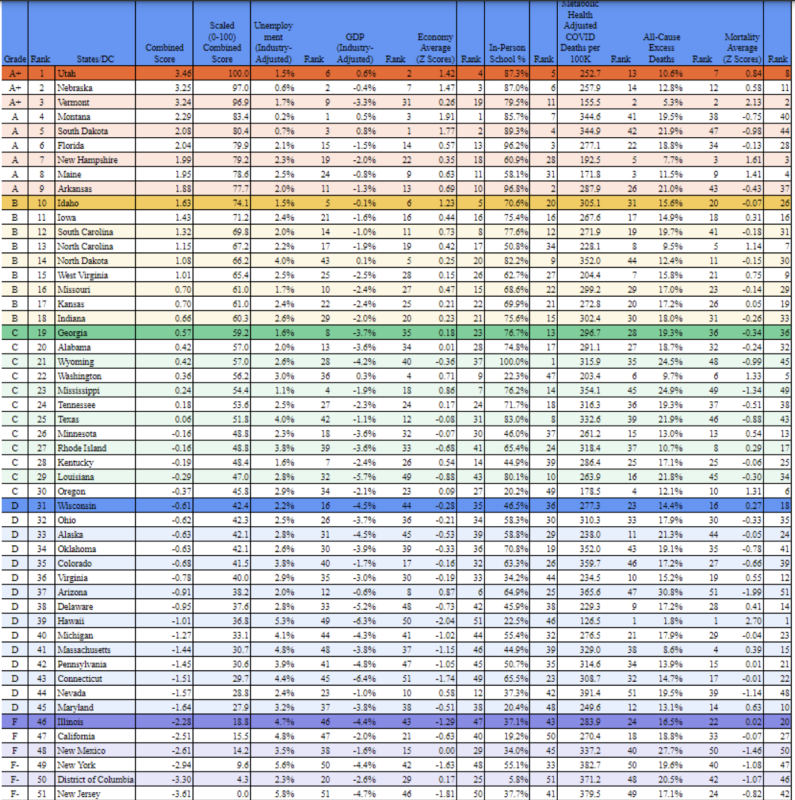

Utah, Nebraska, and Vermont: A+.

Florida, South Dakota, Maine: A.

Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland: D.

California: F.

New York, New Jersey, District of Columbia: F-.

After more than two years since the outbreak of Covid-19 in the United States, the time has come for a final analysis of public health outcomes on a state-by-state basis. That is what this new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research seeks to do.

Its authors Phil Kerpen-President of the Committee to Unleash Prosperity, Stephen Moore-an economist at the Heritage Foundation, and Casey Mulligan-University of Chicago professor and chief economist during the Trump administration, may seem like partisans, but their analysis is sound. They use three factors that everyone should care about: public health outcomes measured by adjusted mortality rates, economic performance, and keeping schools open. They conclude that lockdowns had almost no discernible effect on mitigating Covid deaths but led to substantial damage to the economy and educational experience.

These effects-based variables are some of the most logical and consequential issues to consider, which differs significantly from a UC Berkeley report in 2021. That report placed states like California at the top and South Dakota at the bottom. The report measured state responses based on case counts, death rates, and testing rates. In essence, that report attempted to measure the effort exerted by a state’s government as a measure of excellence rather than taking into account the ultimate societal consequences.

Some have criticized the American federalist system of 50 different public health responses for 50 individual states as dangerously inconsistent. However, having so many different public health experiments prevented the country from blindly walking in the wrong direction and provided empirical evidence on whether the slogans, narratives, and edicts of the public health establishment held water in practice.

Mitigating Mortality

Lockdowns did little if anything to prevent Covid deaths. It is widely established that the virus does not care about the law and it will find a way to spread regardless of the policy response. On the matter of lockdowns and mortality, this paper essentially adds yet another nail to the coffin.

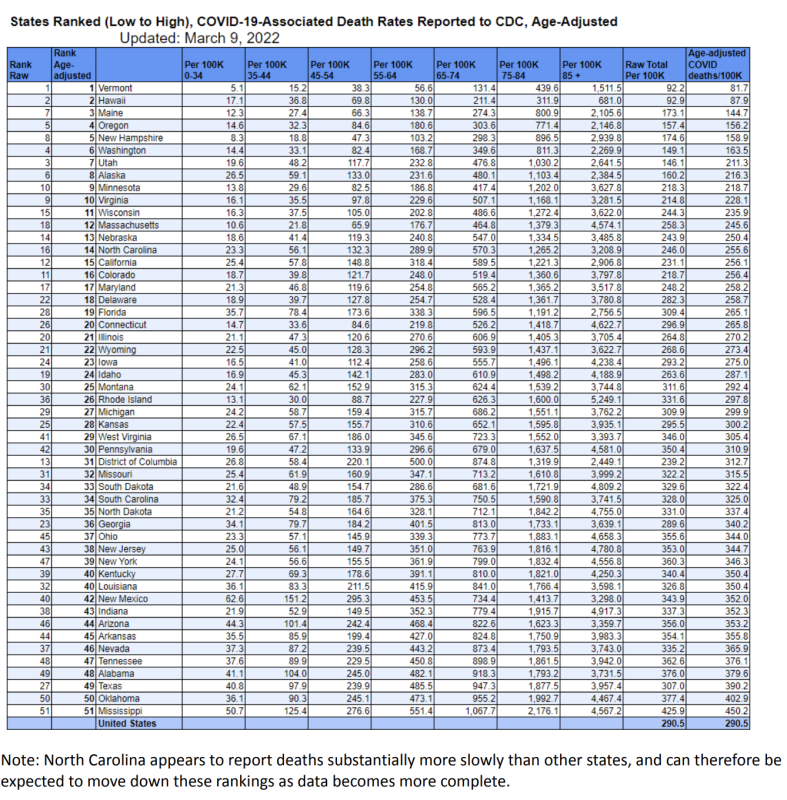

The authors aggregated and compared Covid mortality data from across the 50 states and DC and found no relationship between the stringency of lockdowns and preventing death. Furthermore, the researchers go for extra credit by controlling for population demographics. That is because vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with preexisting conditions like diabetes and obesity are significantly more vulnerable to Covid-19.

As a result, the study accounts for these confounding variables which are largely out of a state’s control. For example, Florida and Maine are two of the oldest states in the nation, making them particularly vulnerable to Covid-19, whereas states like California had some of the youngest populations. They also account for preexisting health conditions which further level the playing field when comparing pandemic response efficacy. Adjusting for these age disparities appropriately highlights the relatively low death rates in Maine and Florida and discounts states like California that also had low mortality but also younger populations.

Economic and Educational Performance

Beyond keeping death under control, a public health response must minimize collateral damage to avoid creating a whole new crisis on top of an existing one. Economic performance and preserving in-person education as much as possible are critical metrics because both are correlated with their own health outcomes.

Prolonged shocks to unemployment and growth create a slew of negative medical consequences that increase excess death. That is because contrary to the idea that one can simply label some jobs essential and others nonessential, destroying economic livelihoods often leads to human consequences such as drug abuse and depression.

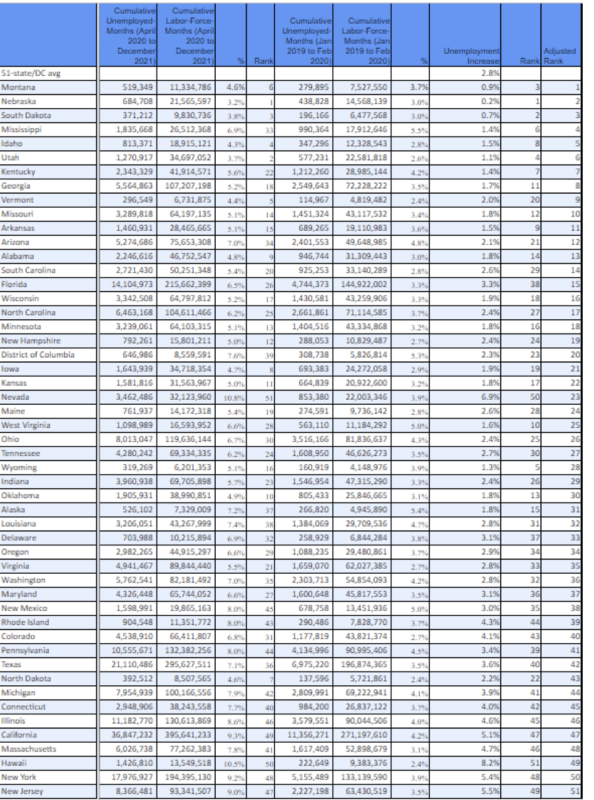

The authors measure economic performance by focusing on increases in unemployment rates and adjusting for industries like tourism and energy that are sensitive to the restrictions of other states and countries. For example, Nevada and Florida fared relatively well with the 23rd and 15th lowest unemployment increase but they would have been rated 50th and 38th without the adjustment. This correction accounts for the fact that some industries, like tourism, are almost out of the control of state policymakers, so holding local leaders accountable for unemployment in those fields would be misleading and inappropriate.

Finally, the authors correctly note that keeping children in school is also an essential component of a healthy society because if unemployment harms adults, being out of school harms the youth. The researchers point out,

One study found that school closures at the end of the previous 2019-2020 school year are associated with 13.8 million years of life lost. An NIH analysis found that life expectancy for high school graduates is 4 to 6 years longer than high school dropouts. The OECD estimates that learning losses from pandemic era school closures could cause a 3% decline in lifetime earnings, and that a loss of just one third of a year of learning has a long-term economic impact of $14 trillion.

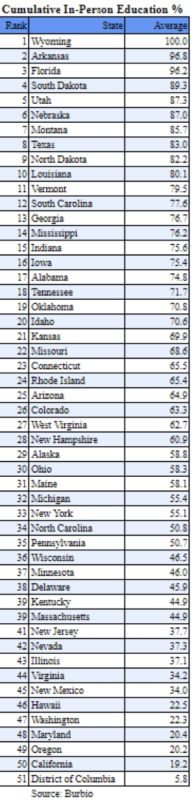

Unsurprisingly, states that had the most unemployment, typically lockdown states, also had the least amount of in-person schooling, according to the NBER paper. The authors measured educational performance based on the share of in-person schooling with half credit given for hybrid classes. The rankings for this metric feature the usual culprits: Wyoming, Arkansas, Florida at the top, California, D.C., and Oregon at the bottom.

How Do We Interpret This?

Although some report card-style studies include factors such as case counts and testing, this paper goes for the ultimate concerns of deaths, unemployment, and education.

Perhaps there are other issues to consider when evaluating a state’s response to the pandemic. However, on mitigating deaths, keeping unemployment low, and preserving in-person education, the data speaks for itself. One cannot deny that these factors measure some of the most important priorities during the pandemic.

However, we must keep in mind that using outcome-based metrics does not capture the nuances, mistakes, and achievements that comprise a state’s pandemic response. Hawaii is an easy example; to what extent is its superior performance due to its government’s response and to what extent are the outcomes due to its island geography?

The same question goes for Vermont and Maine; how does their status as rural Northeast states make their job easier or harder than a more urbanized state like New York or New Jersey? Sometimes, we just don’t know why a state did so well or so poorly, especially if all we are accounting for is Covid deaths.

Furthermore, many states may have done relatively well in the overall rankings but experienced a level of vitriol and politics that make emulating their approach questionable. For example, surely we would like to avoid a situation like Governor Whitmer of Michigan making an unconstitutional power grab or Governor DeSantis of Florida threatening local schools that disobey his executive order against masks.

Then there are the countless instances of hypocrisy, such as California’s Gavin Newsom attending a maskless dinner during the height of the pandemic or the numerous governors that chastised those who opposed their public health measures but encouraged racial justice protests. Such behavior is indicative of undesirable leadership but is not neatly included in an outcome-based study. However, no ranking can be perfect nor is it likely that one can actually encapsulate all the variables that go into a successful public health response.

The major conclusions drawn from this working paper are that lockdowns did very little if anything to help mitigate Covid-19 deaths, especially when you account for differences in demographics that give some states an advantage, and some a disadvantage.

Furthermore, the states that kept education in-person and unemployment low did so without unduly endangering their citizens. Ultimately this report card rewarded states that kept Covid deaths low but also managed to mitigate unemployment and kept schools open. Delivering on all three criteria signifies that a state did not create more of a public-health crisis on top of an existing one.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.