We are approaching the fifth anniversary of the trial that set the stage for the vaccination of billions by an experimental product — the Pfizer mRNA Covid vaccine (BNT162b2). There is no other scientific paper that affected so many within a few months of its publication.

Was it a well-designed trial? In many respects, it was not. But was it at least trustworthy as far as the main results are concerned? It is uncertain, and I am not alone in the camp of skeptics. Over the years, I have read various critiques, ranging from testimonies about poor conduct to questionable inference.

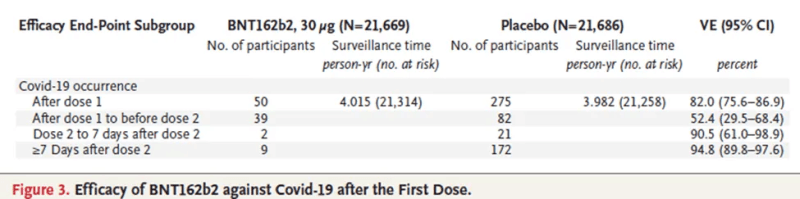

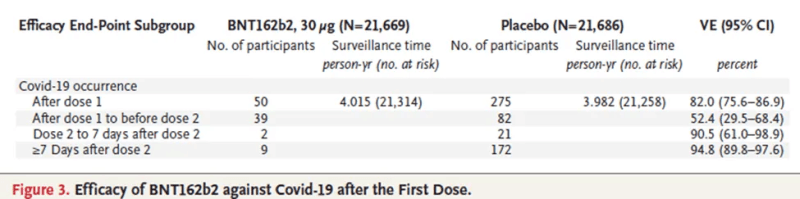

For those who are unfamiliar with the design, here is the essence. About 40,000 people were randomized to receive two doses of the Pfizer vaccine, 21 days apart, or two doses of a placebo. Descriptive statistics show well-balanced characteristics in the two arms of the study, with about 20,000 people in each. Participants reported symptoms between the first injection and the end of the follow-up. If they reported at least one of 10 Covid-like symptoms, a PCR test was conducted. If positive, the participant was classified as a Covid case on the date of the first reported symptom.

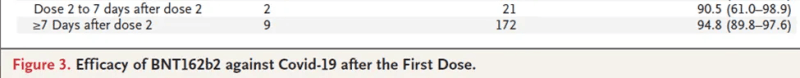

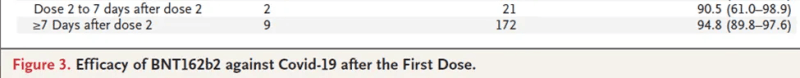

The main results are shown below.

Notice that we get the correct results from the count of events alone because the denominator (time at risk) was almost identical in the two arms. For example, (1–2/21)x100=90.5%.

My two cents on the results.

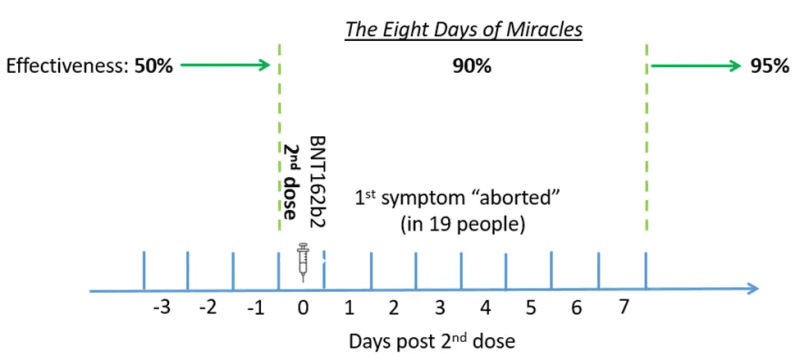

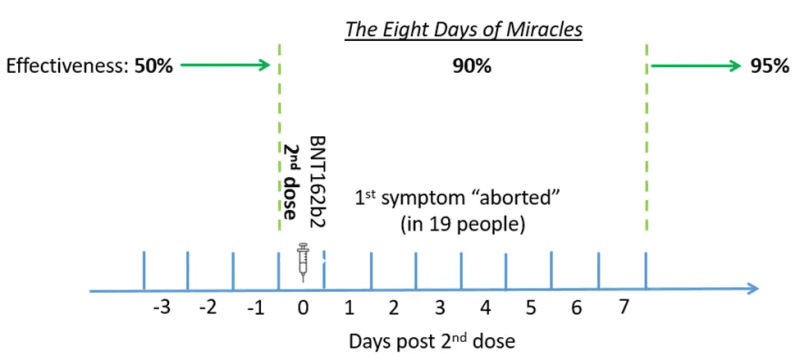

I will focus first on a narrow window — eight days in the follow-up time — shortly after the second dose. I call that period The Eight Days of Miracles because what happened at that time was miraculous. Vaccine effectiveness has dramatically increased in the blink of an eye: from 50% to 90%. Too good to be true?

If we accept that the Pfizer vaccine was highly effective in preventing symptomatic infection, we don’t need more than one week of follow-up after dose 2. Does it matter whether a risk is cut by 90% or by 95%? Not really. Of course, that’s if we trust that estimate of 90% effectiveness.

In those eight days, there were 19 more cases in placebo recipients than in vaccine recipients. All that it takes to change the effectiveness back to 50% is to find 10 more cases or so in about 20,000 recipients of the second dose. Do we have any plausible reason to assume that cases were missed in the vaccine arm of the trial (undercounting) in The Eight Days of Miracles?

We surely do.

Misattributing Covid Symptoms to Side Effects

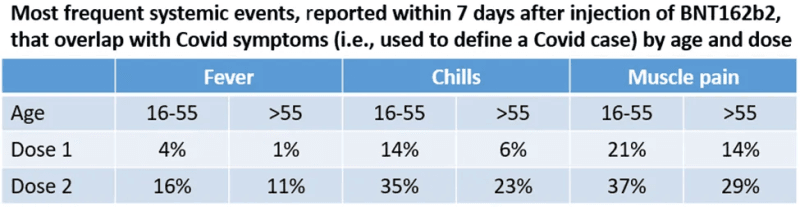

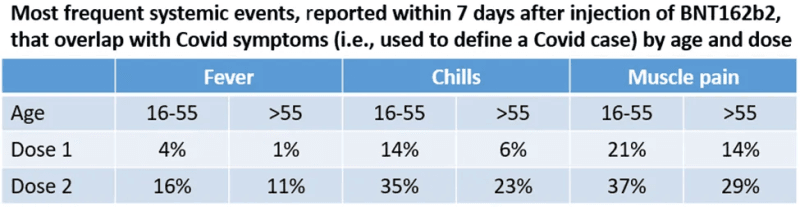

As we all know, side effects were common, and they were much more common after the second dose than after the first. The table below shows the frequency of three symptoms that were also considered as Covid symptoms in the definition of a case.

We cannot add the percentages because a participant could have reported multiple symptoms. Nonetheless, with almost 20,000 people in the vaccine arm, these percentages translate to thousands of people whose symptoms were attributed to side effects of the second dose (“reactogenicity”). For example, over 2,000 vaccine recipients reported fever after the second dose.

Was Covid ruled out by a PCR test in every case?

No, it was not.

That’s what we find in the protocol (section 8.13).

“During the 7 days following each vaccination, potential COVID-19 symptoms that overlap with specific events (ie, fever, chills, new or increased muscle pain, diarrhea, vomiting) should not trigger a potential COVID-19 illness visit unless, in the investigator’s opinion, the clinical picture is more indicative of a possible COVID-19 illness than vaccine reactogenicity.” (my italics)

In other words, a PCR test is left to the discretion of the investigator, with a clear guideline: it is a priori assumed not to be Covid. Indeed, of thousands of participants who reported such symptoms in those seven days, only a few hundred were tested and classified as “suspected but unconfirmed Covid.” All others were not tested.

How do we know how many were tested?

There is an FDA Briefing Document (Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting, December 10, 2020), which contains the following sentence:

“Suspected [but unconfirmed] COVID-19 cases that occurred within 7 days after any vaccination were 409 in the vaccine group vs. 287 in the placebo group.” (my italics)

These are the numbers of tests after both injections.

Is it likely or unlikely that this practice has missed 10 (or 20 or 30) Covid cases among thousands who were deemed to have had side effects rather than Covid during The Eight Days of Miracles?

Faster and Faster (Effectiveness)

Actually, it did not take eight days to increase effectiveness from 50% to 90%. The miracle happened over five days at most.

First, there is a typo in the effectiveness table, or a minor deception. It was a seven-day period, not eight.

The last row shows that the seventh day was included in the computation of 95% effectiveness (≥7), so the previous row should read: “Dose 2 to 6 days after dose 2.” That’s a total of seven days, including the day of the injection.

Second, a vaccine is not an aspirin for a headache. It takes time to mount an immune response and then to strike back against the offender. How much time? I would say that if I got the second dose on Monday at noon (I didn’t), and it’s the midst of the incubation period, I don’t expect the injection to abort the first symptom that would hit me on Tuesday evening. It’s too early for the vaccine to work. So, we should confidently cut at least two days from those seven days.

That leaves five days to increase effectiveness from 50% to 90%.

Could the vaccine have prevented an infection in those five days, in addition to aborting the first symptom after an infection? Well, the incubation period is about five days, so there is not much room for preventing a symptomatic infection by preventing an infection. (Theoretically, both mechanisms could have operated in the next interval, ≥7 days, but we are told that effectiveness was almost maximal by the sixth day. If the vaccine did work, it would have aborted symptoms, not prevented infections.)

Should we call that period Days of Miracles or Days of Uncertainty?

And there was another miracle in the trial…

Underreporting Non-Covid Symptoms in the Vaccine Arm

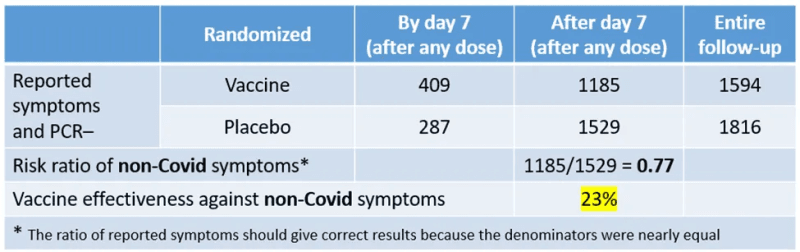

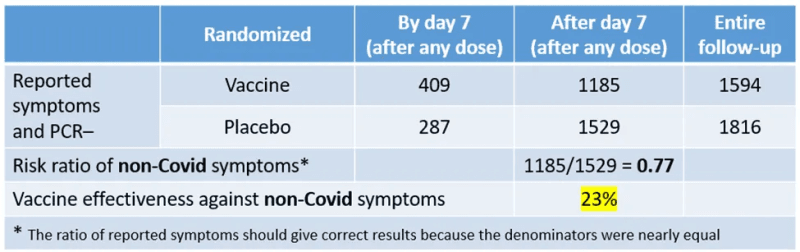

The following is an excerpt from the FDA Briefing Document (Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting, December 10, 2020). I quoted earlier one sentence from this paragraph.

“Among 3,410 total cases of suspected but unconfirmed COVID-19 in the overall study population, 1,594 occurred in the vaccine group vs. 1816 in the placebo group. Suspected COVID-19 cases that occurred within 7 days after any vaccination were 409 in the vaccine group vs. 287 in the placebo group. It is possible that the imbalance in suspected COVID-19 cases occurring in the 7 days postvaccination represents vaccine reactogenicity with symptoms that overlap with those of COVID-19.” (my italics)

This text should have been included in the published paper or in the supplementary appendix. Instead, it was buried in a 53-page-long FDA document.

My table below transcribes the numbers from the text. I added the number of cases of non-Covid symptoms that were reported outside the one-week post-injection window. Simple subtraction.

In the first week post any injection, vaccine recipients were more likely to report non-Covid symptoms because some side effects (“reactogenicity”) were similar to Covid symptoms (e.g., fever). We have already discussed this topic.

But the disturbing result shows up outside the reactogenicity window. In most of the follow-up time, vaccine recipients were less likely to report non-Covid symptoms (risk ratio of 0.77). Why? Why do participants in the two arms of a well-balanced trial report non-Covid, yet Covid-like, symptoms at a different rate? Does the Pfizer vaccine protect against symptoms that are not caused by the virus (“vaccine effectiveness” of 23%)? Another miracle?

Whatever the explanation might be, nothing can reassure us that endpoint ascertainment was uniformly executed for the two arms of the trial. And differential ascertainment of the outcome is a big red flag for any trial.

Moreover, if non-Covid symptoms were underreported by vaccine recipients as compared with placebo recipients, Covid symptoms have also been underreported at that time. In a blinded trial, participants have no way of guessing what has caused their symptoms: the virus or something else. Vaccine recipients could not have “decided” to underreport only a sore throat that was not Covid. Or was it another miracle?

The implication is obvious: regardless of any effect of the vaccine, the number of cases was undercounted in vaccine recipients between 7 days after the first dose and the second dose, and 7 or more days after the second dose. Unfortunately, we cannot tell how the numbers are split between the two periods. Nor can we tell whether it was indeed underreporting or undertesting or anything else along the data trail.

Have the authors of the FDA document missed the trivial computation above? Unlikely. So why did they explain overreporting during one week post-injection and remain silent about underreporting during most of the follow-up? Your guess is as good as mine.

How much faith should we still have in that trial?

Is it surprising that no miracle was observed in Israel, “the Pfizer laboratory,” shortly after the trial?

Republished from Medium

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.