Life in the shadow of an active volcano is a sobering experience. A stratovolcano like Popocatépetl — which means “smoking mountain” in Nahuatl — marks the landscape as an ever-present reminder of nature’s immense and thunderous power. A volcano is a beautiful, but severely imposing, memento mori.

Popocatépetl — nicknamed “El Popo,” or “Don Goyo” by locals — lives on the eastern half of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, locked in an embrace with his volcanic twin, the long-dormant Iztaccíhuatl (“the white lady”). Rising to a height of 17,802 feet, he (and yes, to us he is a living being) is the second-highest peak in Mexico; over 25 million people surround him in the states of Puebla, Tlaxcala, Morelos, Mexico State, and Mexico City.

Since he awakened from slumber in 1994, El Popo has lived up to his name. A gentle stream of smoke wafts up from his crater almost daily, an oddly comforting sign that the earth is warm with movement. Native Mexicans and foreigners alike see the volcano as a dual force, both beautiful and potentially destructive, and alive with symbolism.

A rich mythology surrounding the volcano helps people to conceptualize their relationship to the powerful forces in their environment that lie outside of their control. While Popo represents a constant reminder of death, none of the myths about him portray him simply as a “danger.” He is far from a villain or an angry spirit; if anything, he is typically a powerful, yet benevolent presence. El Popo is a “cuate” (or “buddy”), a guardian, a warrior, and a symbol of love and loyalty.

A few days ago, he began erupting.

My purpose in this brief study is to examine myth-making processes in the face of crisis or natural disaster. Like a virus, a volcano is a powerful natural phenomenon that man cannot domesticate. We may be able to prepare for its effects and predict its rumblings, but to some extent, those who live near a volcano must come to terms with its destructive power over their existence.

Myth and narrative allow us to locate this inevitable danger within a nuanced tapestry of experience that encompasses the totality of life. This tapestry weaves us into the environment we occupy, in a harmonic way, rather than separating us from its darknesses. It allows us to see the world through a textured and poetic lens, holistic and rooted in love. It helps us to overcome fear, and prioritize our values.

Ideally, access to scientific data should enrich these myths, increasing the resolution with which we view our lives. We may not be able to control the natural forces in our environment, but understanding how they work can help us navigate our relationships with them more skillfully.

But all too often, scientific “experts” end up reducing the resolution with which we view reality instead. Increased data leads, sadly, to tunnel vision, magnifying the perceived salience of threats and cropping out the beauty and nuance of myth. Inflamed by hubris, they imagine we should use our knowledge not to enrich our relationship with the natural world, but to manage and control it.

Even worse, these “experts” tend to see themselves as enlightened and attempt to impose their simplistic worldview on others. Many of the peoples they evangelize not only have different priorities, but also hundreds of years of practical experience navigating the environment in which they live.

Here I will briefly examine four myths created by the various peoples who live in the shadow of Popocatépetl (one prehispanic traditional, one postcolonial traditional, one modern and urban, and one created by a foreigner). These myths seem to provide protection against the simplistic, heavily-cropped, fear-based narratives that are pushed on us from outside.

It is clear that the more ancient and culturally rooted these myths are, the stronger they tend to be; but it’s interesting to note that even foreigners can create their own myths that integrate them effectively into these tapestries of meaning.

Above all, I hope these examples can provide inspiration for us as we confront a similar predicament from different cultural perspectives. Some of us may have deep roots in religious or spiritual traditions, or physical communities that go back centuries; others may have little to no sense of rooted mythological tradition.

Either way, it is possible for us to engage in the process of myth-making, to weave ourselves into beautiful tapestries that encompass the totality of existence and highlight our true priorities, and in this way, to counter the onslaught of the simplistic imperialist “experts” who aim to dictate our lives.

“Expert” Imperial Narratives: More Data, Less Nuance

For the past couple of months, El Popo has been spewing more ash than normal. But this past week, there have been several minor eruptions.

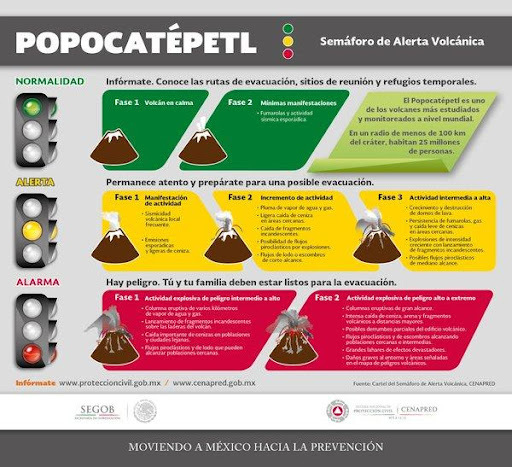

On Saturday, May 20, Benito Juarez International, one of the most heavily-trafficked airports in North America, was forced to close for more than five hours due to volcanic ashfall. More than 100 flights have been delayed or canceled, and the Ministry of National Defense deployed over 7,000 troops to assist residents near the volcano in case of evacuation. On Sunday, May 21, CENAPRED raised the traffic light alert system (similar to that used during Covid) from “Yellow Phase 2” to “Yellow Phase 3,” the highest level before Red.

The volcano is highly surveilled. There are six cameras and a thermal imaging device positioned around the crater, twelve 24-hour seismological monitoring stations, and 13 scientists keep eternal watch over this incoming data stream from a central command center in Mexico City. The scientists watch for ash clouds, check the motion of seismographs, record wind patterns, and monitor gases around the peak or in nearby springs.

“How do you explain all of this to 25 million non-experts living within a 62-mile (100-kilometer) radius who have grown so used to living near the volcano?” asks María Verza in an Associated Press report. “Authorities came up with the simple idea of a volcano ‘stoplight’ with three colors: green for safety, yellow for alert and red for danger.”

A “simple idea” indeed. The traffic light system supports exactly three shades of nuance, whose main distinction, as far as I can tell, seems to be the level of fear we are requested to maintain. For all their technical sophistication and their 24-hour, panoramic data streams, the message of the authorities and “experts” boils down to something almost insultingly childish and profane: a monolithic petition to fear.

You might be forgiven for thinking that the purpose of data collection is to achieve mastery over fear. Knowledge is power, as they say; so, if we know more, shouldn’t we fear less? The “experts” could provide the people with data, increasing the resolution with which they view their environment; but instead, they reduce that resolution by distilling their knowledge to a single-minded message of danger.

The volcano becomes a symbol of peril, and nothing more; gone is his beauty, his cultural significance; gone is the somber mystery of life. Don Goyo — indisputably a he — becomes merely an “it:” no longer a friend, but a threatening Other.

Next to the textured, poetic mentality of the people who live alongside the volcano, this ostensibly enlightened message comes across as crude and unsophisticated. But the media has difficulty understanding why their simplistic ideas can’t get through to their obviously ignorant audience.

NMás reports: [note: this video may be geoblocked outside of Mexico, try a VPN or proxy]

“Despite the intense activity sustained by Popocatépetl, and the large quantity of ash that has fallen on the communities surrounding the volcano, the inhabitants of Santiago Xalitzintla continue going about their activities as usual, because they say they are accustomed to it. The townspeople are out in the streets, the shops and marketplaces remain open, and many people are working in the fields or out in the open air. The only difference is that in-person classes are suspended […] The volcanic activity has not done much to alter life in the communities who live near the colossus. And the majority of the people ignore the recommendations of the health authorities to avoid going outside and to wear face masks.”

Santiago Xalitzintla is the closest settlement to the volcano, located a mere eight miles from the crater.

Toña Marina Chachi, a lifetime resident of Santiago Xalitzintla who is 63 years old, has already had to evacuate in the past. An eruption in 1994 produced a rain of ash that drove her and her family from their home. After recounting this tale, she told Almanaque, “We’re accustomed to him. We’re not afraid anymore, because we already lived through it.”

Public health measures imposed on 40 neighboring municipalities look very similar to the Covid restrictions. They include park closures, distance learning, a ban on outdoor events, military checkpoints to keep out visitors and tourists, and the recommended use of face masks and goggles.

But many residents are going about their lives as normal.

“Well, of course,” resident Cruz Chalchi tells NMás. “Where would we go? As long as we’re here in town, we have to work. We have to go out. How are we going to make a living?”

Meanwhile, César Castro, laughing, confesses he decided to leave his house to wash his car. Rosa Sevilla insists that when the ash falls, they don’t get sick because they’re already used to it. Rogelio Pérez says he just doesn’t like to wear a face mask or goggles, even though his eyes sometimes burn.

Canal 13 Puebla, in a video entitled Inhabitants of Xalitzintla, avoid using face masks, despite the ashfall from Popo, interviews some of “the few inhabitants who decided to go back to using face masks.” These model citizens extol the benefits of face masks for safety and encourage others to follow the recommendations of the authorities.

“If it’s for our own good, it’s great that we should keep using face masks,” says Inés Salazar.

“How might face masks help you?” asks presenter Monserrat Navedo, in a tone uncomfortably reminiscent of a kindergarten teacher.

“I would say, for breathing,” answers Salazar. “Because the volcanic ash causes damage, and with the face masks, I think it would be a little less.”

It is not that the residents reject all help from the government, or make senselessly reckless decisions; most of them evacuate during an eruption, although some do decide to stay with their farms and take care of their animals. The government maintains evacuation routes and provides support to threatened municipalities; they distribute protective gear, food and supplies, which the people readily accept.

But in the end, each person makes their own decision about how they want to handle the crisis. They and their ancestors have been living in the shadow of Don Goyo for thousands of years. The media and the authorities are puzzled as to why they do not act with a sense of single-minded urgency; but in reality, that lack of fear belies a deep understanding of what life near a volcano actually entails. The “experts” may have their facts and data, but it is no replacement for wisdom.

I asked myself what might have allowed the residents of towns like Santiago Xalitzintla to maintain such clarity in the face of outside pressure to oversimplify reality.

Moreover, why did many of these same people — people who live in the shadow of the volcano, who maintain such an impressively stoic attitude in the face of death — fall so readily for the Covid propaganda?

I came to the conclusion that it is these strong and richly textured mythologies that have the power to keep people grounded in the face of external influence. These mythologies, which are rooted in love instead of fear, present the world as a holistic environment that is a part of us — not separate — and that contains both creative and destructive energies.

Danger is not something that emanates primarily from a threatening “Other” that must be dominated; instead, it is a natural part of life that offers us valuable lessons, strengthens us, reveals to us the truth, or perhaps can even be used to our advantage.

Many of the myths surrounding Popocatépetl go back hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, and form a deep part of the cultural identity of the peoples who tell them. But it is also clear that — while helpful — such a rich communal inheritance is not ultimately necessary. Foreigners and Mexicans from the city — who do not grow up steeped in this terroir — can also construct powerful and even influential mythologies that enter the collective consciousness.

In every case, these myths acknowledge the destructive power of the volcano. They do not erase or deny the existence of danger. Rather, danger represents merely one shade on a broad spectrum of possibilities and experiences, which ultimately neutralizes fear. In that sense, the resulting worldview is more inclusive and complex than the alarmist message of the “experts.”

Myth-Making in the Shadow of the Colossus

Popocatépetl has a special place in the hearts of all who live near him. But he is particularly special to the people of Santiago Xalitzintla. They are the ones who nicknamed him “Don Goyo,” a shorthand for the name “Gregorio.”

According to this postcolonial legend, an old man named “Gregorio Chino Popocatépetl” appeared in the foothills of the mountain to a Xalitzintla resident named Antonio. He told Antonio that he was the personified spirit of Popo, and that he would come to warn him and his descendants before an eruption, to give people time to escape.

Because of that, the people of Xalitzintla trust in the volcano. They see themselves as intimately connected to him, and under his protection. Every year on March 12, they even celebrate his birthday, “dressing him” in a suit, bringing him flowers and offerings and singing him birthday songs.

They, more than anyone, have something to fear from the volcano. But resident Francisca de los Santos says she couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. She and her neighbors joke about sending Popo more offerings in the hopes he’ll decide to quiet down.

The people of Santiago Xalitzintla treat the volcano, not as a dangerous Other, but as a family member, a guardian, and an object of love. Even as they suffer from the effects of ashfall, they display pride in their home, and look on the volcano with affection.

The great prehispanic kingdoms that surrounded Popo — most notably, the Aztecs and the Tlaxcaltecas — also personified the volcano and revered him in their mythology. The most famous myth about Popocatépetl is the tragic love story between the twin volcanoes, Popo and Iztaccíhuatl, which resembles Romeo and Juliet. This myth — one of the most iconic symbols of Mexican culture — can be found painted on the walls of Mexican restaurants on both sides of the border.

Iztaccíhuatl — who has lain lifeless since the Holocene — was a princess in one of the two great kingdoms (depending on who you talk to). Popocatépetl, her lover, was a warrior in her father’s army. Popo asked his ruler for his daughter’s hand in marriage. The king, who was waging a war against the opposing kingdom, said he would gladly give it, if only Popo returned victorious from battle.

The brave warrior Popocatépetl readily accepted. But while he was gone, a jealous rival told Iztaccíhuatl that her lover had been slain. Crushed by sadness, the princess died of a broken heart.

When Popocatépetl returned, he laid her body atop a mountain, and set to watch over her eternal sleep, where he remains to this day, a smoking torch in hand.

Far from conceptualizing the volcano as a fearsome danger, this myth portrays Popo as a venerable and complex human being. As a warrior, he is powerful and undoubtedly dangerous; but in the end, he fights for the side of the kingdom that tells the story. And above all, he is a romantic figure, motivated by love, who pays loyal homage to his lost bride.

Popo is a symbol of love, loyalty and strength, and he is identified with all the best attributes of the people who mythologize him; he is a valuable member of his community, rather than a threatening outsider.

These ancient myths are deeply rooted in the psyche of the peoples who, for generations, have lived in the mountains and valleys of Central Mexico. But Mexicans who hail from more urban environments, and may be less in touch with ancient cultural traditions, also create their own, modern myths. These myths may have fewer roots in the collective cultural consciousness, but for all that, they are no less powerful.

Eduardo V. Ríos, a photographer, filmmaker and musician from Mexico City, weaves the volcano into a stunning audiovisual narrative in his short time-lapse film Los Dos Terremotos (“The Two Earthquakes”). Filmed shortly after both the devastating 2017 earthquake and the death of his father, Los Dos Terremotos explores the idea that the tectonic shifts in our environment mirror the human stories at the center of our lives.

We are locked in a dance with the Earth, and whatever happens to her happens to us as well; Ríos asks, in two of the thirteen lines of text that make up the film’s sole narration:

“The Earth makes us tremble. Or is it we who cause her to tremble with our way of thinking?

The first earthquake lasts an instant, but the second is here to stay.”

Ríos composed the music that accompanies the breathtaking natural landscapes that whirl before our eyes; in this way, he “dances” with the volcano. While the earth’s tectonic shifts certainly bring about tragedy and pain, they remain inescapably beautiful; and above all, that pain is a helpful source of insight into our own minds, and our relationships with both our environment and each other.

Ríos elevates a simplistic narrative of catastrophe to a more sophisticated level. He weaves himself and the story of his own family into the story of a city collectively affected by a disastrous earthquake; and this, in turn, he weaves into the story of the volcano, and the motion of the world. Through his eyes we are all connected; tragedy becomes an opportunity to transform ourselves, and to communicate with something sacred, beautiful and timeless that exists beyond — but that is still a part of — ourselves.

But it’s important to recognize that the process of myth-making cannot be confined to any particular cultural group. We do not need to be immersed in a specific cultural tradition all our lives in order to benefit from its power. All of us have equal access to this ability, and no one has a monopoly on the right to engage in it.

So it was that English writer Malcolm Lowry wrote Under the Volcano, one of the most iconic modern myths about Popocatépetl, and one beloved by both the English-speaking world and Mexicans alike. Though written in the English language by a foreigner, Under the Volcano has become a strong part of Central Mexican collective consciousness; it can be found in almost any bookstore in the vicinity of Cuernavaca, where the novel takes place.

A sort of tragic visionary, Lowry — who struggled with alcoholism all his life until his “death by misadventure” in 1957 — wrote prolifically but only published two novels in his lifetime. Under the Volcano was supposed to embody the “infernal” episode in a trilogy inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Ironically, the manuscript was the only one rescued from a fire that destroyed many of his other works-in-progress.

The novel — a unique and immersive literary masterpiece laden with symbolism — went out of print a few years after it was published, but enjoyed a resurgence in popularity decades after his death. In 2005, TIME magazine listed it as one of their Top 100 English-language Novels published since 1923.

Like the other myths about Popo, Under the Volcano weaves its author’s personal struggles into the social and environmental tapestry of the world around him. The novel takes place in a single day on the Day of the Dead in 1939; its main character, based on the author himself, is a British Consul who struggles through the hell of alcoholism and a failing marriage; in the background, the beautiful volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl look on from various twisting vistas.

The volcanoes themselves, while symbolic of fire and hell, are portrayed as poetic and benevolent figures; they represent the perfect marriage, a happiness within view but forever, tragically, out of reach.

As the Consul’s life spirals into destruction, and the political world from which he is fleeing steadily loses its love of liberty, the beautiful flora, fauna, culture, and landscapes of Mexico call through the inferno of the human mind. The result, though intense, is nuanced: heaven and hell coexist in the same world; beauty and tragedy are locked in an eternal dance from which there is no escape.

This world, which bears eerie similarities to our own, is a world that “trampled down the truth and drunkards alike,” in which “tragedy was in the process of becoming unreal and meaningless,” but where “it seemed one was still permitted to remember the days when an individual life held some value and was not merely a misprint in a communiqué.”

And yet, despite that, Lowry writes: “Love is the only thing which gives meaning to our poor ways on Earth.” This is not a narrative of total despair. Somehow, poetry, love and symbolism help us to accept the full range of human experience, and to pave a measured, middle path between its many violent extremes.

Bringing Don Goyo Home: Building Our Own Personal Toolkits

What can we learn from these stories about the process of myth-making during crisis? Can we learn how to construct our own myths that protect us and insulate us from simplistic narratives of fear? And if we can, is it perhaps possible to share these myths with others, so that our broader communities can remain grounded in the face of external pressure to conform?

I believe, based on my analysis above, that it is possible — and that, moreover, it is possible to create new myths that are resilient and powerful, even in the absence of a strong pre-existing cultural tradition.

Collective consciousness, especially when it spans multiple centuries, carries immense power; but many of us have lost our communal ties and our sense of history. We may have forgotten who our ancestors were and where they came from; we may know little about what they ate, what they believed in, and the rituals they practiced.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t benefit from myth-making, ritual and tradition. If we don’t have existing traditions to draw on, we can simply create our own.

Below, I’ve isolated three of the characteristics common to all of the myths discussed above. I believe these core elements can be used to build strong mythological tapestries, keeping the people who use them insulated from outside propaganda and influence.

This may become useful as censorship increases: when facts and data cannot be disseminated effectively, it becomes harder to discern reality; in this scenario more poetic, universal truths can act as a compass to help us recognize and steer clear of lies.

Elements of Strong Myths

1. Integration

Strong myths transcend the us-vs-them mentality, dissolving the boundary between self and other. They integrate the individual into the fabric of a world beyond themselves. The individual and their environment become symbolic mirrors of each other, engaged in a harmonic dance.

Within this mirror, the individual can find their own values and priorities reflected back at them — but at the same time, challenges and threats present themselves as opportunities for transformation. Danger, then, is not a foreign element to be suppressed or eliminated; rather, it is an invitation to reflect on our relationship with forces more powerful than ourselves.

2. Holistic Vision

Strong myths find a place for the entire range of human emotions and experiences. Rather than denying that which makes us uncomfortable or afraid, they invite us to explore difficult concepts or themes. They may present these topics playfully, artfully, or with somber reverence; but whatever their approach, they add textured sophistication to our understanding of life.

Nuance replaces simplicity, and stereotypes fall away in the face of practical, day-to-day experience and wisdom. Strong myths give us a holistic perspective on reality; they show us that things are not always what they seem, that the world is full of contradictions and paradoxes, and that there is seldom only one “correct” way forward. Instead of dictating to us how we should engage with our environment, they give us the tools to anchor our own priorities and values within a complex palette of conceivable possibilities.

3. Love, Beauty and Imagination Conquer Fear

Perhaps most importantly, strong myths elevate love and vanquish fear. They find beauty even in the face of the most unfathomable darkness; they extend mercy even to the condemned. Fear has a tendency to oversimplify reality, to narrow the mind and to choke imagination; all these things make us vulnerable to manipulation.

Strong myths, by contrast, do none of these things. They use love and imagination to explore new possibilities, send out tendrils and create a more beautiful world. Fear does not take over the creative palette; it is merely one shade among many other, far more interesting pigments.

Love keeps us interested in our relationship with the world around us, and imagination helps us to consistently seek out new ways of engaging with it. Ultimately this empowers us to contribute to making that world a better place. By contrast, fear shuts down experimentation, punishes creativity, and disregards beauty as superfluous.

Can we use these mythological blueprints to build resilient communities like the one in Santiago Xalitzintla? What might our post-Covid myths, murals, stories, songs, films, novels, poetry, and rituals look like? Artistic mastery helps bring mythologies vividly to life, but we don’t necessarily need to be accomplished professionals to participate in the process of myth-making.

Even simple rituals, prayers, songs, poems, offerings, or sketches can contribute something valuable to the collective consciousness. And above all, they give us personal strength and help us to stay grounded. If we can create them for ourselves, it’s better than nothing; but if we can share them with anyone else, they become that much more powerful.

Crisis myth-making may perform a function similar to the samurai-inspired “fear meditation” proposed by Alan Lash. By humanizing our fears and exploring them through myth, imagination, and ritual, we can acquaint ourselves with their implications and figure out how best to relate to and learn from them.

Myth acts as a kind of psychic preparation for situations outside of our control; it reminds us of what is important, connects us with those we care about and playfully or poetically reframes our own fragility and mortality. It gives us perspective on life, and elevates us from the terrestrial realm of data to the empyreal palaces of wisdom.

Here’s a challenge: have fun. Take these blueprints, play around, and try making some myths of your own.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.