How much can Denmark teach us today about the natural course of the pandemic and the effects of human interventions?

A lot. But let’s start at the beginning.

Long ago, when the world was convinced that stubborn, unlocked-down Sweden was performing a deadly Covid experiment, I explored mortality statistics in the Nordic countries. My first analysis (June 2020, published in Hebrew) was titled “Lockdown and Covid mortality: refutations from Sweden.” At that time Covid mortality in Sweden was about five times higher than in Denmark.

In my second analysis of the topic (January 2021, on Twitter), I compared flu, Covid, and all-cause mortality in Denmark and Sweden. Over three consecutive “flu years” (October through September), Sweden fared better than Denmark on flu mortality (pre-pandemic), worse on Covid mortality (when flu was absent), and better or similar to Denmark on overall mortality. My analysis was based on data through September 2020.

We now have a much wider perspective on Sweden (elsewhere and below) and Denmark (below).

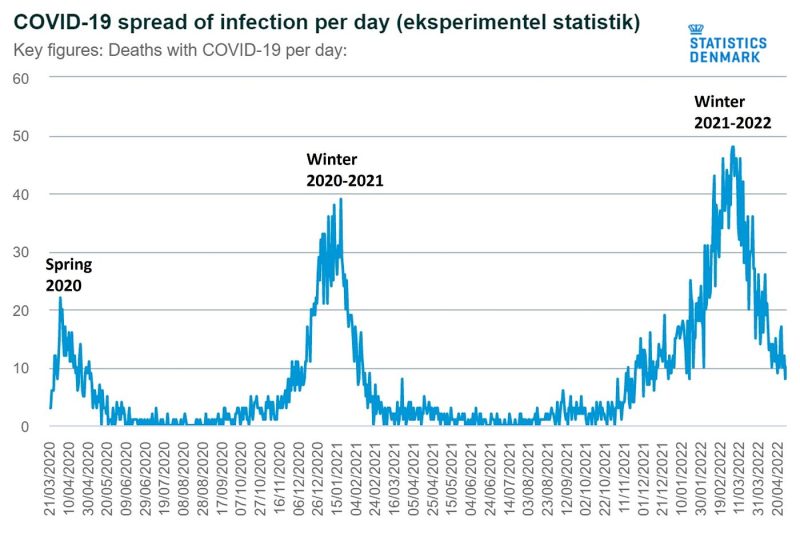

For reasons that remain unknown, the first major wave of the pandemic was not synchronized worldwide. Denmark, like many other countries, experienced only a minor wave in the Spring of 2020, which was naively attributed to lockdown measures. Time proved that it was no more than a nature-dictated delay — until the winter of 2020–2021.

What was the excess mortality in Denmark during the pandemic?

To answer the question we first need to choose carefully a baseline mortality rate — the expected rate if there were no pandemic. That’s the key number.

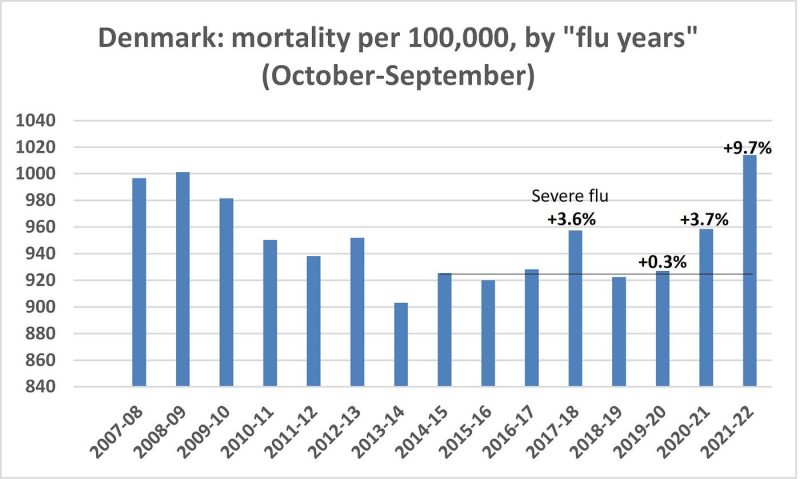

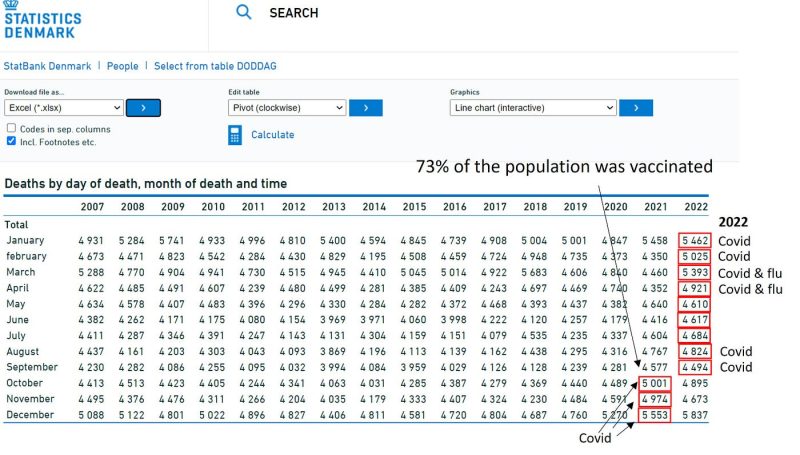

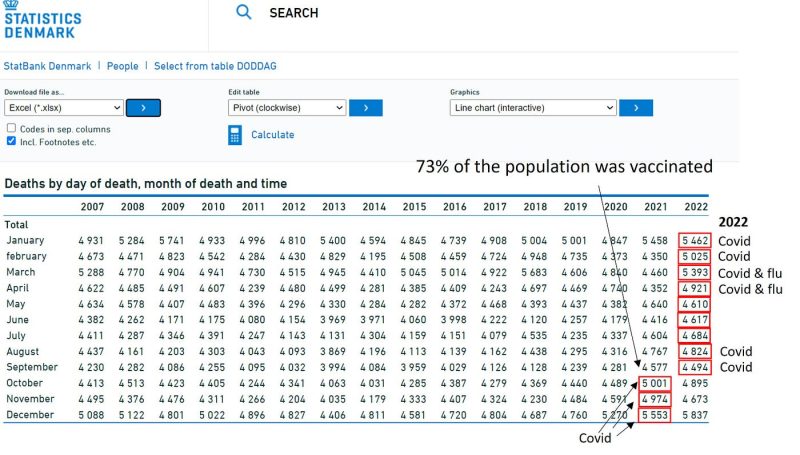

As shown in the bar graph below, all-cause mortality in Denmark generally declined between 2007 and 2014. In the following five years, up to the pre-pandemic flu year (2018–19), the rate was stable except for 2017–18, a notable exception due to a severe flu season. I used the average mortality rate in those four, fairly stable years as a baseline rate (horizonal line) for excess mortality (%).

Experiencing only a minor Covid wave in the Spring of 2020, Denmark escaped excess mortality in the first pandemic (flu) year: October 2019-September 2020.

Sweden, by contrast, was hit early on, ending the first pandemic (flu) year with excess mortality of 4 percent, part of which has “balanced” a mortality deficit of 3.5 percent in the pre-pandemic year. The true Covid toll in Sweden in the first pandemic year was probably 1–2 percent excess mortality — not 100 percent, predicted by reckless models that shut down much of the world.

In the winter of 2020–2021, several months after the pseudo-success of mitigation, Denmark succumbed to its first major Covid wave. The death toll of Covid in Denmark in the second pandemic year (October 2020-September 2021) was 3.7 percent excess mortality, similar to Sweden a year earlier (4 percent).

What happened next in Denmark is nothing short of shocking. At a time that was considered post-pandemic in many countries, excess mortality in Denmark markedly increased. Not so in Sweden.

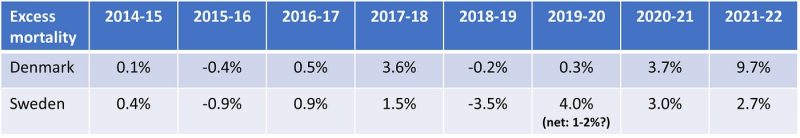

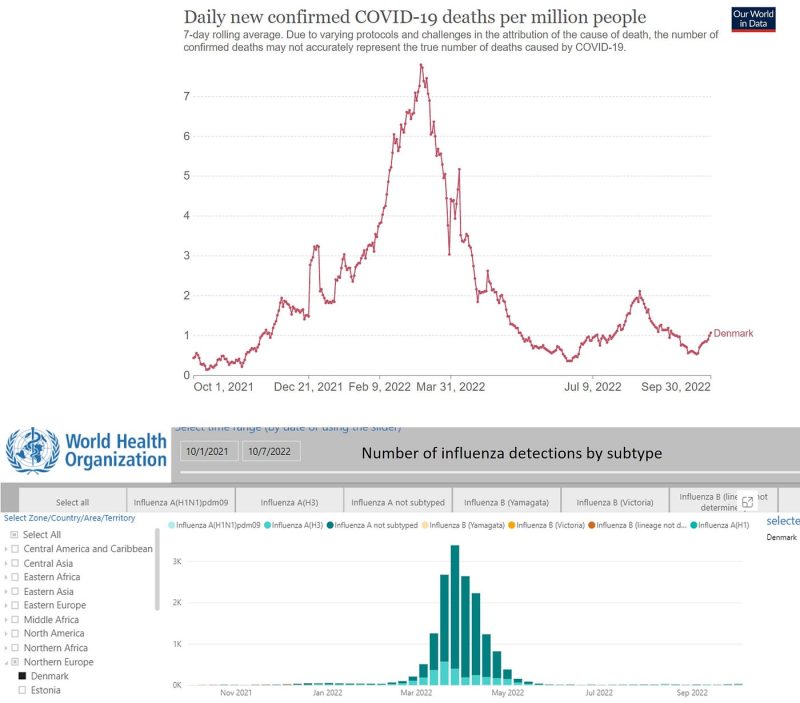

The table shows a year-by-year comparison (October through September) of excess mortality in the two countries.

First, we have no evidence that the so-called mitigation efforts had any merit in Denmark. Considering Sweden’s pre-pandemic “mortality deficit,” Denmark did not fare meaningfully better — if at all — over two years of the pandemic.

Second, matters got worse in Denmark in the past flu year. Excess mortality unexpectedly rose to 9.7 percent whereas it (modestly) declined in Sweden. In a country with over 50,000 deaths each year, 10 percent excess mortality corresponds to about 5,000 deaths above “normal.”

Which factors in Denmark, between October 2021 and September 2022, could have played a role?

There were at least three: Covid, flu, and vaccines, primarily Covid vaccines, which were highly effective, or not. We will return to the last topic shortly.

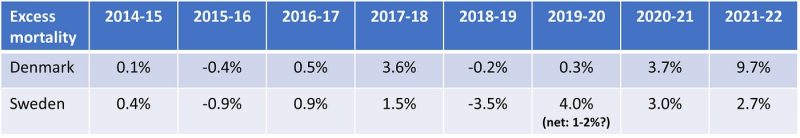

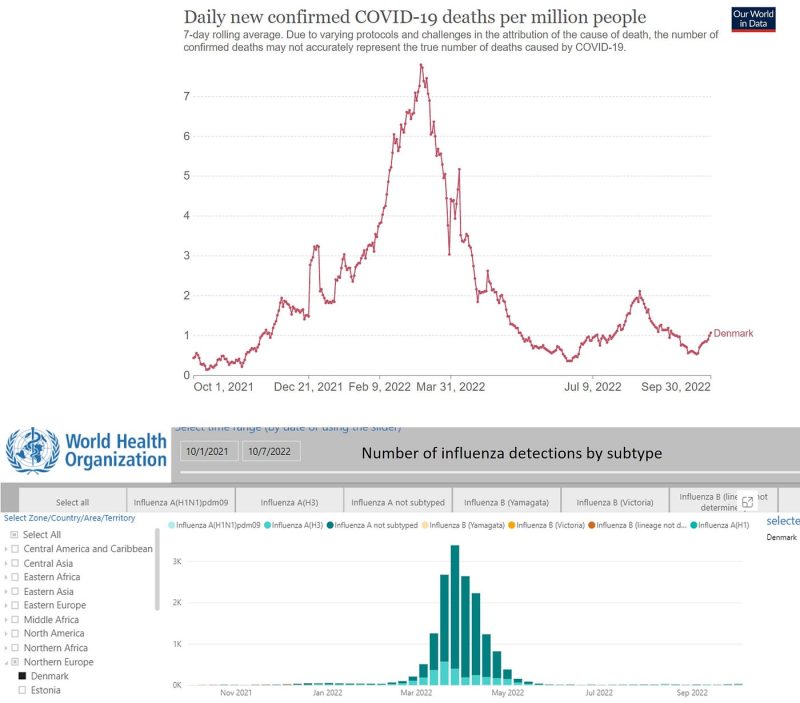

The two graphs below are limited to the past flu year. Regardless of misattribution of deaths to Covid, we observe a prolonged Covid mortality wave spanning 6–7 months, and another small and short wave.

Synchronized below, we see a wave of seasonal flu, about 2-month long, partly overlapping the major Covid mortality wave. (Flu mortality should be somewhat shifted to the right.) That was the first significant reappearance of the flu in Denmark since the beginning of the pandemic.

Monthly data on all-cause mortality are well matched with these graphs (red rectangles). For each month, I indicated the corresponding wave, if present.

A month-over-month comparison of the past flu year with every year between 2014 and 2019 revealed at least 200 excess deaths each month (and often many more) in over 90 percent of the comparisons.

I previously argued that computation of Covid excess mortality should be terminated upon the return of the flu because we cannot quantify the share of the latter. I will make a semi-quantitative exception here and try to justify it.

The flu wave in Denmark was short and can account for deaths only in two to three months. It cannot account for much of the 10 percent excess mortality in the past flu year. Some excess deaths might have been due to Covid vaccines and other causes such as late effects of disrupted life. Nonetheless, most of the excess mortality in Denmark must have been Covid deaths, aligned with a major, prolonged Covid wave (6–7 months) and another minor wave (2 months).

Which brings us to the key point: vaccination.

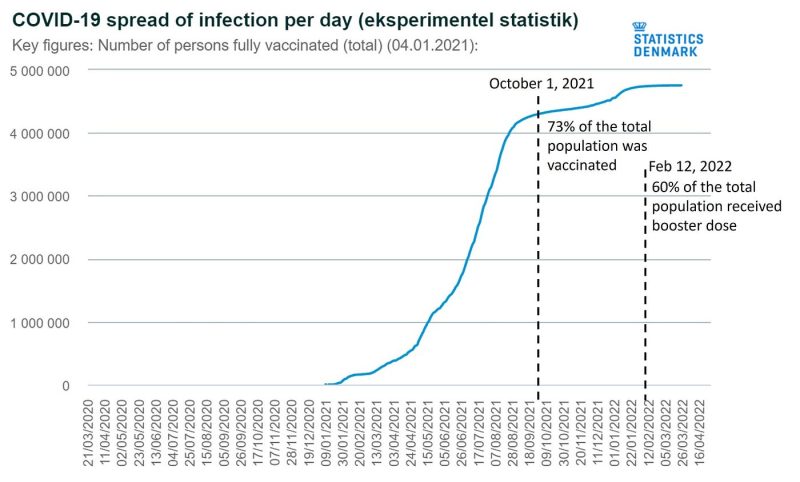

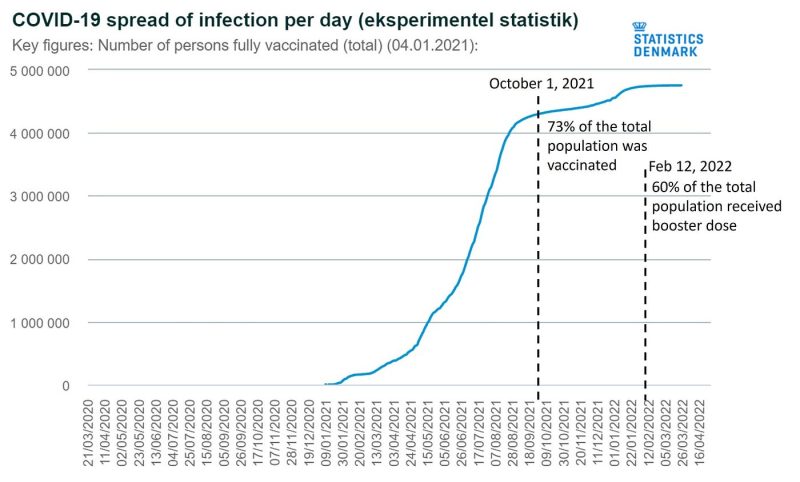

By the beginning of the past flu year, over 70 percent of the population of Denmark was fully vaccinated against Covid, and by mid-February 2022, 60 percent of the population received a booster dose. The percentages should be higher in older, vulnerable age groups.

If the vaccines were highly effective against death, why was excess mortality in Denmark so much higher than in the previous flu year? Why was it so much higher than excess mortality in Sweden in the first pandemic year — without vaccines — when the virus was much more virulent than Omicron? Unlike Sweden, there was no “mortality deficit” to account for.

Whatever the exact share of Covid deaths was, it is impossible to reconcile a highly effective vaccine with the excess mortality in Denmark in the past flu year. Is there any epidemiologist on the planet who would claim that, without vaccination, excess mortality in Denmark would have been much higher than 10 percent? Five times as high, if the vaccines were highly effective? Or even just twice as high?

A second lesson from Denmark: highly effective vaccines — they were not. Have they even been somewhat effective beyond a narrow, inconsequential, window of time?

It seems that countries should undergo at least two major mortality waves before reaching the endemic stage — regardless of the prevailing strain. Those that started late, like Denmark, Finland and Norway, will end late. Denmark teaches us that mediocre vaccines cannot change the natural course of a pandemic.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.