Enter “Covid” plus “selfish” in a Google search box and you’ll get over 28 million hits. Here’s the type of headline that pops up:

- “Don’t be one of the selfish idiots putting us all at risk” (Edinburgh News, Sept. 24, 2020)

- “Too many Americans are selfish, and it’s killing people” (Los Angeles Times, Jan. 1, 2021)

- “As long as selfishness wins, the pandemic is here to stay (Orlando Weekly, Jan. 12, 2022)

- “Selfish, stupid COVID protesters get short shrift in Wellington” (Aljazeera, Feb. 14, 2022)

Since the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, people have slapped the “selfish” label on those who didn’t share their zeal for lockdowns and restrictions. Remember the “disgusting display of selfish behavior” in Missouri’s Lake of the Ozarks on May 24, 2020? The “selfish and dangerous” people who flocked to Trinity Bellwoods park in Toronto that same day? The “selfish and irresponsible” beach goers in the UK town of Bournemouth two months later?

The word “selfish” rose to new heights as the global vaccination campaign ramped up throughout 2021. In July, UK Cabinet Minister Michael Gove threatened to bar the “selfish vaccine refusers” from events, and five months later a Canadian radio personality exhorted the unvaxxed to “stop being a scientifically ignorant, selfish drag on society.” In April 2022, the word gathered fresh steam when a judge struck down the transportation mask mandate in the US. A Washington Post article described plane travelers’ reaction to the mid-air announcement as “whoops of selfish delight,” while the Boston Globe decried the jubilation as the “unmasking of a selfish nation.”

Even those who do wear masks may face a charge of selfishness—if the mask is the wrong kind. When advising the public against the use of valve masks, Yuen Kwok-yung, a microbiologist and professor at the University of Hong Kong, described them as “a bit selfish. In other words, they filter what a person breathes in, but when you breathe out through this valve, it doesn’t filter well.”

All in it together?

Caught in the froth of their moral indignation, the finger pointers never doubt that they hold the correct, “unselfish” world view. They don’t consider that the pandemic strategy they endorse, which requires everyone to dance in lockstep around a single threat, may cause downstream suffering to a large swath of the human family—like the estimated 50 million extra people plunged into extreme poverty by 2030. They dismiss the mental-health impact of social isolation and business closures as a “necessary sacrifice,” pooh-pooh the ethical arguments for bodily autonomy, and reduce the profound ramifications of canceling the human face to “just a piece of cloth.”

This is not to say that people can’t or shouldn’t band together to solve a problem. But collective action only works when it springs from the ground up. People can’t really “band together” when forced to do it. It’s like telling someone to surprise you on your birthday: the very request negates its fulfillment. Andreas Kluth, author of Hannibal and Me, a book about how political figures respond to disaster, nailed the conundrum in a 2021 Bloomberg article: “Collectivist ‘solidarity’ is thus neither totally voluntary nor inclusive, and ‘harmony’ tends to be coerced and parochial.”

And here’s a dirty little secret: individualistic cultures turn out more unselfish people than their collectivist counterparts, as discovered in a 2021 psychocultural study of the world. “We found that in more individualist countries like the Netherlands, Bhutan and the United States, people were more altruistic across our seven indicators than were people in more collectivist cultures,” says Georgetown University psychology professor Abigail Marsh, one of four researchers who conducted the study.

On a more fundamental level, collectivism suffers from the fallacy of misplaced concreteness—treating abstractions like “society” or the “common good” as concrete entities that exist in the real world. As Carl Jung points out, “Society is nothing more than a term, a concept for the symbiosis of a group of human beings. A concept is not a carrier of life.”

The only way to achieve a grounded and democratic “common good” is to give flesh-and-blood individuals the freedom to define it and pursue it. John Stuart Mill says it best: “The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs or impede their efforts to obtain it. Each is the proper guardian of his own health, whether bodily or mental and spiritual.”

Selfishness reconsidered

No doubt some people would brand Mill’s position as a selfish one—the same people who view a planet-wide commitment to stamping out Covid as the obviously unselfish choice. To Vinay Prasad, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California San Francisco, it was never that simple. The Covid Zero champions—the group that believes that any restriction is a good restriction—“routinely and falsely claim that their policies protect minorities and low income people, when those policies do the precise opposite: protect the rich and transfer wealth upward,” he writes. “Never content with merely sheltering themselves, they wish to use brute force to compel others to do things that they think helps them, even if there is no data supporting those things.”

Which is more selfish, demanding that everyone follow the same rules in perpetuity—rules that feel comfortable to the most risk-averse among us—or giving people the freedom to assess and manage risk as they see fit? Which is more selfish, dictating the minutiae of people’s lives in a chaotic effort to “slow the spread” or treating them like adults who can make adult decisions?

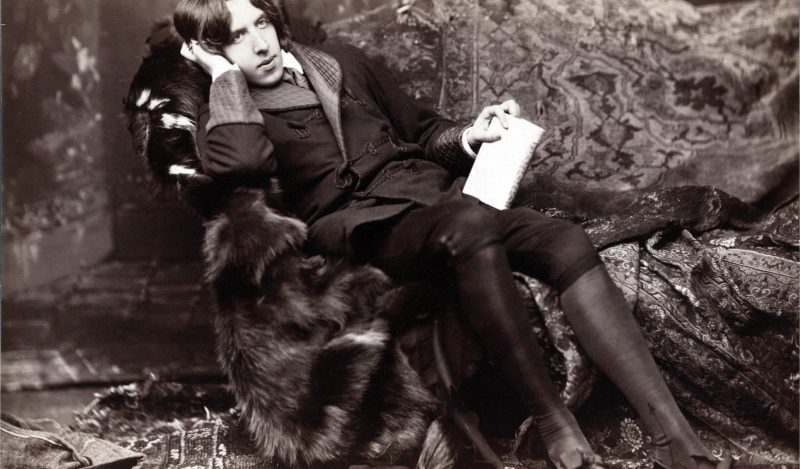

I stand with Oscar Wilde here: “Selfishness is not living as one wishes to live, it is asking others to live as one wishes to live,” he famously stated. “And unselfishness is letting other people’s lives alone.”

Aaron Schorr, a Yale University student on immune-suppressing medication, would likely agree. “I didn’t expect the government to structure its entire [Covid-19] response around my personal well-being,” he wrote in the January 2022 issue of Yale News. “Feeling unsafe? By all means take extra precautions, but 4,664 undergraduates should not be forced to adhere to the same standard.” If anyone merits the “unselfish” prize, it’s Schorr—not the campus activists calling for mandates until the end of time.

Reality-based policies

More than two years into the pandemic, public health experts, politicians and ordinary citizens continue to blame policy failures on human selfishness, rather than on the policies themselves. It’s like blaming a failed math-education method on the students’ stupidity. The students are what they are. Should we rage at them for their lack of aptitude or revisit the method?

As the saying goes, we fight a war with the army we have, not with the army we wish we had. If humans are indeed selfish (however we define the word)—well, that’s our army. America’s Founders, to their credit, understood this from the get-go. As noted by Christopher Beem, Managing Director of the McCourtney Institute of Democracy, “they accepted the reality of human selfishness and developed institutions—especially the checks and balances among the three branches of government—whereby people’s natural selfishness could be directed toward socially useful ends.”

Pandemic policymakers would do well to remember this. Policies that ignore people’s natures and self-interest will backfire sooner or later. Kids need to run around, teens to connect, young adults to explore. Older people need these things, too. For a limited time, people can set their basic needs aside. But asking humans to stop acting like humans until some ill-defined and ever-receding endpoint? Not everyone will sign up for that, and you can’t blame those who opt out.

My Zoom shrink understood this. (I talked to him every few weeks during the first year of Covid, almost exclusively to dissect the societal response to the virus.) “These were young urbanites who lacked green spaces,” he said of the revelers at Trinity Bellwoods park. “After two months of lockdown, they did what young people are programmed to do on a gorgeous spring day: get together.”

We need pandemic policies rooted in human nature—policies that meet people where they are, not where some sanctimonious Twitter warriors decide they should be. Throwing the S-word around doesn’t earn respect or cooperation from the accused. Au contraire: when pelted with character-assassinating epithets, people double down.

For the remainder of this pandemic and for the next one, I’ll leave public health experts and policymakers with these considerations: Stop calling people selfish for wanting some agency and quality in their lives. Stop bullying them into “caring” about a vulnerable stranger who lives three states or continents away.

Instead, tap into their natural motivation to protect themselves and their loved ones. Communicate risks transparently, provide strategies to reduce them, and treat humans as humans—the way you used to manage pandemics before Covid.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.