Covid). | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 3 years. The costs of lockdown are mainly through reduced IVF babies (11%), reduced mental health (life satisfaction) (33%), future health problems (10%), government debt (41%), and harms to child education (5%). The benefits are mainly the Covid deaths averted (97%) and long Covid averted (3%). The lockdown harms increase each month, but benefits do not (since the pool of those at risk does not increase cumulatively). |

| Ireland: Ryan, A. (2021), ‘A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the COVID-19 Lockdown in Ireland’, Social Science Research Network Working Paper. | “It was found that the costs of the lockdown are 25 times greater than the benefits. Furthermore, each of the individual costs taken on their own are greater than the total benefits of lockdown.” | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years. In a conservative scenario, the costs of lockdowns are in this proportion: Reduced government spending on healthcare (35%), well-being loss (isolation) (49%) and increased unemployment (17%). Benefits are Covid deaths prevented. Lockdown costs increase over time since unemployment increases; benefits remain the same. |

| New Zealand: Lally, M. T. (2021), ‘The Costs and Benefits of Covid-19 Lockdowns in New Zealand’, MedRxiv: The Preprint Server for Health Sciences. | Lally finds that lockdowns may have saved 1,750 to 4,600 Covid deaths at a cost “at least 13 times the generally employed threshold figure of $62,000 for health interventions in New Zealand… [T]he lockdowns do not then seem to have been justified by reference to the standard benchmark.” | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years. The paper estimates that 18,400 QALYs are saved from Covid by lockdowns but 3,800 QALYs are lost from the long-term health effects of unemployment. Costs are the GDP foregone by lockdowns net of medical costs for Covid and any output produced from working from home. This yields $1.04 million per QALY saved against a benchmark of $0.062 million. |

| Canada and the world: Joffe, A. (2021), ‘COVID-19: Rethinking the Lockdown Groupthink’, Frontiers in Public Health, 9, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.625778 | The paper conducts a CBA for Canada and finds that the harms of lockdowns in WELLBYs are a minimum of 10 times the benefits. A broad CBA for the entire world finds that the harms would be a minimum of 5 times and up to 87 times the benefits. | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years. For the minimal (5 times harms) “world CBA,” the paper allocates 66% of the costs of lockdowns to recession, 15% to unemployment and 18% to loneliness. Their sum is five times greater than Covid death WELLBYs saved by lockdowns. For the Canadian CBA, the paper allocates 36% of the costs to recession, 8% to unemployment and 55% to loneliness. |

| Australia: Foster, G. (2020), ‘Cost-Benefit Analysis Executive Summary’, Parliament of Victoria. | The CBA finds that “the minimum cost of a month’s worth of wholesale lockdown is estimated at 110,495 QALYs…the estimated benefit of locking down “ad infinitum” (not only per month) is 50,000 QALYs”. Over the course of two years, this yields a net harm of at least (110495*24/50000), i.e. 53 times any benefits. | Assumption: The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years. The CBA allocates costs of lockdowns to reduced well-being (75%), reduced economic activity (23%), increased suicides (1%) and foregone wages of children from disrupted schooling (1%). |

| Australia: Foster and Sabhlok (2022). Executive Summary of “Do lockdowns and border closures serve the ‘greater good’?” | The CBA finds that the costs of Australia’s Covid lockdowns have been more than 60 times greater than the benefits they delivered. | The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years (Covid lives saved is a net figure after deducting deaths that could not be prevented by the lockdowns). The costs of lockdowns are allocated as follows: lost GDP and increased expenditure (49%), lost well-being (44%), non-Covid excess deaths in 2020 and 2021 (1%), and the present value of future costs (reduction in the general lifespan of all Australians, lost future productivity of children born during lockdowns, and lost future productivity of children of school age during lockdowns) (6%). |

| Frijters, P. and Krekel, C. (2021), A Handbook for Wellbeing Policy-Making: History, Theory, Measurement, Implementation, and Examples. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. | The book finds that “the ‘containment and eradication’ scenario is almost 3 times more costly in terms of well-being than the laissez-faire, business-as-usual scenario. And that ratio uses assumptions and numbers which are blatantly pessimistic about ‘business-as-usual’ and blatantly optimistic about ‘containment and eradication.’ Under more reasonable assumptions the costs are easily fifty times larger under the containment strategy than the business-as-usual strategy.” | The average person saved from a Covid death would live another 5 years. There is an assumption that lockdowns lasting only a few months would save 27 million lives but 3 million would die nevertheless. The costs of lockdowns are allocated as follows: unavoidable loss of life from Covid (3.5%), general reduction in population well-being (56.7%), unemployment (21%) and loss of government revenue (18.7%). |