I remember my history textbooks explaining the use of cartoonish figures as propaganda during the two World Wars. Imagine, for a moment, the inspiring Rosie the Riveter and Uncle Sam contrasted against the overbearing, dull, and cartoonish displays of the fascists and communists.

I was inspired by Rosie, and at the same time, I viewed the cartoons of our enemies out of context and wondered, How could anyone be influenced by cartoonish, pastiche, caricatures?

Today, the information war of cartoonish potpourri completely overwhelms us. We are awash with memes, short-form video content, tweets, posts, reposts, likes, etc. We have all viewed this content, and when it inspires some emotional response — joy, laughter, anger, indignation, surprise — we forward it onto the next person. Virality is now an everyday feature of life.

Virality with this ease of spread is a fairly novel psychic phenomenon for the human race. So, when a novel physical pathogen came along, both the disease and the memes, cartoons, and propaganda began to spread. Confronted on both physical and psychic fronts, some incredibly bizarre and often vindictive behavior resulted. It isn’t the first time this has happened.

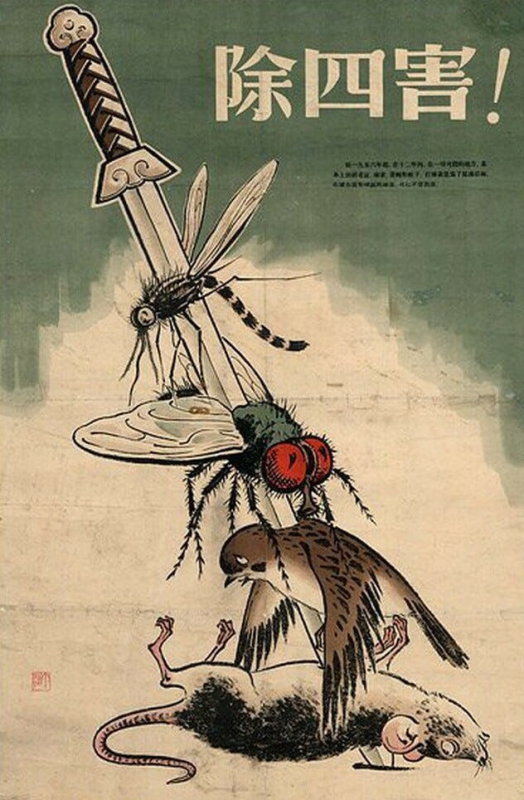

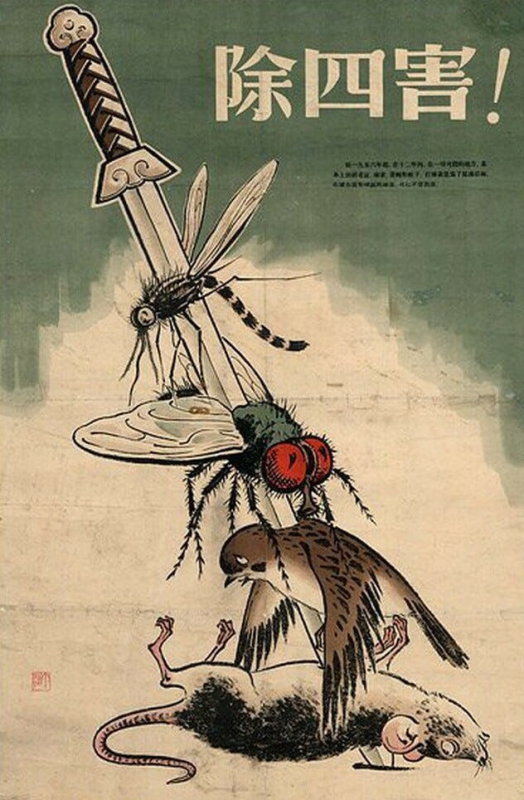

In China, after the communist revolution, farming was collectivized. Newly mandated agricultural practices were disruptive, and food production began to falter. One of the new mandates during the Great Leap Forward was the commencement of the Four Pests Campaign.

Rather than go back to what had worked before, or allow markets to work, the authorities settled on a seemingly sensible solution. Rats, mosquitos, flies, and sparrows — yes, the small bird — would be eliminated. With these pests eradicated, the models projected food production would exceed all of the previous levels in every metric.

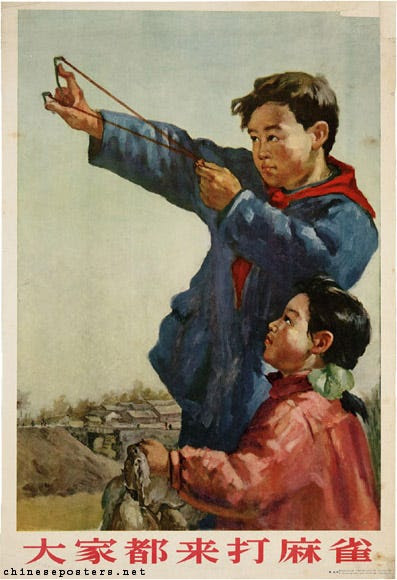

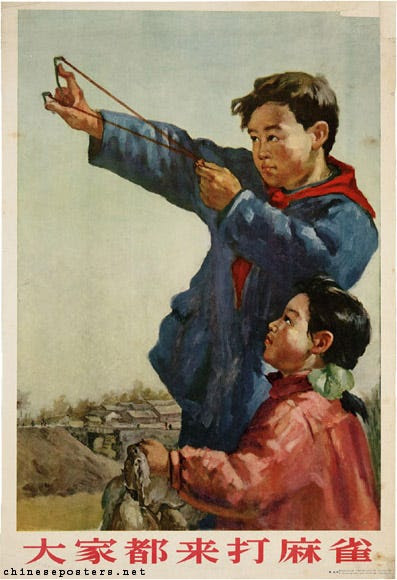

Slaughtering birds isn’t exactly something that comes naturally though, so the populations had to be informed. Cartoons and memes were created:

This propaganda campaign targeted children in particular, and it was popular. After school, the children would set up ladders to destroy sparrow nests, and in the evening — when the sparrows would return to the roost — they would bang pots and pans. This scared the birds and kept them in flight until they died from exhaustion and fell out of the air. It was not only fun, but they were heroically stopping the spread of disease and conquering nature in support of their nation.

The campaign against the sparrows was quite effective. The old Daoist philosophy of harmony with nature was abandoned, and the sparrow population was utterly decimated. The dissonant harmonies were ignored. Mankind would usurp nature; displace it and rule in its stead.

Dissonant harmonies, however, call to be resolved, and in this case, the sudden disappearance of the sparrows resulted in ecological disaster. Sparrows did eat the seeds needed for planting, but they also ate insects that fed on the crops — in particular, locusts. Lacking a predator to control their population, the number of locusts boomed. They swarmed and ate everything they could find. Combined with a drought, the Great Chinese Famine was the result. Estimates are that between 15 and 55 million souls died from starvation during this era.

Today, we view these cartoons from the abundance of our own homes, and believe that if we were in China during this time, we would not have conducted ourselves in such a silly manner. Banging pots and pans to scare birds to death?

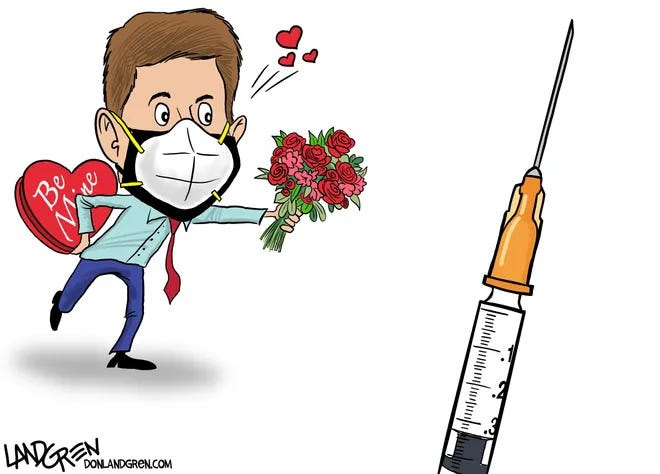

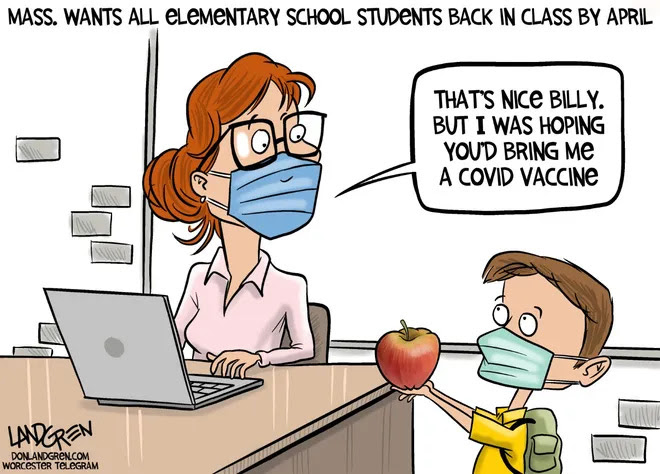

Our cartoons, context, and narratives are different, but the psychic phenomenon remains the same. Wearing a mask, social distancing, closing school, and shuttering businesses doesn’t exactly come naturally, so the population must be informed.

We required transformation of every aspect of normal life. The cartoons and news stories tell the tale. The metamorphosis denatured Valentine’s Day, Life’s Badges of Honor, “Official” State Stones, and the schooling experience. We banged pots and pans in support of the valiant effort.

Then, there are the officially scientific cartoons. An actual computer model used for risk management — the Swiss Cheese Model — was applied to Covid-19. An illustration of the concept is below; published in cartoon form in New Zealand, and also the Cleveland Clinic, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal, among others:

Cartoons are an important tool for our government agencies. The CDC produces Social Media Toolkits for various different purposes. Many of the images from the toolkits are often cartoonish in nature. Here is one of several images directly from the CDC’s website related to masking:

Cartoons are simply the most shareable method of propaganda. They require minimal investment of attention, but they inspire a rapid emotional response. The cartoons are useless by themselves, but when presented within the context of a larger narrative, they quickly either confirm a passing, enthusiastic support for the cause or an ephemeral disgust.

Men (people) are rarely aware of the real reasons which motivate their actions.

In place of thoughts [the group mind] has impulses, habits, and emotions.

Edward L. Bernays, Propaganda

Thus, if a person went all in on Covid protocols, each additional layer of protection they practiced was simply another slice of Swiss cheese. This is a completely sensible application of the Swiss cheese model, and if the model was correct, it would have been an effective solution.

However, the pandemic policies were failures the world over. The unintended and unforeseen consequences will continue to be discovered for years.

In China, a critical point was enthusiastically approached for years by the population. When it finally arrived, the result was unfathomable famine.

Today, there is a veil of silence over still elevated levels of excess death, lockdown-related deaths and deaths of despair have skyrocketed, and we won’t understand the full effects of closing schools for a decade or more at the earliest. Unbelievably, we retain the risk of doing it all over again.

In a world where mask-required signs were hung on every entrance-way, stickers indicated safe places on the floor, and an employee wiped the handle of every shopping cart with a filthy cloth, it is a mistake to think we are immune to the effects of propaganda. We must ask: how can we ensure our protection from it?

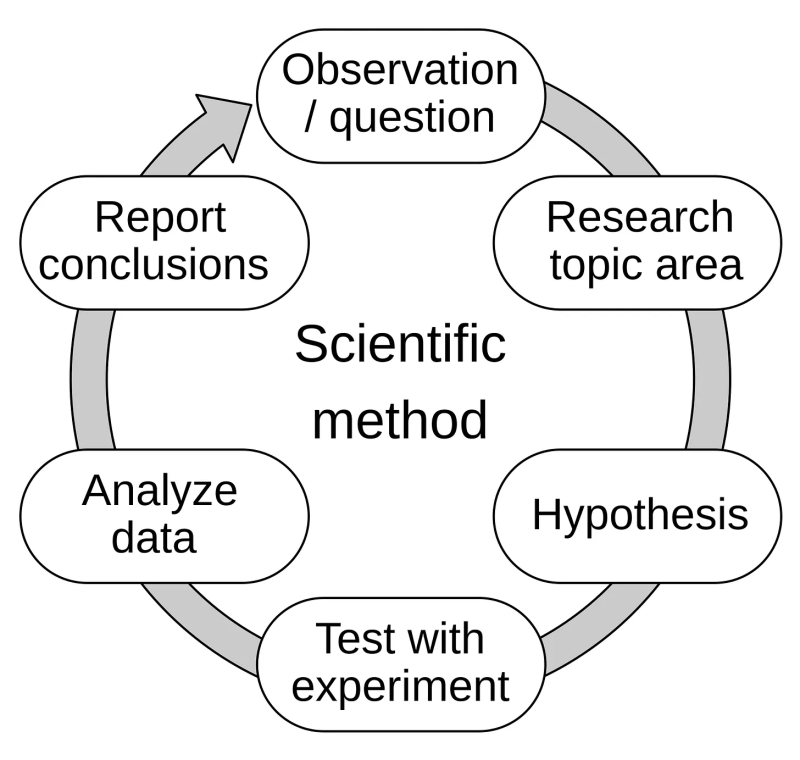

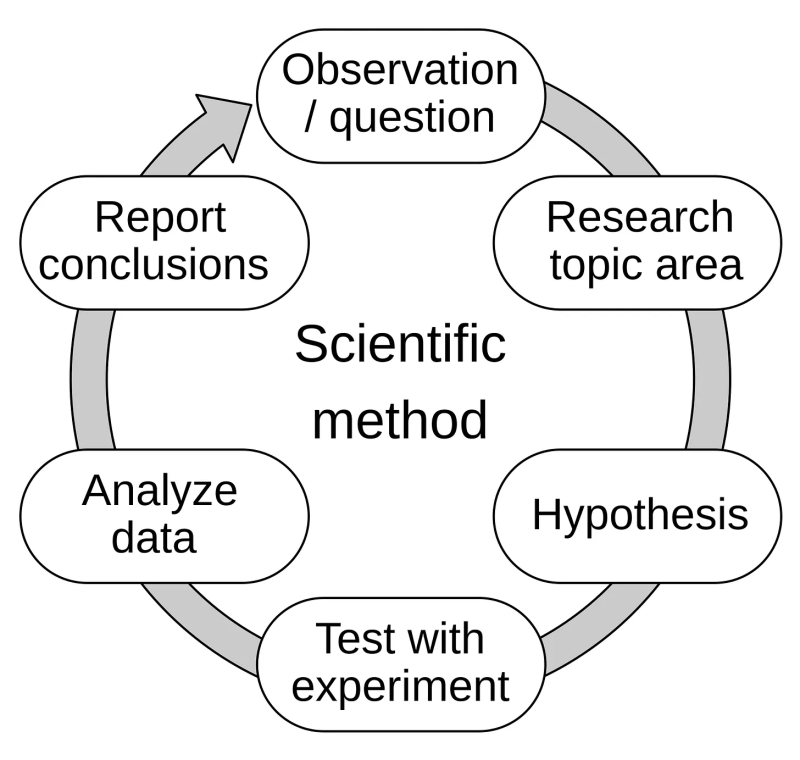

We start with questions. Am I being asked to behave in a different way than I did yesterday? If it’s a special circumstance, have these behaviors ever been applied before? What effect, if any, did they have? If they were effective, are the conditions similar such that the results can be repeated? Are the results being repeated or has any novel intervention had a measurable effect?

One might recognize this process as the Scientific Method, presented below as a cartoon:

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.