The following is an excerpt from Dr. Julie Ponesse’s book, Our Last Innocent Moment.

Be this the whetstone of your sword. Let grief

Convert to anger. Blunt not the heart; enrage it.

—Shakespeare, MacBeth

I don’t know if you’ve noticed but people these days are angry.

Angry at those who embrace the COVID narrative and those who resist it; angry at politicians for doing whatever it takes to stay in power; angry at public health officials who, instead of showing some humility over the failures of the last three years, maintain that we ought to have masked more and locked down harder; angry at loved ones who continue to betray us or, maybe worst of all, pretend they never did.

And COVID isn’t the only source of our anger. It targets those who fly Ukrainian flags (or don’t), drive electric vehicles (or won’t), and move into 15-minute cities (or out of them). Even venturing to the grocery store is an act of bravery where people seem to be looking for a reason to ram their cart into the heels of the person in front of them.

Much of this anger isn’t run-of-the-mill indignation. There’s an enthusiasm to it. It’s a high-impact, visceral kind of disgust bordering on Shakespeare’s “tiger-footed rage.” And it seems to be less a response to what one does or says than to who one is, a revulsion at another’s very being. During the intensity of the COVID crisis, I frequently heard “I can’t stand that sort of person,” or “Just looking at her makes me furious.”

Anger has become such a cultural phenomenon that a Canadian research consulting firm recently launched a “Rage Index,” rating our mood about everything from gas prices to rezoning parts of Ontario’s Greenbelt. You would think that, coming out of a global crisis, people would feel relieved or even euphoric that it had finally ended. Instead, we seem to be quite happily setting up camp in the untamed wilderness of our more tribal emotions.

Whatever its source, I’m not sure most of us are even aware of how angry we are or what we are angry about, beyond an amorphous weightiness lurking in the background of our daily movements. I sometimes catch myself with a tightened jaw or clenched fist without an obvious cause. The last time I bought bread at our local bakery, the tension was palpable. Bags of sourdough thumped on the counter, angry fingers assaulting the debit machine, doors slamming, voices raised, fur bristled. Why?

Where is all this rage coming from? Are there more reasons to be angry these days? Or is anger just more culturally accepted, or expected? Is it part of being progressive? (If you don’t berate the outliers, are you even civilized?) Or have we reached an unexpected and perilous moment of emotional unraveling? And, if so, what (or who) pulled the initial thread?

When I was in graduate school, I read a paper about anger that stopped me in my tracks: “On the Reasons to be Angry Forever.” Its author, University of Chicago philosopher Agnes Callard, argues that there are not only reasons to get angry but reasons to remain angry, and they are exactly the same reasons we had for getting angry in the first place. Callard describes what she calls “pure anger,” a response to the perceived gap between “the way the world is and the way it ought to be.”

Anger can be a way of taking up the gauntlet, she says, a purposeful form of moral protest aimed at restoring the moral order. It can motivate people to lobby, to vote differently, to stand by unpopular opinions, even to engage in acts of civil disobedience. Joan of Arc’s anger inspired her to lead a whole army. Malcolm X said only anger, not tears, can bring political change. And so I wonder, is there a morally pure form of anger that could help us to restore the moral order? Now that we seem to have fallen off the moral ‘wagon,’ could anger be a way to help us climb back on?

The Fifth Circle of Hell

COVID anger, or “pandemic rage,” is hardly a novel topic. Statisticians are tracking it, journalists are exploring its cultural significance, and psychologists, who largely agree that anger is a ‘red-flag’ alert to a threatening environment, focus on managing anger so it doesn’t consume us. (Though the meditation and deep breathing they recommend strike me as weak antidotes to our ire.) Evolutionary biologists say anger has been preserved in us because it is useful, alerting us to interpersonal conflicts of interest so we can bargain more effectively. And psychiatrists typically see anger as a secondary emotion, a response to our fears and anxieties, rather than to a situation itself.

When I am perplexed by something, my classical roots draw me first to the ancients, to see how humans first started to think about it. There, we find two interesting ideas about anger.

One is a close association between anger and madness, a cautionary tale of sorts. The Stoic philosopher Seneca described anger as a temporary madness, likening it to a collapsing building that’s reduced to rubble even as it crushes what it falls upon. The other is that anger is a visceral experience, accompanied by changes in the body. The 5th century BC physician Hippocrates’ recommendation “to vent your spleen” reflects the ancient idea that there is a physiology to anger — that it changes, or is changed by, the body — an idea that persisted at least until Charles Darwin who claimed that, “without slight flush, acceleration of pulse, or rigidity of muscles – man cannot be said to be angry.”

Aristotle took a more calculated view of anger, describing it as a compelling means of persuasion. Anger, he says, is an awakening of the spirited part of the soul, which can be aroused (by orators and playwrights, for example) simply by tapping into the feeling of having been slighted.

Martha Nussbaum elaborates on Aristotle’s idea, describing anger as a symptom of ego fragility, a subconscious way to assert power in a world that feels so beyond our control. She says anger involves a “status-injury” or “down-ranking.” We anger when we feel that our social position is threatened. We anger at the offender’s relative social elevation. We anger at being made a victim. We may even anger as a “Hail Mary” attempt to vindicate ourselves in a world that tries to destroy us.

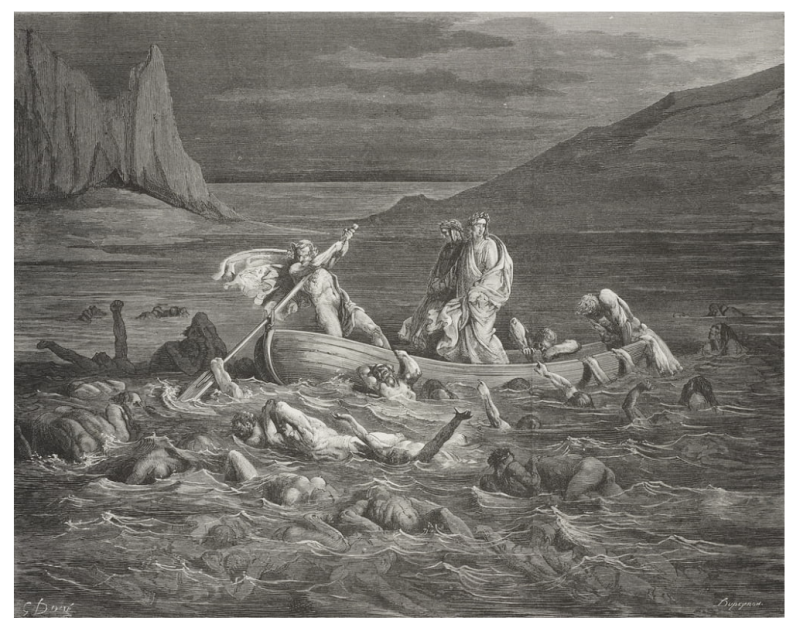

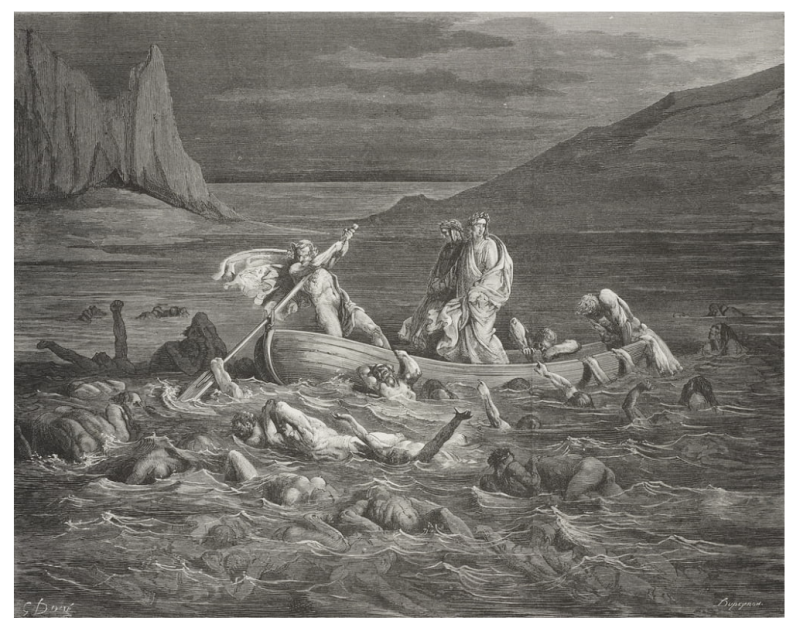

Perhaps the most well-known literary treatment of anger appears in Dante’s Inferno, where it occupies the fifth circle of hell, ranking in severity between greed and heresy. Anger shares this circle with sullenness because they are two forms of the same sin: expressed anger is wrath; repressed anger is sullenness. Dante writes that the wrathful attack one another while the sullen stew below the surface, both confined to the muddy swamp Styx (7.109-26) for eternity.

There is an eerie chaos to the world today, a palpable feeling that we have become unmoored from the basic moral ideals that once bound us together. We are not, it seems, so unlike the enraged souls in Styx condemned to torture each other until they are both devoured. That was hell, literally. But, in many respects, it’s where we find ourselves today.

The thing about hell (or one of the things about it) is that it is a place of brokenness and separation; broken souls separated from life, from God, and from each other. What happened to us during the pandemic bears an eerie resemblance to this place; it separated us in ways we couldn’t imagine and created its own personal hell for so many who found themselves jobless, unfriended, broke, or disenchanted with others and with life.

Anger can be destructive, no doubt. And sometimes its destruction is perfect and permanent. But the realist in me thinks that, whatever its disvalue, our anger isn’t going anywhere anytime soon and we would do well to figure out how to channel it into something useful. To understand what this might look like, I want to begin by looking at how anger is related to other moral virtues, courage in particular, to see whether it is always destructive, or sometimes useful and justified.

Fuel for Our Courage

Angry people today are often portrayed as cowards. They are chastised for not letting things go, for not growing up, for refusing to comply and make the needed sacrifices during a crisis. But while anger can sometimes be a way to dodge other, more difficult-to-process emotions, research suggests that it can also be a catalyst for some of the moral virtues, courage in particular.

In a 2022 behavioural study, researchers explored the connection between anger and moral courage. While participants were supposedly waiting for the study to start, they overheard two experimenters plan, and then, execute the embezzlement of money from the project fund. (The embezzlement was staged.) The participants had various opportunities to intervene, including directly confronting the experimenters, involving a fellow participant, or reporting to a superior. Depending on your perspective of the events of the last few years, you may or may not be surprised to learn that only 27% of participants intervened. (Other experiments, including the Milgram experiment, confirm the natural human inclination towards passivity). Interestingly, researchers found that the more an individual reported feeling angry, the more likely they were to intervene, showing that anger can serve as an important catalyst for moral courage.

There were a lot of reasons to be angry over the last three years. The vaccinated were angry at the unvaccinated for what they saw as irresponsible behaviour. The unvaccinated were angry at those who fuelled what they took to be a misleading narrative. Even now, complicity and inauthentic forms of redress — gaslit justifications, weak contrition, and empty apologies — are ubiquitous. Those asking for “COVID Amnesty,” a Prime Minister claiming he never forced anyone to get vaccinated, the friends who shut us out, and of course Anthony Fauci denying in 2022 that he recommended “shutting everything down” (even though he said in an interview in October 2020 that he told President Trump to “shut the country down”). The list goes on and on.

Shouldn’t these things enrage us? Shouldn’t they leave us with exactly the same reasons to remain angry that we had to get angry in the first place? And wouldn’t it actually be cowardly to abandon your anger just because others expect it or because you expected it eventually to give way to tamer emotions?

Though it might be hard to reconcile the idea of morally pure anger with a picture of the virtuous person as rational and even-keeled, being good doesn’t necessarily mean being indifferent. Sometimes anger is justified, and sometimes it is exactly what injustice demands. Having a “good temper” doesn’t mean being apathetic; it means we need to ensure that our anger is dispensed appropriately. And I think we need to consider that it may only be anger’s intensity, its incandescence, that can do certain kinds of moral work, energizing us to fix what cool-headed indignation cannot.

A Caveat

However we try to justify it, anger is a dicey business. And we have long known it. There are thirteen different words for “anger” in Homer, one of them being the special subject of the Iliad, a cautionary tale about characters so angry they crossed the Trojan plain to slaughter one another. The Greeks and Romans knew that anger can be a social poison, an anathema to healthy public life, making us say and do things that can’t be undone. I’m sure you can easily think of examples in your own life in which rage and vindictiveness operated like a positive feedback system, feeding the beasts that create them.

And it’s important to remember that anger can destroy not only its perpetrators but its victims as well. Being slighted, stigmatized, and oppressed — some of the common effects of anger — can create enduring moral wounds. It can make you bitter, envious, and myopic about the role you played in creating your own circumstances, and unconfident about the effectiveness of standing up for yourself. It makes you tired in your soul, nurturing a ‘why-bother,’ self-affirming attitude. Just because anger is sometimes justified doesn’t mean there aren’t deep moral costs.

It’s also important to remember that, useful though it may be, anger is a finite resource. It is reactionary and naturally wanes over time. Intense anger cannot be maintained indefinitely if only because we don’t possess an infinite resource of the hormones and neurotransmitters that support it (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol, to name a few). The intensity of these emotions makes you battle-weary and “burned-out,” the signs of a body exhausted of the chemicals needed to support those emotions. Rage is exhausting, possible to sustain for a time maybe, but hard to rely on as a long-term motivator and harder still to keep confined to one area of your life.

I sometimes worry that the rage I allow to fuel the public work I do will seep into the private areas of life where it could undermine the softness I need to be a good friend, spouse, and mother. How careful we need to be not to let the anger we harness for important moral work turn us into angry people, more generally.

It’s Personal

So what is the real injury we have done to each other with our anger?

One thing I think that the angered and the victims of anger can agree on is that the pain and destruction our anger causes is deeply personal. Anger is a kind of moral looking past or looking over. As Nussbaum says, anger is a voluntary failure to take another seriously, treating them as having so little worth that they don’t even deserve acknowledgement. Our cancel culture, which not only tolerates but celebrates cancellation, takes this to the extreme. Managing our disagreements by excising and silencing others, thinking of ourselves as so morally superior that our indignation is justified, ultimately dehumanizes us all.

Isn’t this the essence of the pain felt by being the victims of anger today? It’s not the particular things others say or do to us, but the feeling that we are being dismissed, that we aren’t seen as persons with unique histories and feelings and reasons for what we believe. The default reaction first to reference fact-checks in conversations with loved ones, as opposed to asking questions and listening for answers, shows that we are routinely guilty of overlooking, and devaluing, the people in our lives.

But all is not lost. There is a positive side to the deeply personal aspect of anger. The intensity of our anger, and the personal ways in which we feel it, shows that we are deeply social beings, and that the more angry we get, the more we feel something valuable slipping away. It shows us just how perilous social life can be, and that we are not wholly self-sufficient, capable of fully flourishing without one another. Relying on others is a risky business, leaving us sometimes wondering if it’s a risk worth taking. And it makes plain the harrowing truth that being seriously wounded in our most intimate relationships is always a possibility.

It’s natural to experience these wounds as a deep loss. The loss of being loved and cared for, yes, but also the loss of being someone who loves, who cares for others, and who can experience the choreography of a shared life. When it comes to couples whose relationships didn’t survive COVID, they didn’t just suffer the loss of a partner but loss of who they were in a partnership.

Payback is especially attractive when one suffers in these ways because retribution feels like a satisfying way of returning in kind the deeply personal ways we were wounded. It is tempting to focus on the past where we understood who we were, and where our contributions felt valuable. That can be much easier than recreating ourselves for an uncertain future. And so it is tempting to make others suffer in the present for what they did in the past.

But there is a problem with using anger to try to correct the past in this way: the past, however vibrant and painful its events can feel in the moment, cannot be changed. And trying to change it is a fool’s errand. The past is set. There are no resources there to satisfy our need for justice. Retribution bypasses what we really need when we are angry: an acknowledgement that we have been wronged, and a recognition that the other’s words and actions caused pain; they had a victim.

This is why people — whether it be politicians or loved ones — asking for amnesty is so painful; because it bypasses the acknowledgement that we were hurt in the deepest ways possible. What victims of injustice need is not retribution but acknowledgement and the recovery of what never should have been lost.

But what do you do when what was lost is irrecoverable, a reputation or a child’s life? What do you do when you know there will never be an apology? We must find a way to move on even without it. If we dwell on the loss, there’s no healing and no moving forward.

A wise friend recently reminded me that wrongdoing that happens to us is often not about us. As she elegantly said, “the wounds people inflict can come flying out through the violent vortex of their own dysfunction and hit us like shrapnel.” And so our wounds become the byproduct of their wounds. I’m not sure this lessens the intensity of the wound, itself, but realizing that the injury is not as personal as it might have been helps us to move forward. We can feel sorry for the broken and terrified person our perpetrators are while at the same time carefully holding the memory of the wrong they did to us in our pocket as a reminder and a warning.

Sometimes there is no possibility of acknowledgement, no hope for apology. And sometimes forgiveness is a tall order. The only way forward might be to honour our injury by remembering the harm while letting go of the idea that those who harmed us will be part of the story of our healing.

In Search of a Cure

If Seneca was right that anger is madness in need of a cure, what could cure us of the pandemic of rage we find ourselves in today? How do we isolate and develop the morally pure and purposeful form of anger, and purge the more destructive forms? How do we catalyze the wanton anger that consumed us during COVID into something that has a hope of addressing the problems that put us there?

As it often does, history offers some suggestions, some more promising than others. Before he became emperor, Augustus was tutored by the Stoic Athenodorus Cananites who offered him the following advice, “Whenever you get angry, Caesar, do not say or do anything before repeating to yourself the twenty-four letters of the alphabet.”

The idea that reciting our ABCs will quell our 21st-century rage is a bit laughable but perhaps we have our own versions of Athenodorus’ advice that are equally ineffective. Nasty Tweets, honking at a stranger in the parking lot and other micro-outbursts of aggression might feel like satisfying releases of pent-up frustration. Doom-scrolling and binge-shopping might feel like apt antidotes for our rage. But neither address the true cause of our anger.

So what could cure us?

The ego isn’t a bad place to start. I said earlier that Nussbaum relates anger to ego, describing it as a natural response to social downgrading, or to the loss of reputation or power. Decades of research confirm her suggestion. It shows that we tend to rate ourselves more highly compared to others on a variety of positive measures, including intelligence, ambition, and friendliness (a finding referred to as the “self-enhancement effect”) but that we do so most profoundly when it comes to moral attributes; we typically believe that we are more just and honest, and generally more virtuous than other people. We tend to believe the best about ourselves and the worst about others; the injustice can’t be my doing as I am clearly the more aware, socially conscious person. So it wouldn’t be surprising if Nussbaum is right that anger is rooted in egocentricity.

Anger that is rooted in the ego is personal in nature and more likely to be looking for a scapegoat to appease its pain and suffering. Ramming the shopping cart into a fellow shopper’s heels feels good. Or it seems to. Your anger, at least gets a point by making someone else hurt.

The morally pure form of anger, on the other hand, seeks true justice. It saves its energy not for revenge but for peace. And it knows that taking others down, even enemies, only compounds the injury of an already injured world. Ego-based anger is short-sighted and destructive. Righteous anger, on the other hand, turns a cheek, but keeps its eyes open in the process. It plays the long game, moving forward with clarity and calculation, rather than selling out to cheap and momentary revenge.

There are a lot of reasons not to embrace victimhood. Dwelling too long on the idea that we are victims makes the story about us. It gives our ego power. Remember the point above about perpetrator harms being more about the perpetrator than the victim. If you remove yourself as the subject of the story, it’s easier to realize that the harm wasn’t personal. And there’s something about that which dampens the pain a little.

Our egos have been profoundly affected over the last three years. Being unable to work, travel, or consent, and being disrespected, silenced, and shut out are pretty extreme forms of social downgrading. It’s not at all surprising, or unreasonable, that they would anger us.

But we need to be careful with ego. Even if it is sometimes a useful defence against being downgraded, self-righteousness can be destructive because it intensifies the distance between ourselves and others, reduces our willingness to cooperate and compromise, and can lead to intolerance or even violence.

No new information here. We know from Sophocles what happens to those whose egos run amok (think of the consequences of Oedipus’ excessive pride and Creon’s stubbornness). This is at least in part why the tragedians crafted theatric opportunities for catharsis, a kind of moral exorcism to purge ourselves of destructive emotions just as we might cleanse ourselves of a physical toxin.

Are we in need of a moral catharsis today? If so, what would this look like? What could we do to identify and purge ourselves of our pent-up anger and amorphous frustration?

Unfortunately, true catharsis isn’t easy to come by. It certainly isn’t achieved by snide comments, angry tweets, and other acts of passive aggression, as effective as these sometimes feel. And catharsis isn’t just a matter of releasing anger. It requires confronting the flaws that caused us to make the choices that ultimately led to our tragic destruction. True catharsis requires self-awareness and self-knowledge, and creating those can be the hardest, most painful work of all.

But isn’t this exactly what we need today? We need to look our mistakes in the face, and acknowledge our role in the suffering of ourselves and others. We need to come face-to-face with the harm done even by our acts of compliance and acquiescence that, at the time, seemed so harmless. We need to atone for our willful blindness and turning our backs on the people and causes that needed us most. And we need to confront the consequences of the vacant defence, “I was just following orders.” True catharsis requires much soul-searching and atonement, and I worry that this might be too much to expect at a time when introspection is so unfashionable.

Grief Conversions

Being pure in purpose doesn’t mean anger will always be pure in experience. And just because anger can be productive doesn’t mean it can correct for all past wrongs. Some parts of our broken world are beyond repair: the child who dies because of bad government policy, the social stunting from unnecessary lockdowns, time and opportunities lost, and systemic mistrust built up over years of gaslighting and betrayal.

The moral work required to stand up for what one believes in has left many feeling burnt out, lonely, and unsure of how to carry on. The rationally angered might feel foolish that their initial hope was misplaced, or they might grieve the loss of what they might have been in a more just world. I sometimes feel resentful that a more peaceful and innocent life has been stolen from us. And I resent the fact that it is those who have caused the most harm, who have the ‘dirtiest hands,’ who are the least likely to do this work.

So, what do we do with our feelings about the injustices that can’t be fixed? What does virtue allow us to do, require us to do, next?

The typical, and some say appropriate, emotional response to facts that are regrettable but unchangeable is grief. Grief at the loss of what was, of who one was, or of what might have been. And so perhaps it isn’t surprising that the words for “anger” and “grief” share a common origin (the Old Norse root of anger, “angr,” means “to grieve or distress,” and “Angrboda,” a supernatural being in Norse mythology, means “The one who brings grief”).

If Callard is right, that “there are not only reasons to get angry but reasons to remain angry, and they are exactly the same reasons we had for getting angry in the first place,” then anger can be a way to transform our grief into something productive. As MacBeth’s Malcolm suggests, “Let grief convert to anger; blunt not the heart, enrage it.”

But not all injustices can be fixed by getting up on our white horse and riding out into our broken world to fix them. Morally pure anger, as productive as it can be, can create a false promise of agency in a world that offers increasingly less control over every facet of life. When anger has no productive outlet, when past wrongs cannot be fixed, then anger may have nothing left to do but convert to grief. And we can grieve and honour our losses as peacefully and reverently in measure with what they deserve.

Let’s end by returning to Callard’s question: Should we stay angry forever?

Possibly. But, unlike those who joyously settle into their contempt, the rationally angered won’t celebrate others’ hardships. They won’t cancel, berate, mock or shame, and they certainly won’t dance on graves.

But they also won’t forget.

To be clear, I am not advocating for wanton terrorism, burning down buildings, or shutting down cities to bring attention to injustice. Even morally pure anger doesn’t justify frivolous destruction. But as long as we are clear about what should come ‘out’ of our anger, it can be an ethical weapon as precise as a surgical scalpel.

Also, the reality of our world is that slow, incremental change to a broken system is not always enough. The fractured institutions of today — health care, government, media, education — demand wholesale change. When we are told that only certain ways of living are valid, and only certain people matter, namely those who follow a particular narrative and endorse a broken system, it is time to rebuild that system. Major societal change often comes about only when attempts at gentle correction toward a more reasonable course have proven futile. Rosa Parks sat down on the bus after two centuries of failed attempts to fight segregation.

Sometimes the realities of our world stretch our humanity too far. The prevalence of pent-up frustration today might be a testament to the gap we perceive between where we are and where we might have been. If so, we need to see that for what it is. We need to take up the gauntlet, and prune our anger into something that has a chance of repairing our moral injury so we are better equipped for the future.

Please don’t think that, to be good, you need to be quiet and agreeable and complacent. And please don’t think that any of this will be easy. But it will be preferable to the personal destruction and social division created by festering, unacknowledged anger. To that end, let me leave you with the words of the classicist William Arrowsmith who writes, in his commentary on Hecuba, about resisting madness in the face the world’s injustice:

Man continues to demand justice and an order with which he can live…and without the visibility of such order and justice, he forfeits his humanity, destroyed by the hideous gap between his illusion and the intolerable reality.

Indeed.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.