The first book I ever read on public policy was Compassion Versus Guilt. A collection of columns by the great Thomas Sowell, it was what I regularly referred to on all questions economic toward the end of high school, in college, and well beyond. I have it to this day, and it informs my thinking to this day.

In many ways Sowell’s collection is a look back in time. Thanks to the internet, these kinds of compilations aren’t as common nowadays. This is unfortunate, but at the same time some writers are so prominent and popular that they still rate this kind of publication. Washington Post columnist extraordinaire George Will is one of them. Thank goodness. His latest collection of essays, American Happiness and Discontents: The Unruly Torrent 2008-2020 is nothing short of spectacular. Though a little under 500 pages, I read it in a few sittings so unputdownable was it. Every column had me wanting more, which meant a few late nights and early mornings in a very short, very busy 8-day stretch.

Up front, it’s useful to write about the person who put American Happiness together. While the book’s tone is much more optimistic than Will’s similarly excellent but less cheery The Conservative Sensibility, Will doesn’t hide his disdain for some of the consequences of what he would undeniably view as progress. He laments that “New technologies” have produced “a blitzkrieg of words, written and spoken.” Worse, the words in Will’s mind are more and more “shouted by overheated individuals who evidently believe that the lungs are the seat of wisdom.”

Will’s book is an antidote to the present level of discourse, and most fun for readers eager to learn well beyond policy is that so much of Will’s commentary springs from the voluminous books he consumes with great vigor. As he puts it, “The more fuss is made about new media,” the “more I am convinced that books remain the primary transmitters of ideas.” In short, this most excellent of books is in many ways about books, and will have the reader ordering all manner of new ones after reading commentary that springs from the reading of them by Will. American Happiness teaches a great deal, but also sets the stage for a great deal more learning.

In the introduction, Will writes that “Were I a benevolent dictator, I would make history the only permissible college major in order to equip the public with the stock of knowledge required for thinking clearly about how we arrived at this point in our national narrative.” The quip is very telling mainly because Will’s book imparts so much knowledge. Easily the best part of what is so good on so many levels is what the reader will learn about the world, past and present. In other words, to refer to this as solely a policy book is the equivalent of referring to Warren Buffett as a candy billionaire. Readers will see why this is true in the first section, The Path to the Present.

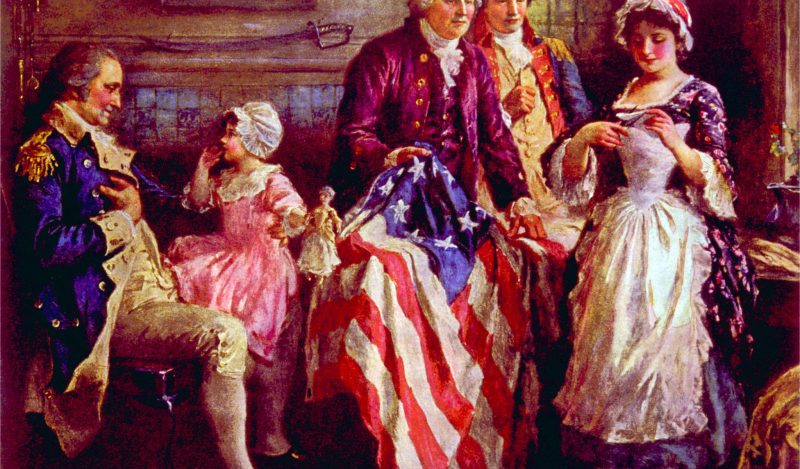

In the second column, “A Nation Not Made by Flimsy People,” Will features the writings of historian Rick Atkinson, and his account of the Revolutionary War. It’s a vivid reminder of just how brutal life used to be. Will writes that “Inaccurate muskets often were less lethal than primitive medicine inflicted on the victims of muskets, cannons, and bayonets. Only the fortunate wounded got ‘their ears stuffed with lamb’s wool to mask the sound of the sawing.’” The sawing was the amputation of legs that was commonplace, and the consequences of which only half survived. There are so many ways of looking at this, but given the times we live in, what Will conveys is a reminder that economic progress is easily the biggest enemy that death, disease and pain have ever known.

This is important when it’s remembered that politicians of all ideologies chose economic contraction as their virus-mitigation strategy in 2020. To read American Happiness is to see even more clearly just how abjectly foolish this approach was. Indeed, even by the early 20th century (“The Coronavirus’s Disturbing Lesson”), “37 percent of American deaths were from infectious diseases” versus 2 percent today. As Will notes in The Conservative Sensibility (review here), even by the 1950s the biggest line item on hospital budgets was bed linens. Fast forward to the present, Will quotes polymath writer Bill Bryson as writing in The Body: A Guide for Occupants, that “We live in an age in which we are killed, more often than not, by lifestyle.” Translated for those who need it, remarkable economic progress has produced the resources that have made it possible for doctors and scientists to erase or shrink myriad life-enders that used to menacingly stalk the living.

Even better, this same economic progress has had another salutary impact on health. Will brings to mind Oxford’s Sunetra Gupta (or she brings to mind Will) when he writes that “The interconnectedness of the modern world, thanks in part to the jet engine’s democratization of intercontinental air travel, deters the weaponization of epidemics that the connectedness facilitates.” In other words, people bumping into each other from around the world (the opposite of “social distancing”) have driven enormous strides of the immunization variety over the decades. Rich is healthier. Period.

Later in American Happiness, Will questions the tendency among the truck-driver set on the Right to disdain masks, but it’s almost immaterial. His book connects the dots on the obvious correlation between economic health and human health. It’s a reminder that freedom on its own is a virtue (lest we forget, we humans are the market, and our freely arrived at decisions produce crucial information), after which we know clearly that free people produce the prosperity that crushes what would otherwise kill us. Amen.

Will’s focus on history and the wars that shaped history in The Path to the Present plainly instruct in ways beyond the folly of a political response to a virus. There’s a tendency to glamorize war that Will rejects, but also to elevate the average over the uncommon. Will doesn’t fall for it. Referring yet again to “A Nation Not Made by Flimsy People,” Will thankfully disdains the “sentimental idea that cobblers and seamstresses are as much history-makers as generals and politicians.” No, they’re not. Nothing against the average, but average people could never have created something as brilliant as the United States. In Will’s words, “No George Washington, no United States.” Applied to the present, it’s fun for an increasingly populist Right to get all weepy about small businesses as the alleged “backbone” of the U.S. economy. Nonsense.

About what’s small, count this reviewer as reverent of most every business, regardless of size. Any business is a bit of a miracle born of immense courage when it’s remembered that an entrepreneur in the extravagantly prosperous U.S. is trying something new on the wildly arrogant assumption of a need not presently being met by the most enterprising people on earth. At the same time, a walk through any shopping mall or shopping center of any kind is a loud reminder that big businesses give life to the small ones that cluster around them. Channeling Will, “No Big Business, no small business.”

Importantly, it’s about more than small versus big. Arguably the most dangerous form of nostalgia is that of the work kind. Presidents who, in Will’s wise estimation, “permeate the national consciousness to a degree that isn’t healthy,” routinely promise to bring the jobs of the past back. It’s the path to decline. In Will’s “Human Reclamation Through Bricklaying,” we learn that in the 1920s Pittsburgh was “America’s ninth most populous city” versus sixty-sixth today. Jobs aren’t created, rather they’re a consequence of investment. Investment follows people. The talented people, the unequal people, have a tendency to run from the present and past. The investment once again follows them. What romanticizes Pittsburgh in the minds of politicians and dopey sportscasters repels investors. Will notes that Pittsburgh has largely “put aside smokestacks and remade itself around technology and health care,” but its past decline relative to what it was is a cautionary tale about stasis, or worse, economic blasts to the past.

About the truth that Pittsburgh’s history bluntly tells, the lessons aren’t just for foolish politicians. The Fed obsessed claim to this day that stock-market rallies are a consequence of central bank “money” creation. Oh please. Such a view insults reason, and it presumes that the propping up of the present would excite investors looking deeply into the future. No, not at all. When self-proclaimed free-market types tie market exuberance to central bankers they’re unwittingly revealing themselves as Barack Obama (“you didn’t build that”), Right-Wing edition.

What about war? Will has read (and watched) so much about it, and readers will learn so much about the hell that is war from American Happiness. About PBS’s American Experience documentary ‘The Great War,’ Will tells readers to “Watch it and wince.” Read Will’s review of it (“America’s Dark Home Front During World War I”) and wince at the horrors of this most needless of wars. Then turn the page to “The Somme: The Hinge of World War I, and Hence of Modern History,” to read about how “the worst manmade disaster in human experience” was the “incubator of Communist Russia, Nazi Germany, World War II,” not to mention how the battle for “that little stream” known as the river Somme killed “eight British soldiers per second” in the early hours of July 1, 1916, and 19,240 by nightfall.

What to say about all this? At the very least it should be said that the history of the use of government power indicates that those in its employ have no basis for doing much of anything “for your own good.” It’s a waste of words, but government is incompetence. Always. And the incompetence isn’t limited to the fifty states. See above.

Which brings us to an essential quote Will gives us from Calvin Coolidge, who while president “was alarmed that economic growth was producing excessive revenues that might make government larger.” This truth will be discussed again in this review, but for now it should be said that government spending is a tax. A big one. An economy is a collection of individuals, and the bet here is that individuals like Jeff Bezos would work feverishly at a lot of different tax rates. The previous statement isn’t meant to justify high rates of taxation (not at all), but it is to say that the much bigger barrier than tax rates to entrepreneurial and commercial endeavor is government spending (without regard to the distraction that is “deficits” or “surpluses”) itself.

When governments spend, it’s Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell being handed power to allocate precious resources versus Peter Thiel, Fred Smith, and Elon Musk. The government spending is by its very description an economic somnolent, at which point it would be useful for self-proclaimed supply siders to rethink their excitement about the allegedly positive revenue effects of tax cuts. While it may be empirically true that reduced taxation results in increased intake for Treasury, this truth isn’t an economic or freedom positive. That it isn’t should not be construed as a call for higher rates of taxation, but it is a call for supply siders to get serious about true policy innovation that would shrink rates of taxation while at the same time shrinking the federal government’s tax revenues.

This isn’t to say that all government spending is necessarily bad, or even extra-constitutional. Certainly the Constitution calls for the federal government to provide a common defense, and it’s a joy to read Will’s 2018 column titled “The Thunderclap of Ocean Venture ’81,” an account of John Lehman’s book (Oceans Ventured: Winning the Cold War at Sea) about Ronald Reagan’s call for an expanded U.S. Naval ship presence around the world, including “U.S. aircraft carriers operating in Norwegian fjords.” This was something the Soviets were not militarily or financially prepared for. Will writes of how the Soviet general staff “told Gorbachev that they could not defend the nation’s northern sector without tripling spending on naval and air forces there.” As Will goes on to write triumphantly, “Thus did the Cold War end because Reagan rejected the stale orthodoxy that the East-West military balance was solely about conventional land forces in central Europe.”

Still, the mildly sentient among us recognize that the triumphs born of government spending are very minor relative to the losses. About the long fingers of politicians, Will rightly devotes a lot of space to the horror that is civil asset forfeiture. The latter is the process whereby governments with relatively unlimited resources (“Philadelphia’s ‘Room 101’”) take “property without trial, and the property owner must wage a protracted, complex, and expensive fight to get it returned.” The examples Will cites are more than disturbing, at which point it’s hard not to ask why government is always the victor when citizens win (found, or invest in a wildly successful company), lose (see civil asset forfeiture), or something in between along the lines of merely earning a paycheck?

It’s likely no surprise to anyone reading this review that Will is a skeptic of government power. He most notably yearns for a much smaller presidency, and presidents not interested at all in our problems, but his yearning for a smaller State is not limited to the Presidency. Will would also like to see a reduction in the majesty that is government on the state and local level. Where it really hits home is in his discussion of Mississippian Joey Chandler (“’Depravity’ and the Eighth Amendment”); Chander spending life in prison for a murder committed when he was quite a bit younger. Will doesn’t excuse what Chandler did as much as he believes humans are capable of rehabilitation. Will is not excusing hideous acts as much as it’s apparent that he decries one-size-fits-all law in much the same way that reasonable economic thinkers disdain one-size-fits-all rules and regulations. In Will’s estimation Chandler has changed more than a lot since a grievous error committed in his teens, he adds that the Constitution’s 8th Amendment exists to protect the citizenry from “cruel and unusual punishments,” but that Mississippi’s judicial system is using its powers to disregard the Amendment. Like so many libertarians, Will seems to desire more activism in the federal judiciary whereby the meaning of the Constitution is regularly exalted as a way of limiting the power of state and local governments to essentially dictate the outcome of a human life. Sadly, the Supreme Court decided in 2019 to deny Chandler’s petition “asking the court to review his case.” Will plainly disagrees with the Supreme Court’s decision, and the view here is with good reason. If those in government on the federal level aren’t actively protecting our individual rights, then their minds are wandering.

About gerrymandering (“The Court and the Politics of Politics”), Will writes that it’s “as political as lemonade is lemony.” Where it gets really interesting is when he makes the point that the “Constitution is silent regarding limits on state legislatures’ partisan redistricting practices and is explicit regarding Congress’s exclusive power to modify these practices.” Despite this, he calls for restraint here. With hard-to-argue-with reasoning: “If the court nevertheless assigns a portion of this power to itself, its condign punishment, inflicted after each decennial census, will be avalanches of legislation arising from partisan unhappiness about states’ redistricting plans.” The result would be even greater politicization of the Supreme Court, particularly in the eyes of partisans, such that “its reputation as a nonpolitical institution will be steadily tarnished.”

On the subject of science, Will is a joy. His skepticism about expertise and grand policy responses as a consequence of expertise expressed is a lot of fun to read. He quotes 1998 Nobel Prize winner Robert Laughlin (“The Pathology of Climatology”) as observing that damaging planet earth is “’easier to imagine than it is to accomplish.’ There have been mass volcanic explosions, meteor impacts, and ‘all manner of other abuses greater than anything people could inflict, and it’s still here. It’s a survivor.’” In the column preceding the aforementioned (“A Telescope as History Teacher”), Will writes of “Our Milky Way galaxy, where we live,” that “probably has 40 billion planets approximately Earth’s size.” Oh wow, we’re so small and insignificant. At least that’s how this reviewer reads Will’s analysis. Back to Laughlin, “the earth doesn’t care about any of these governments or their legislation.” Yes! The arrogance of the global warming movement is astounding. Remarkable as we humans are, we’re the proverbial ant on the elephant’s enormous behind, and even the latter probably understates our significance to planet Earth’s health.

Were there disagreements? Here and there. In “Crises and the Collectivist Temptation,” there’s total agreement with Will that “unconstrained government meddlesomeness” surely “prolonged the twelve-year Depression,” but total disagreement that it lasted “until rearmament ended it.” Referencing a Calvin Coolidge quote from earlier in this review, he was “alarmed that economic growth was producing excessive revenues that might make government larger.” Governments can never stimulate growth with spending precisely because their spending is always and everywhere a consequence of taxable economic activity. The popular notion that political allocation of resources ended relative economic desperation (by global standards, the 1930s U.S. economy was booming) amounts to double counting. Much worse, it ignores the horror that is war, horror that Will himself does not ignore. Over 800,000 Americans met an early end as a consequence of World War II, not to mention the many millions who died way too early around the world. The only closed economy is the world economy, and that which extinguishes the human life without which there is no economy is always an economic depressant. The booming unseen for the world economy absent this hideous spawn of the mis-named “Great War” is hard to fathom, but it’s very safe to say that the U.S. and the world would be much more prosperous today if World War II never happened. Weapon-making, wealth destruction, maiming and killing did not free us from the 1930s.

Will spends a fair amount of time on university education, and admittedly very unsettling instances of Lefty types who are seemingly offended by everything. This isn’t to cast doubt on the veracity of the examples of childish childishness, but it is to say that these examples surprise in my estimation because they’re somewhat rare. To visit college campuses today is to observe that kids are the same as they’ve ever been: they’re there to make friends, meet girlfriends and boyfriends, have lots of fun, and to emerge mostly intact four years later with jobs. The kids are alright.

As for the cost of a college education, Will cites the very excellent Glenn Reynolds and his assertion that government subsidization of college education has resulted in soaring tuition. Without defending government’s involvement in college education for even a second, the view here is that the Right well overstates the tuition impact, particularly among relatively elite colleges and universities. Evidence supporting this claim comes from tuition costs at private high schools across the U.S. They’ve risen exponentially over the decades too, and without the federal subsidies. To a high degree college education is very expensive stateside because it can be; because U.S. colleges and universities are palaces desired by increasingly well-to-do people the world over.

Still, the quibbles are minor. On the subject of what got us out of the Great Depression, it should be stressed that my views are fringe. This is a soaring book. Much as The Conservative Sensibility was wondrously interesting and informative, it was much gloomier. With American Happiness, there’s a sense that Will himself is happier about the world. This is not to say that he’s thrilled about where the proverbial “we” are in total (see the introduction), but this curation is not that of someone who sees the U.S. in decline. There are a number of examples supporting the previous assertion, but the one that stood out the most came from “An Illinois Pogrom,” in which Will reviewed a book by Jim Rasenberger (America 2008) that included an account of a horrific, multi-evening, white-on-black lynching, looting, and beating in response to a false rape accusation lodged by a white woman about a black man. About this multi-layered tragedy that took place in Springfield, IL, Will optimistically observed that it “all occurred within walking distance of where, in 2007, Barack Obama announced his presidential candidacy.” About Obama’s announcement nearly 100 years after the horrors described in his column, Will noted that “it illustrates history’s essential promise, which is not serenity – that progress is inevitable – but possibility, which is enough. Things have not always been as they are.” No, they haven’t. Nostalgia is economically crippling, and in a country like the U.S., it’s life crippling. It’s wasteful. What those not lucky enough to be American would give to have our problems.

In a Wall Street Journal interview about American Happiness, Will was asked about his favorite column within. It’s “Jon Will at Forty,” which is about his oldest son who has Down syndrome. Will’s account of his son’s life, and how well-lived it has been is beyond uplifting. He hasn’t let the limits he was born with deter him from pursuing a great and happy existence, including work for his beloved Washington Nationals for whom “he enters the clubhouse a few hours before game time and does a chore or two.” Jon Will attends every Nationals’ home game “in his seat behind the home team’s dugout,” Jon Will “just another man, beer in hand, among equals in the republic of baseball.” And it’s not just his father’s description of his son that is so moving. Will’s columns about Down syndrome will cause every existing and prospective mother and father to rethink the very common practice of pre-screening for the syndrome. Of all the columns in this great book, these are the ones I’ve talked about the most with my wife, who is also the mother of our two kids. When this review is finished such that I can hand this essential book off to her, those will be the first columns she reads.

This most brilliant of books ends with a gut-wrenching account of what it’s like for casualty assistance calls officers (CACO) in the military, who are the individuals charged with letting family members know first about the deaths of loved ones. To say it’s powerful brings new meaning to understatement, after which it’s personal. Will’s longtime and indispensable assistant to whom American Happiness is dedicated, Sarah Walton, received one of these calls after her husband (Lieutenant Colonel Jim Walton, West Point Class of 1989) was killed in Afghanistan in 2008. Oh wow, it’s painful. What else can a reader say?

The only thing that can be said is what this reviewer has said over and over again since opening this remarkable book eight days ago: it’s thoroughly spectacular. I’m sad to see it end. In these eight days I’ve carried it around with me because I want people to ask about it in hopes that I can tell them about a book that they couldn’t possibly not love.

Reproduced from the author’s Forbes column

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.