For $1.95, I bought the Complete Harvard Classics set in 51 volumes, plus a 20-volume fiction set. I was a bit annoyed a few weeks later when, showing my Dad how to buy it on Kindle, the price had dropped to $1.15.

However, even at the inflated price I paid, I think I got my money’s worth. I’ve only scratched the surface – I don’t think I could read everything that’s included if I spent every waking hour reading until I shuffle off this mortal coil. But I’m making headway nevertheless. Somehow, in a sort of minor miracle given the circumstances at the time, I was able to fulfil a long-held dream to travel the Kimberley and the Pilbara and widely elsewhere in Western Australia in 2021. Travelling 23,500 km, there was plenty of time to read, either in the car, or by the campfire, or on the beach. My Harvard Classics were rarely far from hand. These days I hardly leave home without it.

Familiar names like Jane Austen, Dickens, Bunyan and Milton – gateway drugs, if you like – gave me plenty to chew on; a dose of reality expressed in so many varied ways. Underneath the stories, the truth shines out irrepressibly – women and men doing what women and men have always done. Love, betrayal, bravery and cowardice, good and evil all emerge, incarnate, for all to see. In your face. Literary stereotypes of the human condition – encountered in fiction, enabling recognition in real life. The works scream out: “This is what greed looks like, This is what lust and betrayal look like.”

Less well known to me was Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed, an epic tale of treachery and power, tyranny and heroism, and more. All distilled to the point of combustion as you read it. Screaming out again: “This is what corruption looks like, this is what fear does to the mob.”

Watching the TV in the last few years was like watching caricatures of corruption and fear and contempt and cowardice as our political and bureaucratic overlords preened and posed and pretended to have anything other than their own interests at heart. Did I recognise the caricatures because of the stories I’d read? Maybe. But they were unmistakable.

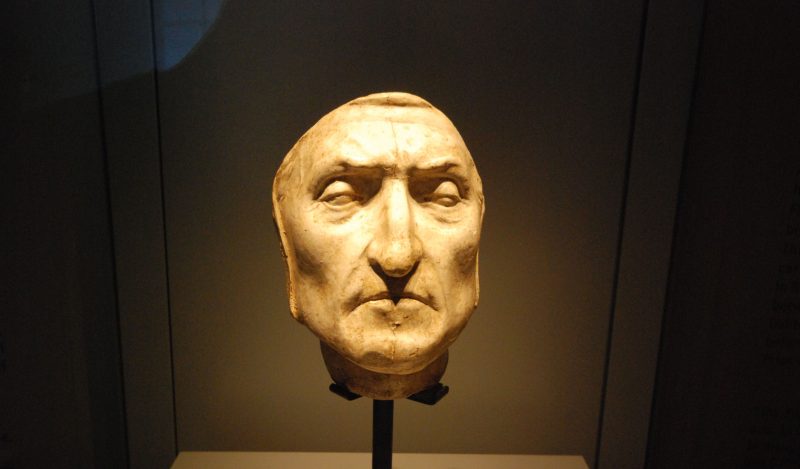

It was Dante that took the cake though.

I’m not really sure about Dante’s theology as expressed in his Divine Comedy, but the central idea of part I, The Inferno, is very, very appealing. We watch the author tell his tale of finding himself lost in a wood, then meeting a poet from another time, who guides him on a tour of Hell, all the way down, through 9 circles, each circle dedicated to a certain type of sin, more horrendous the further down you go.

According to Dante, the horrors started for those in Limbo (the unbaptised and virtuous pagans), and deepened according to the sequence Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Wrath, Heresy, Violence, Fraud, and Treachery.

Dante’s conception of Hell finds the sinners, many of whom he knows as contemporaries, being subjected to eternal punishments which perfectly, exquisitely, justly fit the crimes. Schadenfreude on steroids. It seems somehow wrong to imagine modern day characters finding their own special place to spend eternity. Wrong, but irresistible. Delicious.

In times gone past, cadets at newspapers were often given the task, on ‘slow news days’ of updating the obituaries for as yet living public figures. That way, they were only ever a sub-editor away from have the requisite number of words of fawning adulation, thinly-veiled contempt, or something in between depending on the disposition of the mogul-in-charge. The article could be rolled out when the figure in question died, (or resigned in disgrace, now a quaint relic of a bygone era when shame, not pride, was a thing.) I imagine this cadet chore is becoming more of a burden given the trending #diedsuddenly rash of heart attacks and strokes – any one of which could be a celebrity who needs a couple of column inches.

So the cadet, faced with a grumpy subby, picks a random politician from the gallery of rogues and begins to map out the politician’s life and times. In fact, he cunningly sets out to draft a one-size-fits-all obituary, using a composite fictional character. Then he can change a few pronouns here and there, a date or two, and re-use the thing over and over. He gives his dead man a name: let’s call him ‘Andrew Daniels.’ No relation to any person living or dead.

Careers in any walk of life are sometimes predictable – from doctor to medical administrator to Chief Health Officer to Governor of Queensland say, or doctor to reality TV to public health to Chief Health Officer to Victorian of the Year, or fish-and-chip shop worker to political researcher to soup kitchen volunteer to third-time-lucky MP to NZ Prime Minister to student of online extremism. Totally normal.

Our mythical ‘Andrew Daniels,’ too, has a predictable arc of history: Arts graduate. Political staffer. State MP. Health Minister. Premier. Not a bad record on this worldly ledger. So far so good. Plenty of column inches there, to satisfy the sub-editor.

The typical obituary, understandably, outlines achievements and setbacks, but frames a life’s work with the worldview that you only live once, and that death is indeed the final curtain. So it doesn’t really matter what you do, as long as what you are doing right now is either making you happy, making you money, or lining you up for the next job.

Dante took a different line – making the point time and time again that death is not the final curtain, and a career spent in worldly pursuits will indeed land you the perfect situation for eternity. Imagining one’s own Curriculum Vitae being read out at the gates of hell prior to being escorted to the appropriate place and punishment lends a certain frisson to one’s day – keeps one on one’s toes, you might say.

‘Andrew Daniels’ might not be so happy, in the end, with this other ledger. A quick glance, according to Dante’s checklist, might make him if not disconcerted, then far from being concerted.

Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Wrath, Heresy, Violence, Fraud and Treachery. Where does one start?

Shooting protestors in the back? Tick. Devouring iced donuts? Tick. Scolding reporters who dare ask a pointed question? Tick. Denouncing football club CEOs for daring to be a Christian? Tick. Signing secret deals with foreign governments? Tick. Can’t recall? Tick. Tick, tick, tick….

The wait time at the head of the queue while the rap sheet is read out is likely to be longer than average. I’m not here to judge ‘Andrew Daniels.’ For one thing, ‘Andrew Daniels’ is a fictional character. For another, that job has been taken.

I suspect the only really capital-T truthful accounts of this period will come many years hence; and they will be notionally fictional. Fiction is likely to be the last redoubt in the escalating struggle with censorship. Within the pages of these yet-to-be-written novels, pseudonymous but identifiable characters larger than life, and larger than death, will roam the country, molesting it at every turn; battles will be fought in the streets and treachery will lurk in the halls of power; intimate tragedies will be played out in homes, portraits of orphans and widows sketched with wrenching pathos. Perhaps the overall story will be one of deluded folly, like Don Quixote, or one of cold revenge, like The Count of Monte Cristo.

I can’t quite bring myself to imagine the whole hot mess turned into a musical, though, like Les Miserables. That’s a bridge too far. But I can imagine a mythical character like ‘Andrew Daniels’ featuring as a loathsome villain.

Where is our current day Cervantes, or Dumas, or Hugo? Perhaps they’re already squinting over candle-lit manuscripts in a garret somewhere, secreting the forbidden samizdat under a broken floorboard, as they labour for the future of generations to come. I hope so.

Reposted from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.